When our group of sixteen historians and geographers arrived on the banks of Russia’s Kama River on 11 July 2016 for an intense five-day excursion through the Perm-Ekaterinburg region, we followed a venerable tradition of Urals travel and exploration.

Naturalist Johann Gmelin (1709-55) was so captivated by the industrial sites of “Catharinenburg” that he visited twice—on his path to and from Siberia in 1734 and again in September 1742, commenting from Nev’iansk: “I had little interaction with humans here, and didn’t desire any, because other matters were more useful. The foundries, mines, factories, and animals were for me more reasonable objects of interest, and more fit to shape and illuminate my mind.”

Modern chemical factory in Berezniki, across the Kama from Usol’e.

Our interests were quite similar to Gmelin’s: our group was pursuing the themes of “industry, mining, transport, and industrial heritage tourism.” The site of early modern Russian industrial production, the Urals tell a rich tale of mineral resources and their exploitation from the sixteenth century to the GULag labor-staffed chemical and metallurgical plants of the twentieth.

The Urals made Russia into Europe’s primary iron exporter in the eighteenth century, as well as a key producer of iron and steel for domestic use in the railroad age of the nineteenth. Urals industry received a new, albeit grim, lease on life with the massive evacuation of industry from Ukraine and the Donbass during the Second World War. The “factory-cities” of the Urals region today form a unique cultural space, with a vibrant international commercial life and a powerful presence on the literary and theatrical scene.

Perm and the Saltworks

On the morning of the 12th, we set off for Solikamsk and Usol’e to the north of Perm, where we were instructed in early modern techniques of salt extraction. Crucial to the preservation of food, salt was in high demand throughout Russia for every social class.

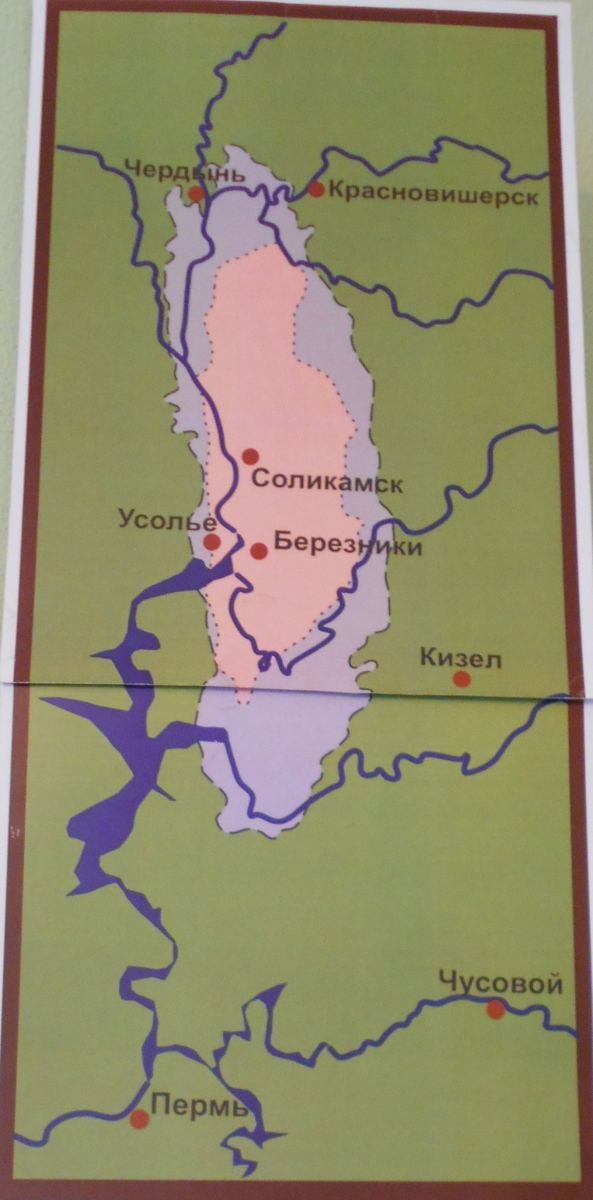

The geographic distribution of salt (purple) and potassium salts (pink) in the upper Kama region.

