“Nothing equals the voluptuous power of feminine underwear,” could be the cursive lettering fronting a lingerie advertisement billboard in Times Square or featured as a line exclaimed with a British accent as supermodels strut about on TV. This claim, however, is something the Baronne d’Orchamps wrote over one hundred years ago in her book titled Tous les Secrets de la femme. Even then, the Baronne understood undergarments to be something powerful that gave women certain control over “the masculine brain.”

|

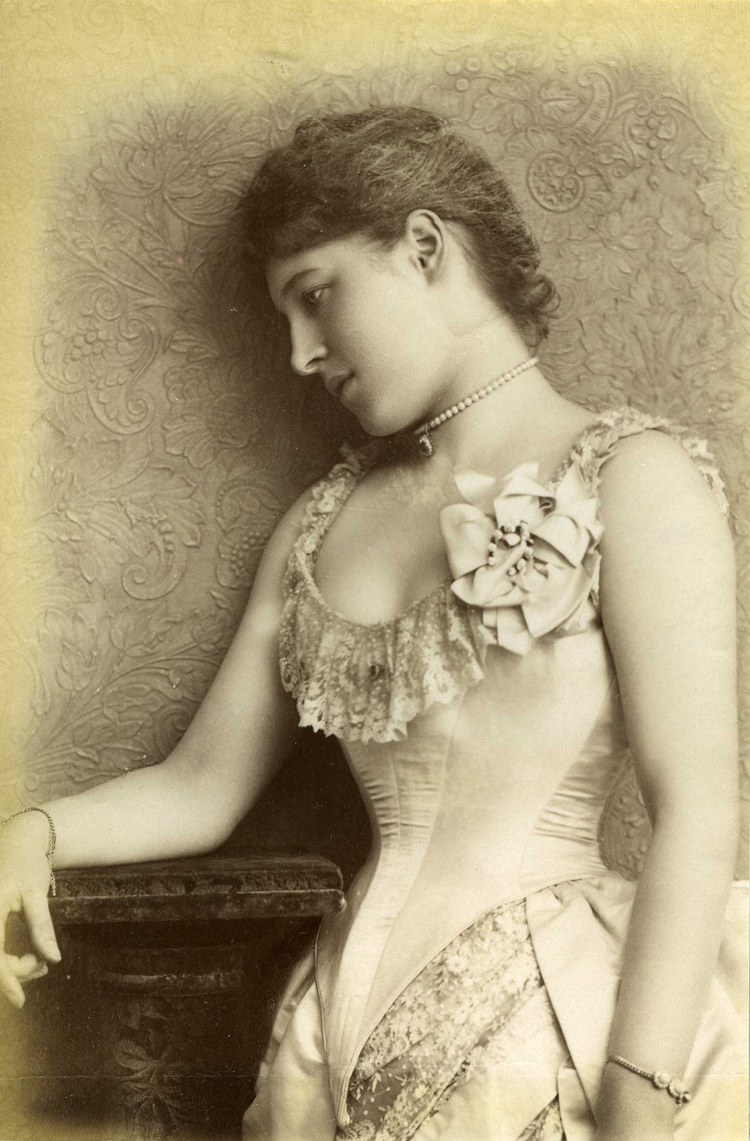

| Courtesans such as Lilly Langtry (in this 1885 photograph) are claimed to have started utilizing underwear as tool of seduction. |

Given the vast number of people, both men and women, who watch the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show every year, the Baronne’s observations remain relevant. There is just something intriguing about lingerie. But, this obsession with the layer of clothing closest to a woman’s skin did not materialize out of thin air as Colleen Hill explains in her fashion history Exposed: A History of Lingerie.

Tracing the evolution of what some designers refer to as humans’ “second skin,” Hill explores a realm of fashion that is, ironically, relatively uncovered. By tracing the history of lingerie - mostly through means of fashion photography and short accompanying descriptions - Hill attempts to describe lingerie design’s evolution and also hint at how its development has contributed to shifts in sexual mores and cultural perceptions of female sexuality.

Exposed reveals the variants of these undergarments, ranging from “soft shells” – the bras, panties, nightgowns, antiquated petticoats – to “hard shells” –the corsets, the bustles, the structured brassieres and girdles. When draped over mannequins, these artifacts come to life as one flips through the pages and watches the long flowing petticoats of the late eighteenth century give way to the tight black nylon bodysuit of the 2000s. These designs are documented through 70 full-color photographs with short descriptions, culled from a 2014 exhibit at New York’s Museum of Fashion Institute of Technology.

