In 1991, explaining why it would have been a mistake to invade Baghdad after the Gulf War, Dick Cheney warned that removing Saddam Hussein would have inflamed ancient tensions between Sunnis and Shi’i. His fears were realized 15 years later when Iraq descended into a civil war from which it has not recovered. Journalists, commentators, and policy makers usually refer to this religious conflict as intractable with origins that date back over 1000 years. But as historian Stacy E. Holden writes this month, the real source of the region's conflicts are more recent and more secular. They can be traced to the political patterns and preferences of the Ottoman empire. And, over the 100 years since the end of Ottoman control in Iraq, those same power dynamics have continued to dominate the region through British imperialists, Baath-party power, and the U.S. occupation.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on the Middle East: ISIS; U.S.-Iraq Relations; The U.S. War in Iraq; Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; the Alawites and Syria; U.S.-Iranian Relations; Turkey’s Politics; and The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

The Islamic State (ISIS) in Iraq, centered in the central and northern part of the country, is a place where leaders torture and kill people who do not follow a draconian interpretation of Sunni Islam.

But ISIS has a particular hostility toward followers of Shi’i Islam, as three incidents from the summer of 2014 highlight. ISIS ordered the mass murder of 1,500 Shi'i militiamen in Tikrit, a Sunni stronghold and the former hometown of Saddam Hussein. When ISIS forces drove through villages surrounding Kirkuk, Shiite families played dead in the hopes that they would not be gunned down with others of their same identity. And when the Islamic State captured a prison in Mosul, its leaders ordered all Shi'is and other minority peoples into a ditch and killed them.

Such targeted killing of non-Sunnis, particularly of those born as Shi'is, led a reporter for The Economist in September 2014 to write that the Islamic State “is both the product and the chief instigator of the ever deepening Sunni-Shia enmity that runs from Bahrain to Lebanon.”

In Iraq, the population is approximately 60% Shi'is and 20% Arab Sunnis. There is a widespread sense that the present conflict between these two sectarian groups is a case of longstanding, theologically driven hatreds reasserting themselves again. As such, some political pundits conclude, negotiations cannot overcome divine principles dictating distinct worldviews that preclude peaceful coexistence and the forging of a coherent nation-state.

When the Western media does inject pragmatic power considerations into its analysis of sectarian tensions in Iraq, they are of courte durée. Journalists often blame the present crisis on former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. He came to office in 2006 and used his position to promote Shi'i interests at the expense of the Sunni minority.

|

| Religious and Ethnic groups in Iraq. |

Many posited that Prime Minister al-Maliki's resignation in September 2014 and the appointment of the more inclusive Haider al-Abadi would improve the situation in Iraq. After all, Mr. al-Abadi formed a government consisting of both Shi'is and Sunnis, thereby making a deliberate effort to draw support from the Sunni Islamic State. And yet, more than one year after his appointment, the Islamic State has yet to be neutralized.

Sunni and Shi'i identities have both religious and political dimensions. And it is the politics, I argue, that causes the conflict in Iraq, while the religion provides a rhetoric accentuating difference between political players. In this way, there are secular roots to the animosity that many outsiders view as an ancient and irreconcilable religious divide.

In order to understand the interplay between politics and religion we need to look back at the closing stages of the Ottoman era and the rise of modern nations in the Middle East. The recent Sunni-Shi’i struggles for power and for influence over the institutions of the state emerged within the dynamics of the Ottoman era, when this Sunni empire contended for land and treasure with Shi'i Persia.

| Imam Ali Mosque, Najaf, Iraq. |

The Ottoman Empire ended 100 years ago, but its legacy still influences sectarian relations in Iraq. When European powers disbanded it after World War I, most power brokers in its Iraqi provinces were Sunni Arabs who had proven loyal to the Ottomans in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This would have long-term implications for the development of modern Iraq, because these Sunnis and their descendants were able to perpetuate their monopolization of the institutions of the Iraqi state.

The present aggravation of relations between Sunnis and Shi'is in Iraq is less a legacy of religious conflict than a manifestation of Ottoman policies enunciated amidst that empire's troubled end.

The Sunni-Shi'i Split

The Sunni-Shi'i split dates to 10 October 680 CE (10 Muharram 61), and its origins stem from a war over control of the power—both political and economic—of the nascent Islamic empire being forged at that time. Power and influence, not dogma and doctrine, were at the core of the Sunni-Shi'i divide from its very beginning.

