December 7th marks the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Few place names in American history produce such a visceral response as the Hawaiian bay that housed the U.S. Pacific Fleet in 1941.

Aerial view of Pearl Harbor, October 1941.

The December 7 attack—the “date which will live in infamy”—is so deeply ingrained in the American psyche that it is almost always referred to as the Japanese “sneak” attack on Pearl Harbor. The inclusion of the adjective “sneak” underscores the duplicity of Japanese actions and portrays the Americans as victims of Japanese aggression, thereby validating the American response and outrage following the attack.

On this anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attacks, it is important not only to remember the attack, but also to examine the causes of the Japanese air raid and American and reaction to it.

That conflict between Japan and the United States came to the Pacific in late 1941 was of little surprise to any knowledgeable government or military official from either nation. Joseph Grew, the American ambassador to Japan since 1932, wrote to President Roosevelt in December, 1940 that it “seems to me increasingly clear that we [the U.S. and Japan] are bound to have a showdown someday, and the principle question at issue is whether it is to our advantage to have that showdown sooner or have it later.”

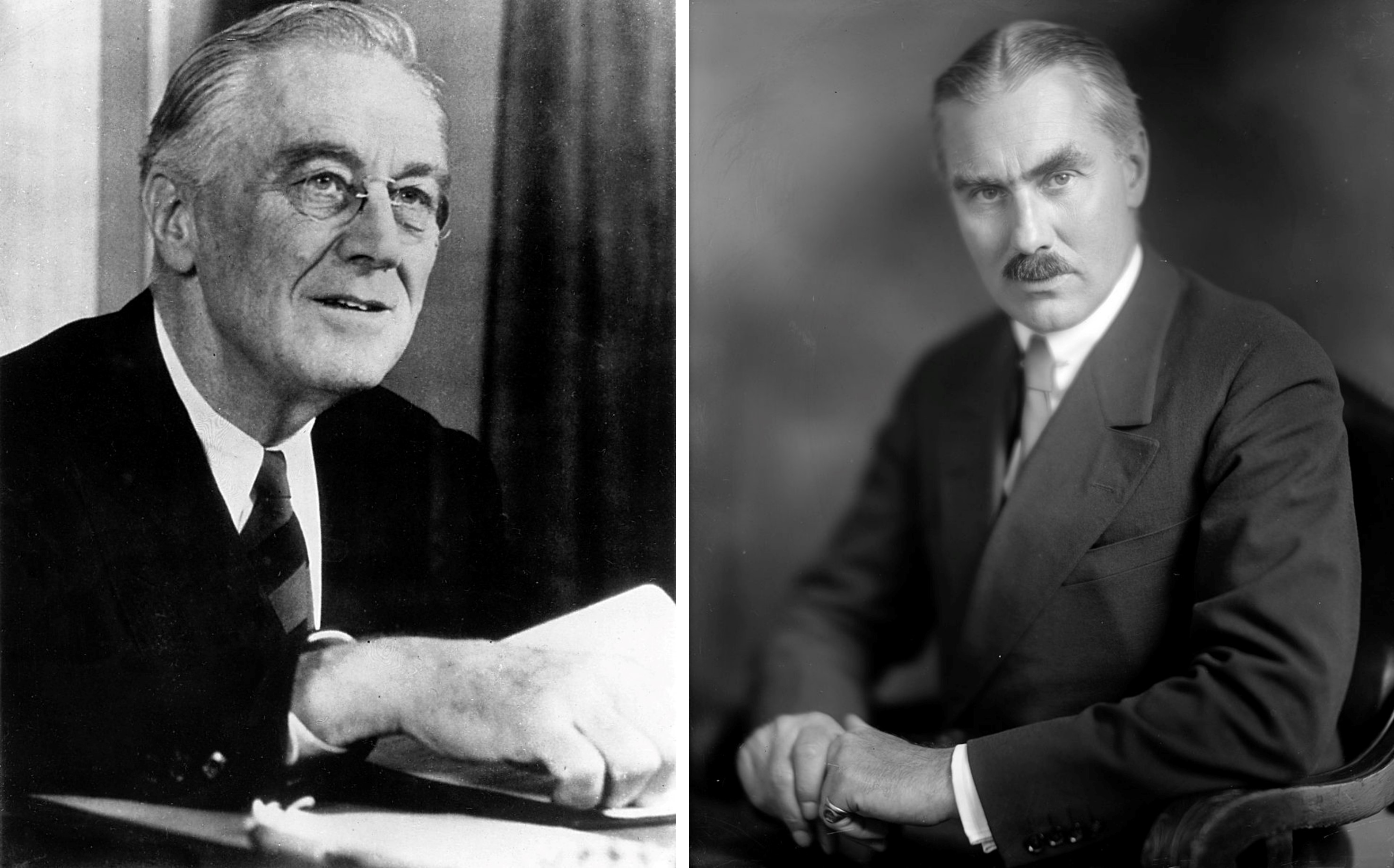

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left), and American Ambassador to Japan from 1905-1945, Joseph Grew (right).

The heightened tension between the two Pacific powers was the product of the rising tide of Japanese Imperialism in the 1930s.

While Japan had owned colonies for decades, by the late 1930s both the rate of acquisitions and the aggressive nature of Japanese imperials were increasing. The U.S. government openly condemned the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 but took no overt actions in response.

Over the next three years a series of “moral embargoes” enacted by the United States slowly started to choke off trade of vital war supplies to Japan, culminating in 1940 with embargoes on aviation fuel, scrap iron, and high grade steel. Japan responded in September of that year by signing the Tripartite Agreement with Germany and Italy to pressure the United States to back down.

