In the early hours of April 26, 1986, the staff of the 4th Reactor at the Chernobyl’ nuclear power station in Ukraine, then a republic of the Soviet Union, conducted tests that went wrong. Trying to correct the problem manually, they switched off the automatic system designed to shut down the reactor.

The result was disaster.

A power surge led to a series of explosions that blew off the roof (weighing 12,000 tons), caused a fire inside the reactor that burned for ten days, and spewed radioactive vapor and particles up into the atmosphere and onto the surrounding land. Over the following days and weeks, a radioactive cloud spread over much of Europe.

Aerial view of the destroyed reactor, 1986 (left), and radioactive cloud (right).

Fire fighters and power station workers struggled to put out the fire. Two people were killed in the explosion and around 28 were exposed to fatal doses of radiation. The power station management and authorities in Kyiv, the capital of the Ukrainian Republic, tried at first to conceal and minimize the accident. Only when the radioactive cloud was detected over Sweden did the full extent become known to the authorities in the Soviet Union’s capital in Moscow and to the wider world.

Over the next few months, hundreds of thousands of people, mostly military conscripts and reservists, were mobilized in a desperate struggle with the consequences of the explosion. They became known as “liquidators.” Robots were used, but some could not cope with the high levels of radioactivity. Instead, people (“biorobots”) were sent in, with minimal protective clothing, and serious and sometimes fatal consequences for their health.

Robots, now cleaned up and on display near the doomed reactor, 2016 (left, photo by Anna Olenenko), and ‘Biorobots’ clearing radioactive debris from the roof of the reactor (right).

In the months after the explosion, workers and robots built a shelter over the destroyed reactor. Known as the “sarcophagus,” it also serves as a monument both to the heroism of the “liquidators” and the human folly that caused the disaster. While the sarcophagus was being built above ground, miners tunnelled underneath and installed a cement shield to try to prevent the reactor core, which had melted, from contaminating the ground water.

Twenty years after the disaster, it was revealed that the “liquidators” had averted a far more serious, second explosion, with the destructive force of a 3-5 megaton atomic bomb, which would have left large parts of Eastern Europe uninhabitable for generations.

Monument to "those who saved the world." (Photo by Anna Olenenko)

When we—an international, multi-disciplinary group of scholars—visited in June 2016, we posed for a sombre photograph in front of the sarcophagus.

Group in front of sarcophagus. (Photo by Voicu Sucala)

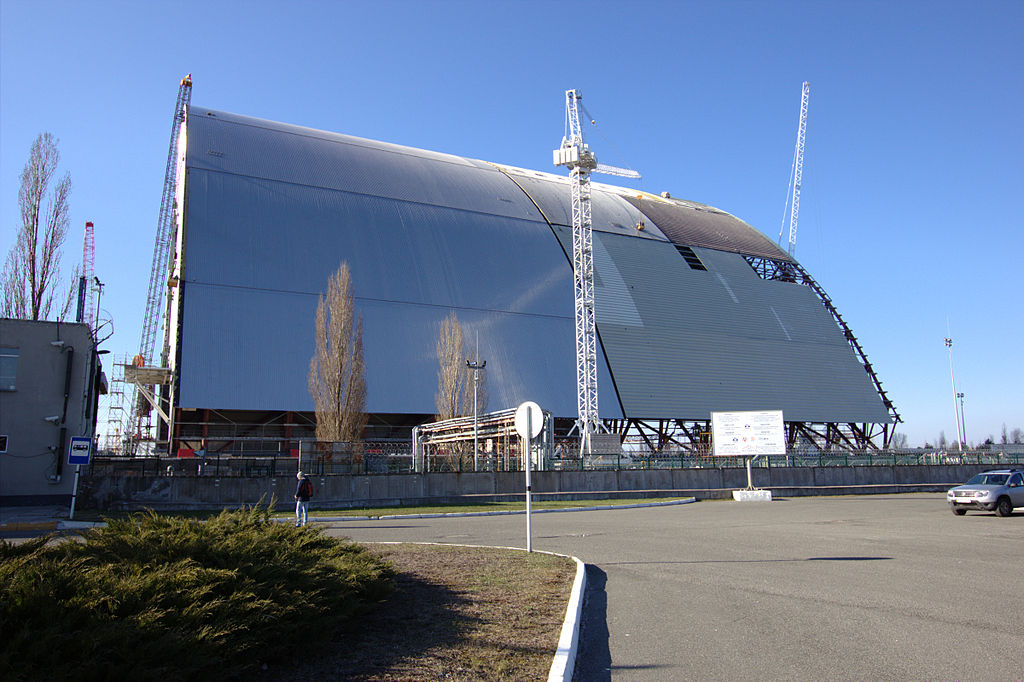

Near the reactor is the larger “new safe confinement,” nearing completion, which will slide over the decaying sarcophagus. Built at a cost of over $1.5 billion with funding from many countries, it is planned to protect the environment from further contamination until it is possible, in a few decades time, to dismantle and dispose of the still highly-radioactive remnants of the explosion.

