Although much remains the same, U.N. peacekeeping has undergone substantial changes in the face of new challenges since the early 1990s. The first peacekeeping missions of the United Nations monitored ceasefires and patrolled borders between combatant nations. Today, the peacekeepers confront complex intrastate violence, are more often peacemakers than keepers, and are frequently involved in long-term state- and civil-society-building projects.

Faced with humanitarian crises, outbreaks of civil war, and working in some of the world's most unstable places, United Nations peacekeeping missions are taxed to their limit. This month, historian Donald Hempson traces the evolution of United Nations peacekeeping over more than six decades to highlight the challenges associated with an ever more robust approach to international peacekeeping and conflict resolution. The limitations of the current model force supporters of UN peacekeeping operations to confront the hard questions of whether or not the United Nations is equipped for missions that now entail more peace implementation and enforcement than peacekeeping, especially in an environment of evermore diminishing resources and international will for prolonged and complex peacekeeping initiatives.

Read "Keeping the Peace" for more on the history of U.N. peacekeeping missions.

On July 1, 2011, the United Nations welcomed its newest member. South Sudan's January referendum on independence and subsequent peaceful separation from Sudan following years of violence marked a high point for U.N. peacekeeping, which had maintained the armistice there since 2005.

Yet, even as this tenuous victory unfolded, the Cȏte d'Ivoire's hellish descent into renewed violence reminded the world of U.N. peacekeeping's inconsistencies, shortcomings, and mounting challenges. Despite the presence of more than 9,000 U.N. peacekeepers, an estimated one million refugees were displaced by escalating violence in the wake of the country's contested November 2010 presidential elections. While U.N. and French forces eventually restored order in April, the peace remains fragile.

Also in Africa, the catastrophe unfolding in Somalia symbolizes some of peacekeeping's most abject failures. Twenty years, two U.N. peacekeeping missions, and one laborious African Union peacekeeping mission have done nothing to restore peace and stability to the Horn of Africa or to alleviate humanitarian crises there. Years of consternation over Somali pirates has shifted to impotent concern over a devastating famine exacerbated by decades of civil war.

What does the current state of affairs tell us about the nature of U.N. peacekeeping? Why, after more than six decades, is its legitimacy still debated regularly in the halls of the U.N. headquarters in New York City?

Undoubtedly, U.N. peacekeeping has restored peace and brought prosperity to millions of inhabitants in conflict zones around the globe.

Yet, expanding expectations for peacekeeping have strained the resources and mechanisms of the United Nations. Operational overstretch, shifting definitions of what peacekeeping should entail, and diminishing contributions (linked to a weakened global economy) are only the most recent obstacles to a function that has long tested the limits of the United Nations.

The Beginnings of United Nations Peacekeeping

In 1945, delegates from 50 nations met in San Francisco to draft a charter for a new international collective security organization determined "to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war." Since 1948, the United Nations (and its now 193 members) has conducted 67 peacekeeping operations from Central America to Southeast Asia.

For the vast majority of devastated populations around the world, the United Nations has become synonymous with peacekeeping. Yet, nowhere in the 111 articles that comprise the United Nations Charter can the word "peacekeeping" be found.

While not consciously chosen, "peacekeeping" operations arose from the UN's driving commitment to avoid the "scourge of war." The all-important justification for this peacekeeping function resides in Chapter VII of the charter, which stipulates that Security Council can authorize military action to safeguard international peace and security and respond to regional instability resulting from aggressive attacks on the sovereignty of member states.

Under Article 43 of this chapter, member states are obligated "to make available to the Security Council, on its call and in accordance with a special agreement or agreements, armed forces, assistance, and facilities … necessary for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security."

The United Nations, like many collective security alliances, was created in response to the last great threat to peace and security, in this case the two world wars. As such, the United Nations was built to respond to interstate conflicts (between two or more recognized states) and to safeguard the sovereignty of its member states. In order to avoid the inertness that plagued its predecessor, the League of Nations, the U.N. was endowed with rather robust enforcement protocols.