Islam spread quickly in the area now called the Middle East. By the time of the Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632, Muslims had united the Arabian Peninsula. The Prophet’s successor, Abu Bakr (r. 632-634), led the first military excursion into the area that is now Syria and Iraq. (This historic detail explains why Islamic State “caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi took this nom de guerre.) Abu Bakr as well as the next three so-called Rightly Guided Caliphs were chosen by a consensus of the community. This was not a democracy; it was instead a participatory oligarchy.

The concord sustaining this oligarchy during the first 48 years of the Islamic Empire crumbled in 680, as the Muslim elite and their followers struggled to control the financial and political structures of the emerging Islamic empire.

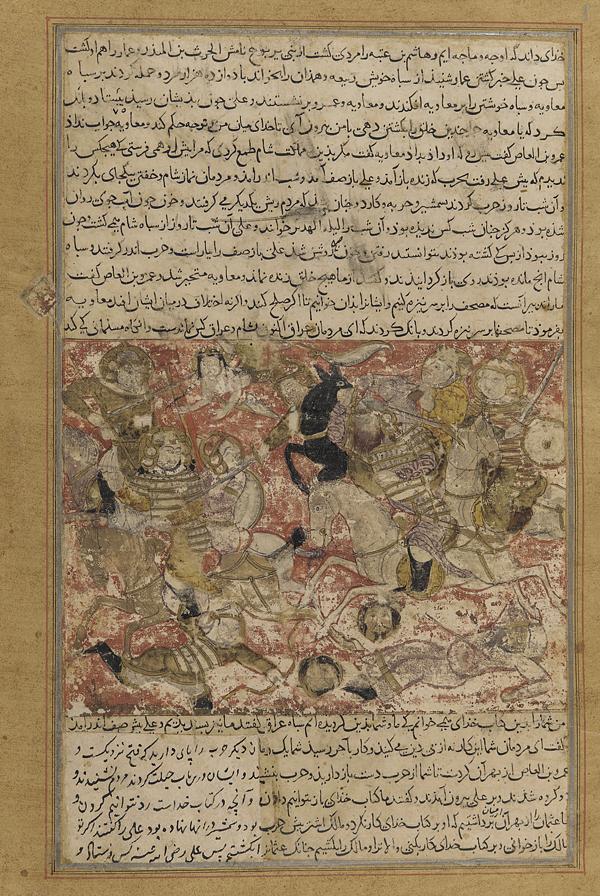

|

| Hasan ibn Ali served his father, Ali, during the Battle of Siffin, 657 CE. Folio from a 14th century Tarikhnama (Book of history) by Balami. |

The defining crisis stemmed from the assassination of Ali (r. 656-661), son-in-law of the Prophet and the last of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, as he prayed at a mosque in Kufa, a city in present-day Iraq.

After Ali's death, two factions supported two different rulers. Some championed the appointment of Hassan, a son of Ali and so a grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Others backed Muawiyya, based in what is now Syria, who controlled the most powerful army in the Islamic Empire.

Ultimately, Hassan and his brother Husayn, fearing civil war, came to an agreement with Muawiyya. In 661, they ceded state power to him as long as he agreed not to establish a dynasty. This was not to be, for his son Yazid claimed state authority upon his father’s death 19 years later. Yazid proclaimed himself a king of the new Islamic empire by virtue of family ties. And so, community participation gave way to a system of dynastic succession by which power was transferred based on bloodlines, not merit or a consensus of the community.

This conflict of dynastic succession culminated in Karbala, in modern Iraq, when Yazid’s troops mercilessly slaughtered Husayn and 70 of his followers in an event now commemorated as ashura. Shi'is believe that Husayn was a martyr who died the rightful leader of the political community.