New Safe Confinement nearing completion.

After the explosion, to the eternal shame of the authorities, the surrounding population was not evacuated immediately and iodine, which could have helped avert health consequences, was not distributed promptly to all those who could have benefitted, especially the children. The authorities allowed parades to celebrate May Day, a major Communist festival, to go ahead in the towns and cities around the disaster area, including Kyiv and Minsk, the capital of the adjoining Belorussian republic. Millions were exposed to the radioactive cloud.

Pripiat’: A Moment Locked in Time

Most of the power station’s workers and their families lived in Pripiat’, a model town built to house them. Pripiat’ was evacuated two days after the explosion. The abandoned town lies deserted, looted of anything of value (in spite of the radioactivity), and thoroughly vandalised.

We tramped around and went inside the kindergarten, school, sports center, stadium, hospital, apartment blocks, and the amusement park with its carousel, dodgem cars and ferris wheel. Peeling walls, collapsing ceilings, broken floors, and above all the crunch, crunch, crunch of broken glass under our feet accompanied us at every step.

Pripiat’. (Photo by Voicu Sucala)

Pripiat’. (Photo by Voicu Sucala)

Pripiat’. (Photo by Voicu Sucala)

The ruins of Pripiat’ are trapped in a time warp of the 1980s. The faded Soviet posters and slogans, the fizzy water vending machines, and the school text books all created a bizarre sense of nostalgia for those of our group who had been exchange students in the Soviet Union or had lived there as children. Glimpses of a lost, Soviet world, we thought never to see again.

Poster on Civil Defense in the event of a NATO nuclear attack on classroom wall (left, photo by Voicu Sucala), and rusty fizzy water vending machines (right, photo by Nadia French).

An enduring memory of our visit will be the forest that has returned to the town. Public squares, sidewalks, roads, the sports field, amusement park, even the insides of buildings have been taken over by the native vegetation. Pripiat’ is now a thirty-year-old forest.

The view from the roof of an apartment block with more forest than buildings. (Photo by Anna Olenenko)

Nature in the Exclusion Zone

Nature was severely harmed by the explosion and radioactive debris. The pine forest next to power station turned red from radioactivity. “Liquidators” felled, chopped up, and buried the radioactive trees of the “red forest.” Thirty years on, a new pine forest has grown back.

The “Red Forest” after the accident.

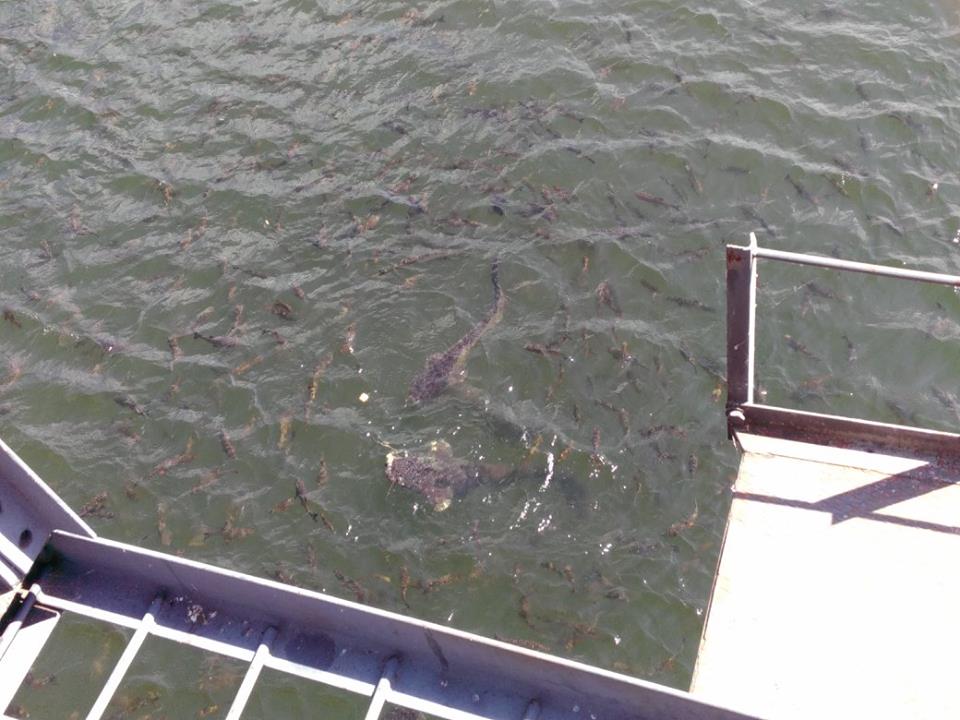

Slowly, after the explosion and the evacuation of the population, nature has returned to the “exclusion zone” inside a 30 km radius of the power plant. We saw not just trees, but flowers, insects (including butterflies), birds, and caught glimpses of larger mammals that live in the forest. Chris Thomas, an ecology professor in our group, regularly went off to look at the flora and fauna. Some of our group heard wolves howling during the night we spent in the hotel in Chernobyl’. In the cooling pond near the power station we saw ominously large cat fish.

