The War of the Pacific (1879-1884), which pitted Chile against the allied forces of Peru and Bolivia, had a profound, long-lasting impact on the geopolitical balance of South America.

The conflict resulted in a clear victory for Chile: the once diffuse borderlands among these countries were redrawn in favor of a suddenly enlarged Chile; Bolivia lost its nitrate-rich coastal region and became a land-locked state; while Peru also lost valuable land and saw its capital invaded and administered by Chilean forces for more than two years.

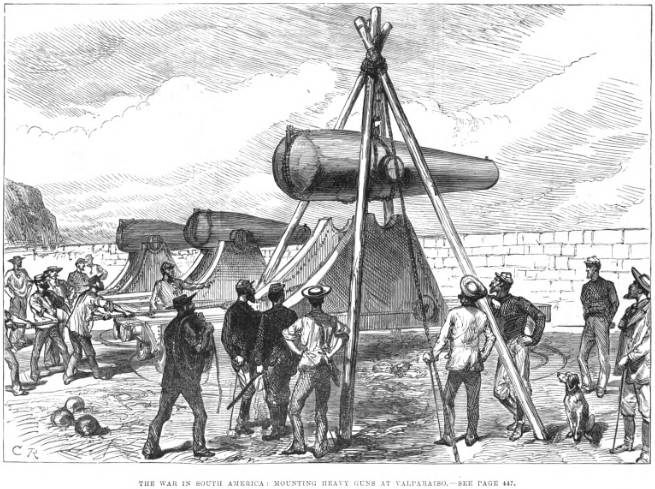

At stake were nitrate and other mineral deposits in the Atacama Desert, control of the Pacific trade routes, and the demarcation of national borders. Previous military conflicts in the region were directly related to these issues, such as the War of the Confederation (1836-1839) and the Spanish-South American War (1864-1866).

Initially, nitrate was largely exploited in the Peruvian Tarapacá region, but, in the 1860s, mining activity expanded to the Bolivian Atacama region, mainly led by Chilean and British companies. The mineral was used both as a fertilizer and in the manufacture of explosives, making it one of the most coveted products in international trade and industry.

This economic activity caused profound demographic changes.

