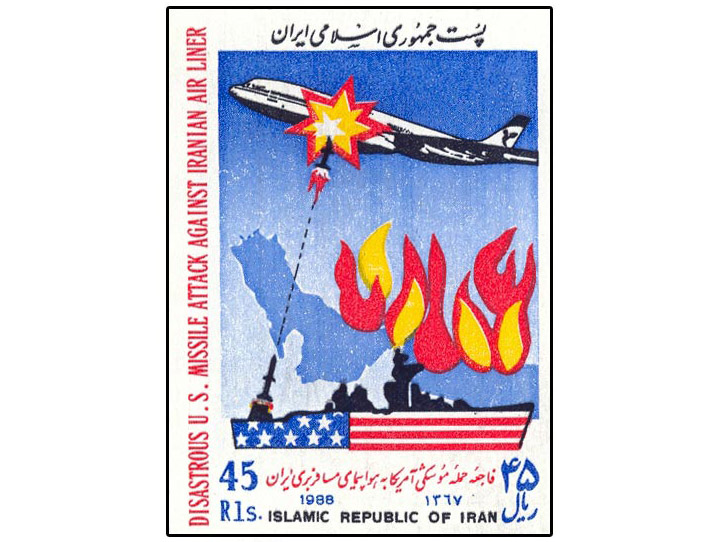

This Iranian postage stamp commemorates the shooting down of a commercial passenger flight, Iran Air 655, by a U.S. Navy cruiser in 1988. The memory of the history of foreign intervention in Iran casts a long shadow on its current relationship with the United States.

Since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and the taking of American hostages that year, Americans have tended to see the Iranian regime as dangerous, reckless and irrational. Recent concern over Iran's nuclear ambitions and anti-Israel declarations have only underscored the sense many Americans have that Iran is a "rogue" nation, part of an "axis of evil." There is another side to this story. This month historian Annie Tracy Samuel looks at American-Iranian relations from the Iranian point of view, and adds some complexity to the simplified story often told.

Read more on Iran and the Middle East: U.S.-Iranian Relations, Syria's Islamic Movement; U.S.-Iraq Relations; Turkish Politics; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide, and The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

The victory of moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani in Iran’s June 2013 presidential elections generated hope that the thirty-year standoff between Iran and the United States might be resolved.

During his first press conference after being sworn in as president, Rouhani declared that he was open to direct talks with the United States, while a White House statement released after Rouhani’s inauguration offered him a “willing partnership.”

Those conciliatory words, however, were accompanied on both sides with qualifications, skepticism, and antagonistic gestures. Congress continued to push new sanctions aimed at curbing Iran’s nuclear ambitions, and the Obama administration conditioned any partnership on Iran taking steps to meet its “international obligations.”

On the Iranian side, Rouhani emphasized that the United States must take “practical step[s] to remove Iranian mistrust” before he would be willing to engage in dialogue. His focus on Iran’s mistrust is not simply rhetoric but reflects what Iran sees as the long history of U.S. enmity.

While Americans understand relations with Iran in terms of its nuclear program and incendiary anti-Israel homilies, Iranians see the relationship as part of a long and troubling history of foreign intervention and exploitation that reaches back into the nineteenth century. Iranian leaders argue that if interactions between Iran and the United States are to improve, this history will have to be addressed and rectified.

The past is very much part of the present in Iran. A profound consciousness of history informs Iran’s political and strategic outlook, its conception of itself and its position in the world, and its non-relationship with the United States.

As both sides cautiously explore today’s opportunities to reset their fraught relationship, American policy-makers should take note of how Iran perceives the history of its relations with the United States, particularly the U.S. role in the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88.

The Legacies of European Imperialism

Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, Great Britain and Russia fell upon the country then known as Persia in their contest for imperial and economic domination. Though Persia promised different things to the different powers—control of the Caspian Sea and the long-sought warm water port for Russia; security of India for Britain—they sought to achieve their goals by weakening and controlling the country.