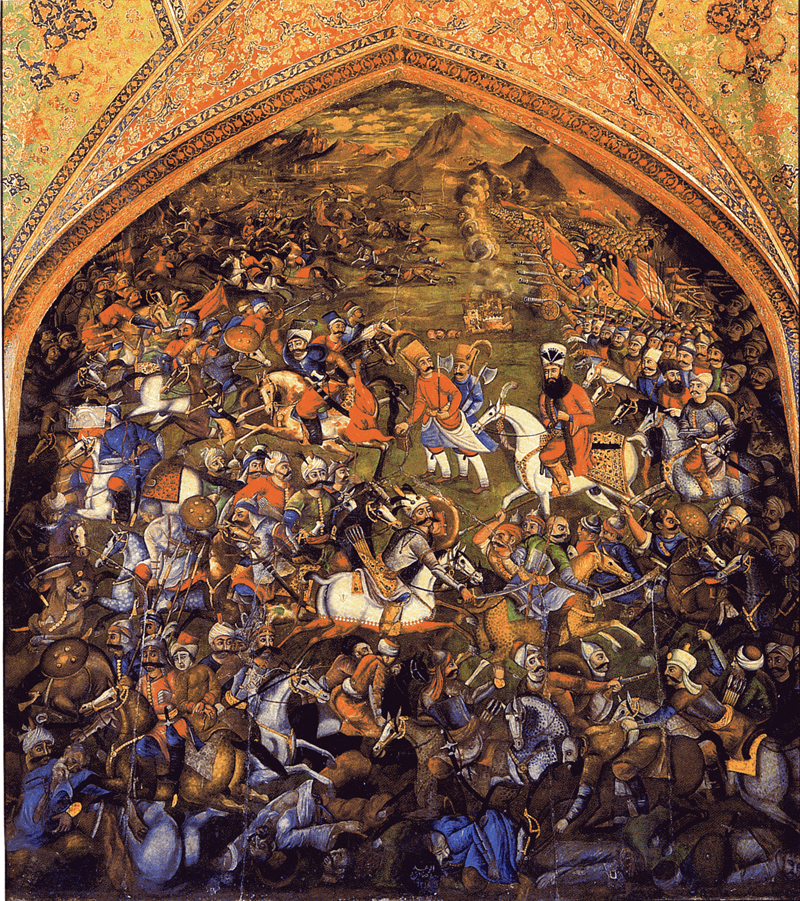

|

| Pilgrims gather for the ashura commemoration in Karbala, Iraq, January 19, 2008. The 10-day event commemorates the death of Husayn. |

This confrontation and resultant massacre engendered the Sunni-Shi'i split. Sunnis were content to have Yazid emerge victorious and establish the first great Islamic dynasty, one that would rule territories in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Shi'is continue to decry this Battle of Karbala as an internecine tragedy, insisting the power of the state should have passed to Husayn.

In general, there is nothing culturally divisive about the Sunni-Shi'i split. Adherents of both sects celebrate the same holidays. They read the same Quran. They both pray five times a day facing Mecca.

Given such, it is not surprising to find that many provinces within the Arab-Islamic world have experienced normalized relations at certain times in history and also moments when Sunnis and Shi'is found that they could act in concert.

For example, in 750 CE, Sunnis and Shi'is together participated in the Abbasid Revolution, which would put in place a dynasty, the Abbasids (750-1258), remembered as fostering an inclusive and multiethnic state.

And in Iraq, Sunnis and Shi'is have often managed to maintain their own distinct religious customs while co-existing peacefully.

|

| The Battle of Karbala, 680 CE. Painted by Abbas Al-Musavi between 1868 and 1933. |

Nonetheless, the historic bid for power on the Fields of Karbala did lead to one important dogmatic difference between Sunnis and Shi'is: the Shi'i Doctrine of the Imamate. The prophet Muhammad had been a religious, political and military leader. Yazid and his successors, who represented the Sunni conception of leadership, assumed only the political and military duties, leaving scholars to debate religious questions and settle them by consensus.

For Shi'is, however, there is one Imam who, though not a prophet, is a divinely inspired religio-political leader of the community. He is the authoritative interpreter of God's will as formulated in Islamic law, a law that, given his divine inspiration, he best understands. In this way, Shi'is believe in continued heavenly guidance through the divinely inspired leadership of an Imam.

More importantly, based on subsequent interpretations and understandings of the Sunni-Shi'i split, the overlords of Iraq—the Ottomans, the British, and the Baath party—all implemented policies based on mistaken assumptions about the divided loyalties of Shi'is. Shi'is, in turn, used the rhetoric of what these rulers perceived as a rival faction of Islam to oppose an authoritarian political system dominated by adherents of Sunni Islam.

