When evangelist Billy Graham died earlier this year he was eulogized as "America's Pastor." But as historian Melani McAlister shows us this month, Graham set in motion forces that have made American fundamentalism more diverse, helped bring it into the American mainstream, and ultimately facilitated its growth internationally as well.

When Billy Graham died in February of this year, many of the tributes referred to him as “America’s Pastor”—and as the person who had preached the Christian gospel to more people than anyone else in history.

But as a number of people pointed out, he represented primarily an older, largely white and conservative tradition of Protestantism. For the nation’s Catholics, liberal Protestants, Muslims, Hindus, and Jews who make up the majority of Americans today he was hardly “America’s” pastor. Nevertheless, when he died his body lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

Graham did have an outsized influence on preaching styles and on the development of celebrity preaching in the United States and abroad. During his heyday in the 1950s through the 1970s, he was a household name. He led numerous mass preaching events (he called them “crusades” until the 1990s) across the United States and in Europe, Africa, and Asia. In 1973, Graham preached the gospel to one of the largest live crowds ever, 1.1 million people, in Seoul, South Korea.

Graham once said that he was “not a great preacher” and it’s true that he wasn’t particularly educated in theology; Graham’s sermons were simple and straightforward. Still, as a preacher, Graham was a master of the classic gospel call to repent and be saved. He understood that great preaching is about connection—about reaching out to a broad array of people but finding them at the personal level. And it is about right timing: not necessarily saying what people want to hear, but knowing how to speak to the moment in which they live.

Graham preaching in Oslo, Norway in 1955 (left), in Glasgow, Scotland in the 1950s (right), and in Britain in 1967 (bottom).

In so doing, he shaped preaching indelibly in his lifetime and the modes of outreach that he helped to perfect have significantly influenced preaching in the decades since. Three important components of Graham’s outreach in particular were influential for the following generations: crusade-style preaching, the use of media, and establishing interaction with his followers.

In the past 30 years, a range of evangelical ministries have built upon and adapted his methods. In the process, they have transformed evangelicalism, making it more international, more racially diverse, and more attentive to women’s concerns. Perhaps more than any other figure in the postwar era, Billy Graham reshaped the practice and experience of American Protestantism.

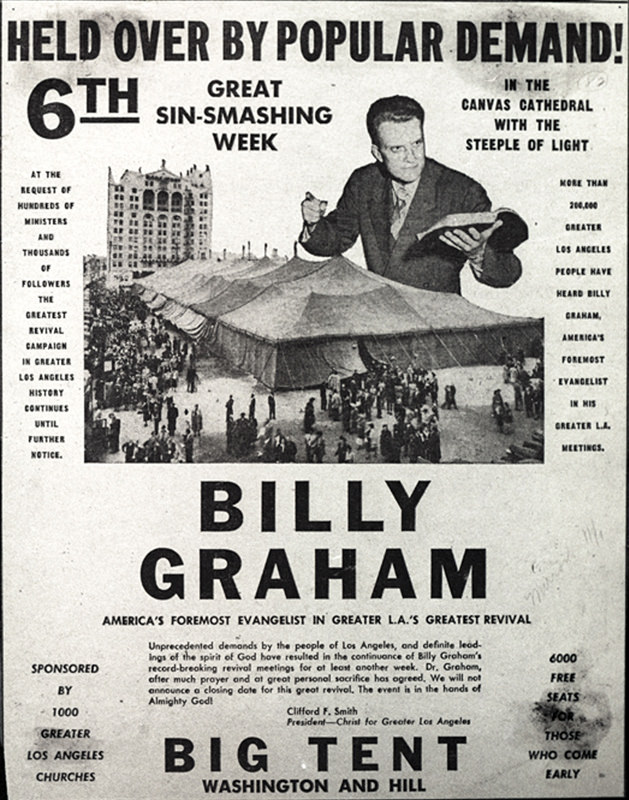

An advertisement for Graham’s 1949 tent revival in Los Angeles.

That Old Time Religion Goes International

Born in 1918, Graham was a man of his moment. Lanky and handsome, self-confident but homey, he was ordained as a Southern Baptist minister and came to prominence after World War II. He stood as a remarkable embodiment of postwar American evangelicalism’s increasing cultural confidence.

He began his public career with a modest tent revival in Los Angeles in 1949 of the sort that has defined American revivalism since the early 19th century. There he attracted the attention of influential newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, who told his reporters to “puff Graham.” Graham’s “crusades” quickly outgrew the revival tent. Eventually these events would attract hundreds of thousands, include musical performances, and require Jumbotrons.

A recreation inside the Billy Graham Library of his 1949 tent revival in Los Angeles.

The timing is important. In 1949, mainline liberal Protestantism was on the cusp of decline. Those churches would lose both membership and cultural influence.

Graham arrived on the scene to fill a growing void. He was determined to bring an insurgent theological conservatism out of the South and into the mainstream of American life. He, along with a cohort of younger evangelicals, wanted to overcome the “backwoods” reputation that had tarred previous generations of fundamentalists.

