“As a City on a Hill.” Depending on your temperament you find the phrase inspirational or empty. Either way you know it because it is so familiar, as woven into the very fabric of the American idea as “we the people” and “all men are created equal.”

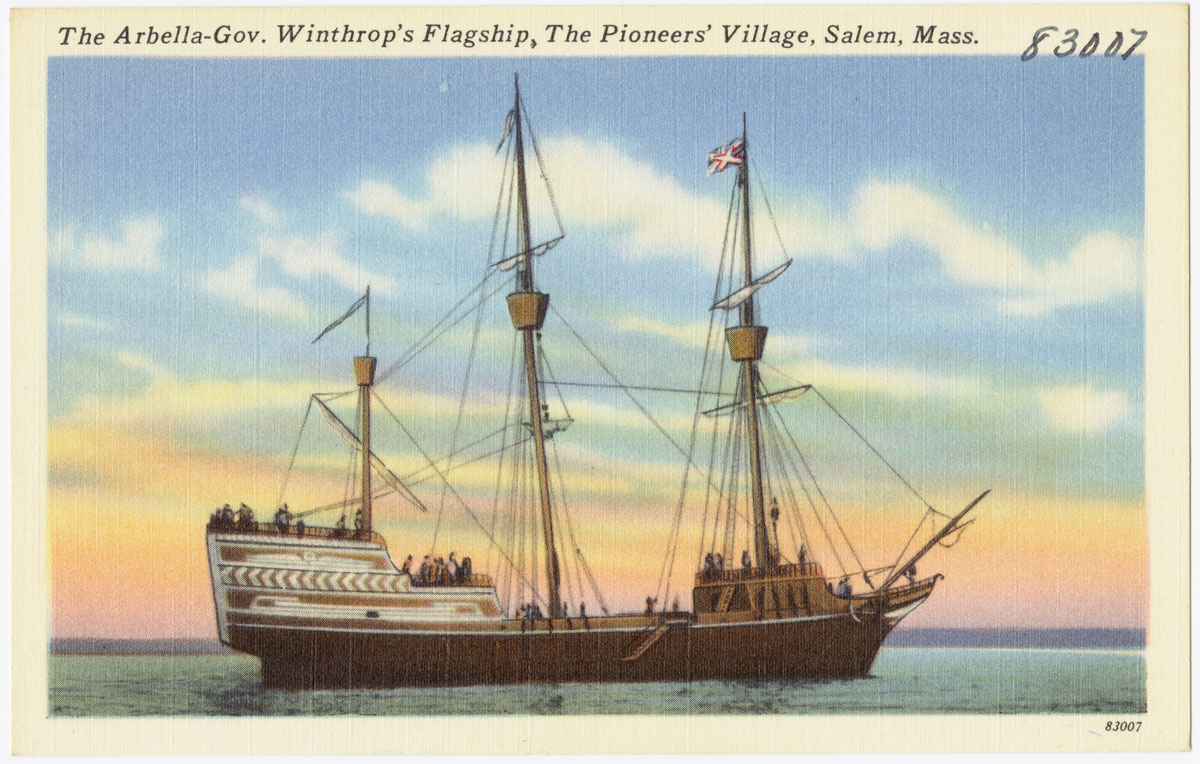

The story goes like this: In 1630, as a brave and beleaguered collection of English Puritans ventured to their destiny on the tiny ship Arbella, their leader John Winthrop delivered a soul-stirring sermon in which he invoked that biblical vision to steel his shipmates and give the whole enterprise a providential purpose. That scene is part of the American origin story, central to our national creed.

Except that it isn’t. As Daniel Rodgers summarizes: “Most of this is a modern invention and much of it is wrong.”

With that shot across the bow, Rodgers proceeds in a series of short but masterful chapters to trace the history of the phrase—and “A Model of Christian Charity,” the larger “sermon” from which it came—in American culture from the 17th century to the present.

This postcard depicts a recreation of the Arbella, the ship that carried John Winthrop and his fellow Puritans to present-day Massachusetts.