After several decades of invasion and imposed stagnation, combined with the profligacy and incompetence of Persia’s Qajar shahs, Britain succeeded to a large extent in doing both. In two separate concessions granted in 1872 and 1891, British citizens secured monopolies over almost all of Persia’s financial and economic resources.

According to British Foreign Secretary George Curzon, this was “the most complete and extraordinary surrender of the entire industrial resources of a Kingdom into foreign hands that has probably ever been dreamt of, much less accomplished, in history.”

Neither concession was fulfilled, however.

In some of the earliest instances of successful popular protests in the Middle East, Iranians rallied against the measures and eventually forced their cancellation.

The movements united the Iranian nation and paved the way for the Constitutional Revolution of 1906. Having witnessed the shah’s penchant for selling off the country to foreign powers, Iranians forced him to create a legislative assembly (Majlis) and grant a constitution.

In Iran, then, the history of foreign intervention is bound together with a tradition of popular protest and defense of the nation. And this pattern repeated several times in the twentieth century.

During World War I, Iran declared neutrality but became a battlefield for the European belligerents nonetheless. Following the ceasefire, Great Britain took advantage of the weakened and sundered country to impose a highly unfavorable treaty that essentially turned Iran into a British protectorate.

Once more, however, the increase in foreign intervention generated a movement for national independence, which culminated in the suspension of the agreement, the ouster of the Qajar dynasty, and the establishment of the Pahlavi monarchy in 1925.

During the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi (1925-41), outside interference in Iran became much less direct. Until World War II his government was able to maintain a level of independence unprecedented in the country’s modern history.

Then, in 1941 the Allied Powers decided the sitting monarch’s pro-German sympathies and weak defenses were an intolerable threat. Led by Great Britain and the Soviet Union, they invaded Iran, forced Reza Shah to abdicate, and placed his young son on the throne.

Enter the United States

Like his abrupt rise to power, Mohammad Reza Shah’s reign owed much to the contrivances and support of foreign powers. In particular, the coronation of the second and last Pahlavi Shah was accompanied by the appearance of the United States as an important player in Iranian affairs.

Although America’s interest in Iran came comparatively late, Iranians view it as part of the longer history of foreign exploitation.

During the first decade of Mohammad Reza’s rule, social conflicts, economic problems, and foreign interference were acute. Together these crises generated demands for political and economic change and a powerful nationalist movement in the Majlis (parliament).

One of the main demands was for the revision of Iran’s concession to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), which exploited the country’s oil wealth. After negotiations with the AIOC produced a highly unfavorable supplementary agreement in 1949, opposition to the company and to Iran’s subservience to foreign interests intensified, leading to popular demonstrations and, in March 1951, to the nationalization of the oil industry.

The nationalization efforts in the Majlis were led by Mohammad Mosaddeq, a veteran politician committed to freeing Iran from imperial domination.

As premier, Mosaddeq worked to curb the power of the shah, particularly over the armed forces. He refused to relinquish Iran’s control of its oil, and he allowed the Communist Tudeh Party, which had grown in popularity with the rise of anti-Western sentiment and which supported Mosaddeq (at this time), to operate more openly.

Opposition to Mosaddeq’s rule grew in the United States and Britain, which viewed the premier’s intransigence as the primary obstacle to procuring a new oil concession. In the context of the Cold War, Mosaddeq was portrayed in the Western countries as moving dangerously close to the Soviet Union.

In August 1953, therefore, British and American agents successfully engineered Mosaddeq’s overthrow and restored the shah’s control of the country.

To this day, Mosaddeq stands as a symbol of Iran’s nationalist ambitions and the role of outside powers in extinguishing them. His legacy is commemorated annually on 29 Isfand and on 28 Murdad, the dates on the Iranian calendar that correspond to the nationalization of the oil industry in 1951 and the overthrow of Mosaddeq in 1953, respectively.