Graham and other “neo-evangelicals” founded Christianity Today in 1956 and, over the following decades, strove to reshape American culture by using mass media and engaging with politics. In addition, a broad range of other evangelists in the 1970s took up the model of evangelization that Graham had used to such great effect—the large-scale preaching that moved from city to city.

Graham with President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan at the National Prayer Breakfast in 1981 (left top), with President Gerald Ford in the Oval Office in 1976 (right top), with President Richard Nixon in 1973 (left bottom), and with President Barack Obama in 2010 (right bottom).

By the time of his death, the Baptist preacher from North Carolina had met with every president from Harry Truman to Donald Trump.

But as soon as the early 1970s, Graham realized that the center of gravity in global Christianity was moving inexorably to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. At the Lausanne Congress for World Evangelization in 1974, a gathering of 2,700 evangelical leaders from around the world, Graham gave the opening speech where he cheered the visibility and energy of “younger churches.” And when someone later asked him who would be the “next Billy Graham,” he gestured to the international crowd and said, “They will.”

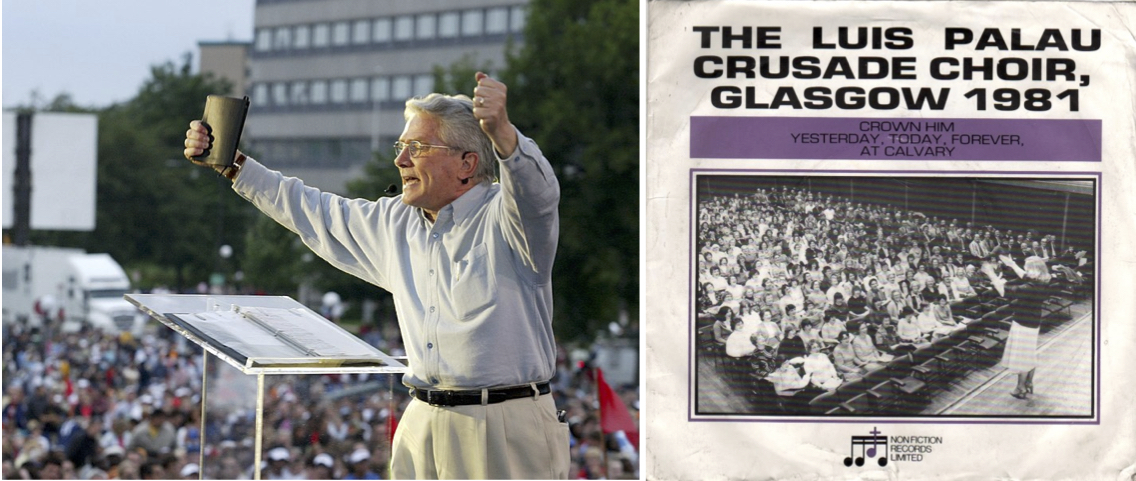

Indeed, one of the most successful of Graham’s close associates was an Argentinian named Luis Palau, who first heard Graham on the radio in 1952. Palau met Graham in the late 1950s and served as the Spanish language interpreter for Graham’s Fresno, CA crusade in 1962.

Luis Palau preaching in 2004 (left). The album cover for the Luis Palau Crusade Choir in Glasgow in 1981 (right).

In his preaching from the 1970s and 1980s, Palau adopted a good bit of Graham’s style, with broad hand gestures and a kind of infectious enthusiasm. It’s not surprising that journalists often referred to Palau as the “Latin American Billy Graham.”

Palau modeled much of his career on Graham’s and organized large crusades in cities in Latin America and Europe. Speaking in either Spanish or English, he attracted large crowds in the 1970s and 1980s, speaking in Nicaragua, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, as well as across Europe. Like Graham, Palau was handsome with an engaging sense of humor, referring to sports or music in ways that make him seem like a pastor one might like to invite for dinner.