Despite its focus on safeguarding international peace and security, the United Nations was not constructed to confront the type of intrastate conflicts (between groups and peoples within a single recognized state) that almost exclusively dominate its peacekeeping agenda today.

Very soon after the United Nations' founding, Cold War tensions complicated decision-making under Article 43. Since any one of the Security Council's Permanent Five (P-5) can exercise veto rights in defense of broader geopolitical agendas, the ability of the U.N. to speak in a unified voice when authorizing military action has often proved difficult—especially as the Cold War animosity between the United States and the Soviet Union crystallized.

Despite these challenges, the United Nations confronted threats to peace and security with military action far more effectively than the League of Nations before it. In so doing, however, it was forced to develop "peacekeeping" within the parameters laid out in Chapter VII's passages on military operations.

First-Generation Peacekeeping

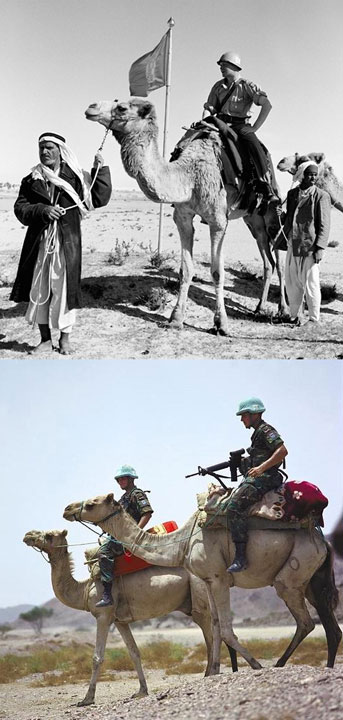

From 1948 until the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, the U.N. developed first-generation peacekeeping. There are some stark differences between that first iteration and what comprises second-generation U.N. peacekeeping today, but there are also shared characteristics.

Then as now, U.N. peacekeepers had to be invited by the host state and would not deploy until a ceasefire had been established. The invitation protected the sovereignty of member states, a paramount concern for the United Nations, and the ceasefire provided some sign that the belligerents were committed to resolving the conflict.

Yet, first-generation peacekeeping was more passive than it is today. Peacekeepers were deployed to keep the peace, not to restore peace or stop ongoing fighting.

U.N. peacekeeping forces consisted of lightly armed troops deployed to serve in a neutral capacity, physically interposed or inserted between opponents. Since U.N. peacekeepers were primarily a visible deterrent and a reminder of the international community's reciprocal commitment to resolving the conflict, peacekeepers did not need heavy weaponry and intentionally did not project an offensive military capability.

Armed only lightly and with their iconic light blue helmets, U.N. peacekeepers monitored ceasefires and remained in the field only so long as the invitation remained. Once an invitation was rescinded, the United Nations was obligated by its own rules of engagement to withdraw its forces and work to fulfill its mandate by other means.

This approach to peacekeeping was easy to reconcile with the language of the U.N. Charter, thus obviating any need to become fixated on the absence of the term "peacekeeping" in the Charter. Nevertheless, this model was not without serious limitations. Perhaps the best illustration of the challenges associated with first-generation peacekeeping is the initial U.N. Emergency Force (UNEF I) mission that was deployed to the Sinai region of Egypt from 1956 to 1967.

Trial in the Sinai

On October 29, 1956, Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt and quickly advanced westward toward the Suez Canal, which Egypt had nationalized in July to the consternation of Great Britain and France. Under the pretense of protecting the Suez shipping lane from Israeli-Egyptian fighting, British and French paratroopers landed in the canal zone within a few days of the Israeli invasion.

With three foreign forces deployed on its soil, Egypt petitioned the U.N. Security Council for assistance. When it met on October 31, it was stymied by the veto power of both Great Britain and France, so the issue was kicked to the General Assembly for resolution.

