In this moment of intense political polarization Arizona State University History Professor Donald Critchlow takes readers back to an earlier era of political contention and party identity crisis. Republican Character: From Nixon to Reagan provides a concise, insightful study of presidential candidates and their styles of political decision making. These styles range from the principled to the pragmatic.

Republican Character examines the lives and political careers of four figures central to the Republican Party in the post-Eisenhower years: Richard Nixon, Nelson Rockefeller, Barry Goldwater, and Ronald Reagan. Republican Character differs from most political works by focusing on "virtue" instead of policy. Written with a broad audience in mind, Critchlow utilizes biographies and intertwined histories to argue that "principled pragmatism, the ability to compromise while maintaining core principles, is essential to political success" (10).

Republican Character's structure tracks an ascension of "character," starting with Nixon whose disposition Critchlow sees as the least inclined to political success. Each subsequent figure's character is temperamentally better than the last's. This format is essential, as Critchlow maintains that "Nixon, Rockefeller and Goldwater possessed temperamental flaws... that proved destructive to fulfilling their ambition" and that it was Reagan's temperament which helped him "gain his party's nomination, win the election, and govern successfully" (1). The breadth of sources utilized, from biographies to personal correspondences to congressional hearings, gives readers a glimpse into the lives of these men and the character traits that defined them.

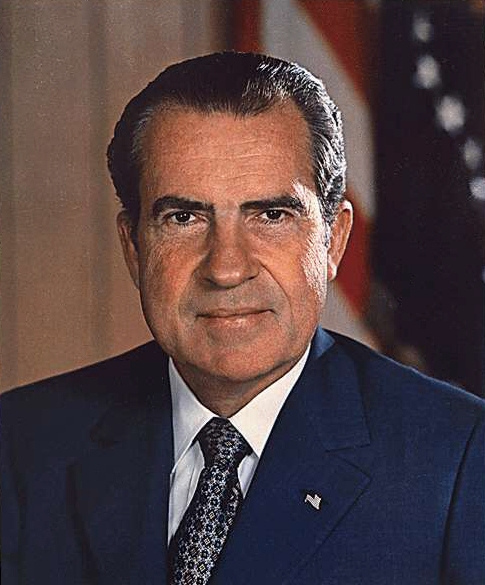

Chapter One examines Richard Nixon and the complex story of a man remembered for the naked, amoral ambition that ultimately ended his political career. In his early political career Critchlow believes that Nixon sought to better American society and the world. Nixon hardened over the years, after the press gave him the moniker of "Tricky Dicky" in the wake of his losses in 1960 and 1962, and after mounting intra-party slights. Consequently, by the 1968 campaign, the once principled man was no more, as "idealism appeared to give way to opportunism, political adroitness to self-advancement, and idealism to cynicism" (37).

Critchlow next looks at Nelson Rockefeller, the one man among the four never nominated for the presidency. Rockefeller was hampered by his belief that "if voters would come to their senses and see what he had to offer the country, the party and the nation would be saved" (39). His arrogance did not do him any favors nor did his liberal record as governor of New York: coupled, they made his occasional conservatism appear disingenuous. His conceit and poor electoral timing led to consistent shortcomings on the national stage.

Critchlow compares Nixon and Rockefeller in his chapter entitled "Idealism Betrayed, Opportunity Denied, Nixon and Rockefeller Compared." These men were "political rivals driven more by ambition and the desire for power than by principle, although this is not to say they lacked totally in principle" (63). Nixon and Rockefeller crossed paths on numerous occasions, and Rockefeller turned down Nixon's Vice-Presidential offer in 1960. These men's moderate to liberal Republican positions forced them to be ideologically flexible, but their respective characters hampered their success.

Republican Character returns to its biographical vignettes in "Barry Goldwater: Undisciplined Individualist." Much of Goldwater's career was defined by loyalty to his brand of conservatism and to the Republican Party. Goldwater's greatest flaw was not his ideology, but rather his unrepentant brashness and his "fire from the hip" mentality (103). The public continued to view him as an extremist. His associations with fringe groups like the far-right John Birch worried many Americans. They thought that his temperament rendered him unfit for the presidency. Goldwater's defeat in 1964 was the most decisive in American history.

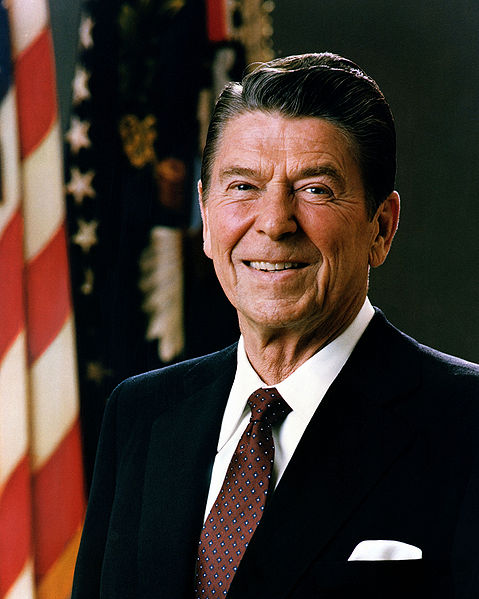

With these three as foils, Critchlow holds up Ronald Reagan as temperamentally best suited for the presidency. Reagan consistently showed ideological firmness, yet made political compromises when necessary. This pragmatism, combined with Reagan's natural affability made him a political success. Reagan displayed this "principled pragmatism" in 1980 when he chose moderate Republican George H.W. Bush to supplement his own conservatism. Critchlow argues that this choice demonstrated that "he was a pragmatist and not an ideologue" (128).

The complex relationship between the conservative ideologues Goldwater and Reagan is explored in Chapter Six, "Uneasy Allies, Goldwater and Reagan Compared." Both men catalyzed the rise of conservatism within the party, and shared similar political values. Yet, through their interactions and characteristics they "proved to be uneasy political allies... and presented to the electorate distinct personalities and temperaments" (131). Ultimately, Reagan's focus and discipline provided a broader appeal than Goldwater's short-temperedness and eccentricity.

Republican Character's Epilogue briefly summarizes America's long history of polarization. Critchlow insists that "judicious temperament and prudent character as fundamental to good leadership remains essential to the preservation of what our forebears envisioned" (158), a poignant observation given the nature of American politics in 2018. Critchlow ultimately argues that, despite flaws, the four men in this work proved principled yet malleable enough to make politics work.

Republican Character is not without its problems. Nixon, empty of character, won the presidency twice: the second time overwhelmingly. While Critchlow maintains that when it came to character, "GOP voters had misjudged [Nixon] with serious consequences for the health of their party and nation" (77), the reader wonders just how much character really matters to win elections.

The book also misses an opportunity, and an important mark of character, by not mentioning these men's political advisors. Rockefeller "too often...gathered around him sycophants too feeble in their dependency to tell him the need to accept defeat" (62). A number of Reagan's advisors wound up embroiled in the Iran-Contra scandal. To what extent is character personal and to what extent is it shaped, in the case of speeches and policy proposals, by others?

In our current political moment, the very idea of character in politics seems quaint. So, despite its shortcomings, Republican Character is a useful reminder that it once mattered more to politicians and to those who voted for them. Given the lack of civility and of political flexibility in Washington today, readers interested in the nature of political character and its relation to American democracy would do well to pick up Republican Character.