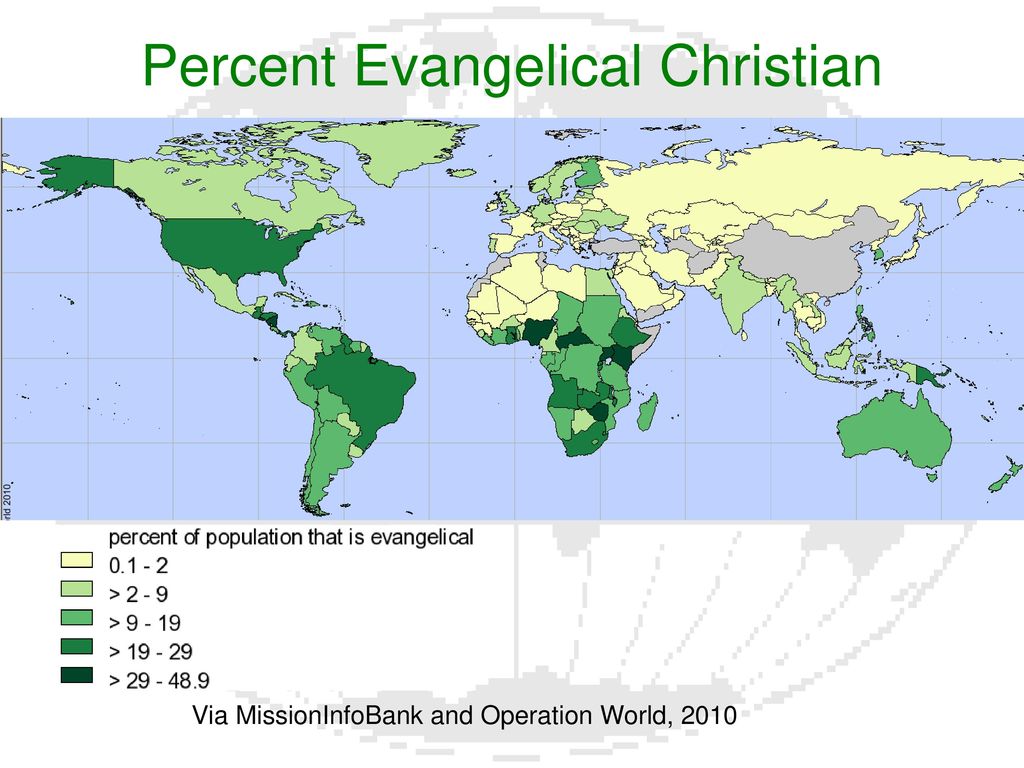

A 2010 map showing the percent of the population that is evangelical.

His story is one that highlights what Graham well understood: the future of evangelicalism was to be in the global South. Today, more than 50 percent of the world’s Christians live outside the United States or Europe and the numbers are even higher for evangelical Protestants. The largest congregations in the world are not in Houston or Atlanta, but in Lagos and Seoul.