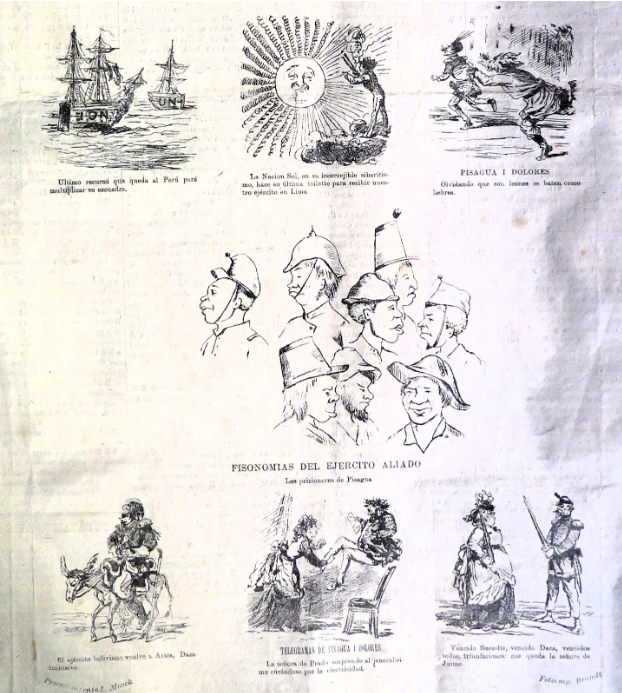

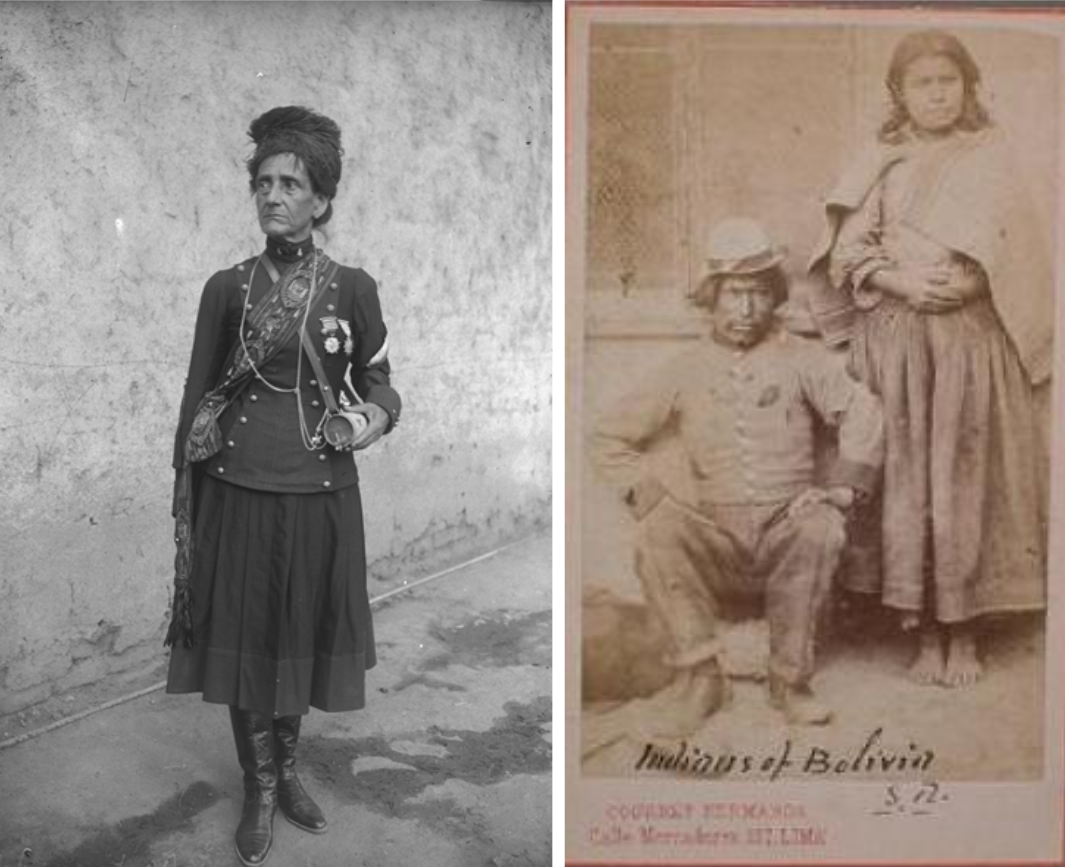

Large numbers of Chilean workers moved to the area, eventually outnumbering Bolivian workers. Peru, for its part, passed a law in 1849 that brought thousands of Chinese workers to labor in guano extraction and sugar plantations, forcing them into slave-like conditions and subjecting them to discrimination for decades to come. Though usually overlooked in claims of Hispanization, Indigenous communities were also robust, adding Cunza, Aymara, and Quechua to the linguistic diversity of the area.

The international economic recession of the 1870s hit the region hard and increased Chilean expansionist pressures, but the immediate trigger for the conflict was Bolivia’s 1878 tax increase on foreign companies extracting nitrate from its territories (an increase that was also intended to help them rebuild after the devastating earthquake and tsunami that hit Iquique in 1877).

The Antofagasta Nitrate and Railway Company, a Chilean-British company, refused to pay this increase, which was in violation of their privileges under an 1874 treaty.

After negotiations failed, the Bolivian government tried to expropriate the company’s assets and auction them off, but on the day of the auction, February 14, 1879, Chilean troops invaded Antofagasta.

Soon after, Bolivia declared war on Chile. With a secret 1873 alliance with Bolivia and its interests also at stake, Peru joined Bolivia after mediation efforts failed. On April 5, 1879, Chile officially declared war on both Bolivia and Peru.

The societies involved were mobilized to an unprecedented degree, making this conflict a defining event in the construction of their national identities. The press fueled nationalist sentiments with an aggressive and soon racist portrayal of the enemies.

