Every election year is a good time to remind each other that you do not discuss religion, sex, or politics in polite company. Sex to one side, in America’s Religious Wars, Kathleen M. Sands reminds us that talking about religion has always been a vehicle for talking about politics in the United States.

From the very beginning, Americans have viewed many of their acrimonious social relations through the lens of religion or through its opposite, secularism. Conflict between these one-or-the-other conceptions is woven into the nation’s history.

Sands explores this by examining what she terms “religion-talk.” This discourse folds wider social issues and ethics into a fabric of spiritual belief and divine judgement. Arguing about religion, therefore, is often a means of arguing about the meanings of other elements of our social and political lives, such as equality, freedom, limited government, community, dignity, and the distribution of resources.

Religion-talk is a power struggle. Religion-talk showcases deep disagreement and the intellectual gaps presented by religious strife. Unfortunately, as Sands sees it, religion-talk does not provide a common language with which to agree on visions, solutions, and resolutions, for the future of national life.

Through the three sections of her book, Sands presents the history of ideas that have shaped American religious strife. In Part I, Sands plays on construction metaphors to describe what she sees as the central fault line in our religious debates: foundations vs. walls.

George Washington believed that religion needed to be the foundation of the American polity, while Jefferson insisted that the Constitution built a “wall of separation” between religion and the state. Each side used intellectually inconsistent religion-talk to sanction what they already believed was the right way of viewing political issues, and we’ve been trying to square that circle ever since.

In Part II, Sands demonstrates that the tensions between "walls" and "foundations" lay at the root of the hostilities—and sometimes opens violence—directed by American Protestants against Mormons, Catholics, and Native Americans.

These conflicts were not simply hold-overs from an earlier time when religious differences were at the heart of so much violence. Sands explains that the theologies of Mormons, Catholics, and Native Americans were seen as so threatening to the Protestant majority that they had to be walled off in order to preserve a Protestant notion of the common good.

The question is not “which religion should be our foundation, or whether religion has any place in our foundation,” but what are the big-picture norms, commitments, and sensibilities that unite American social and political life?

In this section, she explores these questions with a chapter on race and the controversies over creationism, and another on the present strife between religious and secular society as seen through the lens of same-sex marriage.

In the last chapters, Sands focuses more directly on recent conflicts between science and religion and the way arguments on both sides remain rooted in the walls and foundation paradox. Sands argues that for creationists or those opposed to same-sex marriages religion is deployed in order to preserve that sense of Protestant common good, nevermind that those people now also include Catholics.

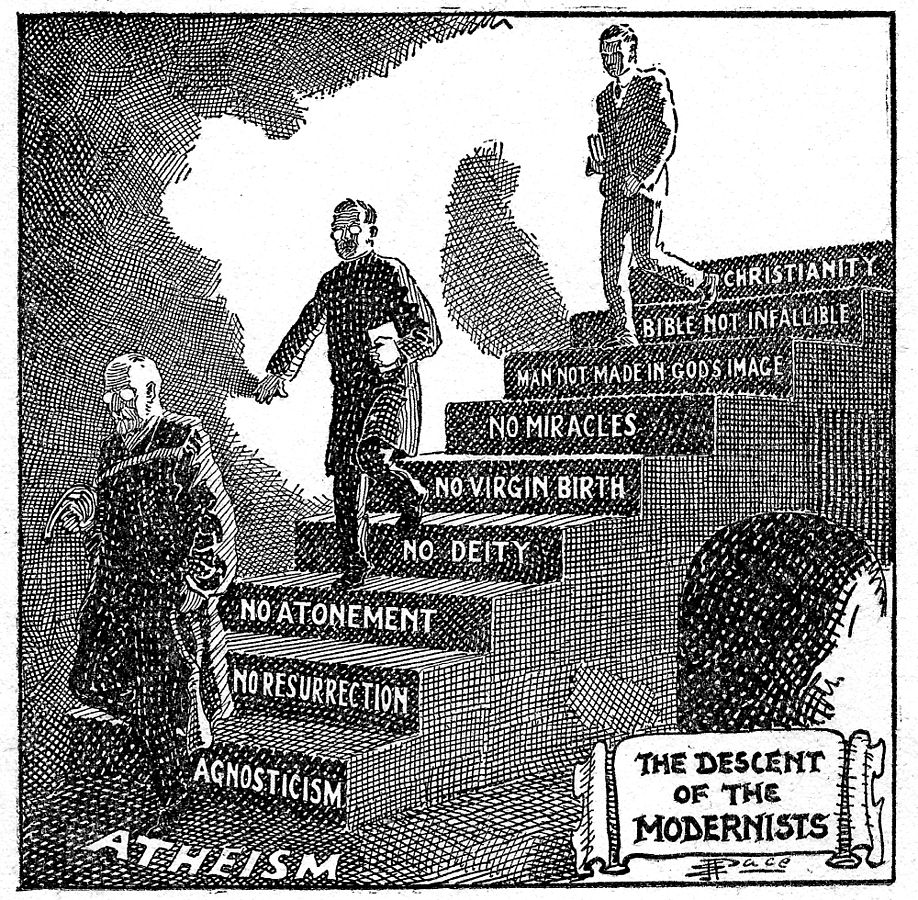

Instructive is the story presented in the closing pages of Chapter 5. Sands introduces a twenty-first century school board member in Dover, Pennsylvania, site of a 2005 federal court case involving neo-creationism, who grinned while he stood in front of a “Descent of Man” mural while it burned. Fighting vehemently against the forces of the New Atheism, a term coined in 2006 to label writers like Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, this school official was the rearguard of a decades-long culture war made up of anti-modernists against religious modernists.

This ostensibly religious controversy is meant to encapsulate the entirety of Sands’s history though it is specifically framed in the context of debates over neo-creationism in the classroom.

Sands emphasizes this conflict to underscore a profound point. “What ails knowledge in the United States cannot be reduced to religion, nor can the remedy be reduced to science. What ails us is being human...what heals is knowledge of ourselves and our relations.” Americans, in her view, should reject religion-talk and its associated baggage.

Ultimately, Sands wants Americans to learn how to disagree more productively in public debates because we cannot keep swinging between two opposite poles: religious belief or faith in secularism. While the lessons of Sands’s book are many, there is little space devoted to helping the reader conceptualize the important interplay between religious doctrine, secular law, and the American court system.

The ideas Sands lays out are key to the long history of American religious conflict, but only after a close read and reflection will readers be able to piece together the narrative’s many moving parts.