Following a ten-day emergency session, General Assembly Resolution 998 (1956) authorized the Security Council to deploy a peacekeeping force to Egypt and called for the immediate withdrawal of British, French, and Israeli forces from Egyptian territory.

U.N. peacekeepers were charged with overseeing these withdrawals and serving as a force physically stationed between Egyptian and Israeli troops in support of the ceasefire agreement. The limited rules of engagement set forth in the mission's mandate authorized the 6,000 peacekeepers to return fire only in self-defense.

For the next decade, UNEF I, deployed on the Egyptian side of the armistice line, patrolled the Sinai frontier and shouldered the burden of preventing a resumption of hostilities with a diminishing number of troops.

Then, in May 1967, the Egyptian government withdrew the invitation to U.N. peacekeepers. Less than three weeks later, the 1967 Six Day War broke out between Egypt and Israel leaving UNEF I with a problematic legacy.

The Sinai example highlights the limitations of the first-generation model of U.N. peacekeeping. Like many of the organization's military operations, the U.N. Security Council was susceptible to the intransigence of its five permanent members.

Even when stalemates could be avoided, the limited nature of first-generation peacekeeping meant there was often a split verdict on its utility. On one hand, UNEF I maintained the peace between two hostile neighboring states for 10 years. On the other hand, it did very little to resolve the underlying cause of the conflict as demonstrated by the outbreak of war once U.N. peacekeepers were out of the picture.

Second-Generation Peacekeeping

Second-generation peacekeeping was born on the fly and out of a necessity to address the far more complex nature of the ethnic and communal violence that increasingly confronted the United Nations at the end of the Cold War. It moved peacekeeping beyond the passive interposition role into something far more involved and multidimensional.

The early 1990s ushered in a short-lived optimism about U.N. peacekeeping. Tensions among the P-5seemed to dissipate and many looked forward to a new era of peacekeeping operations purged of the partisanship generated by Cold War adversaries.

The grim flip side was that many of the smaller conflicts that the Cold War superpowers had held at bay were now free to explode unchecked. In the absence of Soviet or American patronage, many developing states around the globe began to fracture and spiral into chaos fueled by resurgent nationalism, political instability, and contested natural resources.

The United Nations confronted an alarming proliferation of bloody and primal intrastate conflicts throughout much of the Global South. Its first-generation model of peacekeeping now appeared inadequate and ill-designed for these new types of clashes.

The United Nations was forced to expand its understanding of what peacekeeping entailed to include long-term conflict resolution. Peacekeeping quickly evolved from a limited role of symbolic deterrence primarily charged with monitoring an existing ceasefire to an active one that involved in-depth conflict resolution and peace enforcement. U.N. peacekeeping crept ever closer to peace implementation and enforcement.

Peacekeeping remained predicated on preventing the resumption of hostilities between warring parties, but beginning in the 1990s, its approach to resolving the underlying conflict also became more robust. United Nations peacekeeping missions were increasingly charged with laying the foundation for a self-sustaining peace: implementing political solutions to the conflict, shoring up transitional governments, providing economic assistance for post-conflict states, and shouldering the responsibility for humanitarian assistance during the transition period.

One of the lessons taken away from UNEF I was the need for peacekeepers to be more involved in resolving the underlying conflict. Adhering strictly to an interposition role was insufficient because it did little to create conditions for a lasting peace in the absence of international actors.

If these lessons were important when the combatants were state actors with clearly defined borders and agendas, they became vital with the types of conflicts increasingly confronting the United Nations beginning in the 1990s, which involved both state and non-state actors with sometimes tenuous or nonexistent political structures as well as shifting or incoherent agendas. The security provided by U.N. peacekeepers was illusory without an accompanying political solution.

The United Nations began to acknowledge a responsibility to not only protect the state, but also the citizens of the state victimized by the conflict. U.N. peacekeepers came to realize that providing adequate relief for refugees and displaced persons is an indispensable component of the peace process. Without a sense of personal security, citizens cannot help create and sustain the conditions for permanent conflict resolution.

