On the face of it, the protests, court filings and the stand-off between activists and authorities over the Dakota Access Pipeline pits those who want to boost energy production against those who want to protect water resources around the Missouri River. At a deeper level, however, the controversy over the DAPL is part of a much larger and older fight over the idea of Indian nationhood. This month David Nichols traces the history of Native sovereignty and the struggle to make the United States honor the obligations of treaties it has signed with Native nations.

Since April 2016, members of the Great Sioux Nation have been protesting, through nonviolent direct action, the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). The 1,900-kilometer pipeline runs from the Bakken oil-shale region in western North Dakota to a tank complex in Illinois.

Its route crosses the Missouri River directly adjacent to and upstream of the Standing Rock Reservation, one of several belonging to the Dakota and Lakota Sioux. A pipeline break would directly threaten the principal water source of not only Standing Rock, but more than 15 million other people.

The Sioux do not stand alone in their opposition to the DAPL. The project has also drawn objections from conservationists, white farmers, and the Meskwaki (Fox) Nation of Iowa. Theirs has nonetheless become the most dramatic demonstration against the project, drawing international attention and support.

Thousands of “water protectors,” representing 300 Native American nations and their allies, have gathered near the Cannonball River, and many have attempted to block construction of the pipeline. Their actions led to clashes between protesters and security and police officers armed with water cannons, tear gas, and armored vehicles.

To the historically minded, the anti-DAPL protests and their armed suppression recall the Civil Rights demonstrations of the 1960s, and the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Wounded Knee, S.D. in 1973.

Protesters and police faced off in Standing Rock in October 2016.

The NODAPL protesters seek to protect land and water, and also to remind other Americans of their treaty obligations to Native Americans. To do so, they draw on much older legal and cultural precedents. The demonstrators named one of their encampments the “1851 Camp,” and in justifying their decision to block pipeline construction declared that the right-of-way belonged to the Great Sioux Nation under the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Other indigenous-rights activists observe that a subsequent agreement, the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, guaranteed the Sioux “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of their reservations unmolested, which necessarily includes the right to an “undisturbed,” uncontaminated water supply.

Indian treaties might seem antique documents to modern mainstream Americans, who probably think of them as agreements that their white ancestors made only to break. Legally and politically, however, treaties remain valid compacts.

