In the early morning of 17 October 1945, workers in the federal capital and the province of Buenos Aires began marching toward the Plaza de Mayo and the Casa Rosada, the home of the executive branch. The military government did not anticipate the growing intensity of the public demonstration as the day carried on. The workers were there to stay until their demand was achieved: the release from military custody of Lieutenant General Juan Domingo Perón.

Juan Perón's supporters demanding his release in Plaza de Mayo on 17 October 1945.

The dramatic images of the descamisados, or shirtless ones, marching through the streets and hundreds of thousands of supporters clogging the plaza and the avenue connecting the Casa Rosada and the national Congress marked a consequential moment in Argentina’s sociopolitical history.

The political movement became known as Peronism and the Justicialist Party embodied it. Perón’s program “New Argentina,” advocating social justice, political sovereignty, and economic independence, called for nothing less than a total redefinition of the social compact.

Peronism permeated and penetrated all aspects of Argentine life, from the Church to the public schools, from the football pitch to the radio waves, becoming the hegemonic discourse through which supporters viewed their world and dissidents shaped their critiques.

Tramway car carrying descamisados in Buenos Aires on 17 Oct, 1945

Central to this movement’s endurance were political rituals, and the annual celebration marking 17 October, the future Day of Loyalty, would be its centerpiece.

The events of 17 October were the climax of a series of episodes that brought about the end of the military government and the ultimate election of Perón as president in January 1946.

On 9 October 1945, rivals within the armed forces demanded Perón resign from his positions as Vice President, Secretary of War, and Secretary of Labor and Social Security. He acquiesced, but on the condition he be able to give a farewell speech. The government abided, even agreeing to broadcast it on the official radio network.

The following day Perón delivered the speech from the balcony of the Secretariat of Labor and Welfare, which had come to be called the casa del pueblo, or house of the people.

The House of the People (Casa del Pueblo) in Buenos Aires was built in 1927, as the headquarters for the Socialist Party of Argentina (left). In 1953 it was ransacked by a Peronist mob (right). The building was demolished in 1974.

In his farewell address, Perón spoke as a civilian who was deeply committed to working-class struggles for social benefits. He detailed the accomplishments of his time as Secretary and confirmed that President Edelmiro Farrell had promised to guarantee all social benefits earned to date. Thus, further mass mobilization or civil unrest were unnecessary.

Still, it was clear Perón maintained ambitions. He declared “We shall win in a year, or we shall win in ten, but we shall win.” He concluded with what could only be interpreted as a warning, “I now request order, so we can go ahead in our triumphal march. But should it be necessary, someday I might request war.”

Military authorities arrested him four days later, imprisoning him on Isla Martín Garcia, a small island at the mouth of Uruguay River.

Perón’s arrest actually weakened the government, as he maintained many allies within it. The opposition and sectors of military bristled at this fact, with the former making even more strident demands. The military regime relented, declaring elections would be held in early 1946.

President Edelmiro Farrell (left) and the Vice President and Colonel Juan Perón, in April 1945.

Nevertheless, allies of Perón were either fired or arrested. The new Secretary of Labor and Welfare revealed President Farrell’s promises were empty while management refused to comply with Perón-era labor regulations. Unions across the country called for immediate mobilization and a general strike.

This moment proved critical for organized labor, as the General Confederation of Workers (CGT) met multiple times between 14 and 16 October to plot a path forward. The announcement by the military government that Perón was no longer under arrest, but rather in a military hospital in the capital, assuaged union leaders. Rank and file members, however, forced their hand. On 16 October, the CGT called for a general strike on the the 18th.

Peronist demonstration in the Plaza de Mayo during Perón's first term.

Supporters of Perón within and without organized labor decided not to wait even that long and took to the streets throughout the 17th. Spontaneous demonstrations were also held throughout the country, notably in La Plata, the capital of Buenos Aires province.

Military leaders believed that the masses swarming the Plaza de Mayo would quit as day turned to evening. They were wrong. The strike was so forceful that the de facto government gave in. The new Minister of War Eduardo Avalos agreed to meet with Perón, asking him to address the masses to help calm the situation.

At 11:10 p.m., Perón went out to a balcony of the Casa Rosada and gave a speech replete with promises of improvements and closing with a request for calm so that the workers there would return home peacefully.

Perón famously pronounced before a rapt and raucous crowd: “This is the people. This is the suffering people who represent the pain of the motherland, which we must reclaim. … This true celebration of democracy, represented by a people who march, now also, to ask their officials to fulfill their duty to reach the right of the true people.”

Perón cemented the connection between him and laborer, stating “From today I will feel a true Argentine pride because I interpret this collective movement as the rebirth of a workers’ conscience, which is the only thing that can make the country great and immortal.”