The written history here is confined to a short preface penned by Valerie Steele, a fashion historian, who describes the development of trends and styles in a concise eighteen pages. Tracing underwear designs across several centuries, she reveals a cyclical pattern where attitudes about propriety and fashion have appeared, faded and then reappeared. What surfaces as the major theme is how an interplay between fashion and function breeds a series of undergarment designs that also tap into the larger meaning of how women’s bodies are perceived in general society. The story of lingerie really could be one of liberation and gender control, if perhaps the author made room for this in her own analysis.

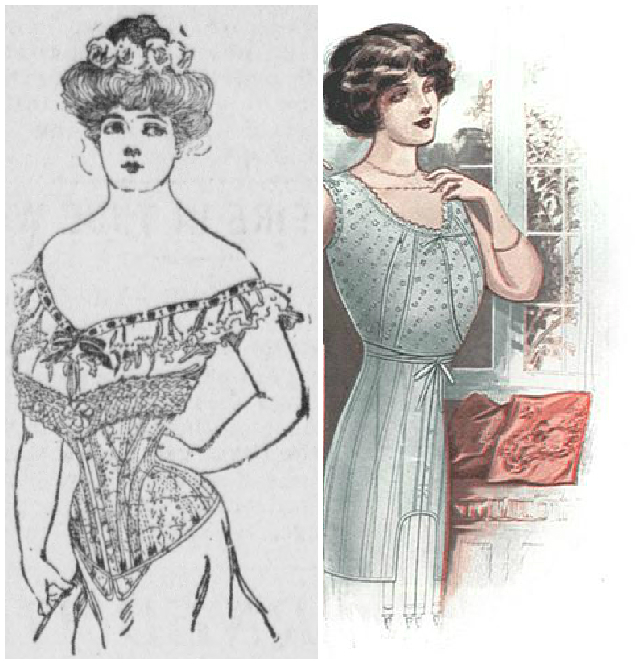

| This ladies underwear advertisement from 1913 highlights a fairly modest and simplistic lingerie design. |

As Steele explains it, in the beginning there was only the t-shaped undergarment (which later became the t-shirt) which both sexes donned to refrain from having to bathe too often or rendering their clothing too malodorous. Underwear existed as a practical and salubrious sheath of fabric. That is until royalty took to having these undergarments embroidered. Following this lead, courtesans allegedly began to employ more elaborate and tailored articles as seductive garments. Thus underwear became associated more with a female’s sexuality as it became more stylized and strictly functional questions were downplayed.

The brassiere in particular provides an example for how the relationship between function and fashion played out. Bras began as “bust supporters” in 1905 that were patented to create the then-coveted “monobosom” shape. By 1917, the bra became an essential undergarment for women – meant to cover the chest and also emphasize whatever silhouette was most chic at the moment. Thankfully, the “monobosom” look was replaced by a more natural look in the slimmer, deemphasized bust of the 1920s. The creation of the bandeau bra provided a delicate covering for the breasts without necessarily supporting or shaping them. This simple design also meant they could be mass-produced and made widely accessible.

|

| A snapshot of a typical Victoria’s Secret display exhibiting “sexy, but not pornographic” lingerie. |

In 1951, Marie Rose Lebigot of France ditched the simple bandeau design to create her famed lace corset, with its emphasis more on feminine lines sans body angles as underwired cups supported and emphasized the bosom. Fast forward ten years, and again a young feminine shape was preferred as a Vanity Fair bra called for the breasts to take a more “natural” shape. At the same time the Shelly Easy Rider Bra and panty designed in South Africa was described as “practically nothing to wear under everything” with a transparent-like quality that served solely as a covering rather than a structuring garment. Then the 1980s reintroduced classic lingerie styles, as the bustier again came back in vogue.

If the history of lingerie design feels a little schizophrenic, that’s because it is. The bustier in particular keeps fluctuating from serving as a confining creator of the “proper womanly form” to a more liberating and comfort-focused piece.

Missing from these pages of high-definition photographs is any context in which to consider these artifacts. We can see the shape of lingerie change over time but we aren’t offered any history to explain the variations. Likewise, while the photographs are compelling, most of the outfits shown here are draped on stiff mannequins. As a result, we don’t get any sense of the real women who actually wore them.

|

| Nightgowns are another form of lingerie which shifted from the alluring to the simple and comfortable. Here, three sisters lounge in their simplistically crafted nightgowns in the mid-1920s. |

Most obviously absent is an analysis of the relationship between what a woman puts on beneath her clothes in private and her place in the public realm throughout the 20th century. There is probably no definitive answer to the question of whether or not one form of undergarment becomes more or less empowering for women; as it also relates to the matter of taste and style that can change at any moment. This book is a lovely coffee-table accessory and a graphic history in its own right, but in the end, the sexy appearance of these outfits is obvious, but the sexy history is lost.