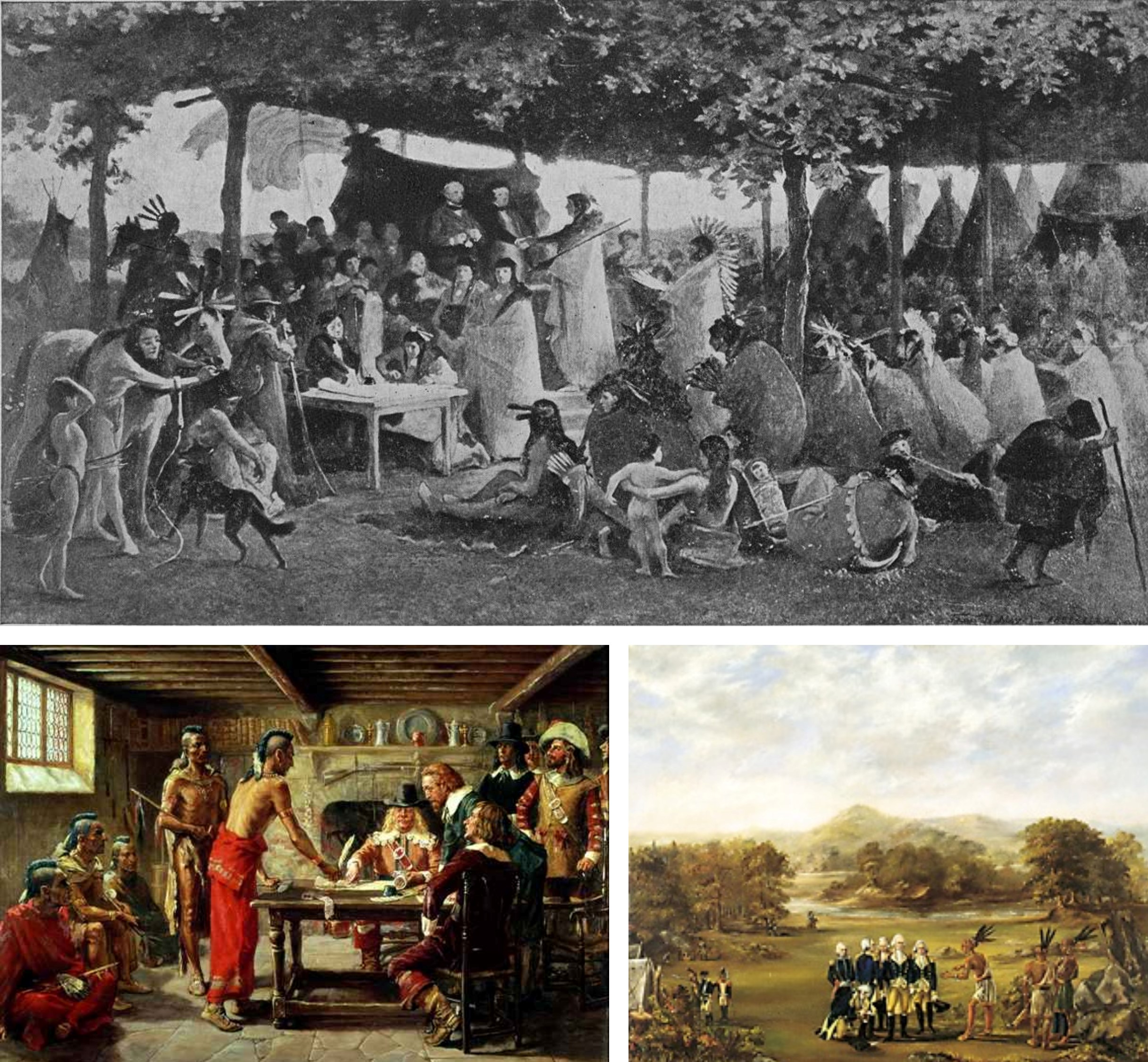

The signing of a treaty in 1851 between the U.S. and the Sioux Indian bands (top). Signing of a peace treaty in 1642 in New Amsterdam (present-day Manhattan) between the Dutch and Lenape Indians (bottom left). The United States and a coalition of Native American tribes, known as the Western Confederacy, signing the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 after the latter’s defeat in battle a year earlier (bottom right).

The U.S. Constitution specifically grants the federal government the power to negotiate treaties with Indian nations, and regards those treaties as part of “the supreme law of the land.” The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1905 (United States vs. Winans) that Indian treaties remain valid, and constitute “grants of rights from” Indians to the United States, not the other way around.

And to Native Americans, treaties are very much living documents. Congressman Tom Cole (R-OK and a member of the Chickasaw tribe) reminds his colleagues and constituents that treaties recognize tribal rights that existed well before the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. These are rights that grew out of Native Americans’ pre-Revolutionary status as sovereign nations, which the U.S. government repeatedly agreed to respect—nearly 400 times between 1778 and 1871, in fact.

The goal of the NODAPL movement is not merely to stop construction of a potentially dangerous pipeline, but to spotlight the obligations of the United States to the sovereign Great Sioux Nation: to respect their lands and not foul their water.

The encampments and protests at Standing Rock serve still another purpose: to demonstrate the organic continuity of Sioux nationhood. They are ceremonies of sovereignty.

A November 2016 march in San Francisco in solidarity with Standing Rock protesters.

Sovereignty is Born

Sovereignty can seem an opaque concept, but once we look closely at its origin we can see that Indian treaties either acknowledged, refined, or granted terms that collectively ascribed sovereignty to Indian nations.

In international law, sovereignty first emerged as the defining feature of nation-states under the “Westphalian system” created by the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, Germany. Before 1648, European states theoretically had to share authority with supra-national institutions like the Catholic Church. After Westphalia, sovereign nations became much more independent of one another, particularly in their internal affairs (such as law enforcement).

In early-modern Europeans’ eyes, a sovereign nation need brook no interference with its internal governance. A nation-state might claim to receive its sovereignty from God, but as a matter of law this came from other sovereigns’ recognition of its independence—from their admission of that nation-state to their own exclusive club.

The nationalist revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (including the American one) and the World Wars of the twentieth complicated the picture. Sovereignty increasingly became associated in political leaders’ minds with the right of particular peoples to self-government. The 1933 Montevideo conference and the 1945 Charter of the United Nations drew together old and new understandings of sovereignty to propose a broader definition.

In the view of twentieth-century diplomats and political leaders, a sovereign nation-state had defined territorial boundaries, a defined national population, a set of national resources, and diplomatic recognition by other sovereign nations.

Treaties with the United States affirmed Native Americans’ possession of these sovereign attributes. Most American Indian treaties defined Indians’ territorial boundaries because most involved the sale or transfer or land. From 1790 to 1870 Native peoples, either voluntarily or through coercion, ceded through treaties between 500 million and 1 billion acres of land.