Iranians brandished his portrait when they demonstrated against the shah in 1978-79, and they did so in 2009 when they collectively called out to their potentates, “Where is my vote?” The fact that the leaders of the Islamic Republic also extol Mosaddeq as a martyr of imperialism is testament to the broad significance of his legacy.

A monograph published by a government agency in the early 1980s illustrates how Iranians view the role of the United States at this turning point in their modern history.

The 1953 coup removing Mosaddeq, the book asserts, was “executed by the direct intervention of the U.S., [and] imposed once again the Shah over the Iranian nation. There followed a dictatorial monarchy which would repress and oppress the nation for the twenty-five years to come. The Shah had no chance to return without the coup; he had also no chance of sustaining his faltering regime without military and financial support from America.”

The Shah: America’s Friend in Tehran

Once back in power with the support of the United States, Mohammad Reza Shah devoted his energies towards two ends: preserving his power and regime; and yanking Iran into the modern world. The shah equated modernization with Westernization and secularization, and to make Iran modern he sought support from American officials and advisors, encouraged American investment, imported American goods, and purchased loads of American weaponry.

In 1964, for example, the Majlis, now less independent, passed one bill to grant diplomatic immunity to American military advisors and a second authorizing a $200 million loan from the United States for the purchase of military equipment.

The bills were “publicly and strongly denounced” by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a leader of the opposition against the shah and the future leader of the revolution that would overthrow him. Khomeini characterized the measures as “signs of [Iran’s] bondage to the United States.” After his attack was published and circulated as a pamphlet in 1964, the shah exiled Khomeini from Iran.

In subsequent years, the shah ruled through repression and violence and employed his internal security organization, SAVAK, which received aid from the CIA, to jail, torture, or kill those who opposed his rule. He enriched and empowered a small, Westernized elite, which became increasingly alienated from the rest of Iranian society.

By 1978, those outside the small aristocracy bore manifold, if differing, grievances against the shah’s rule—a regime that had been made possible by U.S. support, carried out with U.S. wealth and weaponry, or modeled on U.S. culture. As the vast majority of Iranians grew more anti-shah, therefore, they also grew more anti-American.

The 1979 Revolution and the Great Satan

As a result of the United States’ support for the shah, the Iranians who opposed his reign and took part in the revolution that overthrew him in 1979 made diminishing American power a key part of their platform.

In the first months of the Islamic Republic, Iran’s relations with the United States were a subject of debate in Tehran, with some favoring the maintenance of normal, though less substantial, relations and others favoring severing all ties with Washington.

The Carter administration’s decision to admit the shah into the United States for medical treatment in October 1979, however, gave credence to the latter group’s contention that the United States was actively working to subvert the new regime.

It also led to the event that continues to shape U.S. views of the Islamic Republic: the occupation of the American Embassy in Tehran by supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini, during which they held hostage the Americans they found inside for 444 days. (The 2012 Academy-Award-winning film Argo is the most recent revisiting of these events in American culture.)

Almost immediately, the takeover of the embassy became a potent and lasting symbol in Iran of the revolution’s determination to confront and curtail U.S. involvement.

In 1980, the Islamic Propagation Organization, a new government agency, published Fall of a Center of Deceit, “a report on the crimes of the Great Satan (The United States) in Iran and on the fall of the espionage center, prompted by the Muslim students following the line of Imam Khomeini.”

It describes how these “revolutionary students took the initiative to occupy the American Embassy, or rather, the American spy den,” with “clear and definite” objectives: “put an end to spying and sabotage activities, stop American interventions in Iran’s domestic affairs, force the extradition of the Shah and recuperate funds stolen from the Iranian nation by the criminal Pahlavi family.”

The book includes pictures and excerpts from documents found in the embassy, including a torn-up portrait of a grinning President Carter with the caption “no more smile for you Mr. Oppressor.”