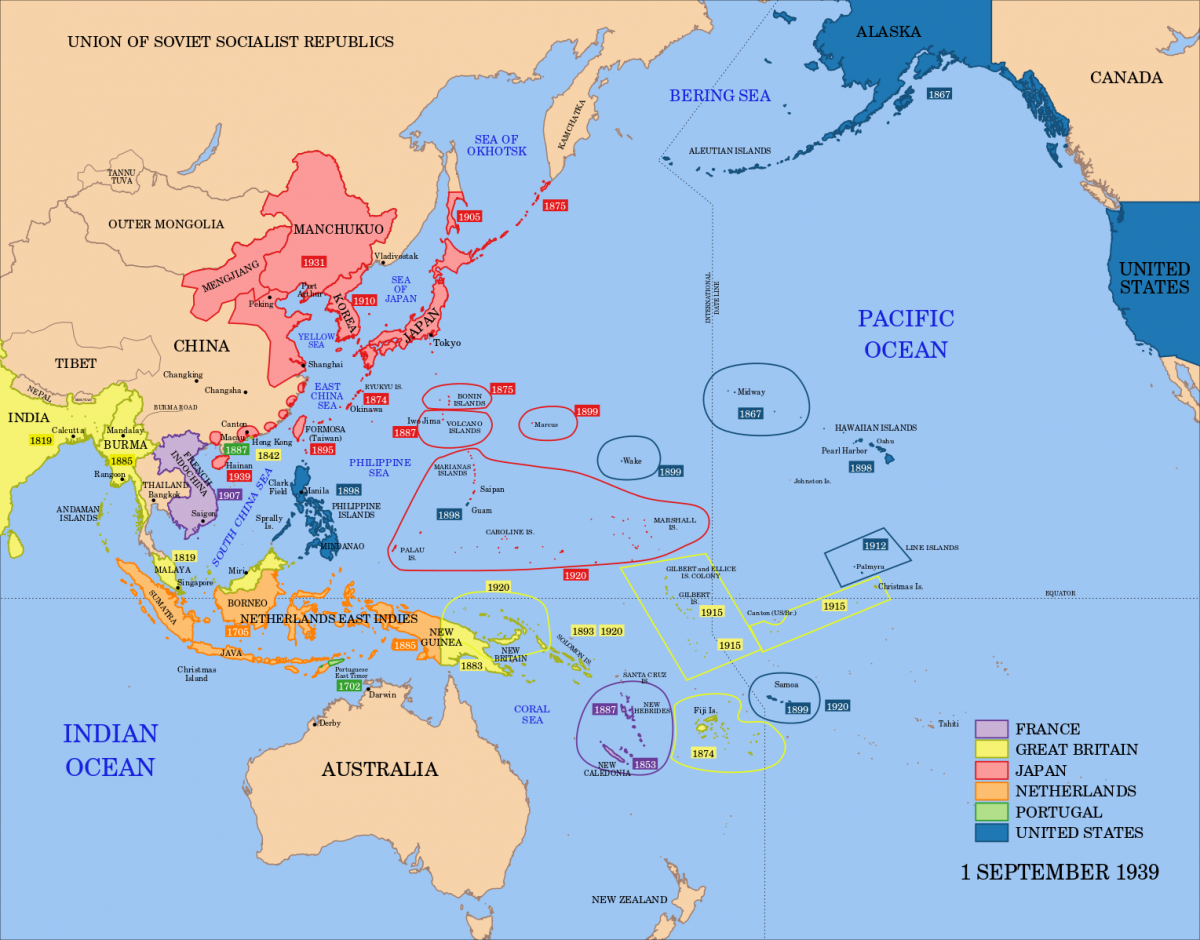

Map of Pacific imperial influences, 1939.

Tensions continued to build between the two nations. In March, 1941 President Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act, which authorized the sale of weapons to Japan’s colonial rival Britain. In April, the Japanese signed the Japan-Soviet Neutrality Pact, eliminating a potential enemy and freeing military forces for offensive action elsewhere in the Pacific. Later in the spring the U.S. Pacific fleet relocated from the west coast to Pearl Harbor in an attempt to dissuade Japanese aggression.

In July, the Japanese then moved south into French Indochina. America and Britain responded with a full oil embargo. Without oil, the Japanese would have no choice but to temper their aggression in Asia or face the prospect of running out of fuel by 1942. Left with little choice, the Japanese finalized their decision to go to war in September 1941.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was only a means to an end for Japan. The primary objective of the 1941/42 Centrifugal Offensive was the Dutch East Indies and its rich oil fields that could make Japan independent for its energy needs. But an attack south towards the East Indies required securing the sea lanes, which in turn required seizing Malay and the Philippines and by extension starting a war with Britain and the United States.

Japanese military planners knew they could not win a long fight with America; its industrial and economic might would eventually prevail.

The solution was obvious. Japan needed to fight and win a quick war. Believing the people of the United States to be unwilling to prosecute a long, bloody war over distant colonial possessions, Japanese planners envisioned a defensive war that would drain American resolve.

If the initial attacks could defeat available British and American forces and buy a window of opportunity, the Japanese fleet could seize key islands across the Pacific and establish a defensive cordon. American attacks sent to relieve the Philippines or attack the cordon could be met and destroyed in a series of climatic battles in which the Japanese would prevail. After a few serious defeats, American resolve would crumble, and the war would end with Japan owning the key oil fields it so desperately needed.