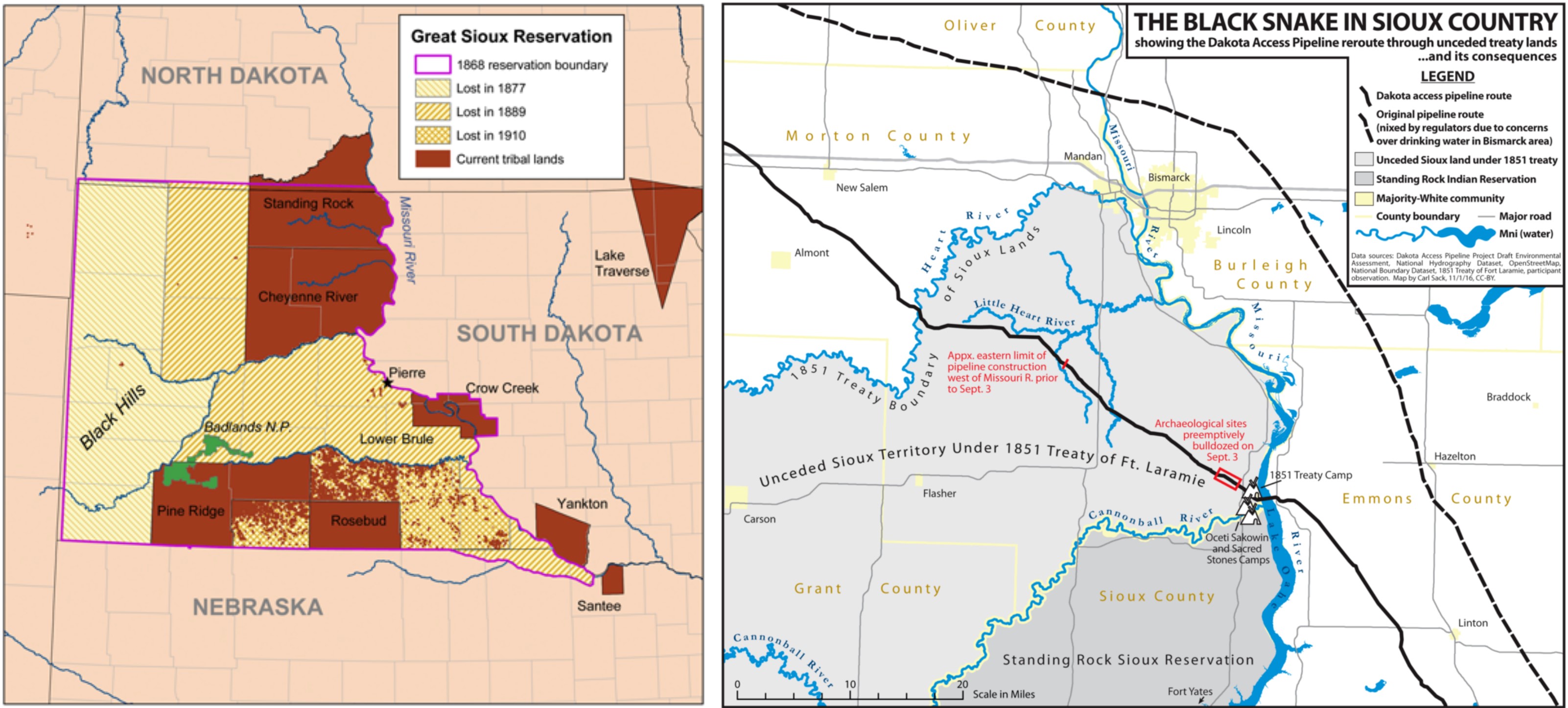

On the left, a map of the Great Sioux Reservation (red) and the land lost by the Sioux since 1868 (yellows). On the right, a map of the Dakota Access Pipeline route (solid line) and the original pipeline route (dashed line) that was changed due to concerns over drinking water in Bismarck.

One of the considerations that Indian peoples received for each of their numerous cessions was a written record of their domains’ new boundaries. Some treaties, like the United States’ early accords with the Creeks and Chickasaws, directed chiefs to accompany the surveyors marking the boundary lines, which legitimized the land sale but also defined the boundary as a binational creation.

Native peoples considered these boundaries jurisdictional borders, over which neither white sojourners nor American state laws could pass without their consent. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this position as early as 1832, when in Worcester vs. Georgia it grounded the Cherokees’ immunity to Georgia state law in their treaties with the United States and their precisely defined borders.

Treaties, however, obliged Indians to rely on the U.S. government to police their borders (much as modern Liechtenstein relies on Switzerland), and if an American president refused to enforce the law they were out of options. Lots of luck with the Georgians, President Andrew Jackson effectively told the Cherokees.

Indian treaty-makers did not always concern themselves with the question of who exactly comprised the people residing within Native American nations. Periodically, though, treaty negotiators did discuss national populations, and treaties implicitly or explicitly addressed membership in the sovereign community.

In several land-cession treaties in the late 1820s, the Potawatomis and Ho-Chunks (Winnebagos) of southern Michigan and Wisconsin awarded dozens of land grants to multiracial families joined with them by blood or marriage. The grants helped support people for whom the signatory chiefs felt responsibility, and as importantly identified the specific relationship that bound the grantees to the nation: “Indians by birth,” “married to an Indian woman,” “of Indian descent,” and so forth.

These stipulations asserted an indigenous right to determine who belonged to the nation and had a claim to its resources, and why. Indian leaders did not always get the chance to assert this right, however.

After the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles) of Oklahoma sided with the Confederacy in the Civil War, the victorious Union obliged them in their peace treaties to emancipate their African-American slaves and grant the freedpeople citizenship in their nations. The Five Tribes met this demand with varying degrees of resistance.

Most importantly, in creating and enforcing these requirements, the United States’ commissioners were arguably affirming the sovereignty of the Oklahoma Indians: the freedpeople would become Native national citizens and were therefore joining autonomous political communities.

Treaties and Resources

Treaties usually focused not on who lived within an Indian nation, but who had custody of its national resources. Land was perhaps the most important resource, but rights to game animals, fish, and wild plants also remained central to all treaties.