Like the nationalization of the oil industry and the coup against Mosaddeq, the takeover of the embassy is celebrated annually in Iran, and is used as an occasion to reinforce the image of the United States as a foreign oppressor.

On the 33rd anniversary of the event in 2012, Mohammad Reza Naqdi, the commander of Iran’s paramilitary Basij force, addressed the crowd assembled outside the embassy and called the United States “criminal” and “the worst [regime] on earth.”

The leader of Friday prayers in Tehran also addressed the crowds and described the importance of the event: “The first thing that our revolution did was to crush the prestige of the United States in the world and … nullified all the values … which the United States was propagating.”

The Iran-Iraq War

Like the embassy takeover, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) is viewed in Iran as part of its struggle against the United States.

Unlike the hostage crisis, however, the Iran-Iraq War does not arouse strong emotions among Americans, if it is remembered at all. Most are unfamiliar with both the direct involvement of the United States in the conflict on the side of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and with the extent to which the war shapes Iranians’ views of the United States today.

The Iran-Iraq War began in September 1980 when Iraq invaded Iran. Relations between the neighbors—who have a long history of animosity—had steadily worsened since the establishment of the Islamic Republic.

Aside from a few dramatic turns—particularly Iran’s expulsion of Iraqi forces and its invasion of Iraq in 1982—the eight-year war was dominated by and concluded in stalemate.

Though the figures are highly uncertain, estimates suggest that the war caused hundreds of thousands of casualties and severe damage to Iran’s economy and infrastructure. The conflict was particularly brutal because of Iraq’s use of chemical weapons and airstrikes on civilian population centers and major cities.

Over the past thirty-three years, both during and after the war, Iranian leaders and publications have consistently emphasized that U.S. support for Iraq demonstrates its determination to confront and contain the Islamic Republic. And they have disseminated a historical narrative of the war as a foreign-backed and existential assault on Iran. The way Iran refers to the conflict—as the Imposed War or Sacred Defense—demonstrates its significance.

According to this narrative, the Iraqi invasion was directly tied to U.S. opposition to the revolution, and to the revolution’s opposition to the United States. During the war, emphasizing American involvement served to rally support for the war effort by heightening the stakes of the conflict.

For example, Passage of Two Years of War, a book published in 1983 by the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), the powerful military organization charged with defending the Islamic Revolution and Republic, characterizes “Saddam’s Imposed War against our revolution, which occurred with the funding and management of America, [as] a sign of the power of this revolution. [The war] is presenting a new way to confront all those who share the hope of defeating the Islamic Revolution.”

It goes on to describe how the war allowed the Islamic Republic to identify and defeat its enemies: “During this war the villainous faces of all the American mercenaries have become known and their masks of deception and lies have been permanently removed. Our nation has become fully united knowing that the leaders of evil and blasphemy and the adherents of the Great Satan will be completely destroyed.”

Iranian histories written after the end of the war also contain that narrative, though Iran’s confrontation with the United States is usually described in political and economic, rather than religious or ideological, terms.

For example, a book on the war published in 2001 by the IRGC describes the beginning of the war in this way: “The Islamic Revolution of Iran clearly announced its opposition to the domination of the two great powers, particularly America. … The idea that the Islamic Revolution and its spread would endanger the interests of the West all over the world and especially in the Middle East deprived America and its allies of serenity.”

Today, Iranian leaders describe the war in the same manner. Major General Yahya Rahim Safavi, former commander of the IRGC and current senior advisor for military affairs to Supreme Leader Khamenei, said in an interview on the anniversary of the Iraqi invasion in 2007, “Western powers, which were worried about the influence of the Islamic Revolution on regional Arab countries, encouraged Saddam to attack Iran.”

Similarly, in 2004 an IRGC spokesman stated, “It is well documented that Saddam was the aggressor in the war against Iran, but it was the great powers, particularly the United States, which guided Saddam.”