Women participated in the war effort at almost every level. On the home front, they organized charitable societies to raise money and other resources, and provide support for the wounded, and, later, veterans. At the war front, the “cantineras” (Chile) and “rabonas” (allied forces) played a key role, delivering water, food, and ammunition, aiding the wounded, and even taking up arms to fight.

The end of the war came in stages.

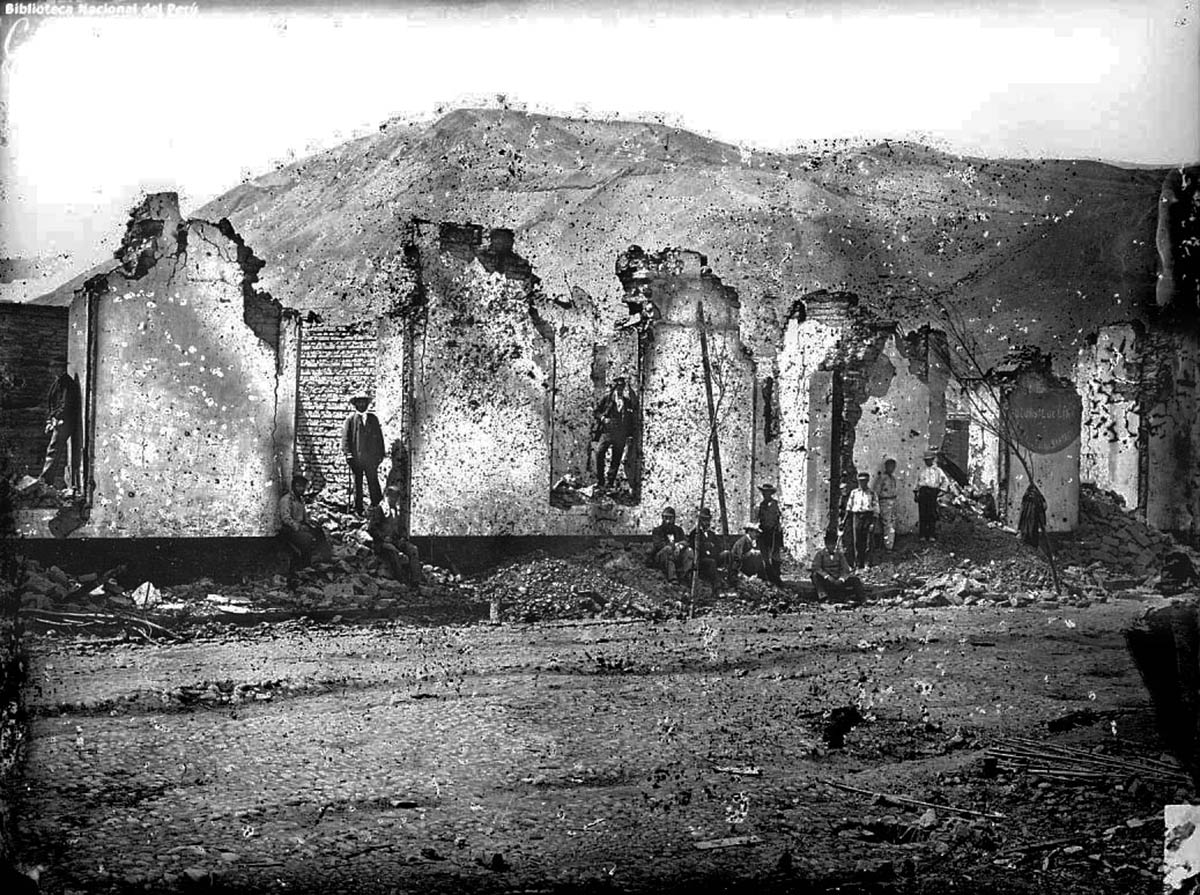

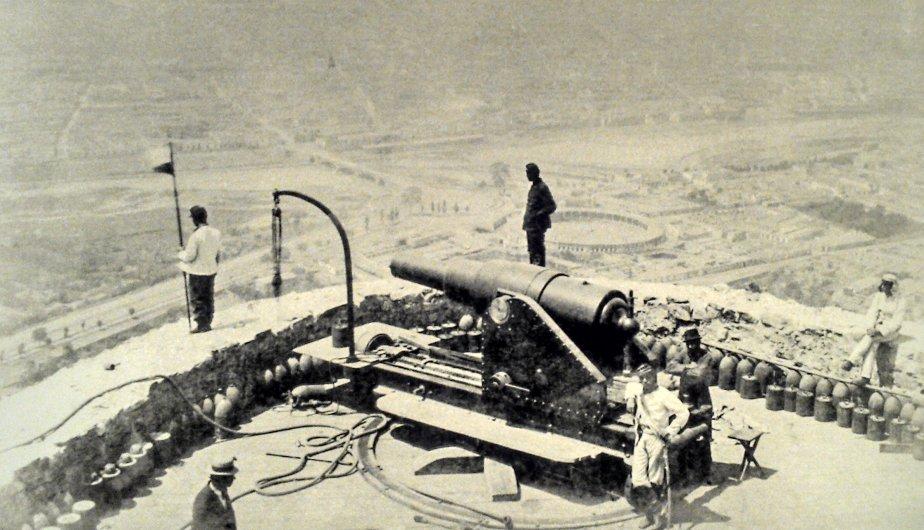

After the brutal battles of San Juan and Chorrillos (January 13, 1881) and Miraflores (January 15, 1881), Chilean forces occupied the city of Lima. Photographs of the Chilean flag flying over the Peruvian capital attest to the political significance of this occupation and the looting of the city.

The Peruvian army lost nearly a third of its forces, and Chile considered the war virtually won. As a result, its military forces resumed more intensive operations against Indigenous Mapuche resistance to Chilean campaigns in their territory.

Although the Peruvian army was greatly reduced, however, the resistance continued in the form of guerrillas and montoneras. Fighting these more elusive forces proved challenging for the Chilean army and prolonged the conflict for more than two years. In 1883, the last pockets of resistance were defeated, and Chile and Peru signed a peace treaty (Treaty of Ancon, October 22, 1883).

The treaty granted Chile the department of Tarapacá and placed the department of Arica under its temporary control. It also set a ten-year deadline for a plebiscite to allow the local population to decide the nation to which they preferred to belong. The plebiscite never took place, and after lengthy negotiations it was decided to divide the disputed territory in two (Treaty of Lima, 1929). Arica became definitively Chilean and Tacna returned to Peruvian sovereignty.