|

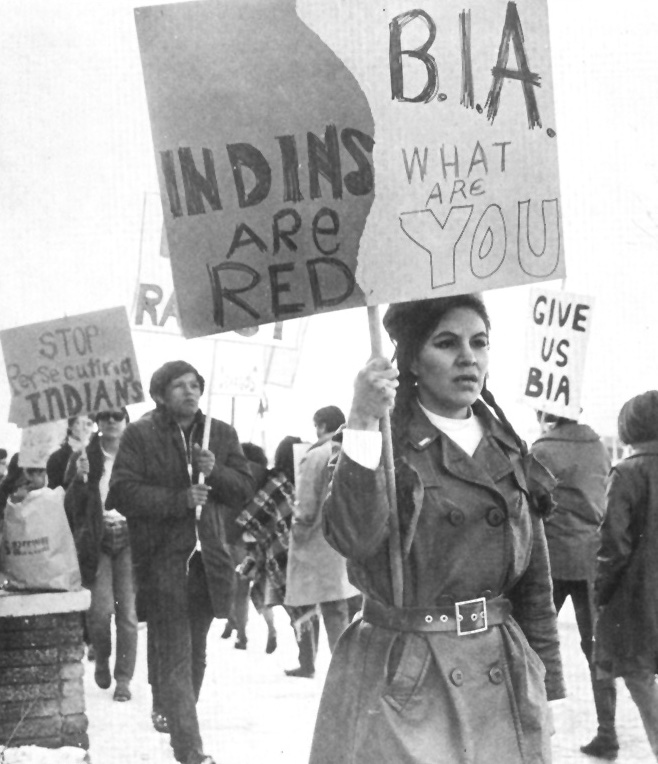

| Members of the Native American Youth Council demonstrating against the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1970. |

For example, the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, the 1837 Treaty of Saint Peters, and the 1855 Treaty of Camp Stevens granted the Great Lakes Indians and the Cayuse and Umatilla nations the right to hunt, fish, and gather on lands they had ceded to the United States. State governments would later try to curtail some of these treaty rights through their property or fish and game laws, inspiring “fish-in” protests in the Pacific Northwest during the 1960s. Federal courts eventually disallowed these violations of treaty rights.

A more ubiquitous, if potentially troublesome resource that Indians secured by treaty was federal funding for education: schools to teach their children English literacy and numeracy, and aid and training for men and women who wished to become commercial farmers, artisans, or weavers. Education funds and teachers, which the United States provided under its various “civilization” programs, carried with them a heavy freight of cultural imperialism; increasingly, they came not merely as compensations for land sales, but as coercive mandates.

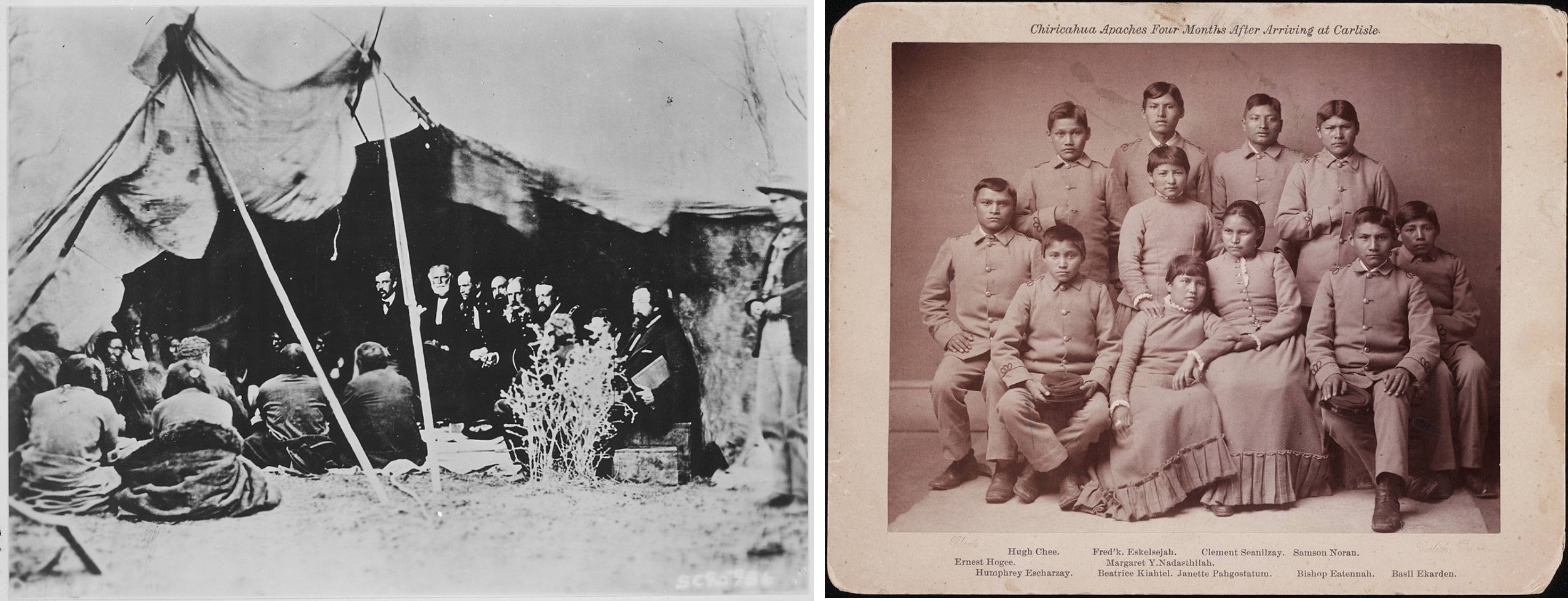

The 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge and the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, to take two prominent instances, bound the Cheyennes, Arapahos, Lakotas, and other signatories to “compel their children … to attend school.” The 100,000 American Indian children whom agents or parents sent to distant boarding schools often found them hostile environments, built around a harsh and alienating discipline, and rife with illness and unhappiness.