Without being glib about it, much of what he finds is not very much. “A Model of Christian Charity” was written as part of the political and religious debates swirling in the world of Reformation England. It doesn’t really envision a future utopian experiment across the Atlantic. Further, there is actually no evidence that Winthrop’s fellow passengers heard (or read) the essay as they made their way across the ocean. For his part, Winthrop never used the phrase “city on a hill” again.

Besides, divine purpose was not the exclusive domain of the Puritans. Lots of other settlers across the North American continent in the 17th and 18th centuries saw themselves as “Chosen People” too, enacting their own holy experiments. Perhaps foremost among those, if we are looking for American origin stories, was William Penn’s Philadelphia. Quaker Philadelphia, it has always seemed to me, foreshadows what the United States would become more than the Puritan outpost of Boston. After all, Thomas Jefferson called Penn “the greatest law-giver the world has produced.” He never mentioned Winthrop.

Jefferson was not alone among the Founders who ignored, or simply did not know, Winthrop’s “Model of Christian Charity.” The essay—I call it that because as Rodgers notes applying the term “sermon” is problematic—did not circulate, was not re-printed, and seems not to have influenced the debates over independence or the Constitution. Whatever else they thought they were creating when the Founders shaped a constitutional republic, it was not a city on a hill.

The Winthrop Fleet, which was funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company, came ashore in 1630.

Ditto across the 19th century, even as Americans shaped and re-shaped the meaning of the nation. In a particularly splendid chapter, Rodgers describes the single instance when the phrase “city on a hill” had real resonance and ironically, it was back across the Atlantic. The former slaves who founded the nation of Liberia invoked the phrase “with particular exuberance.” In fact, Rodgers has discovered, “for three centuries after its writing. . .‘A Model of Christian Charity’ lay out of sight, virtually invisible as a cultural reference point.”

Add 300 to 1630 and we arrive in the 1930s. At that point, “A Model of Christian Charity” began to escape the history books. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that the essay, and New England more broadly, was moved from the periphery of the American story and toward its center.

The key figure here is Harvard professor Perry Miller. In his magisterial work The New England Mind, Miller took Puritanism seriously as a set of ideas—complicated, complex, and in many ways distant from us today—but worth reckoning with nonetheless. As part of that project, Miller brought “A Model of Christian Charity” out of obscurity and into the scholarly conversation.

From Miller to University of Chicago historian Daniel Boorstin and Yale historian Edmund Morgan to President John F. Kennedy, Winthrop’s “A Model of Christian Charity” found a new life in Cold War America. And with Kennedy, the “city on a hill” metaphor jumped from the academic world into the political discourse. Once the phrase became part of the civil religion, no one made more use of it than Ronald Reagan.

Reagan first invoked the “city” as governor of California in 1969-70 and once he started using the phrase he couldn’t stop, first on the campaign trail and then as president, even if his speech writer Anthony Dolan confused John Winthrop with Joseph Warren, who then became “Joseph” Winthrop.

Today, of course, you can’t run for any office without working the “city on a hill” into a stump speech. If it has started to feel a bit clichéd, then Rodgers adroitly demonstrates that in moving into popular usage the “city on a hill” and “A Model of Christian Charity” have been extraordinarily simplified.

Beyond the now-remote theology in the essay, much of it—as its very title suggests—is about the necessity of mutual obligation. “We must love brotherly without dissimulation,” Winthrop wrote, “We must not look on our own things, but also on the things of our brethren.” That bit has been forgotten by those who have tossed Winthrop’s memory around so loosely.

Simplified and clichéd, Winthrop’s phrase has become central to a certain conception of American “exceptionalism,” a vague and vaporous idea that the United States has pursued a divine errand into the wilderness and thus occupies a singular place among nations.

In his delightful As a City on a Hill, Rodgers has demonstrated that Winthrop’s words simply do not and cannot bear the ponderous weight they have been asked to bear. Here’s hoping that some of those exceptionalists will read this book and let Winthrop rest in peace.