Cat fish in cooling pond. (Photo by Anna Olenenko)

The cat fishes’ size was not because they were radioactive mutants, but because they were left in peace by their main predators: humans. Nature has become resurgent when its main, human, rival has left. Chernobyl’ has become an unexpected nature reserve.

Which is more harmful for “nature”: humans or radioactivity? Some scientific studies indicate an abundance of wild life, especially large mammals, including bears, wolves, deer, living in the exclusion zone largely abandoned by people. Others scientists urge caution, and point to long-term health effects on the wild life as a result of the radioactivity.

Visitors to the World’s Worst Nuclear Accident

We were permitted to visit the exclusion zone on an official tour. We were stopped at check points at the entries to the 30 km outer and 10 km inner zones and checked for radiation when we left. To advise us on the risks and precautions, we had a radiation protection officer, Dr Ian Haslam of the University of Manchester, in our group. He advised us of the risks, the need to wear closed footwear, long trousers and sleeves, not to stray from the roads and paths, which had been cleaned, not to touch or eat or drink anything in the open air, and to wash ourselves and our clothes thoroughly after we left.

He monitored the radiation with his dosimeter and Geiger counter. He explained his readings. Some were quite low in the outer zone, not much higher than in the nearby city of Kyiv. Inside the 10 km inner zone, near the reactor and red forest, they were higher. And there were hotspots, away from the roads and paths, where radioactive debris from the explosion had sunk into the soil. A lethal dose of radioactivity—which proved fatal to some of the power station workers, fire-fighters and “liquidators” in the aftermath of the disaster—is many, many times the low levels we were exposed to on our two-day visit.

Dr Ian Haslam with Geiger counter and dosimeter. (Photo by Voicu Sucala)

Before our trip, Ian advised us that a short visit to the zone would not cause long-term consequences for our health, if we followed the safety advice. Far, far less fortunate were those people lived and continue to live in the region around the disaster zone.

Debate rages about the total deaths, and likely future deaths, that can be attributed to the disaster. Estimates vary from 4,000 to 93,000 and more. The differences can be explained partly by difficulties in attributing cancers and other diseases directly to the disaster and to disagreements over the health consequences of exposure to low-level radiation.

The divergences in opinion also seem to depend also on who is doing the calculations and where their interests lie. The United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency (IATA) and World Health Organization (WHO) are responsible for the lower estimates; independent scientists and non-governmental environmental organizations for the higher.

Credits

Our visit to the Chernobyl exclusion zone was funded by the Leverhulme Trust << https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/ >> and the Georgetown Environment Initiative << https://environment.georgetown.edu/ >>, and was part of a larger project on environmental history. https://www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/features/russian-environmental-history/

Resources

‘The Battle of Chernobyl’, documentary film, 2006.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1tj4nruBZg

Books:

Svetlana Alexievich, Voices from Chernobyl (New York: Picador, 2006)

(Oral history by Nobel Prize winning author)

Mary Mycio, Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl (Washington, DC, Joseph Henry Press, 2005)

(Account by journalist who, to her surprise, found ‘thriving’ flora and fauna in zone)

Selection of articles offering differing perspectives:

Kate Brown, “Eating at You: Food and Chernobyl,” Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, April 2016

/milestones/april-2016-eating-you-food-and-chernobyl

Jim Green, “Chernobyl - how many died?” The Ecologist, 26th April 2014

http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2370256/chernobyl_how_many_died.html

Timothy J. Jorgensen, “Forget Fukushima: Chernobyl still holds record as worst nuclear accident for public health,” The Conversation, April 25 2016

David Moon and Anna Olenenko, "Interview with Ivan Ivanovich Semeniuk - a returnee to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone," The Ecologist, 25th November, 2016

Timothy A. Mousseau, “At Chernobyl and Fukushima, radioactivity has seriously harmed wildlife,” The Conversation, April 25 2016

Mike Wood and Nick Beresford. “Wolves, boar and other wildlife defy contamination to make a comeback at Chernobyl,” The Conversation, 5 October 2015

World Health Organization, “Chernobyl: the true scale of the accident,” 2005

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr38/en/

Multimedia project by Russian journalists who visited exclusion zone in early 2016: “The Land of Exclusion: Chernobyl and its Surroundings Today – A Kommersant Special Project,” April 21, 2016. http://kommersant.ru/projects/chernobyl/en