General William T. Sherman meeting with Indian Chiefs at Fort Laramie, Wyoming in 1868 (left). Apache children at the Carlisle boarding school in Pennsylvania in the 1880s (right).

Not all Indians, however, had the same relationship to federal education: treaties signed by the Choctaws and Shawnees (among others) gave Indian leaders control over their school funds, which gave them say over where and how their youth were educated. They could view treaty-mandated school funding as a national asset rather than an externally imposed burden.

Many Indians also realized that federal schooling and “civilization” funds could bolster their independence. English literacy and numeracy would make it harder for land negotiators and businessmen to cheat their children, and raising livestock and food crops allowed nations like the Odawas to fight against land loss and removal, on the grounds that Indians who farmed (or, more precisely, whose men farmed—most Native American women already grew crops) had a stronger legal claim to the soil than those who hunted.

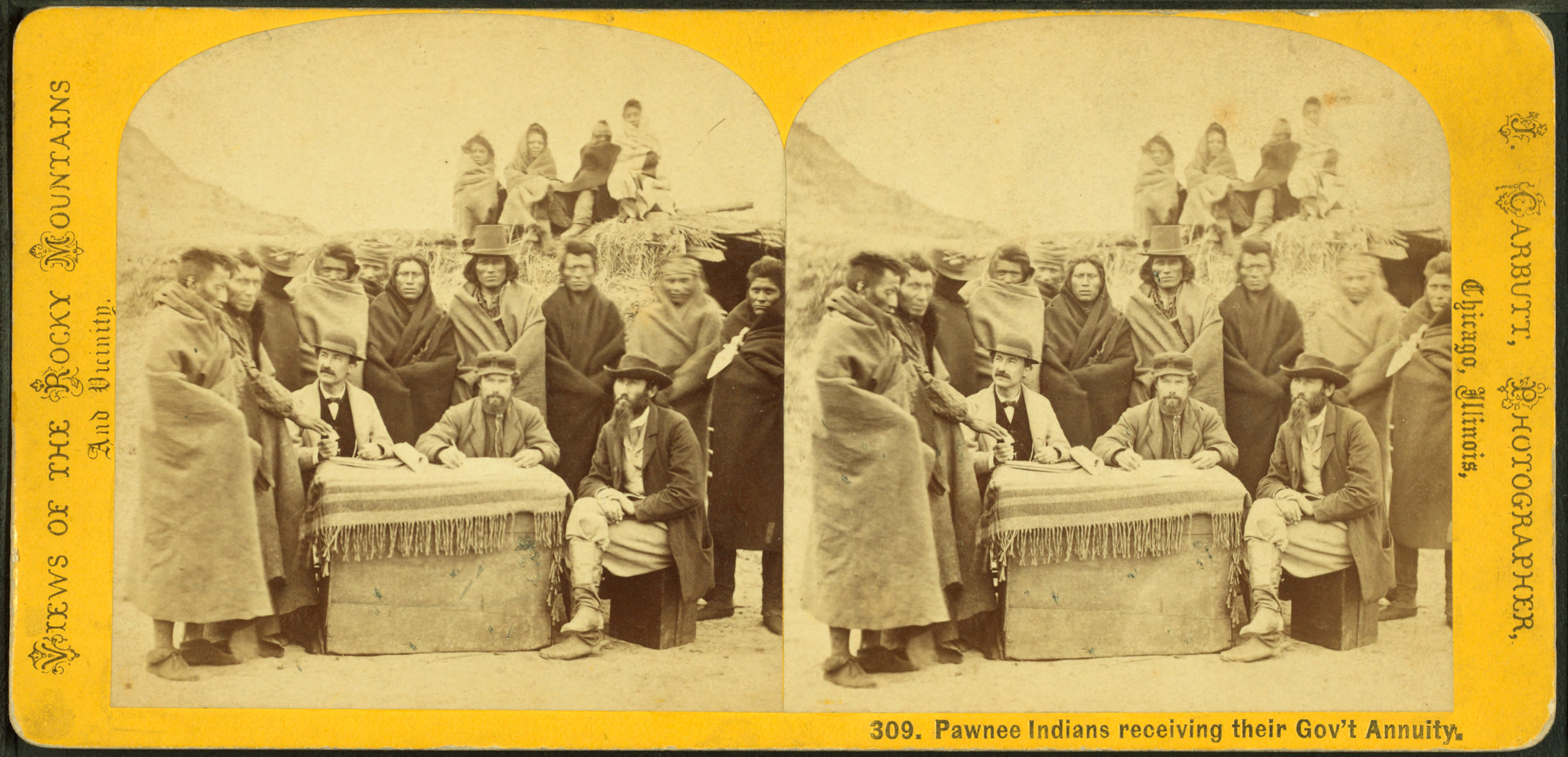

There were other compensations, larger if riskier, for Indian treaty signatories. The United States’ favored mode of payment for Indian land cessions was the annuity, an annual payment of cash and/or goods that officials first paid to national chiefs and then (after the 1840s) distributed on a per capita basis. Federal officials considered annuities a secret weapon in their government’s hands, regularly renewing Indians’ dependence on the federal government.

Pawnee Indians receiving a government annuity in the 1890s.

Some readily turned that weapon on Native American leaders and families. In 1809 future president William Henry Harrison threatened to withhold annuity payments from the Miamis and Potawatomis unless they ceded 3 million acres to the United States. Seventy years later, Congress refused to give the Lakotas their promised annuities and rations unless they surrendered the sacred Black Hills. (In 1980 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the seizure illegal and approved monetary compensation for the Lakotas. They did not accept it.)

