Two centuries ago, a young United States stepped militarily into a civil war among Native Americans to bring the war to the end that the Anglo-American leaders deemed correct. Today, the anniversary of the Creek War (or Red Stick War) allows us to reflect on such important ideas as justice, communal violence, and political legitimacy.

Like any civil war, the conflict that broke out among Creek people in 1813-14 stemmed from multiple causes. And like most civil war violence, that of the Creek War manifested long-diverging views among Creek people concerning the direction of their communities. But the civil war was also about justice. Government is rendered illegitimate when people find it unjust, and this occurred in Creek country in 1813—as it has in a handful of Arab nations over the past few years. While certain Creek leaders centralized their authority, many in Creek country questioned the new government’s legitimacy. Differing notions of justice, both within the diverse Creek community and between Anglo-Americans and Creek people, helped fracture the Native polity and frame a legacy of military, economic, and territorial conquest that forever shaped North America.

In broad terms, the Creek Civil War was a clash between those building a capitalist nation-state and those fighting against it. William McIntosh, a headman of the prominent Creek settlement of Coweta in modern-day Georgia, personified the merger of traditional and modern society. McIntosh thought the future of the Creek people was tied to the development of the United States. He drew his considerable wealth from connections to the Atlantic-based market economy through his father, a Scots trader, while his native leadership derived from Creek family connections through his mother’s clan. In learning to write English, codifying Creek law, building private plantations with African slave labor, and centralizing Creek leadership on a national council, McIntosh and others sought to maintain Creek autonomy in the face of aggressive U.S. expansion.

In this 1805 painting, the artist imagines American planter and Indian agent, Benjamin Hawkins, teaching Creeks to use a plow on his Georgia plantation.

The U.S. “plan of civilization” promised that if Native nations conformed to the agricultural, political, and gender norms of the emerging U.S., they could retain their land. Creek leaders such as McIntosh, with their options limited, hoped that their cultural and economic adaptations could secure a future for Creek people in the American South.

A Creek man named Little Warrior viewed change differently. Unlike McIntosh, he was impressed by the Shawnee Tecumseh’s demands for militant anti-American action. In early 1813, on his way back to Creek country from living among northern militants, Little Warrior and a few others killed several white settlers.

Arriving home, Little Warrior told the Creek national council that the outbreak of hostilities (now called the War of 1812) afforded Indians everywhere an opportunity to drive back encroaching U.S. settlement and return to older, stronger Native values. He implied that white and Indian societies were incongruent and that Creek leaders who embraced change were building their own fortunes at the expense of the larger Creek, and Indian, community.

William McIntosh, in an oil painting by Charles Bird King.

Here McIntosh and Little Warrior’s paths met. National leaders debated what to do with Little Warrior and others who carried red sticks—painted the “color of justice” and symbolizing brotherhood with Tecumseh. In April, the Creek council decided to execute Little Warrior, a deed they accomplished under McIntosh’s leadership. “It is true,” McIntosh reported to a U.S. agent, that Little Warrior “punished white people,” but the Creek Nation took his life “to pay, according to law.”

Little Warrior’s execution was one of the sparks that ignited the Creek War. Seminoles and African Americans joined Red Sticks in an alliance of fighters who stood to lose much by Creek centralization and transition to a plantation economy. Nationalist Creek leaders countered by requesting help from the American army. Andrew Jackson led his force into Creek country, ending Red Stick military resistance at the March 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend (and making McIntosh a brigadier general). But the victorious faction of Creeks soon paid a dear price for their alliance. Jackson demanded that the Creek Nation cede 23 million acres, nearly half of their communal land base, a tract larger than the size of modern Portugal. American officials, citing the “unprovoked, inhuman, and sanguinary war, waged by the hostile Creeks,” framed the enormous territorial payment as justice for the violence of the Red Sticks. For their part, according to historian Claudio Saunt, Creek leaders who had opposed the Red Sticks were more concerned that the treaty failed to remunerate their property destroyed by war than the loss of Creek land base. When the U.S. entered the Creek Civil War, all Creek people lost.

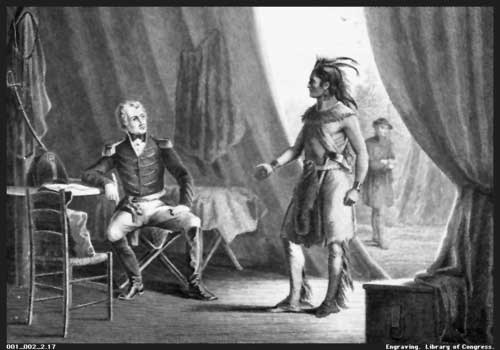

Andrew Jackson accepting the Red Stick surrender after the Battle of Horseshoe Bend).

Two hundred years later, Creek people, now citizens of multiple nations, have reason to reflect on justice as they remember the struggles of their civil war and American military intervention. Memorial of the Creek War among Creek peoples has been dampened by an argument over Hickory Ground. When the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, those now based in Alabama, decided in the summer of 2012 to significantly expand their gaming operations at Hickory Ground (ironically the place where McIntosh attacked Little Warrior) the Muscogee Creek Nation, those now based in Oklahoma, attacked the excavation of Creek burials as a desecration of sacred space. The fact that the former has sued the latter (and the latter’s statements since) illustrates the depth of feeling for Creek heritage and the legacy of a removal that again split the nation.

Once again, the U.S. government will mediate the dispute, albeit with instruments more peaceful, and we hope more just, than the hooves and bullets of Jackson’s army. Both Poarch Band and Muscogee Nation (today, two distinct polities) trace their ancestry to the battered Creek nation that emerged from the civil war 200 years ago. However, this time it appears that a U.S. court will decide the Creek argument over the direction of their communities.