Maintaining a static security perimeter was not enough. The United Nations began to emphasize humanitarian functions such as election monitoring, civil society building, police and judicial reforms, civil reconstruction, protection of heritage sites, and financial reform. Peacekeeping missions became more multidimensional and the skills of peacekeepers became ever more specialized.

For instance, caring for victims has evolved beyond simply providing access to basic necessities—food, shelter, medical assistance—to providing counseling and psychological aid to those traumatized by rape, child soldiering, and other atrocities.

Unlike during first-generation peacekeeping, disarming and demobilizing combatants now necessitates more than establishing weapons collection points and observing demobilization.

Peacekeepers must determine a "normal" level of weaponry acceptable within a given population based on sociocultural factors (and the need for personal security in lawless situations), and demobilized combatants must be re-integrated into society. This often involves skills re-training, basic education and literacy programs, and public outreach initiatives to allay any fears the public may have about the presence of former combatants.

Election monitoring involves more than securing polling stations and safeguarding the ballot boxes. It has become a process of engagement with—or creation of—civil society organizations to determine the size of the electorate and incentivize public participation. It might also involve literacy programs to enable voter participation.

More often than not, the expanded role of peacekeepers also includes tight coordination with humanitarian and refugee agencies and communicating the benefits of cooperating with U.N. operations.

The United Nations quickly realized it required an infrastructure geared toward these more expansive missions. In 1992, it formed the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) as a centralized command for all missions. It is responsible for all U.N. peacekeeping operations and serves as the conduit between missions in the field and the Security Council, which continues to authorize all activities.

In the 19 years since its creation, the DPKO has been expanded and enhanced to include a greater degree of interoperability with other U.N. agencies and outside partners. As the DPKO quickly discovered, its new approach to peacekeeping required the coordination of a broad spectrum of operators, each bringing their own particular competency to the peacekeeping brand of conflict resolution.

Initially created to oversee one or two peacekeeping operations per year, the DPKO currently manages 15 peacekeeping operations, with the possibility of additional mission mandates always on the horizon.

The Balkan Test

One of the first full-blown peacekeeping missions of the 1990s demonstrated how the playing field for peacekeeping had changed and foreshadowed the challenges ahead. When Yugoslavia disintegrated into an orgy of ethnic and communal conflict, the United Nations seemed unprepared for the new realities of post-Cold War peacekeeping. The peacekeeping mission to the breakaway regions of Yugoslavia quickly began to redefine the structures and goals of second-generation peacekeeping.

As the Yugoslav federation was torn apart, the rhetoric of all parties to the expanding conflict became increasingly laced with both nationalist and ethnically charged language. By the time Bosnia declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1992, many outside observers were unwilling to distinguish between the political objectives of the various nationalist leaders and the charges of ethnic division. [Read Origins for more on the conflict in the former Yugoslavia and Kosovo.]

In an attempt to referee the violence, the Security Council formed the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), which aimed to safeguard civilian populations caught up in the increasingly bloody dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Beginning in 1993, this mandate was expanded to include the monitoring of six safe havens established in southeastern Bosnia for Muslims seeking sanctuary from the ethnic cleansing campaign being perpetrated by Bosnian Serb forces. The United Nations' early attempts to keep the peace in Bosnia illustrate the steep learning curve the organization experienced.

UNPROFOR initially relied on the traditional model of deploying lightly armed interposition forces into a conflict zone. The problem with following this model in Bosnia was that the ceasefire was as fluid as the front lines and theaters of operation. The rules of engagement were poorly conceived and the international community's commitment to resolution of the conflict appeared weak.

This was never more apparent than in July 1995 when approximately 600 Dutch peacekeepers surrendered the Srebrenica safe haven to a vastly larger Bosnian Serb force following a prolonged assault.