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, some agents told parents that they would not receive their annuities unless they sent their children to boarding schools. Conversely, philanthropic white reformers like George Manypenny, head of the U.S. Office of Indian Affairs (1853-57), believed that dependence on annuity payments demoralized and degraded Indians. He favored replacing all of them with one-time cash settlements.

The Ceremonies of Treaties

American Indians generally did not agree with Mr. Manypenny. They recognized the danger of economic dependency, but they also believed that annuities had a political significance that transcended their simple economic value. The Six Nations of Iroquois received a $4,500 annuity for signing the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, and took part of their payment in textiles.

For more than 220 years, down to the present day, Iroquois leaders have commemorated the Canandaigua treaty as the foundation of their sovereign-to-sovereign relationship with the United States, and have received and distributed the annuity cloth, affirming the treaty’s continuance. The cloth doesn’t go very far (a yard or two per person), but it conveys a clear message to the Six Nations: you are nations and another sovereign sees you as such.

|

| A 2013 commemoration of the Treaty of Canandaigua in Syracuse, New York. The banner calls on Native treaties to be honored. |

An Odawa chief made the same point when in return for a large land cession he requested not only a tribal annuity but a gorget (neckplate) inscribed with “The Odawa nation is entitled to 800 dollars a year forever by the [1807] Treaty of Detroit.” The key words here were almost certainly nation and forever. Odawa nationhood preceded the Treaty of Detroit, but the treaty’s annuity provision provided an annual and perpetual proof of their sovereign identity.

Actual annuity distributions offered not just gorget-wearing chiefs but all of the recipients the opportunity to gather and renew the social ties that underpinned their national unity. In the 1850s Ojibwas turned annuity days into festivals of dancing and performance, celebrations of Ojibwa cultural continuity that attracted not only Indian but white spectators. Later in the century, the Arapahos treated annuity distributions like the American Fourth of July, a time to dress up, visit friends and relatives, socialize, and feast.

Annuities, school funds, and fishing rights were contested goods; all remained subject to outside manipulation. But they did become public goods, which Native Americans held or drew in their collective capacity, under sovereign-to-sovereign agreements.

The Ojibwas’ and Arapahoes’ conversion of annuity days into holidays and public performances reminds us that Indians did not consider sovereignty an external grant or gift, something conveyed solely by written documents and official recognition by a foreign government. Sovereignty grew from a people’s collective national identity and the social bonds that supported it. Sovereign identity was constructed and reconstructed and was regularly and publicly asserted.

Herein lies the reason why Indians considered a treaty something larger than a sealed and signed document: To them, the more important meaning of “treaty” was the large public conference where men and women gathered to negotiate and solemnize interethnic agreements.

As with annuity distributions, Indians often attended treaty conferences en masse, to represent the bands, clans, and political classes (chiefs, warriors, and matrons) that comprised their nations, and to show by their numbers the broadest display of internal consent. Nine hundred Cherokees, for example, attended the 1785 Hopewell treaty conference; 6,000 Potawatomis came to the 1833 Treaty of Chicago; and over 10,000 Lakotas, Cheyennes, and other northern Plains Indians gathered at Fort Laramie for their 1851 treaty.

|

| A statue in Fredericksburg, Texas commemorating the 1847 peace treaty between the Comanche and white settlers. |

The attendees came not just as spectators or behind-the-scenes discussants. Many played a role in ritually consecrating the treaty ground and creating a political bond with American treaty commissioners. Iroquois men and women performed stomp dances like Standing Quiver, in which on at least one occasion they invited white officials to join.

Muskogee (Creek) Eagle Tail dancers touched treaty commissioners with white eagle wings before seating them on white deerskins before a white pole. White signified peace in the Native southeast, and the Eagle Tail Dance might pacify and purify the Americans’ troubled minds. In the Great Lakes region and on the northern Plains, the ceremonial tobacco pipe known as the calumet served an analogous social and ritual function. Tobacco soothed the mind and stomach, and its smoke joined white and Indian imbibers to one another and to the celestial realm.

Dance and ritual helped legitimize treaty councils, establishing social and spiritual bonds, but for Native peoples oral addresses comprised, arguably, the most important parts of treaty assemblies. Indian speakers devoted considerable time to ensuring that everyone understood their speeches, taking time to discuss their content with their kinsmen beforehand, and then speaking slowly to allow time for translation.

The Iroquois and Great Lakes Indians often gave their listeners strings and belts of wampum, or ceremonial shell beads, to emphasize the solemnity of their words—wampum was difficult to make and northeastern Indians did not give it away lightly—or used wampum belts as aides-memoire, to help recall the content of particular “talks.”

Native American speakers also used metaphors to help listeners understand them, and to compound the solemnity of the conference. Through metaphors, speakers figuratively opened their counterparts’ eyes and ears, dried their tears, and wiped away their blood. They drew attention to clear skies and brightly burning conference fires, helping put bad memories aside and focusing on a better present. Many of these figures of speech originated with the Iroquois, but by the late eighteenth century they had spread throughout the eastern United States.