The Medium Shapes the Message

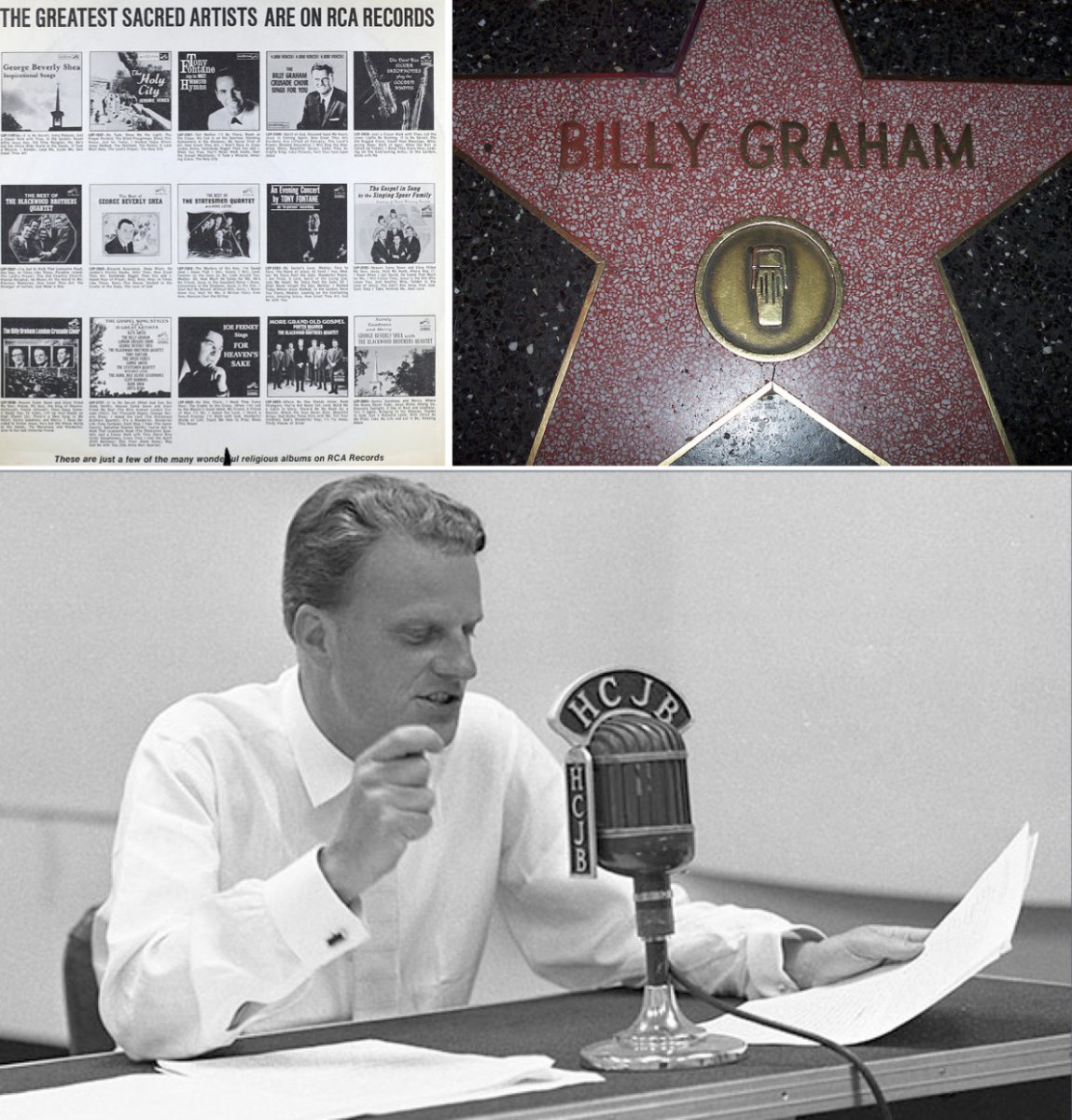

Although he is known for his crusades, approximately 20 million people a week in the 1950s heard Graham’s extraordinarily popular radio show, Hour of Decision.

Radio had been a hallmark of evangelical ministries from the earliest days of the technology. For example, the Pentecostal evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson became the first woman to preach over the radio in 1922. But Graham and his team built on that legacy, broadened it, and institutionalized it. From early on in Graham’s ministry, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association produced television specials and broadcasts of a number of his crusades, as well as the weekly radio show (which ran until 2016).

An advertisement for sacred artists on RCA records, including Graham (left). A star for Graham on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (right). Graham recording a 1962 episode of The Hour of Decision in Ecuador (bottom).

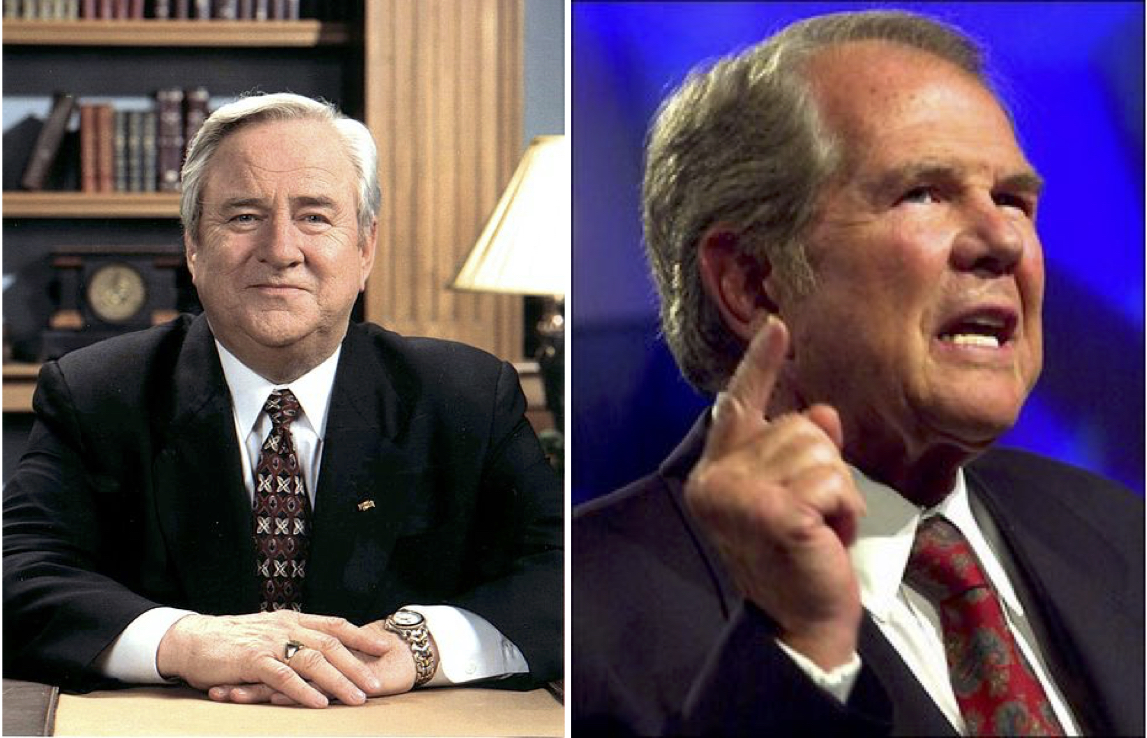

Still, Graham never joined the phalanx of televangelists who, starting in the 1980s, made television their primary medium of outreach. The televangelist generation, including Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, took Graham’s use of media one step further than he did, making TV preaching into its own genre.

To succeed in the televangelist universe, it was not enough just to film your sermon for broadcast. Instead, televangelists built the show around the camera and included the television audience as participants. Whether televangelists sat in a studio interviewing guests on a couch, or simply preached in front of the camera, they did so with an active sense of the importance of the audience. Production values mattered.

Jerry Falwell (left) and Pat Robertson (right).

For many, politics mattered too. Televangelism was a hallmark of the rising Religious Right of the 1970s. Not all of the preachers of that era were part of the movement. A number of the most popular TV preachers—Oral Roberts, Robert Schuller, Rex Humbard, and Jimmy Swaggart—rarely addressed politics directly.