The Ottoman Wars with Persia

The factionalism that now beleaguers Iraq stems from this seventh-century conflict as enunciated and acted upon during the Ottoman Empire, particularly during its waning days in the in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Forged from the military forays of Turkish nomads in the early 14th century, the Ottomans, Sunni nomads from Anatolia, succeeded the Abbasids as the next great Islamic dynasty. Ottomans were a warring people, for the conquest of territory legitimized the rule of the reigning caliph. But the dominance of Eastern Persia prevented their conquest of territory beyond the Iraqi provinces, which became oft-contested borderlands.

By the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire had ruled the area now known as Iraq—then referred to by Westerners as Mesopotamia—for 300 years. This Mesopotamian territory consisted of three Ottoman provinces, with each centering on a principal city.

|

| Map of Mesopotamia. |

Basra was in the coastal south, and this was where the population was—and still is—predominantly Shi'i. Baghdad was in the central plains, and the people there were—and still are—primarily Arab and Sunni. Mosul was in the mountainous north, the heart of primarily Sunni Kurdish territory.

The 2.2 million inhabitants of this territory were at the easternmost limit of the Ottoman Empire, next to Persia, which, unlike the Ottoman Empire, was a polity ruled and inhabited almost exclusively by Shi'is (90% or more of the population practiced Shi'ism). The Shi'is in these Iraqi provinces increasingly became a marginalized majority and the Ottomans feared that the provincial Shi'is did not share their Sunni subjects’ loyalty to the imperial state.

As Sunnis, Ottomans feared that their Shi'i subjects in Mesopotamia might fall under the sway of prominent Shi'i religious scholars and clerics in Persia and so act against Ottoman interests.

Neighboring Persia also regularly threatened—often in retaliation for Ottoman forays into its territory—an invasion in order to take the provinces of Basra and Baghdad. A Sunni dynasty was pitted against a Shi'i one. Ottoman and Persian forces fought wars in 1548-1555, 1574-1589, 1603, and 1616. In 1623, Persia managed to capture Baghdad, which it occupied until 1638.

|

| Ottoman and Persian Empires, circa 1912. |

Following a peace treaty, relations between the two political entities remained at a standstill until the late 18th century, when Persia, now under the Qajar dynasty, again threatened an offensive. By 1823, the Ottomans and the Qajars had already fought nine wars, leaving little doubt that inter-imperial bellicosity would not diminish even as, later in the century, a new generation of Young Ottomans and Persians began to pressure the government for constitutional reform.

And so, the leaders of the Ottoman state decided to enact policies to protect against Shi'i subversion. For example, they promoted only Sunnis, not Shi'is, in the military and the government. In this way, Sunnis in the provinces of Iraq came to have more access to the economic and political benefits of the formal institutions of the evolving state.

Sunni Dominance and British State Formation

After World War I, England and France amalgamated the provinces of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra to create the new state of Iraq. The British ruled this country for twelve years as a mandate. The British reified sectarian divisions fostered by 19th-century Ottoman policies, keeping the Sunnis as the political elite and perpetuated the Sunni dominance inherited from Ottoman era.

The British conceptualized Shi'is as restive and prone to irrational forms of protest. In the Ottoman era, Shi'is generally commemorated the death of Husayn, or ashura, with more fervor than Sunnis.

|

| British troops entering Baghdad, Iraq March 1917. |

For example, many Shi'i villages and towns held a type of Islamic passion play that gave life to the massacre of Husayn and his 70 followers by an oppressive ruler, and this became an allegorical treatment of how economically and politically deprived Shi'is felt under the Ottomans. Some Shi'is who paraded to mosques in cities—as in Kufa, where Ali had been assassinated—practiced self-flagellation. This led one horrified Englishman to declare Shi'is “terrifying in their single-mindedness … savage and revengeful.”

Shi'is were eager to contribute to the nascent state, but they were not enthusiastic about a system of colonial governance.

Thus, there was a revolt in 1920, one in which Sunnis and Shi'is often acted in concert against the British. Anti-colonial discourse in Sunni and Shi'i mosques could be heard as early as May, and armed revolt in the countryside began in June. Within five months, 500 British troops had been killed in action while as many as 10,000 Iraqis lay dead.