The Huron-Wendat captain Tarhe (The Crane) thought their origin sacred, calling diplomatic metaphors “the emblematic language that the Great Spirit gave to his children.” Modern legal scholar Robert Williams (Lumbee) draws our attention to another important function of this figurative language: it was “jurisgenerative,” laying the verbal groundwork for a “binding treaty relationship of law.”

By emphasizing the common suffering and hopes of whites and Indians, Native American diplomats acknowledged the two groups’ common humanity, and recognized white Americans’ standing, as fellow humans, to negotiate with them.

Speeches served another important purpose: they allowed chiefs and captains to assure American officials that they spoke for something larger for themselves, invoking the constituent groups that made up their nation. Chickasaw leaders Mingatushka and Mountain Leader presented American commissioners at the Hopewell conference (1786) with a medal owned by “the daughter and mother” of some of the “great men of our nation,” reminding listeners that their identity as Chickasaws grew from their female-line relationships (matrilineages).

Great Lakes Indian leaders signed the Greenville treaty (1795) as members of specific nations or towns, and some used pictograms to signify their clan membership. In the 1830s Ojibwa town chiefs (ogemaa) took care at treaty conferences to identify the specific communities they represented and to remind everyone that their authority came from these sources.

At the same time, Native American speakers reiterated their right to associate with other Indian nations; after the War of 1812, for example, Tarhe reminded William Henry Harrison of the wartime assistance given him by U.S.-allied Delawares, Senecas, Shawnees, and Wendats, and indicated that these Indian peoples would remain culturally allied with one another.

Treaty documents might only occasionally discuss the issue of Indian national membership, but in Native Americans’ carefully composed public addresses, at the treaty councils which Indians considered coequal with written treaty documents, the issue of identity assumed vital importance.

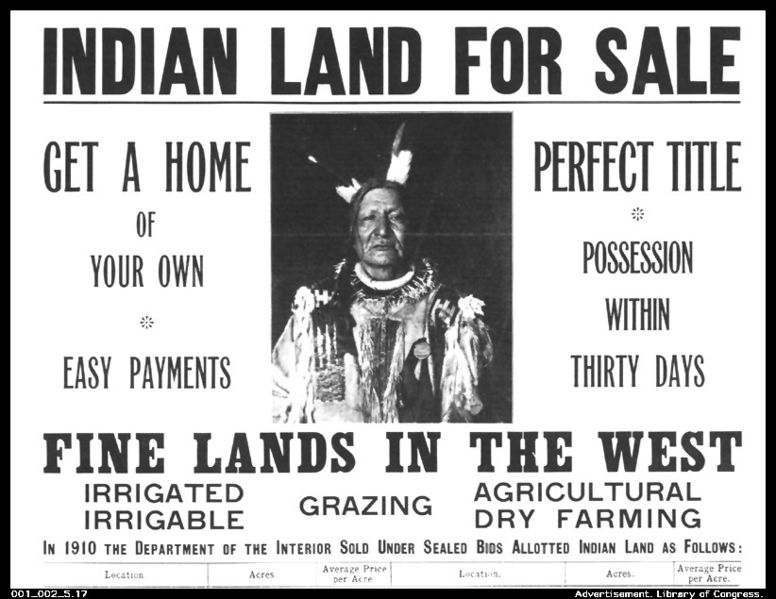

After the American Civil War, the U.S. government decided that it now only wanted Indians to hold one national identity: subjects of the United States. It saw treaties and Indian sovereignty as barriers to the work of assimilation. In 1871 Congress banned further Indian treaty-making, as a preliminary to assuming what the Supreme Court called (in Lone Wolf vs. Hitchcock [1903]) “plenary power” over Indians’ lives. A Major Crimes Act (1885) severely curtailed Native American control of reservation law enforcement, and the infamous Dawes Act (1887) allowed the Interior Department to privatize and sell Indians’ remaining communally held lands.

