On October 29, 1914, the Goeben and Breslau—a pair of battleships that together constituted the Mediterranean division of the German Imperial Navy—opened fire on a Russian gunboat and a mine-laying vessel. The sinking of two Russian ships by a German taskforce under the command of a German admiral improbably marked the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the First World War. Within a week, the Ottomans were at war with three great powers (and the vast empires under their control). The continued survival of the Ottoman Empire, which in 1914 had stood for over six-hundred years, hinged on the military fortunes of Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The general outline of the First World War in the Middle East is relatively well-known. Movie-going audiences are familiar with the dashing exploits of T. E. Lawrence as depicted in the Academy Award winning film, Lawrence of Arabia. Numerous historical works have been written which examine events from the perspective of the victorious powers.

Relatively few historians, however, have attempted to depict the course of the Great War from the Ottoman perspective. The reasons for this, as Eugene Rogan suggests in The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East, are fairly simple. In the first place, according to Rogan, very few western historians possess the language skills necessary to read the wide range of available primary sources. Furthermore, the Turkish government severely restricts access to the materials held in the Turkish Military and Strategic Studies Archive in Ankara. The Fall of the Ottomans seeks to remedy this imbalance to some degree, providing a synthesis of recently published secondary research on the Ottoman involvement in the First World War. Drawing on a range of recent works, as well as a narrow selection of archival sources, Rogan’s study is intended to help “restore the Ottoman front to its rightful place in the history of both the Great War and the modern Middle East” (xvii).

The Ottoman Empire’s earliest campaigns in the First World War, as Rogan explains, met with unqualified disaster. An attempted encirclement of Russian forces in the Caucasus Mountains (in the depths of winter)—organized by the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver Pasha—failed spectacularly. Likewise, an ambitious bid to seize the Suez Canal from the British achieved very little. By the spring of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had fallen on the defensive.

It soon faced an existential threat in the form of the Anglo-French operations in the Dardanelles, the narrow strait dividing the Aegean Sea from the Sea of Marmara (and hence from the Ottoman capital of Constantinople). The Gallipoli campaign, as it became known, was one of the largest amphibious operations ever attempted. British and French soldiers, together with sizeable contingents from the British Dominions, landed on the Gallipoli peninsula with the goal of overcoming the Turkish defenses blocking naval access to the Black Sea.

|

| Dominion soldiers on the beach of ANZAC Cove, one of the principle Entente landing sites on the Gallipoli peninsula |

Rather than quickly driving the Ottoman defenders from their positions, the allied force quickly became mired in trench warfare that was comparable to the fighting on the Western Front. Repeated attacks failed to dislodge the Ottoman defenders, and the allied force was ultimately compelled to withdraw. Shortly after the conclusion of the Gallipoli campaign, the Ottoman Empire achieved even greater military success in Mesopotamia. Ottoman forces isolated and destroyed an exhausted and overextended Anglo-Indian division under the command of Major-General Charles Townshend. The surrender of 13,000 soldiers at the Iraqi city of Kut was unprecedented in British history. The hopes that allied strategists once entertained of knocking the Ottoman Empire out of the war with a single decisive blow seemed increasingly unrealistic.

Faced with a string of major setbacks, the British and their allies were willing to explore a variety of unorthodox strategies aimed at undermining the Ottoman Empire. Foremost among these was support for the nascent Arab Revolt, which was headed by the rebellious Sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali. Tapping into Arab nationalist dissatisfaction with Turkish rule, the British hoped to undermine the foundation of Ottoman power in the Middle East. They furthermore hoped to reduce the religious authority of the Ottoman Sultan, who – as the holder of the Sunni Caliphate – had called for a worldwide jihad against the Entente powers. By aligning themselves with the Sharif of Mecca—a direct descendent of the Prophet Muhammad—British leaders believed that they could placate their empire’s vast Muslim population and defuse the threat of a religious violence.

British support for the Arab Revolt proved remarkably successful. Advised by a small contingent of British Army officers, including the archaeologist-turned-intelligence-agent T. E. Lawrence, Hussein and his followers successfully seized many of the major cities in the Hejaz—Arabia’s Red Sea coast. At the same time, the British undertook large-scale operations aimed at removing the Ottoman threat to the Suez Canal. Working in concert, the British and the Arabs ejected the Ottomans from Jerusalem and its environs by the end of 1917. Ottoman counterattacks achieved little. British forces under General Edmund Allenby, together with the Arab rebels commanded by Emir Faysal (Hussein’s son and the future king of Iraq), stormed northwards, occupying Damascus in October. The Ottoman government collapsed and sued for peace shortly thereafter.

