Espionage produces information. Its analysis generates intelligence. The process is priceless. This hardly constitutes a new revelation. Sun-tzu, an early fourth century BCE Chinese general who authored the earliest known text on war and espionage, Ping-fa (The Art of War) observed that, “A hundred ounces of silver spent for information may save ten thousand spent on war.” Astute then, Sun-tzu’s words still resonate today, in an age characterized by daily reports of leaks, hacks, and surveillance.

The ancient world lacked the internet and, for that matter, cell phones and cameras, yet its inhabitants appreciated the value of information and used espionage to get it. According to the Bible, Moses utilized spies, as did the Philistines. They uncovered the source of Samson’s strength, his hair, by utilizing Delilah, history’s first female spy. Since then, as this list shows, espionage became more complex and increasingly valuable. The times change, but spies remain. Here are ten of history’s top spies.

1. Sir Francis Walsingham

Walsingham, Sir Francis Walsingham, stands as the forbearer of British Intelligence, real and fictional, including one Agent 007. He acted in the capacity of Her Majesty’s original secret service, working officially as Secretary of State and adviser to Queen Elizabeth I. An impassioned Protestant, Walsingham established the secret service in London in 1573, the first national intelligence organization in England’s history. Walsingham’s fascination with codes enabled him to develop an elaborate cipher, a method of cryptography that substitutes another letter or number for every letter in a message.

England’s original “spymaster,” Walsingham established an extensive network of “intelligencers” that included his daughter Frances. It worked to suppress Catholicism at home and abroad, operating under Walsingham’s motto, “Knowledge is never too dear.” Walsingham’s efforts aided in the entrapment and execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1586. Two years later, they helped thwart the Spanish armada’s design to invade England.