Most importantly for the sectarian divisions in Iraq, the British blamed primarily Shi'i clerics who had spoken vociferously against a system of governance that they rightly grasped as blatantly unjust. The British jailed and exiled many Shi'i clerics, like Mahdi al-Khalisi.

|

| King Faysal I. |

In 1921, British politicians appointed Amir Faysal to rule over Iraq as a king, thereby establishing a new Sunni dynasty. Born in 1885 in Mecca, a city in the Arabian Peninsula that Muslims consider the holiest in Islam, Faysal had proven himself amenable to British interests. In 1916, he had participated in the celebrated Arab Revolt, a conflict that neutralized 30,000 Ottoman troops on the eastern front.

The British hoped that Faysal's putative descent from the Prophet Muhammad would legitimize this new dynasty. The new king brought with him a Sunni cohort to assist in ruling over Iraq. In this way, British rule promoted Sunni interests over those of Shi'is.

When the British allowed Iraqis to rule Iraq as independent country in 1932, Faysal promised “full and complete protection of life and liberty will be assured to all inhabitants of Iraq without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race or religion.”

Such a democratic notion, however, proved difficult to implement because the Sunni elite did not want to give up their political and economic advantages. Faysal and his successors—the Hashemite dynasty—did not fashion a pluralistic regime.

After all, a true constitutional monarchy in which democracy flourished in the majority-Shi'i state would have been inconvenient for the Sunni elite, who were rather enamored with their privileged position, and for their British patrons, who, concerned with investments in the oil industry, did not want to risk a government unfavorable to their interests.

Thus, a cycle of political violence came to define Iraqi politics throughout the 20th century. Discontented Iraqis—whether the beleaguered Shiite majority or the rebellious Kurdish minority—increasingly sought political change through militant means.

In 1936, Iraq had the dubious honor of being the first Middle Eastern state to experience a military coup, an effort aimed in part at the incorporation of Shi'is into the Prime Minister's government. Hashemite rule ended violently in 1958 as a revolutionary regime, one that tried to undercut the privileges of the ruling elite, executed the entire royal family.

Iraq would undergo three more military coups before the Baath party of Hassan al-Bakr and Saddam Hussein seized and consolidated power in 1968.

Baathist Rule, 1968-2003

|

| Baath Party flag. |

Founded in 1940, the Baath Party espoused a utopian political and economic philosophy that should have, in theory, resolved inter-sectarian strife in Iraq. The Baath offered a populist and pan-Arab ideology that privileged individual merit, not communal affiliation.

Developed in the waning days of the colonial era, it is not surprising to find that it has socialist tendencies in which leaders are encouraged to dismantle the existing elite, a class produced by largely European interventions. In practice, as manifested in Iraq, political instability in conjunction with the entrenchment of the Sunni elite did not foster an equitable distribution of power.

It seemed at first that the secular Baath Party would incorporate Shi'is into their government. In the 1960s, 50% of the party’s civilian leaders had been Shi'is. Sunnis, however, who dominated in the military, asserted supremacy in the party after it took power, making it a vehicle for their personal aspirations. Hassan al-Bakr emerged as president, and he appointed his cousin Saddam Hussein as Vice President and head of security operations.

These Baathist leaders favored their own networks of patronage, generating a system of nepotism that allowed members of their family, like the Minister of Defense, who was also Hussein's brother-in-law, to benefit from the spoils of the political victory. By the early 1970s, Shi'is represented no more than 5% of Baath party leaders.

In this way, Baathist rule perpetuated the divide between Shi'is and Sunnis that existed under British and Ottoman rule. It was not that the Baath promoted religious conflict per se, but instead its leaders acted in accord with their desire for greater access to political power and material benefits.