It was a long shot, but it was the best hope the Japanese had at defeating the Americans. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack, gloomily evaluated Japanese chances for success when he declared to the Japanese prime minister, “In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain I will run wild and win victory upon victory. But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success.”

Thus, with the objective of destroying the American offensive capability in the Pacific to enable Japanese aggression elsewhere as its primary goal, a Japanese strike force with six aircraft carriers as its core departed Japan. In the early morning hours of December 7 almost two hundred aircraft—fully half of the embarked planes on the carriers—took off towards Hawaii.

Arriving over the target at approximately 7:43 AM, the dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and fighters of the strike force set about attacking the unsuspecting American ships. Anchored throughout the bay, devoid of protective torpedo nets, without combat watches on duty, and lacking accessible ammunition, the American ships were easy prey.

The Japanese pilots’ primary targets, the American aircraft carriers, were not present, necessitating a shift to their secondary target, the American battleships. The lead attack crippled the capital ships, most notably the battleship Arizona which was broken in two when a bomb penetrated to its magazine and killed more than 1500 hundred of her crew members.

USS Arizona in New York, 1916 (above), and the Arizona after the attack at Pearl Harbor, 1941 (below).

The second wave arrived about an hour after the first and targeted the airfields scattered around the bay. Airmen at Hickam Field and on Ford Island tried desperately to get their planes airborne, but reports indicate that fewer than ten succeeded. The American response to both waves, be it ground based anti-aircraft fire or airborne fighters, was completely ineffectual. All told the Japanese lost forty-nine aircraft.

By 10:00 AM the attacks were over. The Americans lost heavily in the attack. Eight battleships were sunk or severely damaged, along with three cruisers, three destroyers, almost two hundred aircraft. In all, over 3500 military personnel were killed or wounded.

USS Shaw explodes during attack at Pearl Harbor.

Most importantly for the Japanese, their attack succeeded in its design to cripple the American ability to respond to its offensive against the Dutch East Indies.