While the perception of the United States urging Saddam to invade Iran does not reflect the historical record, Iranian contentions regarding U.S. backing of Iraq and its impact on the course of the war are well-founded.

After the invasion, the United States actively aided the Iraqi war effort. Along with other countries, it provided Iraq with extensive diplomatic, economic, and military support. Iranian leaders often describe how, with the help of the United States, Saddam Hussein was “armed to the teeth.”

They also argue that the development of their weapons programs—and their desire to protect themselves from outside domination—developed from the unfavorable position in which they found themselves during the Iran-Iraq War.

Almost every article on Iran’s military achievements that appears on Fars News, a website affiliated with the IRGC, notes that Iran “launched an arms development program during the 1980-88 Iraqi imposed war on Iran to compensate for a US weapons embargo.”

The articles also stress that Iran’s efforts to expand its defensive capabilities should not be viewed as a threat to other countries but are the product of the lessons learned during the war and are intended to prevent an attack like the one that initiated the conflict.

In addition to helping Iraq maintain its military superiority, in 1987 the United States moved its naval forces into the Persian Gulf to support Iraq and protect oil tanker traffic. The move led to direct confrontations between Iranian and American forces, which lent credence to the belief that the United States was leading the charge to defeat the Islamic Republic and that Iraq was merely its pawn.

After one encounter in October 1987, in which an attack by the United States on Iranian patrol boats killed three sailors, an IRGC commander stated, “The best response to America is to continue the war because Saddam’s fall means an end to all wishful hopes of America in the region.”

In October 2011, at a ceremony to honor the Iranians killed in that attack, the commander of the IRGC Navy, General Ali Fadavi, stated, “During the Sacred Defense we were defending against the Iraqis who were the endpoint of the arrow of world arrogance (the US), but in the last [year] of the war, we were in vast and direct confrontation with the Americans in the Persian Gulf.”

While Iranians saw the United States’ active involvement in the Gulf as proof of U.S. hostility, they viewed its latent support for Iraq—the refusal to name Iraq as the aggressor or to condemn its use of chemical weapons in the war—as particularly caustic evidence of American malevolence. Iranian statements after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq tend to point out the hypocrisy of the United States in supporting and then ousting Saddam Hussein.

Iranians continue to suffer from the effects of chemical weapons used against them during the war, which, along with the bodies that continue to be unearthed and the mines that still explode along the border, are powerful reminders of the horrors of the conflict.

Iranian leaders assert that U.S. involvement in the war in support of Iraq prevented Iran from attaining victory. According to an IRGC publication, Iran’s advances in Iraq after 1982 shifted the political and military balance of the war in Iran’s favor. In response, the United States again increased its support for Iraq, which allowed Iraqi forces to retake the territories Iranian forces had occupied.

Ultimately, according to the same source, the continuation of Iraqi offensives, the fear that Iranian cities would be attacked by chemical weapons, and the shooting down of an Iranian passenger airplane by the United States, killing the 290 people onboard, “placed the Islamic Republic in a difficult position for which it had no appropriate measures to overcome” and forced it to announce its agreement with U.N. ceasefire resolution 598 on July 18, 1988, which ended the war.

A War without End

Even though the Islamic Republic was prevented from winning a decisive victory, Iranian leaders emphasize that the country grew stronger through its experience in the war and celebrate the Sacred Defense as a source of Iran’s current power.

This assertion reflects an effort to transform the conflict from an unfortunate consequence of the Islamic Revolution into a blessing that ensured its success.

It also reflects the idea that the United States failed to curb the power of the Islamic Republic in the war.

In the words of former IRGC commander Yadollah Javani, “All [enemy plots against Iran] ended in failure. A clear example of that was the [Iraqi] imposed war. … The enemy believed it could defeat the Islamic Revolution through war, but it was the Iranian nation which emerged victorious.”