Meanwhile, Bolivia had abandoned military action after its defeat at the Battle of Tacna (May 26, 1880) and concentrated on diplomatic action. A truce was signed on April 4, 1884, officially ending the War of the Pacific (as the last Chilean troops also left Lima). However, it was not until the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1904 that Bolivia and Chile normalized relations.

Tensions persist to this day, however. In 2009, Bolivia’s new constitution reaffirmed the country’s “inalienable and indefeasible right over the territory that gives it access to the Pacific Ocean and its maritime space” (Article 267). In 2013, Bolivia filed a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague to force Chile to negotiate Bolivia’s access to the sea. In 2018, the ICJ ruled that Chile was under no obligation to enter negotiations over sovereign sea access.

Chile benefited greatly from these geopolitical changes It incorporated the mineral-rich territories of Antofagasta, Tarapacá, and Tacna-Arica (Tacna returned to Peru in 1929).

The territorial expansion of Chile was also catapulted at that time by the invasion of Indigenous territories in the so-called “Pacification of Araucanía.” With these concurrent expansions, Chile gained approximately two-thirds of its current size.

For its inhabitants, however, the mineral wealth of this region continues to be a curse, causing ecological exhaustion. Lithium reserves here and in neighboring areas of Bolivia and Argentina are among the largest in the world.

The water-intensive extraction of lithium depletes water resources in an already water stressed area, resulting in drying rivers and wetlands, damaged ecosystems, limited access to water, suffering crops and livestock, and local communities trying to fight multinational mining corporations that, for the most part, have the support of local and national governments.