2. The Culper Ring

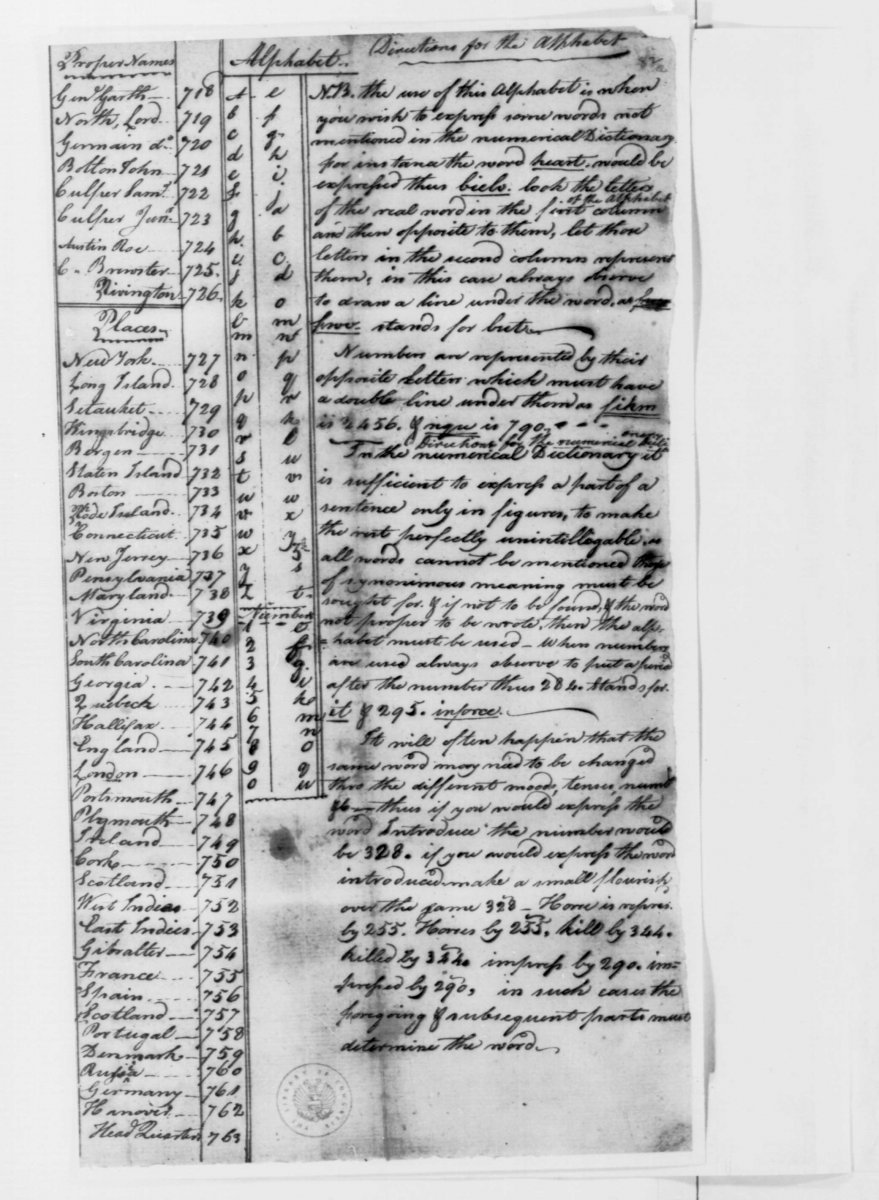

With his troops scattered as a consequence of the British occupation of New York City, in June 1778 Continental Army General George Washington ordered Major Benjamin Tallmadge to create an espionage network. Tallmadge recruited Abraham Woodhull of Setauket, Long Island who assumed the moniker “Culper Senior.” Robert Townsend, a New York City merchant recruited by Woodhull became “Culper Junior.” Woodhull and Townsend, along with Washington, shared a secret code to communicate that Tallmadge devised.

Townsend ran a coffee shop and joined a Tory militia to preserve his cover. He kept daily watch on the British army, giving his reports to Austin Roe, a Setauket tavern owner who traveled regularly to New York City for supplies. Returning home, Roe passed along the information, depositing it in a dead drop on Woodhull’s farm. In 1780, this enabled Washington to deceive the British into not attacking arriving French troops in Newport, Rhode Island.

3. The Richmond Underground

Granddaughter of Hilary Baker, the mayor of Philadelphia, PA from 1796 to 1798, Elizabeth Van Lew grew up in Richmond, VA as a member of a prosperous family. She received a Quaker education and became a staunch abolitionist. She used her inheritance from her father’s passing to free the relatives of her family’s emancipated slaves. During the Civil War, Van Lew created the Richmond Underground, a network that aided in the escape of hundreds of Union prisoners and Confederate deserters.

The Richmond Underground ran through the White House of the Confederacy where Van Lew managed to obtain employment for Mary Richards Bowser, one of her former slaves, as a servant. Bowser delivered the military intelligence she obtained to the White House baker, another agent of the Richmond Underground. Under suspicion, Van Lew avoided detection by faking insanity. After the war, Union commanders praised the intelligence that Van Lew provided them.

4. Black Ocean Society

Founded in 1881 by Kotaro Hiraoka whose wealthy samurai family resided on Kyushu, the Black Ocean Society derived its Japanese name Genyosha from the strait, or the black ocean, that separates Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost island, from Korea. The society strove to obtain intelligence and expand Japan’s influence in Korea, as well as in China, Manchuria, and Russia. It became an unacknowledged branch of Japan’s government, serving as the first organization in Japan to provide foreign intelligence by employing undercover assets.

Mitsuru Toyama became the society’s most successful leader, operating spies in China to produce military intelligence for Japan’s army. Toyama wore two swords from his waist and commanded the society’s enforcers, a band of samurai without masters known as ronin. After the society’s exposure, another of its leaders, Ryohei Uchida founded the Black Dragon Society in 1901. It fueled Japanese militarism through the Second World War.

