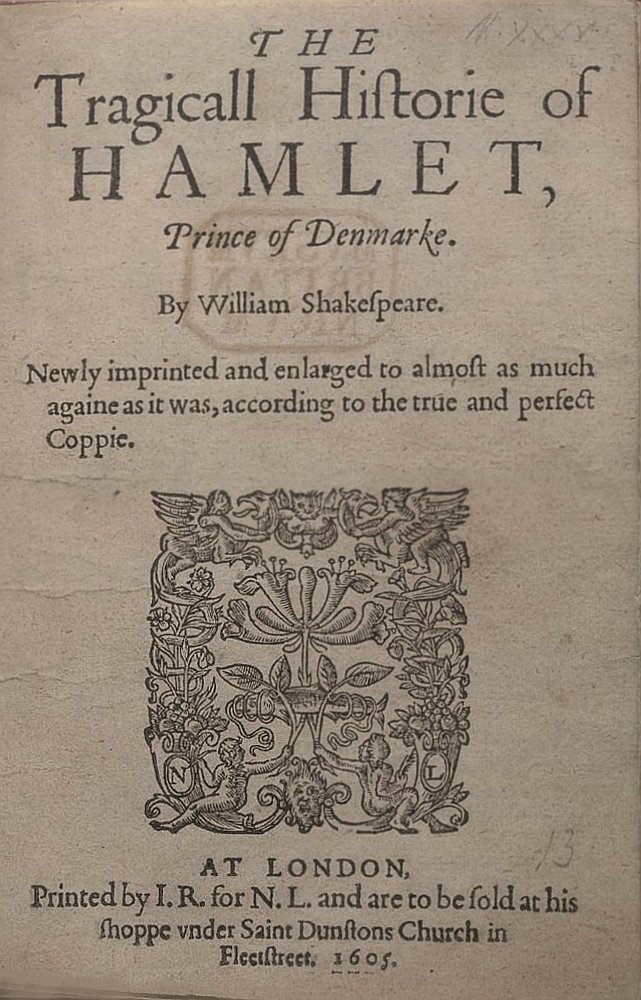

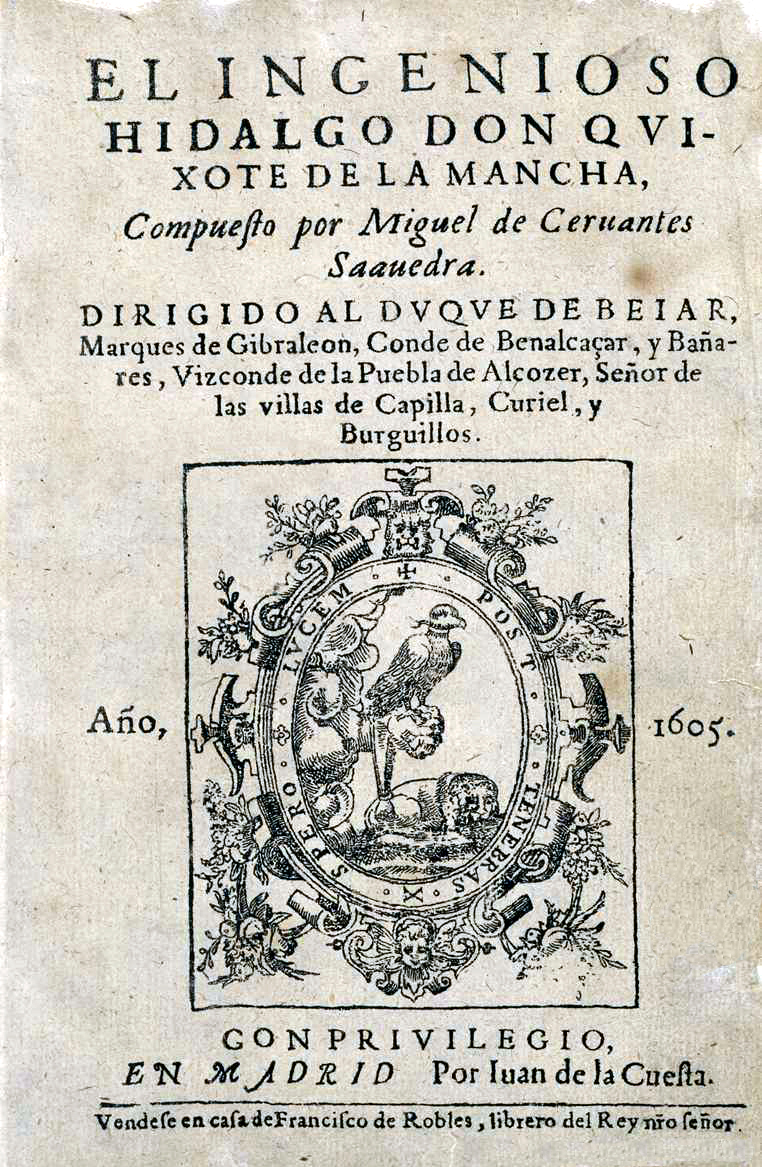

For a while it was thought that William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) died, like Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, on the very same day: April 23rd, 1616, four hundred years ago this month. In fact, England and Spain, the two superpowers at the time, one on its ascent, the other on the decline, followed different calendars, Julian and Gregorian, respectively. This means there was an interval of several days between those two April 23rds.

Still, the fact that these two magisterially influential Renaissance literary figures, one a playwright, the other a novelist, died almost simultaneously remains a coincidence full of symbolism.

They were kindred spirits. And today it is impossible to write in either English or Spanish without incurring a debt to them.

|  |

The two died never knowing the reach and influence of their work. Shakespeare didn’t care about seeing his plays in print. He saw himself as a man of the theater. It was only after his death that a couple of his acquaintances embarked on publishing the first Folios. Cervantes, in turn, died penniless. He had given away the rights of his novel to a printer. He was buried in a common grave.

Most profoundly, our modern sensibility is their brainchild. Prior to Shakespeare and Cervantes, literature—think of the Bible, the Iliad and Odyssey, the Divine Comedy and the Canterbury Tales—didn’t explore our inner emotional life. Instead, it dealt with types, archetypes, and prototypes.

Romeo and Juliet, King Lear and Hamlet, as well as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, in contrast, showed us how to be human. We empathize with them because they are characters plagued by contradictions, just like we are: they are caught between thought and action, they let their emotions carry them away, and they suffer from anxiety. The characters we find in Shakespeare and Cervantes speak directly to our modern selves.