However, in this view, the Islamic Republic’s victory in the war did not lessen the determination of its enemies to confront it. As a result, the war is ongoing, and the Sacred Defense continues.

During a May 2011 conference for veterans of the war, IRGC commander and head of the armed forces social security organization Hossein Daqiqi declared, “The war has still not ended, and today the enemies are waging a soft war against Iran.”

Similarly, in 2010 former IRGC commander Safavi asserted, “Certain countries, with the United States in the lead, which could not realize their hostile plot against Iran during the 1980-1988 war with Iraq, are making efforts to create problems for the Islamic Republic” today.

The idea that the war is still being imposed on Iran reflects the way Iranians tend to bind together in the face of a common enemy. Indeed, for much of the eight years that the war with Iraq was actually being waged, a divided Iranian population did come together to confront the external aggressor.

In a manner not unlike that of other revolutionary states, the Islamic Republic has used the threat of foreign aggression and a focus on past injustice to forge support for the government and to unite the people under its mantle.

The Past and the Way Forward

The notion that the war is ongoing also demonstrates the importance of understanding current events in Iran in historical perspective. In Iran, the past is part of the present because the past is unresolved. Iranians are not satisfied with the past, have not come to peace with the past, and so have a need to keep the past open and alive in the hope that by doing so it can somehow be dealt with, improved, and settled.

Though reestablishing relations between Iran and the United States will, of course, require much more, appreciating how the other side views history can contribute to that goal.

Iranian leaders make that point explicitly. A foreign ministry spokesman said in November 2012, “The Islamic Republic of Iran believes that only respect for the rights of the Iranian nation, as well as a fundamental and practical reconsideration of the US government’s wrong policies in the past could reduce the Iranian nation’s distrust towards the US administration.”

The Supreme Leader has also emphasized the bitter legacy of the United States’ past interactions with Iran—overthrowing Mosaddeq, buttressing the shah, and supporting Saddam in the Iran-Iraq War in particular—and their continued importance in Iran today.

Too often this history is either forgotten or relegated to the past, when in fact its bearing on the present could not be more fundamental to any resolution to the U.S.-Iranian standoff.

Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982).

Ali M. Ansari, Confronting Iran: The Failure of American Foreign Policy and the Next Great Crisis in the Middle East (New York: Basic Books, 2006).

Anthony H. Cordesman, The Lessons of Modern War, Vol. II The Iran-Iraq War (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991).

Darioush Bayandor, Iran and the CIA: The Fall of Mosaddeq Revisited (New York: Palgrave, 2010).

James A. Bill, The Eagle and the Lion: The Tragedy of American-Iranian Relations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988).

James G. Blight, et. Al. Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979-1988 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2012).

Shahram Chubin and Charles Tripp, Iran and Iraq at War (London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 1988).

David Crist, The Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran (New York: Penguin Press, 2012).

Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, eds., Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2004).

Bryan R. Gibson, Covert Relationship: American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988 (New York: Praeger, 2010).

Dilip Hiro, The Longest War: The Iran-Iraq Military Conflict (London: Grafton Books, 1989).

Iranian Studies 45.5 (2012).

Efraim Karsh, ed., The Iran-Iraq War: Impact and Implications (Houndmills: The MacMillan Press, 1989).

Nikki R. Keddie, Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror (Hoboken: J. Wiley & Sons, 2003).

John W. Limbert, Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press, 2009).

David Menashri, Iran: A Decade of War and Revolution (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1990).

Abbas Milani, The Myth of the Great Satan: A New Look at America’s Relations with Iran (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2010).

Kenneth M. Pollack, The Persian Puzzle: The Conflict between Iran and America (New York: Random House, 2004).

Lawrence G. Potter and Gary Sick, eds., Iran, Iraq, and the Legacies of War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Barry Rubin, Paved with Good Intentions: The American Experience and Iran (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980).

Gary Sick, All Fall Down: America’s Tragic Encounter with Iran (New York: Penguin Books, 1986).