5. Room 40

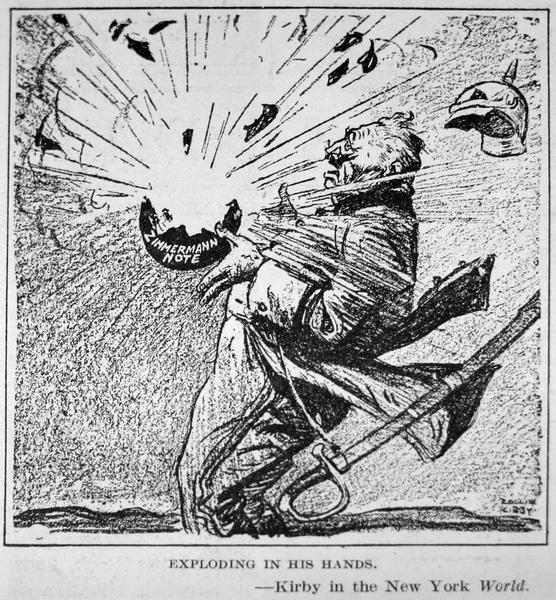

Room 40 housed NID 25, the British Royal Navy’s codebreaking operation during World War I. Its name derived from the room it occupied in the Old Admiralty Building in Whitehall beginning in October 1914. Its work benefitted from the Admiralty’s acquisition of code books, one delivered by the Russians from the German cruiser Magdeburg and another from a German merchant ship captured by the Australians.

Room 40 deciphered nearly every message the Germans sent, including those sent through seafloor cables that passed through British waters. This enabled Room 40 to intercept the Zimmerman telegram, a German invitation of alliance to Mexico that endorsed its recapturing of territory earlier lost to America. Shared with American authorities, the Zimmerman telegram helped bring the United States into the war. After the war, the British merged NID 25 with its parallel department in Military Intelligence, MI1B to form the Government Code and Cypher School.

6. Margaretha Gertrud Zelle “Mata Hari”

Born in Holland, Margaretha Gertrud Zelle became Mata Hari (Eye of Dawn) in 1905 after moving to Paris and assuming the persona of a Javanese princess and working as an exotic dancer. She performed throughout Europe and in Egypt acquiring a procession of wealthy and influential lovers along the way. During World War I, Mata Hari’s Russian lover, a pilot serving France, suffered wounds and landed in a forward hospital. French officials let Mata Hari visit him in exchange for her agreement to spy on Germans.

Mata Hari never made it to her Russian lover’s bedside. Instead she found another, a German military attaché who identified her as a spy in a message read by the Allies. This led to her arrest and execution, despite little evidence against her. Mata Hari is one of the most famous spies in history even though she likely never actually spied.

7. Station X

Located 50 miles north of London, Bletchley Park, designated as Station X, constituted the evacuation point for MI6, the British Secret Intelligence Service, at the onset of World War II. It quickly became the site for the British Code and Cypher School, headquarters for a crypto analysis effort that utilized mathematicians, chess players, and linguists as codebreakers. Their work built on the prewar efforts of Polish military intelligence, which was shared with British and French code specialists, all of which produced Ultra, the deciphered intelligence from German encrypted messages.

By the spring of 1940, Station X codebreakers could read much of Germany’s communications. They utilized high speed calculating machines, first the Bombe and, by early 1944, the more advanced Colossus. These derived from the early system, devised by Polish mathematician Marian Rejewski, to crack the German encryption machine Enigma. Intelligence derived from Ultra proved crucial in many Allied victories, including the pivotal Battle of the Atlantic.