Cut off, denied close air support because of improperly filed forms, and concerned for the welfare of 30 Dutch peacekeepers held hostage by Bosnian Serbs, the Dutch commander in Srebrenica negotiated surrender. The subsequent massacre of 8,000 Bosnian Muslim boys and men by Bosnian Serbs discredited UNPROFOR and disgraced the international community.

In the aftermath of this fiasco, NATO bombing of Bosnian Serb locations and a United States-led negotiation mission resulted in the November 1995 Dayton Peace Accords, creating the United Nations Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (UNMIBH). UNMIBH embodied a new model of peacekeeping as a response to communal and ethnic conflicts.

The Yugoslav experience taught the United Nations that peacekeeping requires a demonstrated commitment and a composite force capable of legitimizing institutions critical to the security of the population and the long-term viability of the state. This entails a broad range of functions that now include election monitoring, political and judicial reforms, resettlement of refugees, investigation and prosecution of war crimes, civil reconstruction projects, education, literacy programs, skills retraining, and economic rehabilitation.

Simply put, second-generation peacekeeping demands a broader range of actors with more developed competencies and a longer-term, more forcefully articulated commitment to conflict resolution.

Another lesson from the Balkan experience was the need to coordinate a variety of agencies, organizations and actors. No fewer than three entities—the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), and the Council of Europe—had intersecting responsibilities for human rights provisions as they pertained to election monitoring, regional security issues, constitutional reforms, and political, social, and economic improvements throughout Bosnia.

Similarly, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the Red Cross, the International Police Task Force (IPTF), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) shared overlapping responsibilities as they pertained to investigating war crimes, protecting internally displaced persons, addressing human rights issues, and building confidence among the local population.

Thus, peacekeeping in Bosnia introduced the DPKO to the bureaucratic challenge of coordinating multiple agencies tasked with various elements of a second-generation peacekeeping mission. It also introduced the DPKO to the paramount importance of instilling confidence in the local population and demonstrating an unwavering and international commitment to conflict resolution.

On the Horn of Africa

Even before Bosnia imploded into ethnic cleansing, on another continent, Somalia had descended into a civil war. Attempts to keep the peace there also highlight the challenges of and the need for a more robust approach to second-generation peacekeeping.

Responding to both the civil war and a mounting humanitarian crisis, in 1992 the United Nations created the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM). UNOSOM was charged with enforcing a U.N. arms embargo, monitoring a U.N.-brokered ceasefire, and delivering aid to nearly 1 million refugees and 5 million sick and starving people.

Warring Somali forces ignored the ceasefire and increasingly attacked humanitarian aid convoys. These wanton attacks and the unwillingness to abide by the ceasefire strained the will of the international community and convinced the United Nations that its humanitarian mission required much more muscle than a lightly armed interposition force.

In 1992, the United States was authorized by the United Nations to deploy the Unified Task Force (UNITAF) to Somalia and to use "all necessary means" to provide a safe operating environment for international relief workers. UNITAF was given an enforcement mandate that was not typical of peacekeeping missions at that time.

Despite deploying more than 37,000 highly trained and well-equipped troops, UNITAF faced an operating environment openly hostile to international intervention of any kind and a famine that was accelerating the humanitarian crisis in Somalia.

By 1993, UNOSOM and UNITAF were rolled into UNOSOM II, a U.N. peacekeeping mission with much the same mission as its predecessors, but more directly under U.N. control and with a larger operating environment. With approximately 22,000 troops, the U.N. peacekeeping mission was doing more with less and beginning to suffer the consequences of diminishing political will among its member states.

By 1994, following mounting and high profile casualties—most famously for Americans the events of the Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993, depicted in the book and film Black Hawk Down—the United States and several European powers began withdrawing their troops, signaling the collapse of international commitment to peacekeeping in Somalia.