Jerry Falwell, however, did not shy away from politics and often talked about political minutiae with the enthusiasm of a conspiracy-minded amateur historian. His Old Time Gospel Hour had an audience of 1.4 million each week. Just as significantly, Falwell founded the Moral Majority in 1979 and through it rallied Christian conservatives to Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party.

Pat Robertson’s news-and-conversation show, The 700 Club, has been on the air since 1966, starting out on a handful of stations on the nascent Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN). His audience swelled in the late 1970s and by 1985, it aired on 190 broadcast stations in addition to the CBN cable network; 27 million viewers watched the show at least once a month.

A number of evangelists followed in this mold and television distribution became important both nationally and internationally.

The rise of Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) in the late 1970s provided a home for an array of Pentecostal-friendly shows that today are shown on 18,000 affiliates worldwide. Showcasing prosperity and healing ministries like that of Joel Osteen, Joyce Meyer, and Benny Hinn, TBN is a friendly venue for female teachers and preachers, people from the global South, and a racially diverse group of American ministers.

The headquarters for the Trinity Broadcasting Network in Costa Mesa, CA.

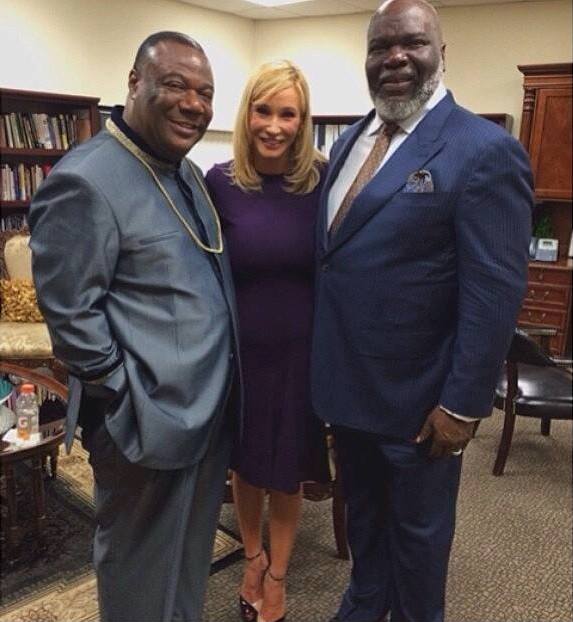

One of the great successes of television ministry—a man who at one point had sermons airing on both TBN and Black Entertainment Television—is pastor T.D. Jakes, of the Potters House in Dallas. Jakes began as a small-town pastor in West Virginia, but in the mid-1990s he moved his ministry to Texas and with his wife founded The Potters House, which soon became a fast-growing megachurch. By the early 2000s, 23,000 people were attending each week. His Neo-Pentecostal style—charismatic, therapeutic, and deeply rooted in the African American church—appealed to a racially diverse audience who longed for a preacher who could combine old time gospel preaching with Oprah-style attention to modern challenges.

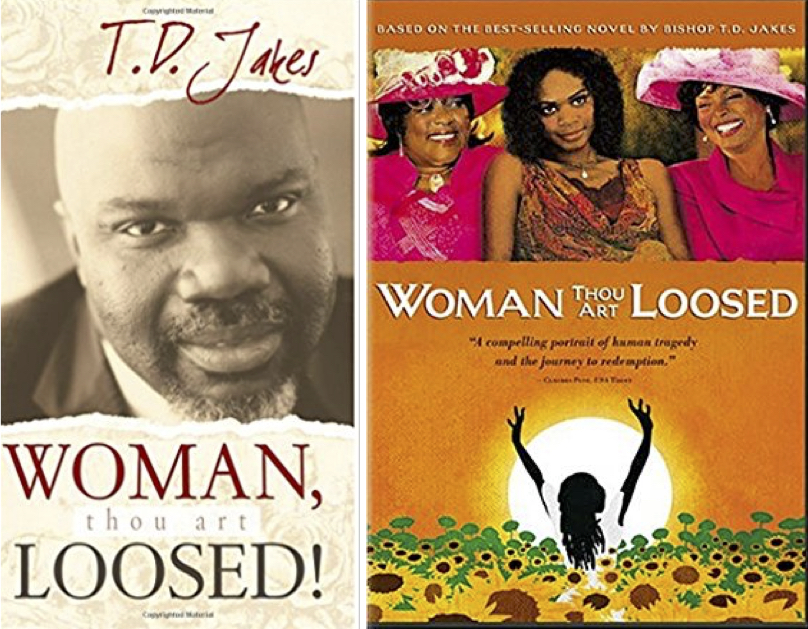

Jakes is very different minister than Graham was. His style is more aligned with the black tradition that highlights syncopated speech and strongly expressed emotion. And, as far as I know, Graham never broke out into song, but Jakes has been known to. (He’s been nominated for a Grammy in the Gospel category.) Jakes became a national figure in 1992 with his performance at a regional meeting of the AZUSA Fellowship.