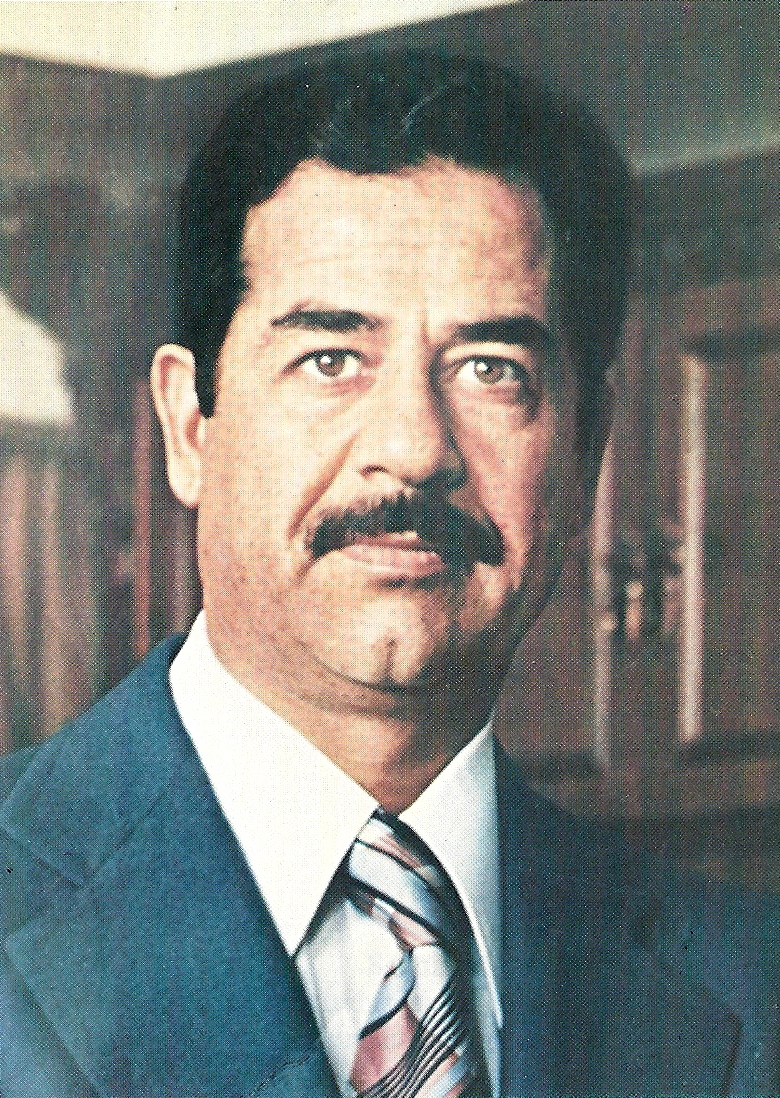

|

| Saddam Hussein, fifth president of Iraqi, circa 1979. |

In response to the uneven distribution of power and resources, many Shi'is began to gather in the mosque to seek solutions in religious texts to their political woes. Disenfranchised Iraqis did not necessarily do so out of a primal need to assert their sectarian identity, but because all secular means of opposition had been closed to them.

The Hashemite monarchy, the revolutionary regimes of the 1950s and 1960s, and now the Baath Party had stamped out political parties, like the once-popular Communist Party, and along with them democratic process.

With no legitimate secular form of political activism, the mosque, a safe haven, became a place where the politically discontent could gather. With the emergence of political Islam in the 1970s and 1980s, Islamic holidays like ashura, when the legitimacy of a ruler can be tacitly called into question, came to be commemorated in Iraq with an ominous fervor by citizens of the south.

The inspiration for this politico-religious revival was the late Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr, the father-in-law of the present-day firebrand cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. He headed the Islamic Call (Dawa) Party. Al-Sadr wanted Iraq to be ruled as a theocracy, not as a secular Baathist fiefdom. Given that so-called Baathist “law” was highly personal and arbitrary, the insistence on Islamic sharia, which is codified and just, held great appeal to many Iraqis.

Once again, events in the eastern state of Persia, now Iran, contributed to the fate of Shi'is in Iraq.

In 1979, the highly secular Iran experienced a Shi'i Revolution to create the Islamic Republic of Ayatollah Khomeini, and the Iraqi Baath was no longer content merely to ignore Shi'i interests in their country; its leaders began to actively destroy them. On ashura in the very year of the Iranian Revolution, Iraqi troops marched on Karbala and arrested the young men who passionately paraded to the shrine of Imam Husayn.

| Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Iraq. |

Wars with foreigners allowed the Baath to justify its marginalization of Shi'is.

The Iran-Iraq War was fought between 1980 and 1988, and it led to the deaths of as many as 1 million people. Just as during Ottoman times, the government of Iraq proved suspicious of its Shi'i subjects who, it feared, might prove loyal to clerics in Iran. So, the Baath terrorized Shi'is. In one case, Saddam Hussein exiled of 250,000 Iraqi Shi'is whose loyalties were ostensibly to the enemy nation.

Similarly, the Persian Gulf War of 1991 also provided the Baath with an excuse for stamping out unrest and further marginalizing Shi'is in Iraq's southern regions. During this conflict, disillusioned Shi'is took over the holy cities of Karbala and Najaf, thereby expressing their rejection of a regime that had caused them distress. Using armed helicopters, the Baath put down the revolts in the south. In doing so, the Iraqi government killed 100,000 Iraqi civilians.