Finally, he pronounced that the following day – the day of the general strike – should be one of celebration and not protest. Workers, with Perón in the lead, were on the march.

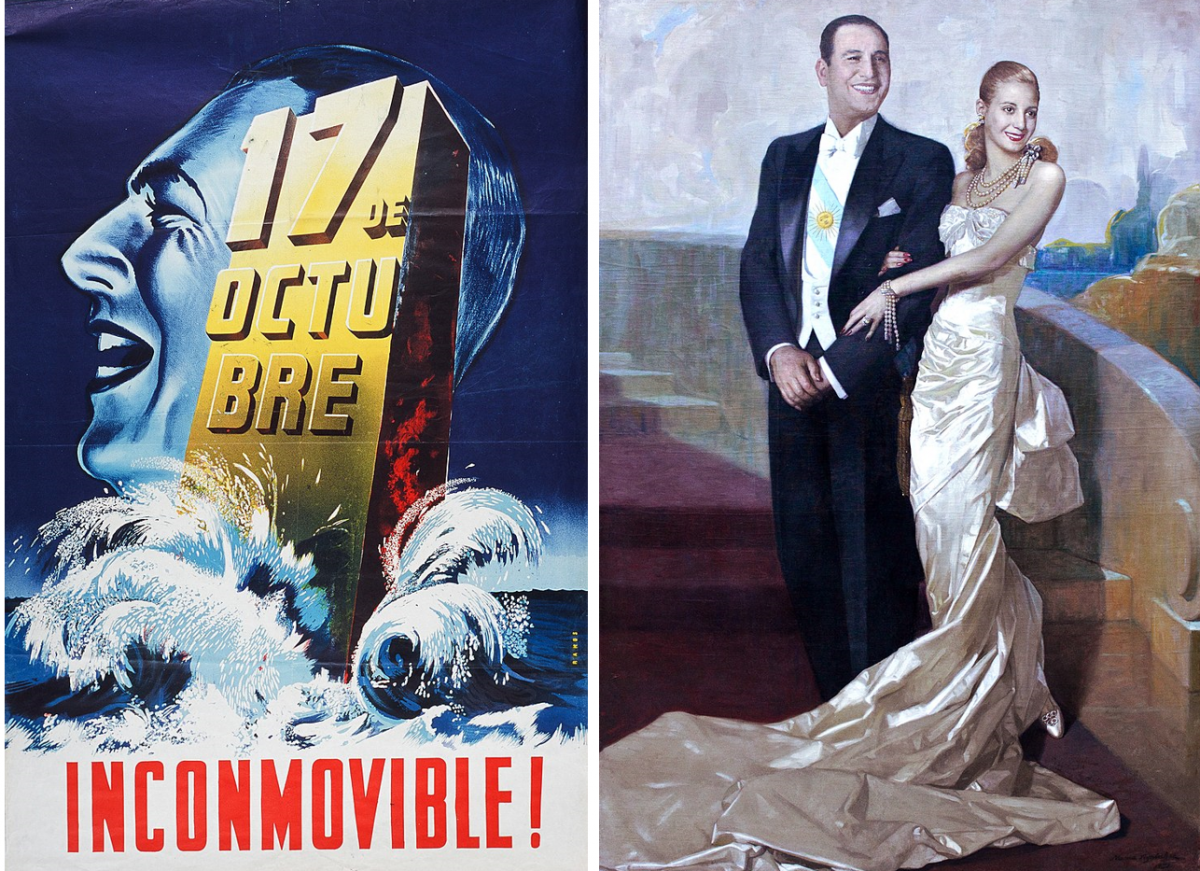

Propaganda poster commemorating the 2nd anniversary of the Day of Loyalty, in 1947 (left). Official portrait of Perón and his wife Eva (right).

But very quickly, the Peronist movement transformed these subversive and spontaneous acts of support for Perón into a ritualized day of loyalty. Perón and his acolytes made the so-called Day of Loyalty a national holiday in early October 1946. The movement to turn Peronism into a civic religion was afoot.

The 1951 celebration came in the wake of an attempted military putsch. Perón awarded medals to soldiers who beat back the attempted coup. The CGT, represented by laborers in work clothes, gave them CGT medals. These acts crystallized the conflation of the Peronist movement with the state.

The national holiday remained on the books until Perón’s overthrow in September 1955; it would surface again during Perón’s short-lived presidency from October 1973 to until his death in July 1974.

The day endures in the myth of Perón and the minds of Peronists. It is a reference point for generations of Argentines who bristled at the encroachment by workers and non-elites in public spaces. But even more so, it is a point of pride and inclusion for millions of Argentines who subscribe to the aspirations of Perón’s social democracy and the possibility of a world of dignified work and opportunity.

Want to Read More?

Mariano Ben Plotkin, Mañana es San Perón: A Cultural History of Perón's Argentina (2002).