UNOSOM II was decommissioned in March 1995, citing "troop withdrawals, budget restrictions, and military actions by Somali factions" as the reason for the mission's failure. In three years, the various U.N. peacekeeping missions in Somalia had been unable to restore peace or provide the necessary humanitarian aid to a devastated population. Second-generation peacekeeping was beginning on very poor footing.

Sixteen years later, the international community is once again confronting a humanitarian crisis exacerbated by civil war in Somalia. Tens of thousands of refugees continue to flee across the border to neighboring Kenya as famine and disease claim untold lives. Now, as then, armed factions within Somalia are openly hostile toward international humanitarian relief and peacekeeping operations.

The Future of United Nations Peacekeeping

In the nearly two decades since the United Nations ventured into second-generation peacekeeping in both Bosnia and Somalia, the organization has come to recognize the limitations of its approach to peacekeeping. Still haunted by the memories of UNOSOM and conscious of a mixed record of peacekeeping elsewhere in Africa (perhaps most notably in Rwanda), the United Nations has repeatedly refused to deploy a third peacekeeping mission to Somalia.

Yet as this crisis continues to unfold, the United Nations must reflect upon its own commitment to the principle of peacekeeping and determine whether an appropriate strategy exists that can responsibly and effectively balance its ideal of saving the world from the "scourge of war" with the realities on the ground in these conflict zones.

Beginning in the 1990s, peacekeeping became more complex and in reality became less about keeping an existing peace and more about implementing and enforcing an externally imposed peace.

The United Nations expanded the function of peacekeeping to meet the challenges of a post-Cold War landscape. As peacekeeping increasingly responded to internal conflicts and civil wars, the political, economic, social, and security functions became more complex and required greater participation by a broad array of international and regional organizations.

All of this occurred in an increasingly interconnected world. As the number of U.N. peacekeeping missions exploded over the past two decades, so did the attention they received. What happens in one theater of operation is no longer isolated and peacekeepers' actions in one mission can impact their effectiveness in another.

The recent political and refugee crisis in the Cȏte d'Ivoire not only strained the capacity of it mission there (UNOCI), but also threatened to jeopardize the activities of the neighboring United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL). Peacekeeping successes and failures no longer exist in a vacuum.

The seemingly endless cycle of peacekeeping missions has led to operational overstretch and a weariness among member states for a process that resembles a game of "Whack-A-Mole." The world is an obstinately violent place and particularly in light of the global financial crisis, member states are inclined to downgrade their commitment to peacekeeping operations.

As U.N. peacekeeping has become ever more robust, it has often committed to doing more with less—a condition that does not seem likely to change in the foreseeable future. What then is the role of U.N. peacekeeping for the coming decade?

The answer may lie somewhere between first- and second-generation peacekeeping: an approach that continues to stress an international commitment to conflict resolution, but is less invasive, expensive, and drawn-out. For this to work, the United Nations must continue to nurture the capabilities within its network of agencies. It must also ensure the willingness of member states and regional organizations to commit to a coherent peacekeeping agenda.

The limited success in South Sudan offers some hope, but the Cȏte d'Ivoire and Somalia continue to offer cautionary tales. The United Nations is most certainly justified in not rushing into another poorly conceived and uninvited peacekeeping mission in Somalia. There is no commitment to peace by the various parties to the conflict and therefore no basis for peacekeeping.

Nevertheless, there is an image the U.N. member states must safeguard. If the international community waits too long to intervene, as it was perceived to do in Bosnia, it runs the risk of delegitimizing the peacekeeping function and alienating the very people it needs to build conditions for a self-enforcing and sustainable peace.

As the newly appointed Under-Secretary-General of Peacekeeping Operations, Hervé Ladsous, took the helm on September 2nd of this year, the questions surrounding the way forward for U.N. peacekeeping are no less difficult than the task of peacekeeping itself and may require a step back—a conscious reassessment of goals and capabilities in the 21st century—before taking the next leap forward.