Finally, there was the Iraq War, which ended the Baath’s reign in 2003. Much like the British occupation after World War I, this conflict heightened sectarian tensions rather than neutralizing them. The United States fought this war in part to bring democracy to the Middle East, and yet its administrators enacted policies that in retrospect clearly facilitated the organization of political groups according to communal interests, not civic ones.

L. Paul Bremer, who administered the Coalition Provisional Authority during the first year of the occupation, formed a 25-person Iraqi Governing Council (IGC) in July 2003. The IGC consisted of 13 Shi'is and five Arab Sunnis. These actions reproduced a society in which affiliation to a communal group, not democratically inclined political leanings, determined access to power.

|

| Members of the U.S. Army pose under the "Hands of Victory" sculpture in Baghdad, Iraq during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, November 2003. |

In his memoir, Bremer laughingly dismisses the one appointee who represented a political party, a Communist denigrated as a 1970s throwback. The IGC ensured that access to power was once again determined by ethnic and sectarian identity, and so a civil war soon broke out between Shi'is and Sunnis in Iraq.

The political dynamics in Iraq, and the supremacy of Sunni interests over a more collective sense of nationhood have proved remarkably consistent from the Ottoman Empire to the present.

ISIS and Iraq

|

| Nouri al-Maliki. |

In 2006, Nouri al-Maliki became Prime Minister of Iraq, and he remained in this post until summer 2014. For some Iraqis, it may have seemed that the injustices of the past—those begun under Ottoman rule—were finally righting themselves. Al-Maliki is a Shi'i who had been a member of the Islamic Call Party since the 1970s, and so had been an important oppositional voice against the Baath. Thus, he was a former dissident with a strong sense of his Shi'i identity.

Al-Maliki's administration, however, did not lead to a new equilibrium in Iraqi society, but instead to a determined Shi'i effort to avenge past wrongs by disadvantaging Sunnis. On 16 August 2014, The Economist noted, “Some Sunnis came to support the extremists of IS [ISIS], seeing them—often reluctantly—as the only defence against a brutal security apparatus.”

In Iraq, the Islamic State is the most recent and most awful manifestation of a historic struggle between Sunnis and Shi'is for economic and political power, which dates to the Ottoman era.

The rise of the Islamic State as an aberrant entity in the midst of a long-standing state provides tangible evidence of the conclusion of Yara Badday, an Iraqi-American who is the daughter of a Shi'i father and a Sunni mother. She writes that “cultural differences themselves are not the cause of violent conflict, but rather the glaring inequalities over political power, land, and other economic assets.”

Badday's statement encourages readers interested in the conflict and Iraq—as well as tensions elsewhere in the Middle East—to look beyond simple analyses that rely heavily on religiously infused understandings of behavior.

After all, and as seen in Iraq over the past century or more, the rhetoric of religiosity all too often conceals more mundane manipulations by political actors pursuing their worldly desires for power and treasure.

Abdullah, Thabit. A Short History of Iraq: from 636 to the Present. London: Longman, 2003.

Bashkin, Orit. The Other Iraq: Pluralism and Culture in Hashemite Iraq. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Batatu, Hanna. The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movement in Iraq. (reprint, 1978) London: Saqi Books, 2004.

Bernhardsson, Magnus Thorkell. Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation Building in Modern Iraq. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

Davis, Eric. Memories of State: Politics, History, and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq. London: University of California Press, 2005.

Dawisha, Adeed. Iraq: a Political History from Independence to Occupation. Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Dodge, Toby. Inventing Iraq: the Failure of Nation-Building and a History Denied. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

Ghareeb, Edmund. Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2004.

Hala, Fattah. A Brief History of Iraq. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008.

Marr, Phebe. The Modern History of Iraq. USA: Westview Press, 2003.

Nakash, Yitzhak. Shiis of Iraq. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Robertson, John. Iraq: A History London: OneWorld Publications, 2015.

Shields, Sarah. Mosul Before Iraq: Like Bees Making Five-Sided Cells. New York: State University of New York Press, 2000.

Sluglett, Peter and Marion Farouk Sluggett. Iraq since 1958: from Revolution to Dictatorship. London: KPI, 1987.

Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.