The shock waves of Pearl Harbor reverberated throughout the struggle raging in Europe. In Britain, having long stood in opposition to Hitler’s Germany, Winston Churchill greeted the news with joy knowing that American might was now in the war effort. He was “saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, [and] went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.”

In Germany, Hitler interpreted the results differently. Joyful at the losses the Americans suffered, he remarked “We can’t lose the war at all. We now have an ally which has never been conquered in 3,000 years.” Four days later, on December 11, Germany declared war on the United States.

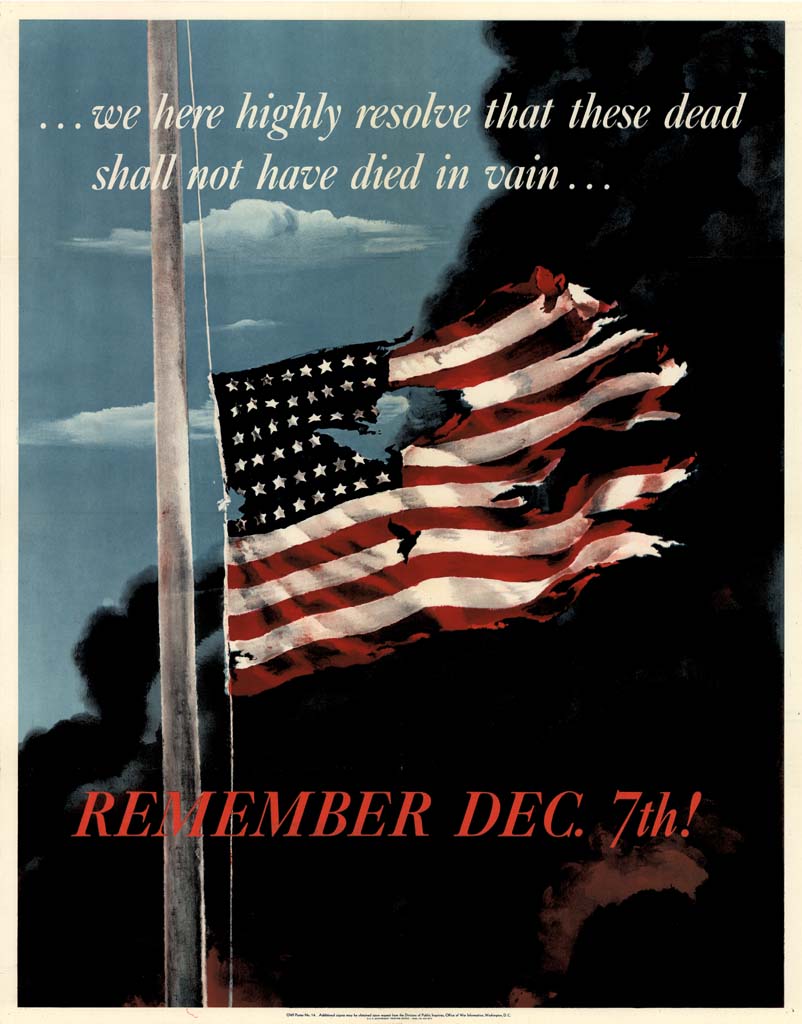

"Remember Dec. 7th!" World War II poster.

In the United States, the bombing ignited a passion that President Roosevelt had for years sought to spark. Long weary of the worsening geopolitical situation and German and Japanese aggression, Roosevelt had made efforts to prepare America for war and support Britain and the Soviet Union throughout 1940 and 1941.

Fighting isolationist sentiments, Roosevelt lamented his inability to do more prior to the attack. The Japanese solved his problem with their assault on Pearl Harbor. On December 8, the Senate voted 82-0 to declare war. The House voted 388-1. The ensuing mobilization of American manpower and resources stands unparalleled in U.S. history.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was not an entirely unprovoked attack, nor was it a complete surprise. American leaders rightfully sought to temper the illegal Japanese wars in Asia by utilizing economic sanctions, but in so doing forced the Japanese to either abandon their gains (something that was completely unrealistic) or launch the long-brewing conflict between the two nations.

Wreaths at USS Arizona Memorial, 2008.

In the end, the infamy and tragedy of Pearl Harbor was a result of the American overestimation of the ability of embargoes to temper Japan’s strategic designs, and a Japanese underestimation of American resolve to respond to aggression.