Peacekeeping in General

UN Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines:

http://www.peacekeepingbestpractices.unlb.org/pbps/library/capstone_doctrine_eng.pdf

A New Partnership Agenda: Charting a New Horizon for UN Peacekeeping:

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/documents/newhorizon.pdf

Bellamy, Alex J., Paul Williams, and Stuart Griffin. Understanding Peacekeeping. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004.

Call, Charles T. and Vanessa Wyeth, eds. Building States to Build Peace. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008.

Cousens, Elizabeth M,., Chetan Kumar, and Karin Wermester. Peacebuilding as Politics: Cultivating Peace in Fragile Societies. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001.

Diehl, Paul F. and Daniel Druckman. Evaluating Peace Operations. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2010.

Doyle, Michael W. and Nicholas Sambanis. Making War and Building Peace: United Nations Peace Operations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Fenton, Neil. Understanding the UN Security Council: Coercion Or Consent? Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004.

Fortna, Virginia Page. Does Peacekeeping Work?: Shaping Belligerents' Choices After Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Howard, Lise Morjé. UN Peacekeeping in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Hurwitz, Agnes and Reyko Huang, eds. Civil War and the Rule of Law: Security, Development, Human Rights. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008.

Olara A. Otunnu and Michael W. Doyle, eds. Peacemaking and Peacekeeping for the New Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998.

Ratner, Steven R. The New UN Peacekeeping: Building Peace in Lands of Conflict After the Cold War. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995.

Sitkowski, Andrzej. UN Peacekeeping: Myth and Reality. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006.

Stephen John Stedman, Donald Rothchild, and Elizabeth M. Cousens, eds. Ending Civil Wars: The Implementation of Peace Agreements. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2002.

Bosnia and the Balkans

Andreas, Peter. Blue Helmets and Black Markets: The Business of Survival in the Siege of Sarajevo. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Belloni, Roberto. "Civil Society and Peacebuilding in Bosnia and Herzegovina," Journal of Peace Research 38 (2001), 163-180.

Burg, Steven L. and Paul S. Shoup. The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. North Castle, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000.

Caplan, Richard. "International Authority and State Building: The Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina," Global Governance 10 (2004), 53-65.

Corwin, Phillip. Dubious Mandate: A Memoir of the UN in Bosnia, Summer 1995. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Farrand, Robert W. Reconstruction and Peace Building in the Balkans: The Br?ko Experience. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2011.

Gow, James. Triumph of the Lack of Will: International Diplomacy and the Yugoslav War. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Leurdijk, Dick A. "Before and After Dayton: The UN and NATO in the Former Yugoslavia," Third World Quarterly 18 (1997), 457-470.

Okuizumi, Kaoru. "Peacebuilding Mission: Lessons from the UN Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina," Human Rights Quarterly 24 (2004), 721-735.

Somalia and Africa

Clake, Walter Sheldon and Jeffrey Ira Herbst. Learning from Somalia: The Lessons of Armed Humanitarian Intervention. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997.

Francis, David J. Dangers of Co-deployment: UN Co-operative Peacekeeping in Africa. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005.

Lyons, Terrence and Ahmed Ismail Samatar. Somalia: State Collapse, Multilateral Intervention, and Strategies for Political Reconstruction. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1995.

Mohamoud, Abdullah A. State Collapse and Post-Conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2006.

Sahnoun, Mohamed. Somalia: The Missed Opportunities. Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press, 1994.

Useful Links

United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/about/dpko/

United Nations Peacekeeping Organization Chart:

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/documents/dpkodfs_org_chart.pdf

The "New Horizon" Process:

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/operations/newhorizon.shtml

United Nations Operation in Somalia I (UNOSOM I):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/unosomi.htm

United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/unosom2.htm

United Nations Mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina (UNMIBH):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/unmibh/

United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/unprofor.htm

United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unmiss/

United Nations Operation in C?te d'Ivoire (UNOCI):

http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unoci/

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR):

http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home