8. Atomic Spy Ring

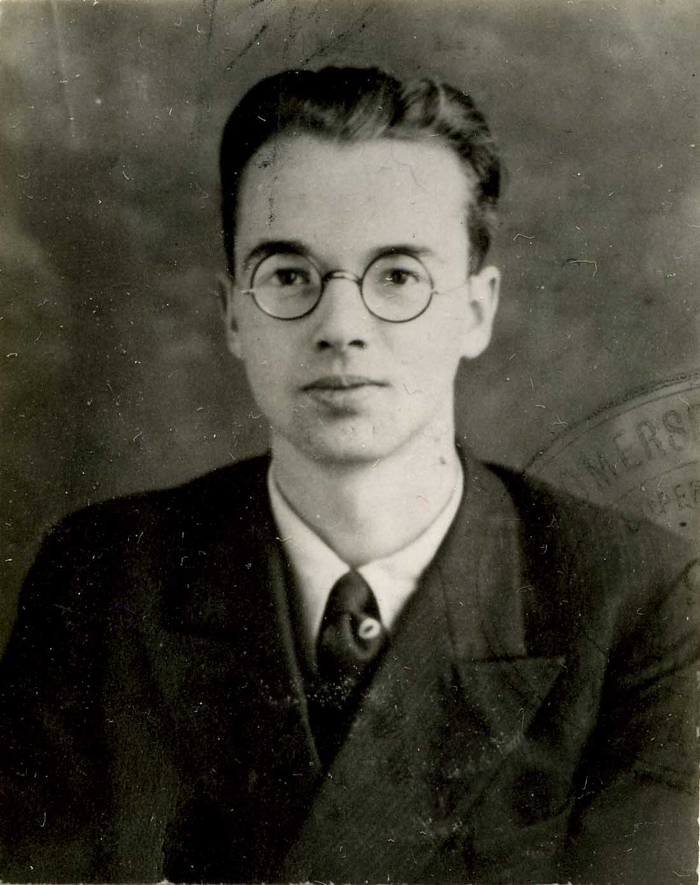

The atomic bomb project represented the most closely guarded Anglo-American secret of World War II. President Harry S. Truman only shared the information with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, part of the wartime alliance, in July 1945 at the Potsdam Conference after the first successful nuclear test. Stalin’s apparent lack of interest in the news convinced Truman that the Soviet leader failed to grasp the new weapon’s importance. This proved wrong. Stalin had maintained a great interest in the atomic bomb throughout, and he was kept abreast of the details by Soviet intelligence.

By the end of 1941, the Soviets were tracking American and British interest in developing an atomic bomb. They successfully infiltrated the project with spies, including Klaus Fuchs, who worked on the bomb at the Los Alamos laboratory. Stalin accessed details about the bomb, including its test schedule, almost as easily as did Truman. This helped enable the Soviets to test their own bomb by 1949.

9. Aldrich H. Ames

As a counterintelligence officer for the CIA who spied for the Soviet Union and, after its fall, for Russia, Aldrich H. Ames executed the costliest breach of security in agency history. He revealed over 100 covert operations and betrayed more than 30 spies working for the CIA and other Western intelligence services during his nine years of operation. Ames began spying in 1985 while he acted as the head of the CIA’s Soviet Counterintelligence Division. He received nearly $3 million for his efforts.

Ames provided the Soviets with information that compromised American espionage activities against the Soviets, including the details of a tunnel used by the CIA to tap communications to a space facility outside of Moscow. Ames came under suspicion when Soviet intelligence officers recruited by the FBI began disappearing in the late 1980s. Under surveillance, Ames made contact with a Russian handler, leading to his 1994 arrest. He is currently serving a life-sentence in a Federal penitentiary.

10. Adolf G. Tolkachev

The arrest of Aldrich H. Ames came too late to save the life of Adolf G. Tolkachev, a Soviet aviation specialist working on stealth technology for aircraft who volunteered his services as a spy to the CIA. Beginning in 1976 and continuing for nearly a decade, Tolkachev delivered intelligence about the plans, specifications and test results on existing and planned Soviet aircraft and missiles to his American handlers. Officials estimated that Tolkachev saved the United States billions of dollars in defense expenditures.

The KGB arrested Tolkachev in June 1985 and executed him in September of the following year. Exposed by a former CIA officer, Tolkachev’s spying received confirmation from documents provided to the Soviets by Aldrich H. Ames. Tolkachev’s work, however, continued to pay dividends to the United States, allowing its fighters deployed during the 1991 Gulf War to hold an edge over the Soviet warplanes in Saddam Hussein’s arsenal.