Master artisans at the saltworks, now concentrated in a special Salt Museum at Ust’-Borovsk, extracted salt and water from underground, boiled the viscous mixture using special ovens, and dried out the salt crystals on wooden planks.

Mechanism for extracting salt (left) and boards on which the salt crystals evaporated (right).

The salt was transported to market by barge, and loaded by men and women with enormous bags on their backs. The norm is said to have been 48 kg for women and 80 kg for men.

We also visited the residence of the Urals salt magnates, the Stroganov family, at Usol’e, narrowly missing a huge downpour as we arrived. The Stroganovs were the virtual lords of the Perm region in the sixeenth and seventeenth centuries. Granted privileges and lands based on their success in salt production by Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible), they vied with the great monasteries for control over the salt business in all the Muscovite lands, and expanded their vast commercial empire into agriculture, fishing, hunting, and mining.

Church and belltower at Usol’e.

Stroganov residence at Usol’e, 1720s.

The following day, we visited the nearby outdoor museum of wooden architecture, with its fascinating reconstruction of middling and rich Komi and Russian peasant houses, adapted to frigid climes; and had time to drop in at the Perm Museum of Contemporary Art and the Perm campus of the Higher School of Economics.

The Perm Museum of Contemporary Art logo.

Kungur

One of the unexpected gems of our voyage was the picturesque town of Kungur, about a third of the way on the highway between Perm and Ekaterinburg.

Kungur’s heyday was in the nineteenth century, when wealthy merchants built opulent wooden and stone houses along the inclines overlooking the Sylva river. We didn’t want to miss our chance to see the world from on high, and climbed up the belltower of the Savior Cathedral, which itself perches on the tallest hill of the town.

View from the Savior Cathedral bell tower, Kungur.

After climbing to Kungur’s highest point, nothing could make us happier than to descend equally far into the earth’s depths at the area’s most famous tourist attraction: the Kungur caverns, mapped already by geographer Semën Remezov in 1703 and then V.N. Tatishchev in the 1730s.

We pulled on parkas and silk underwear to spend 90 minutes underground. Perhaps most impressive were the perfectly still and limpid underground lakes—so clear that we needed convincing that they were actually filled with water. Even they have an inhabitant—a tiny shrimp-like mollusk.

Underground lake in the Kungur caverns. (Photo by Arkady Kalikhman)

Ekaterinburg and Iron Production

Like Gmelin, I am particularly interested in the iron foundries and factories of his own time—the large-scale enterprises that catapulted Russia into its place as the biggest iron exporter in Europe on the eve of the “industrial revolution.” Thus our final two days were a highlight, dedicated to Ekaterinburg and the almost mythically famous (so far as industrial lore goes) Nev’iansk and Nizhnii Tagil.

Several of us stared incredulously out the windows of our bus as we entered the metropolis of Ekaterinburg with its impressive skyscrapers, towering construction cranes, and fashionably dressed young people, after many kilometers of nearly unbroken forest.