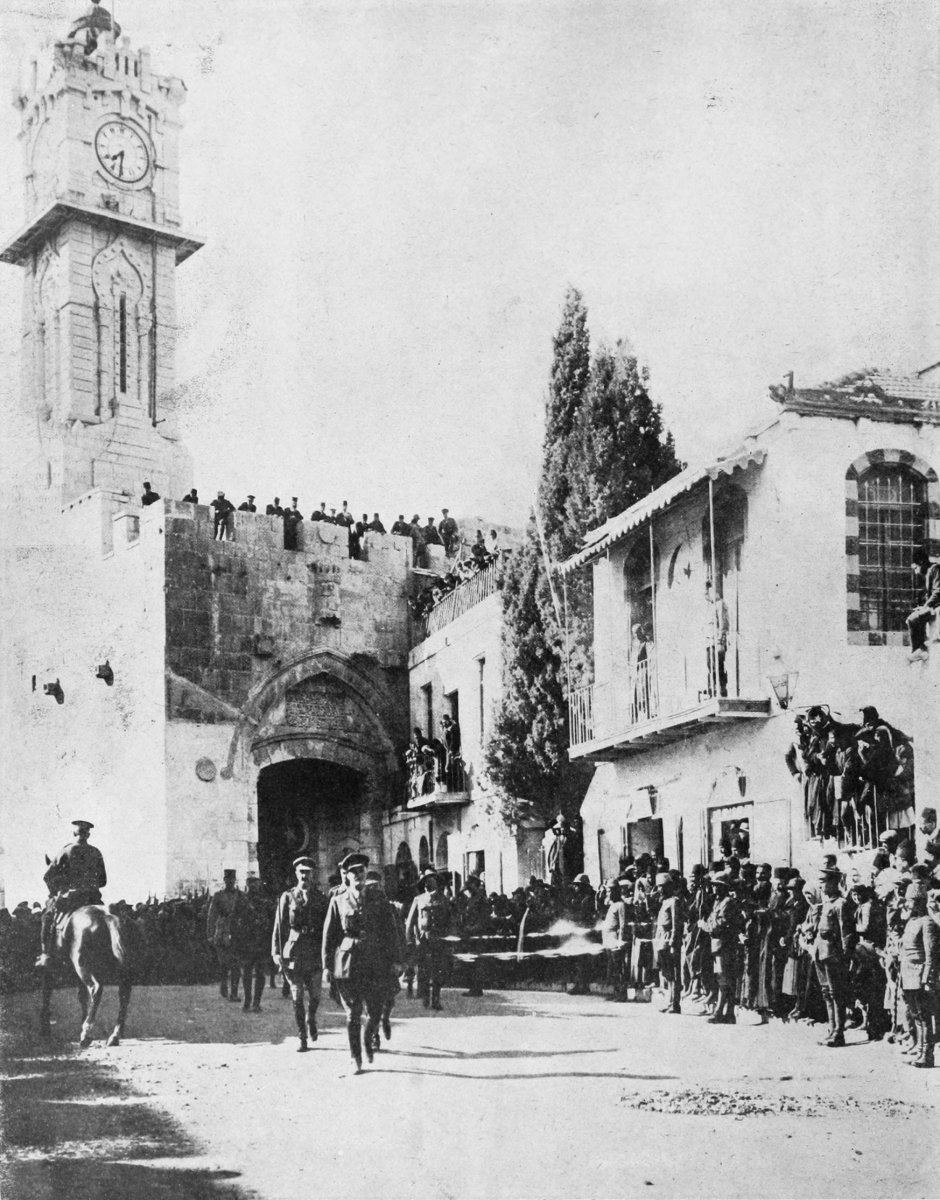

|

| General Edmund Allenby entering Jerusalem on December 11, 1917. Allenby dismounted as a sign of respect for the holy city. |

Rogan’s account of Ottoman experience in the First World War is competently written and—for the most part—comprehensive. Rogan’s narrative is peppered with eyewitness accounts taken from a range of published memoirs written by soldiers on both sides of the conflict, although there is very little material taken directly from archival sources. His work follows a strictly chronological narrative; there is little in the way of sustained analysis or argumentation. The few arguments that Rogan does advance nevertheless merit attention.

In the first place, Rogan suggests (reasonably) that the Ottomans were by no means predestined to fight in the First World War on the side of the Central Powers. On the contrary, the Ottoman government proposed to enter into an alliance with Russia even after the outbreak of fighting in Europe in early August. The Young Turks, while misguided in many respects, apparently recognized the Ottoman Empire’s very real military, economic and industrial limitations, and sought to enter the war only under the most favorable circumstances.

With regard to the British conduct of the war, Rogan argues that Winston Churchill has often received a too-large share of the blame for the Gallipoli fiasco. The responsibility for the failure of the Dardanelles expedition, in Rogan’s estimation, rests mainly on the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener. While there is some truth to this, it is nevertheless undeniable that the Admiralty must bear a large share of the blame for what was originally envisioned as a purely naval campaign.

Finally, students of modern Middle Eastern history may be interested to learn that Sykes-Picot agreement, according to which the Ottoman Empire’s Arab territories were divided into British and French spheres of influence, did not create the borders of the modern Middle East. Indeed, as Rogan argues, “the map as drawn by Sykes and Picot bears no resemblance to the Middle East today” (286).

|

| Enver (center) and Wilhelm (second from left) survey the battlefield of Gallipoli in 1917. The Ottoman Empire may have been a net drain on the German war effort. |

Although Rogan’s narrative is generally excellent, the author nevertheless misses several opportunities to deal with comparatively neglected (yet still important) elements of the history of the Ottoman Empire’s role in the First World War. Most notably, Rogan devotes remarkably little attention to the Russo-Turkish conflict in the Caucasus, despite the fact that this theater was undoubtedly central to the Ottoman war effort. Rogan instead emphasizes campaigns that have already received substantial attention in English-language historiography, including the Dardanelles expedition and the Arab Revolt. Additionally, Rogan provides few details concerning the Ottoman Empire’s relations with its European allies. The Ottoman Empire’s place within the Central Powers is itself a fascinating topic that has too often been overlooked.

While The Fall of the Ottomans does not include every possible detail about an (admittedly vast) topic, it nevertheless provides a useful and extremely readable guide to the course of the First World War in the Middle East. Rogan’s volume serves as an admirable starting point for anyone seeking to better understand the Ottoman Empire’s participation in the First World War.