As the 80th anniversary of the date that Prohibition was repealed—an annual event now affectionately dubbed Repeal Day—arrived on Dec. 5, I noticed that several of my friends raised a virtual glass on Facebook to celebrate their freedom to drink as they please. The repeal of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution ended an increasingly unpopular federal constraint on the production and sale of alcohol.

In truth, Prohibition had not ended drinking in America. It did curtail drinking, but historians disagree on the extent of the 18th Amendment’s contribution to health and sobriety. Certainly, it drove the market in spirits into illegal channels, increased graft and bribery, enriched the unscrupulous, and upped the chances that black-market beverages would be laced with poisonous additives like turpentine.

So my drinking friends on Repeal Day are hardly celebrating a simple freedom to drink; rather, they are celebrating the reinstated power and responsibility of state and local governments to regulate the production of alcohol and to profit from taxing it. In a sense, repeal also democratized the drinking that was happening anyway, since wealthier drinkers could afford to stockpile liquor before the 18th Amendment took effect and remained largely immune from prosecution.

I’m observing Repeal Day not by drinking—it’s a weekday, after all—but by briefly examining the regulatory history of our closest modern-day analog to Prohibition: the lingering illegality of marijuana sale and possession in most states. Following the legalization of marijuana in Colorado and Washington, the news media are now brimming with comparisons of alcohol to marijuana prohibition and “lessons learned” from the historic failure of the temperance movement to control America’s drinking habit.

In 1970, two legal scholars wrote a comparison of alcohol and marijuana law that I believe still offers some insight today. In “The Forbidden Fruit and the Tree of Knowledge: An Inquiry into the Legal History of American Marijuana Prohibition,” Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread observed that basic assumptions about the ill effects of marijuana use had persisted for 40 years without any significant reconsideration. This situation caused them two major concerns: “that the flagrant disregard for marijuana laws bespeaks a growing disenchantment with the capacity of our legal system to rationally order society, and that the assimilation of the marijuana issue into larger social conflicts has consigned the debate to the public viscera instead of the public mind.”

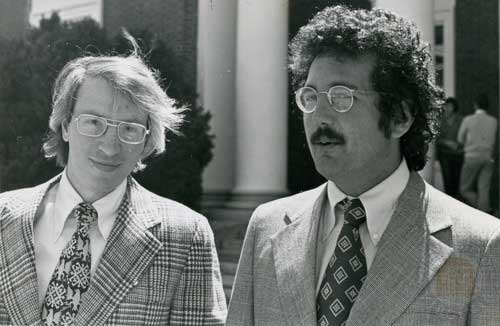

Richard Bonnie and Charles Whitebread. Photo: Records of the Virginia Law Weekly, Special Collections, University of Virginia Law Library

The authors wrote this before millions of Americans—a vastly disproportionate number of whom are young minority males—were incarcerated in state and federal prisons for possessing marijuana. Vast numbers of Americans do indeed disregard drug laws by smoking pot, but minorities consume at no greater rates than whites.

Bonnie and Whitebread wrote that the legal history of alcohol prohibition in the United States reflected a steady erosion of the idea that possession and use of intoxicating drinks in one’s home was a constitutionally guaranteed personal liberty. While judges had relied on this concept to rebuff late-1800s attempts to outlaw drinking, around the turn of the century the courts began to issue rulings granting state legislatures broader authority to exercise their police power in regard to alcohol.

The courts generally came to see the state legislatures as competent to decide whether drinking was a public evil and allowed the states to enact whatever laws they saw fit to curtail it. This turnaround coincided with the apex of the temperance movement, which in Bonnie and Whitebread’s eyes meant the judiciary had responded to public opinion rather than remaining disinterested interpreters of the law.

Marijuana prohibition, meanwhile, proceeded on an altogether different track. With the way cleared judicially for states to regulate personal use of intoxicants, marijuana seems to have been outlawed in a largely ad hoc manner, in an atmosphere of profound uncertainty about the drug’s effects. For one thing, legislators accepted the reasoning that marijuana should be outlawed preventively during Prohibition because otherwise, it would become a substitute intoxicant for the alcohol that could no longer legally be purchased.

Bonnie and Whitebread also believed the drug’s Mexican origins and reputed use by Mexicans, in conjunction with a hyperbolic media rendering of pot’s relationship to crime, spurred states to outlaw the drug. Especially as compared to alcohol prohibition, the legal framework for prohibiting marijuana was built largely out of the public eye.

The current climate of public opinion seems to be shifting in favor of treating marijuana like alcohol: as a legal, state-monitored intoxicant. Perhaps the law will again respond to public opinion, as Bonnie and Whitebread showed in the case of Prohibition repeal.

Just as repeal made it safe to drink whiskey through regulations that protected drinkers’ health, some now argue that legalizing and regulating marijuana will ensure that harmful additives and pesticides aren’t present and that users are informed of the levels of intoxicating chemicals in a given quantity of weed.

But most importantly, legalization would grant minority and low-income users the same freedom from fear of the police power already enjoyed by their wealthier, whiter counterparts.

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Government Smackdown: Federalism