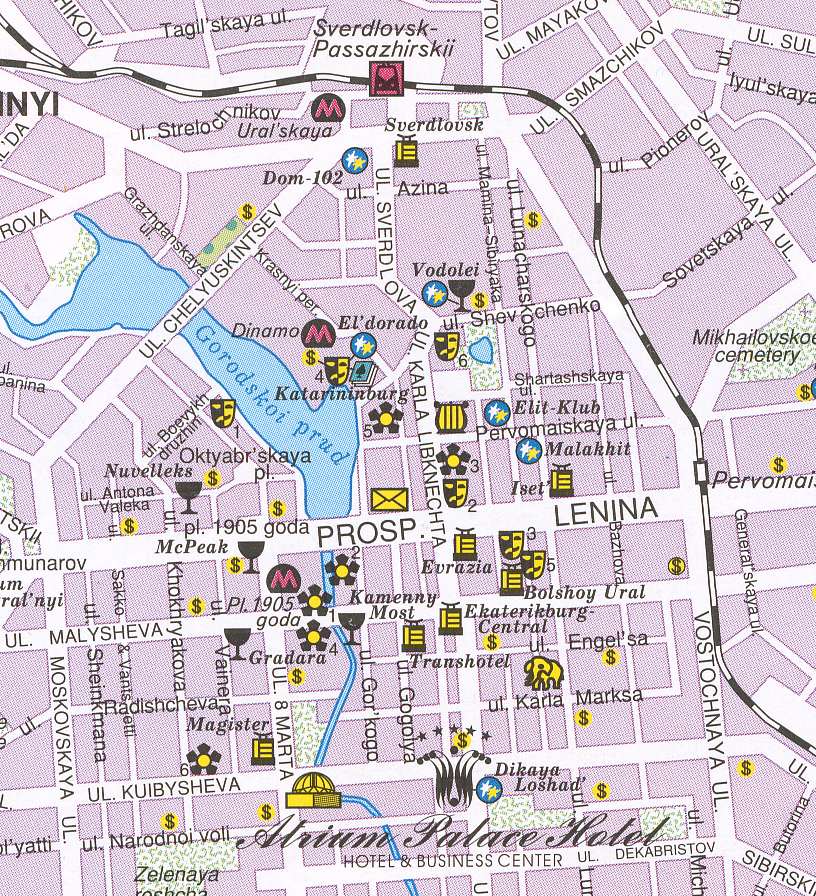

Ekaterinburg arguably represents a unique type of urban formation—the “city-factory” of the Urals. The city grew up around the iron factory of the 1720s, strategically placed to maximize hydropower, on the Iset River. The characteristic immense factory reservoir, narrowing into a thin stream beyond the dam, lies at its center.

Ekaterinburg city center, with the characteristic factory reservoir.

Our final travels took us to the leaning tower of Nev’iansk—the site of the Demidov family ironworks of the early eighteenth century, where one can observe at first hand the extremely high quality of cast iron from that time.

Nikita Demidov, son of a Tula blacksmith, founded the ironworks during the reign of Peter the Great. The business eventually expanded far beyond its original purpose of military production, and the Demidov dynasty became one of the wealthiest and most influential noble families in Europe. It was fun, and illuminating, to see the moving replica of an eighteenth-century iron factory in the local museum.

Russia’s famous leaning tower of Nev’iansk, 1720s-40s (not quite as famous as the one in Pisa... yet).

And the trip would not have been complete without the remarkable Factory-Museum of Nizhnii Tagil—a metallurgical plant that had functioned consistently from the first half of the eighteenth century up until the 1980s, and where one may now wander cautiously, invading the old industrial structures along with the plant life that has largely taken over. Nizhnii Tagil also boasts a local history museum originally established at the unusually early date of 1840.

A pipe for diversion of spring floods at the factory (left) and the factory-Museum at Nizhnii Tagil (right).

Our day concluded with a small hike up the “High Mountain” (Gora Vysokaia), which has the distinction of being some 50 meters less high than it was before industrial mining got to it—but at least it is not a crater in the ground as is this copper-rich former hill on its southern slope.

Copper crater, seen from atop the High Mountain.

We returned to St. Petersburg on 17 July, somewhat crumpled from countless hours in the bus, but thrilled by the intensity of our experiences and encounters with the heritage of the Ural mountains’ industrial and mining past.

[All photos by author unless noted, 2016]

This trip to the Urals was Funded by a Leverhulme International Network grant for the project “Exploring Russia's Environmental History and Natural Resources” https://www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/features/russian-environmental-history/ and the Georgetown University Environment Initiative.

The group included scholars from Russia, Great Britain, the United States, and Norway: Alexandra Bekasova (Higher School of Economics, St. Petersburg), Vasily Borovoy (PhD student, HSE, SPb), Margarita Dadykina (HSE, SPb), David Damtar (MA student, HSE, SPb), Catherine Evtuhov (Georgetown University), Anastasia Fedotova (Institute of History of Science & Technology, Russian Academy of Sciences, SPb), Arkady Kalikhman (Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk), Tatiana Kalikhman (Inst. of Geography, RAS, Irkutsk), Ilya Kalinin (Smolny/St. Petersburg State University), Alexei Kraikovsky (European University, SPb), Julia Lajus (HSE, SPb), John McNeill (Georgetown University), Patrick McNeill (MA student, Yale University), David Moon (York University, UK), Denis Shaw (Birmingham University, UK), Urban Wråkberg (Arctic University of Norway)