T.D. Jakes’s 1993 self-help book, Woman, Thou Art Loosed! (left) and the poster for the 2004 film based on Jakes’s book (right).

The September 2001 issue of Time magazine.

Jakes’ products, which include a number of other books and CDs and a dieting book, have made him rich. He and his wife Serita have a multi-million-dollar house in a Dallas suburb. The Bishop dresses immaculately and flies to many of his presentations on chartered planes.

This works well with his theology because Jakes believes in the value of God’s overt blessings. For this, he has been roundly criticized, particularly by African American pastors and theologians who would like to see less focus on personal wealth and more on social justice.

In September 2001, Time magazine put Jakes on its cover, asking “Is this the next Billy Graham?” The answer was, in large part, “no,” because no one could represent “America” in the 21stcentury in the way Graham had claimed to do in the 20th. In a country more self-conscious of its religious and racial diversity, no one person would be likely to hold that kind of iconic status.

But Jakes was, nonetheless, praised by Timeas one of the nation’s best preachers and four years later was included in its list of the 25 most influential evangelicals in America. As a master of multimedia, Jakes had crossed the racial divide in American Christianity, making himself an icon of a new era.

Tweeting her Way to “the Next Billy Graham”

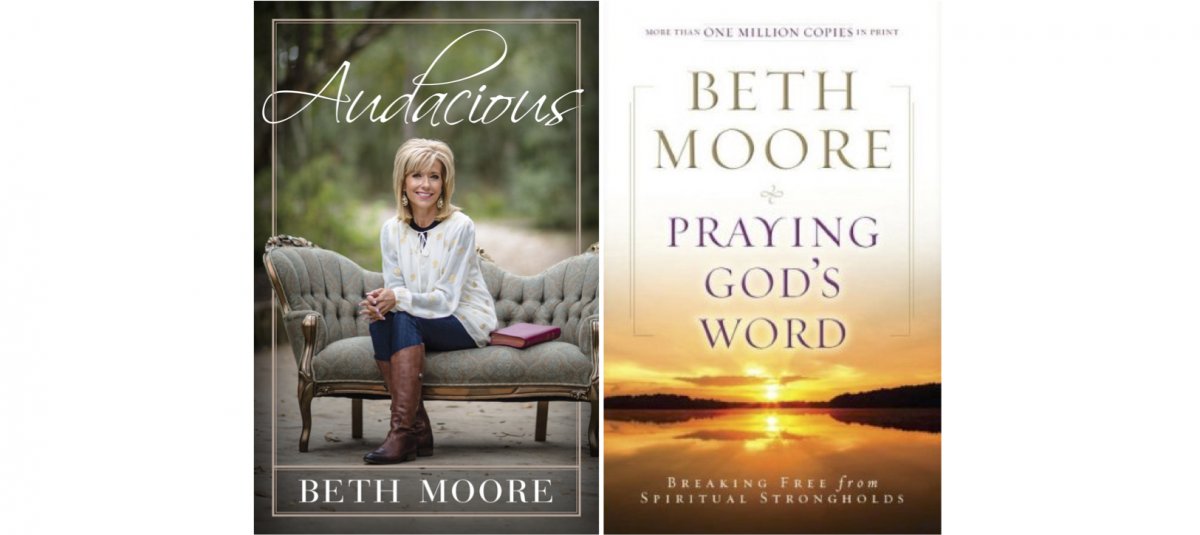

Beth Moore stands on the stage, wearing one of her signature colorful tunics, in front of thousands of women. She’s teaching from the Book of Mark, but now, a little over halfway through her message, she has hit her theme: “Jesus, Because Life is Complicated.”

She talks about her own “complications” and she lists one in particular—aging. As she tells a funny story about wanting her body parts to operate in harmony, she also insists that life gets better as you get older. After all, she says, at a certain point you “no longer feel like you have to meet your husband at the front door in your bathing suit”—a quick, insider reference to the conservative marriage manuals that tell women their job is to always be alluring. She has her audience laughing, tearing up, and clapping, much like they would listening to any great preacher.

Beth Moore’s 2015 book, Audacious (left) and her 2009 best selling book, Praying God’s Word: Breaking Free from Spiritual Strongholds (right).

In 2010, Christianity Today called Moore “the most popular Bible teacher in America.” But she is a Southern Baptist and thus part of a denomination that does not support women as church pastors and whose leaders often argue that women should not “teach” or “have authority” over men. (They are drawing from specific statements by Paul in 1 Timothy 2 and 1 Corinthians 14.)

What happens when your tradition does not allow you to preach, but you believe you have a message? You teach. And you write books. And you Tweet.

Moore is thus a Bible teacher who markets her conference presentations, books, and internet sites as resources for women. And, in one of those ironic twists that mark the history of Christianity in the United States, that limitation has shaped her ministry and helped make her famous.

