One hundred fifty years ago this month, Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) started publishing his novel Crime and Punishment in installments in the Moscow journal The Russian Herald.

|

The novel appeared monthly over the course of 1866, and it was a smash hit. As one influential critic put it at the time:

During the year 1866 only Crime and Punishment was being read, only it was being spoken about by fans of literature, who often complained about the stifling power of the novel and the painful impression it left which caused people with strong nerves to risk illness and forced those with weak nerves to give up reading it altogether.

What caused this novel to take Russia by storm?

Russian society at the time was struck by the boldness of Dostoevsky’s idea. For some critics, the murders of pawnbroker Alyona Ivanovna and her sister Lizaveta committed by ex-student Rodion Raskolnikov were “the purest absurdity.” But others immediately began to see coincidence with current events.

After all, on January 12, 1866, just days after the first installment of Crime and Punishment was published, a student by the name of Danilov committed a similar crime: killing a moneylender and his servant and robbing their apartment. In the wake of this event, Dostoevsky’s detailed description of how the violent crime was plotted seemed prescient.

Literary critic Nikolai Strakhov maintained that the public believed Danilov’s crime to be related to “the general nihilistic conviction that all means were permitted to improve an unreasonable state of affairs,” a conviction shared by Dostoevsky’s central hero, Raskolnikov.

What was that “unreasonable state of affairs”?

Among other things, young radicals believed that in the wake of the emancipation of the Russian serfs in 1861, the peasantry should have risen up against the tsarist autocracy. Imagining that the Russian people might embody the socialist principles radicals espoused, they expected further social changes and dreamed of a humanitarian society to replace the status quo.

|

Other radicals thought that the answer to Russian woes was the development of capitalism and further industrialization, led—it was to be hoped—by enlightened members of the intelligentsia in the direction of economic (and social) progress for all.

Some of these radical youth called themselves “nihilists” and preached a need to overturn society. Though the aim of many of their ideas was altruistic and humanitarian—a desire to alleviate human suffering and to distribute wealth and opportunities among a larger swath of the population—the results were sometimes violent.

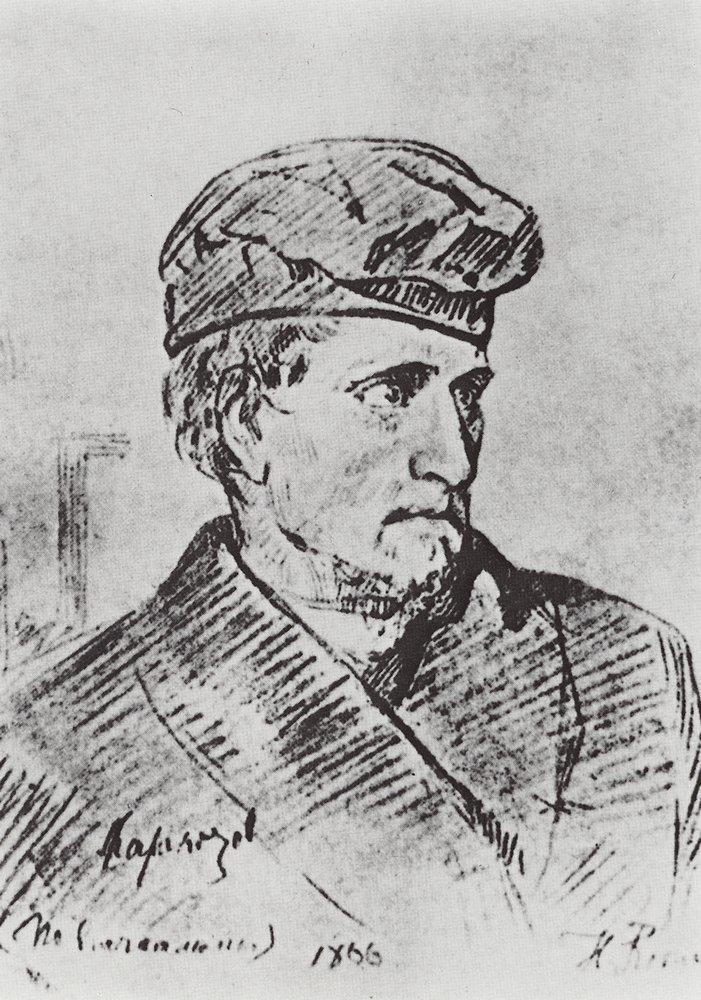

And these violent methods were clearly on display on April 4, 1866, when a young student named Dmitri Karakozov took a shot at Tsar Alexander II.

Dostoevsky himself was shocked and horrified at this turn of events—midway through the writing and publication of his tremendously successful novel—almost as much by his fear of government reprisals as by his disbelief that a Russian would raise his hand against the autocrat.

Dostoevsky intended the novel more than anything to be about human happiness, certainly not as a fictional take on current events.

As he wrote in his notebook: “man is not born for happiness. Man earns his happiness, and always by suffering,” which for him corresponded to the definition of Orthodox Christianity. In other words, in the novel readers watch as the central character, a lapsed Christian, commits a crime, suffers for having done it, and then is redeemed and given the chance for happiness through that very suffering.

For Raskolnikov his misdeeds are as much against god and man as they are against society and the law, which is one reason the novel remains a staple for young readers. The youth of the young radical was essential for Dostoevsky’s conception of his protagonist too. As he jotted to himself in his notebook: “In writing [the novel], do not forget that he is 23 years old.”

|

| New Dostoevsky monument in St. Petersburg (Photo by author, 2015) |

Crime and Punishment may be a thriller, but it is not a whodunit. Instead, the plot centers around a young man who is frustrated with the social and financial opportunities available to him, a young man who believes he can and should seize his own destiny.

Written by a self-made man whose own life up to this point had been full of trauma—from a near-execution and sentence served in Siberia for anti-government agitation to publishing aspirations blocked by government censorship and ensuing poverty—the novel offers a path to redemption for the criminal and the sinner.

With the historical events of 1866 now long forgotten by most readers, Crime and Punishment stands as a novel of ideas, in which philosophies of life are incarnated in various characters. The novel interrogates the right of man to violate social norms and conventions and to choose his own path in life regardless of his social status.

For Dostoevsky, it was a “psychological account of a crime.” But for Russians one hundred and fifty years ago, it felt almost like journalism—an account of an unhinged student who commits acts of terrorism.