There will be countless festivities around the world to commemorate 400 years since their deaths. Shakespeare’s Globe Theater started staging Hamlet in every single country in the world in 2014. Meanwhile, the Instituto Cervantes, devoted to promoting the Spanish language internationally, is sponsoring exhibits focused on the translations of Don Quixote. It is available in 58 different languages. In English alone there are at least a total of twenty versions.

|  |

For my part, this year I’m teaching a course called “Shakespeare in Prison,” at the Hampshire County Jail, in Northampton, Massachusetts. Half the class are the inside students and half are from the outside. Though the language has aged, I’m astonished by the degree to which these Elizabethan dramas are as urgent as ever for these students. Freedom is a major topic for the Bard, and the difference of interpretation depends on which side of the prison walls you’re in.

Freedom, of course, is the central concern of Don Quixote. In my view, no work of literature is more eloquent about this theme. I often tell my students about my fascination with the fact that Cervantes’ novel began to circulate in Madrid, in manuscript form, in 1604, meaning it was probably being written just as Shakespeare was shaping Hamlet, between 1599 and 1602.

In my imagination, I see the two drafting their work concurrently, in two languages that—miracle of miracles—coexist nowadays in various places, especially in the United States, where English and Spanish often step on each other’s’ toes among the close to 60 million Latinos.

As best as I can say, Cervantes didn’t know a thing about Shakespeare. Would he have liked The Bard? I’m not sure. We know that Shakespeare was indeed familiar with Don Quixote, at least to the degree of adapting a portion of it—the section called “The Ill-Fated Curiosity”—into a play called Cardenio, coauthored with his junior colleague John Fletcher. This, needless to say, doesn’t necessarily mean he liked the novel.

No matter. It is simply impossible to conceive the last four centuries without these two names: Shakespeare and Cervantes. We are their children.