Moore’s dozens of books are often bestsellers and her Bible study resources circulate well beyond Southern Baptist circles, as people enjoy her humor and her outsized emotiveness. No surprise then that one guest blogger at Christianity Today made the inevitable comparison, promising to explain “why the Bible teacher with the big Texan hair may just be our female Billy Graham.”

Like other teachers who focus on women, Moore has her own organization, Living Proof Ministries, with its blog and numerous archived lessons. And she is active on Twitter, where she has almost a million followers. Moore is not alone: social media is a hothouse of evangelical conversation and Twitter in particular includes people from around the world swapping Bible verses, commenting on issues, and debating issues.

Paula White in 2011 (left). The logo for the Gospel Coalition, a network of evangelical churches founded in 2005 to assist present and future Christian leaders (middle). Darlene Zschech on a 2009 tour of India (right).

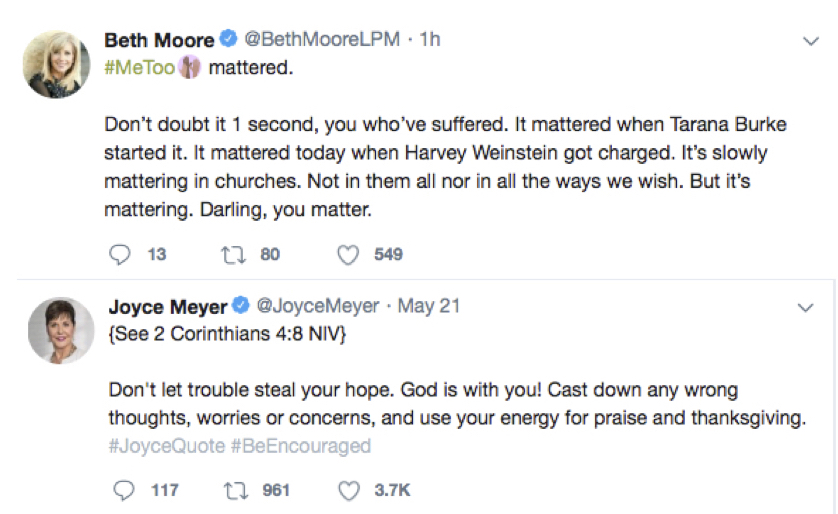

Indeed, conservative evangelical women like Moore, President Trump’s advisor Paula White, Trillia Newbell of The Gospel Coalition, Darlene Zschech of Hillsong church in Australia, and author and evangelist Joyce Meyer have massive followings. (Meyer has a stunning 6 million followers.) Where preaching is not allowed, Tweeting seems to have entered.

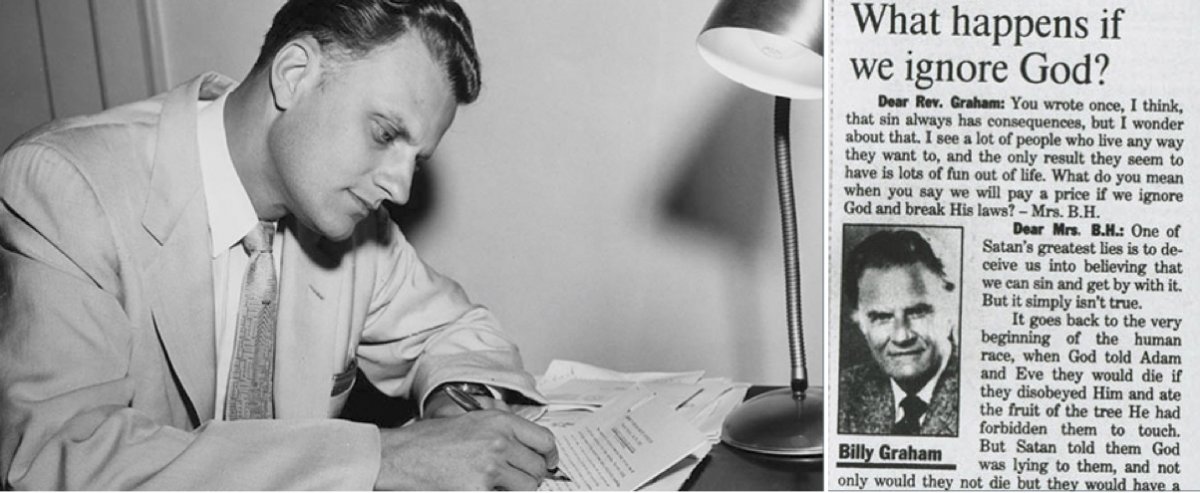

The fast-paced and interactive Twitterverse might seem worlds away from Graham’s ministry of one man on a stage before hundreds of thousands, but it is not—not entirely. Graham also interacted with his followers, in part through his wildly popular advice column, “My Answer,” that ran for 65 years in newspaper syndication. In it, he answered questions about everything from whether Christians could believe in evolution (he originally said yes, they could) to how to handle homosexual desire (pray to be cured) to how a woman could convince her husband to see a doctor (ask nicely).