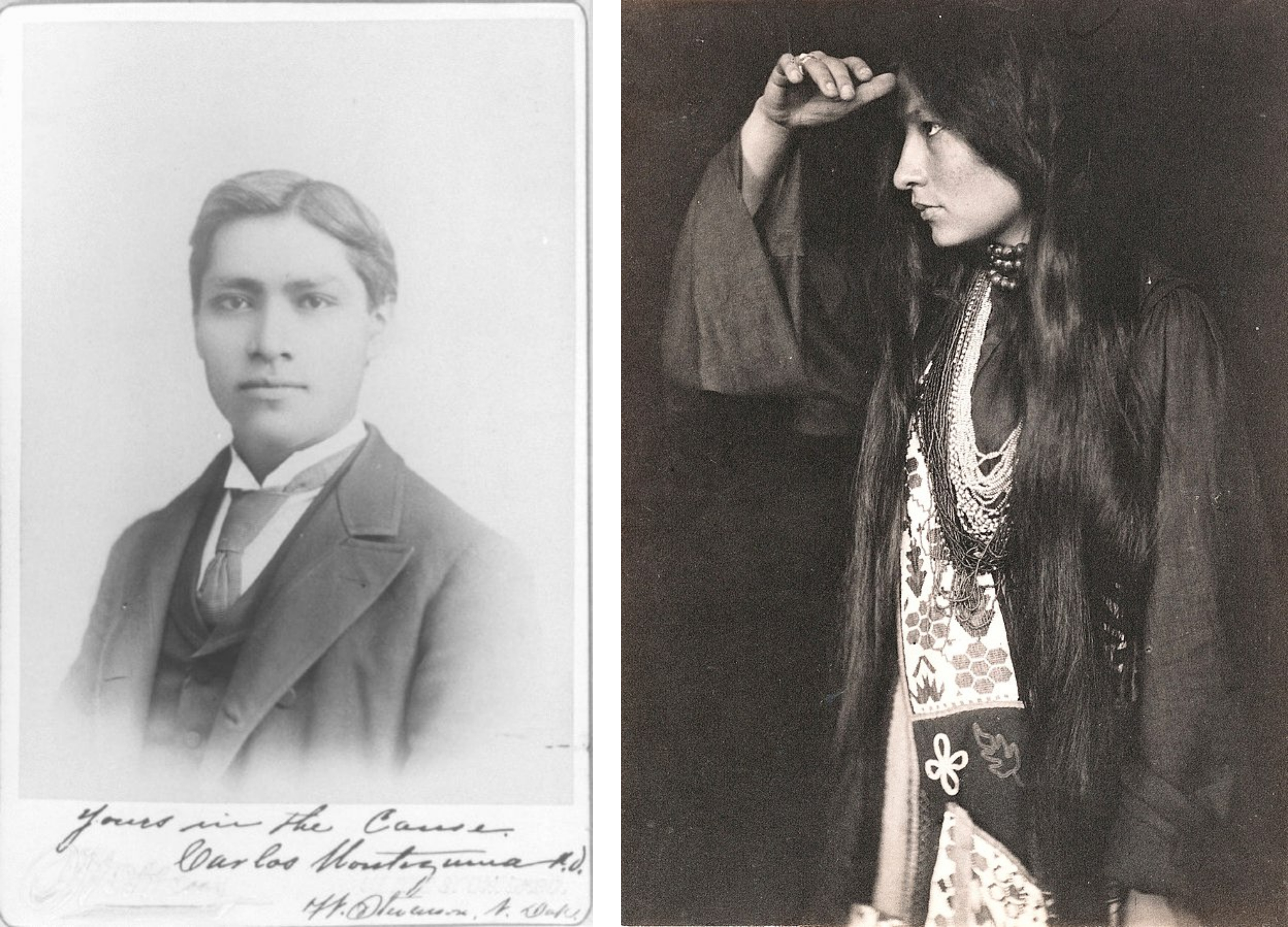

By the early twentieth century, however, white activists like John Collier and Native American reformers like Carlos Montezuma and Gertrude Bonnin concluded that the assimilation project had only produced greater poverty and isolation. In the 1930s Collier (now Superintendent of Indian Affairs) reintroduced a limited government-to-government relationship under the Indian Reorganization Act, which encouraged Indian nations to establish reservation governments and buy back their old lands. In 1946, Congress recognized the validity and violation of earlier treaties when it established the Indian Claims Commission, to compensate Indians (however parsimoniously) for lost lands.

Carlos Montezuma as a young man in 1890 (left). Gertrude Bonnin in 1897 (right).

During the 1960s, activists like Clyde Warrior argued that Indians’ real wealth lay in their sovereign right of self-government, and a decade later Congress moved toward partial restoration of Native American autonomy through the Indian Self-Determination Act (1975) and the Indian Child Welfare Act (1978), giving tribal nations more control over federal funds and the protection of children.

Thanks in large part to Indian activism, the U.S. government now sees Native American sovereignty not as an anachronism but a legal reality.

NODAPL and Native American Sovereign Rights

As for treaties, the United States might not make them any longer, but the 400 negotiated between 1778 and 1871 remain living documents. One can still hear echoes of the treaty era at Standing Rock today.

A nineteenth-century Indian civil chief, warrior, or matron, transported somehow to the encampments on the Cannonball River in 2016, would see many unfamiliar sights, but the social environment would seem familiar.

Protesters in Standing Rock insisting that treaty rights and sacred ground be respected.

The thousands of protesters encamped near the DAPL site use sweat lodges and burning sage to purify themselves and their ground. They follow rules of conduct laid down by Sioux officials. They gather non-violently, women, men, and children alike. They talk of boundaries, of past treaties, and of protecting the remains and sacred sites of their ancestors. The NODAPL protests, in short, have much in common with nineteenth-century treaty conferences.

Against this nonviolent, collective demonstration of sovereignty, and against the justice of the protesters’ demands, those elements that “realists” would consider the alpha and omega of national sovereignty—money, military power, and the carceral state—stand in grim array. Which vision will win I know not, but in both American and Native American history it is not always a sure bet to back the state against the nation, or the nations.

The author thanks Susan Livingston and Katherine Osburn for their editorial assistance and suggestions.

Listen to Origins for more on Native American Sovereignty: Native Sovereignty and the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Colin Calloway, Pen and Ink Witchcraft: Treaties and Treaty-Making in American Indian History (New York, 2013)

Brenda Child, Holding Our World Together: Ojibwe Women and the Survival of Community (New York, 2012)

Dorothy Jones. License for Empire: Colonialism by Treaty in Early America (Chicago, 1982)

David Nichols. Red Gentlemen & White Savages: Indians, Federalists, and the Search for Order on the American Frontier (Charlottesville, 2008)

Francis Prucha. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly (Berkeley, 1994)

Robert Williams, Linking Arms Together: American Indian Treaty Visions of Law and Peace, 1600-1800 (New York, 1999)