Billy Graham writing his column, “My Answer” (left) and a newspaper clipping of the column (right).

In the last years of his life, the column was answered by staff from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. In fact, Graham may never have written all of it, given his grueling schedule. But his public persona included a weekly engagement with audiences, who asked questions, raised concerns, and got individualized replies. And that is what Twitter can offer with a new intensity, allowing a “non-preacher” like Moore to connect directly and individually with her very large fan base.

“Pastors tell me, Twitter is just made for the Bible,” one consultant told the New York Times several years ago and that seems to be true. The truncated format of a Tweet still allows for a short verse and a bit of commentary, a quick illustration, a provocative recounting. But Twitter has also made it easy for Christian commentators to speak up about events in their moral universe in ways they might not do when speaking in front of a live crowd.

A 2018 Tweet from Beth Moore on the day Harvey Weinstein was arrested on charges of rape and sexual abuse (top). A 2018 Tweet from Joyce Meyer (bottom).

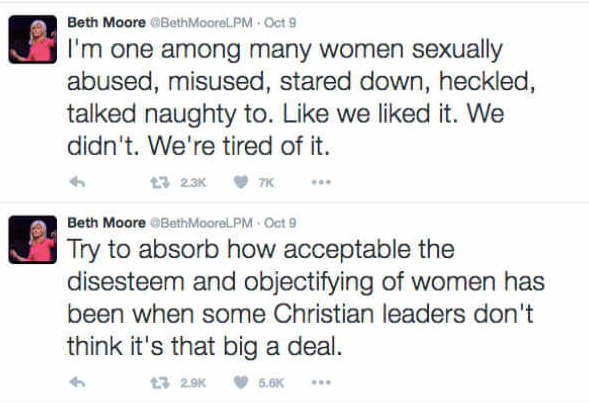

Not surprisingly, the #MeToo movement has traction among evangelicals and others, who often use the hashtag #ChurchToo. As someone who has written about her own difficult life history, Moore herself has been no small player in this conversation. In the fall of 2016, Moore spoke out against revelations about Trump’s sexually predatory attitude toward women with two tweets on October 9 that provoked a firestorm.

Two Tweets from Beth Moore in October 2016 speaking out about sexual abuse and harassment.

Suddenly, the blond Bible teacher in colorful outfits began to seem far more confrontational. And many evangelicals, especially white evangelicals who supported Trump, castigated Moore for becoming “political.” She did not back down.

Then, in the spring of 2018, Moore took a lead role in responding to the controversy over comments by Southwestern Baptist Theological seminary president Paige Patterson, in which he recounted proudly that he had urged a woman to stay with her husband despite physical abuse. Moore joined with more than 3,500 Southern Baptist women who signed a letter saying that the Southern Baptist Convention should not allow “a leader with an unbiblical view of authority, womanhood and sexuality” to remain in his role. On May 22, Patterson was removed from his position as the seminary’s president.

In response to this and other issues, Moore produced a series of tweets and later her own open letter that talked about her experience of sexism in the conservative evangelical circles in which she travels—the experience of going to speak at an event and not being acknowledged in an elevator with a group of men with whom she was about to share a stage, of being sexualized, condescended to, and dismissed. These experiences were not at the same level as those of women who had been abused, Moore said, but the attitudes that engendered both types of behavior were “growing from the same dangerously malignant root.”

Moore created a multimedia empire. But only now has she overtly stepped beyond the confines of “ministry to women” to reach out and demand accountability from men.

After Billy Graham

Palau, Jakes, and Moore have all been compared to Billy Graham, and certainly each of them benefitted from the world that Graham helped make—the rising visibility and respectability of evangelicalism in the 1950s and 1960s, the use of television and new media to reach new audiences in the 1980s and beyond, the development of a personal connection to their audiences, and a willingness to open up new pathways for outreach when old avenues seemed closed.

A statue of Graham in downtown Nashville before it was moved in 2016 to the LiveWay’s Ridgecrest Baptist Conference Center in North Carolina.

But the importance of these great preachers does not come from any ability to replicate the kind of conservative Protestant consensus that Graham embodied. Granted, there are white American male preachers today who also learned from Graham, who might seem more “like” him in identity or in style, but they also inhabit a very different evangelical world than he did: one that is border-crossing, racially diverse yet divided on race, and in upheaval today on matters of gender and sexuality.

Whatever the future of evangelicalism turns out to be, its preachers and teachers are likely to increasingly look like the diverse believers they speak to, connecting to and speaking for the times.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Christianity: The Changing Face of Global Christianity; The People's Pope; Baptized in the Jordan River; Martin Luther and the Reformation; and the Catholic Prohibitions of Copernicanism

Frederick, Marla. Colored Television: American Religion Gone Global. Stanford University Press, 2016.

Griffith, R. Marie. Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Martin, William. A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story. New York: W. Morrow and Co., 1991.

Wacker, Grant. America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014.

Walton, Jonathan L. Watch This! The Ethics and Aesthetics of Black Televangelism. NYU Press, 2009.