In my November 2011, Origins article, Energy Policy and the Long Transition in America, I concluded that “environmental politics have made a difference in energy policy-making since the 1970s, shaping the long transition in new ways.”

|

| Windpower, like the windfarm above, has the potential to provide all of the electricity used in the state of Idaho. |

I also predicted that, “For the foreseeable future, however, the economics of alternative sources, sustainable fuels, and clean energy will hinge on the price of coal and petroleum, and given the immense supplies of both, the interest group influences, and ideologically based politics, the long transition will likely continue for some time.”

How have those conclusions played out over the last four years?

The transition from carbon-based to cleaner alternative fuels has been speeding up over the last four years. The reasons for that are many, complex, and subject to change in the near and far future. In addition, as this is written in early 2016, the price of oil has plummeted to its lowest level in seven years. Americans are paying on average just above $2.00 per gallon of gas. Many observers do not see a change for six months or more.

Why is that so? And what impact will these low oil prices have on the long transition?

Why has the price of oil gone so low?

The petroleum industry has survived numerous booms-and-busts since the middle nineteenth century. The only period when this pattern did not hold was from the mid-1930s to the 1960s when the United States was the major producer of oil in the world.

Instead of market forces shaping the price of oil, American public policies matched supply to demand creating more price and production stability. When producers outside the U.S. increased oil production, the U.S. reduced its own output to keep the price relatively stable. When other nations needed more supply (for example, Western Europe during the Suez Crisis in the middle 1950s), Americans produced more oil.

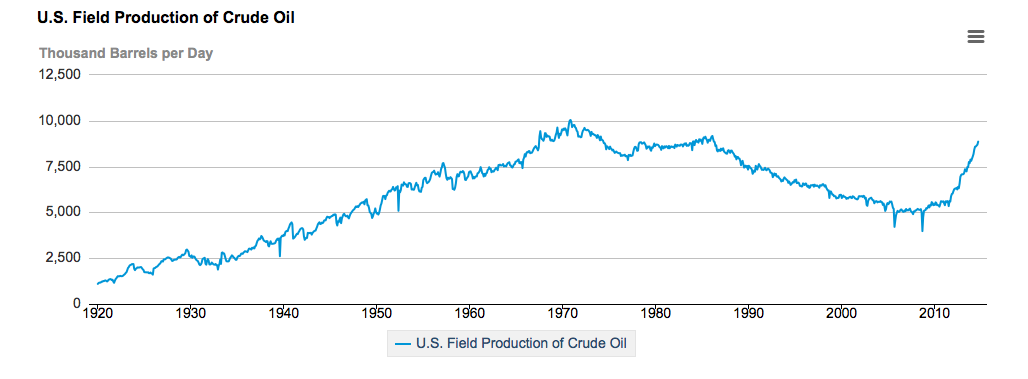

|

| This graph shows the fluctuations in United States oil production over the last century. |

With the rise of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) in the 1960s and 1970s, however, the U.S. lost its ability to influence the supply and therefore the price of oil. The U.S. Congress dismantled the political mechanism controlling the supply and prohibited the export of American oil.

From the 1970s to the 2000s, OPEC managed a general rise in the price of oil, although fluctuations did occur. Using yearly averages in inflation-adjusted dollars, the 1970 price of $20.63 per barrel increased to $107.36 in 1980; fell to a low of $29.73 in 1988; and, fluctuated in the $20-$30+ range between 1988 and 2004. In 2005, the price began to rise; during 2008, it increased to over $145 per barrel, but then fell to $32 (because of the Great Recession).

Instead of Americans controlling the price of oil, supply and demand, economic expansions and recessions, and some OPEC pressure determined the price of oil.

Following the height of the Great Recession in 2008, and through a combination of possible trader manipulation, political uncertainties in the Middle East and elsewhere, and national economies reacting to worldwide recession, American oil prices fluctuated in the $60 to $90+ barrel range. Between 2010 and 2014, the world-wide price of oil remained around $110.

Beginning in June 2014, however, the price of oil began to fall. By the autumn of 2015, a few observers thought the price might go below $30.

|

| A horizontal directional drill in operation. |

What explains this most recent drop in the price of oil? And is it any different than earlier decreases?

Between 2008 and 2015, high prices (demand) encouraged American oil drillers to find more oil (supply). Continuing technological breakthroughs (fracking and horizontal drilling) enabled them to do just that and more efficiently. Oil producers restarted old fields and developed new ones in Texas and North Dakota, particularly.

While other nations pushed back against using fracking, U.S. production became relevant again.

So American drillers drilled and drilled. With increased supply, and falling demand given the less than robust recovery from the Great Recession and anemic economic growth in emerging economies (particularly in China), the price of oil began to drop by 2014.

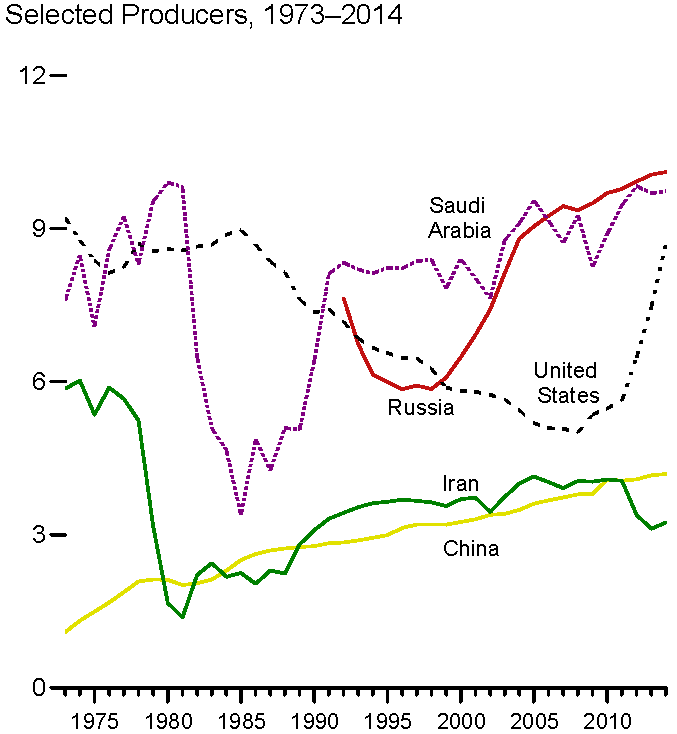

During past cycles, falling oil demand pressured OPEC to reduce production in order to keep prices up. About 80 percent of the Saudi national budget is paid for with oil receipts, and as the largest producer, the Saudis often led the way for the rest of OPEC.

This time, though, Saudi Arabia decided to expand its output. Saudis believe that they can outlast the Americans because their costs of production are so much lower. They want to maintain market share. And the increased American production challenged that.

In addition, geopolitical forces contributed to the Saudis decision to maintain supply. The Middle Eastern kingdom competed with on-going Russian and prospective Iranian oil production.

|

|

|

(Left) Russian oil rig in the Pechora Sea. (Right) This graph demonstrates the continued competition between oil-producing nations. |

So, late in 2015, the world market was awash in oil. Basic oil supply and demand economics, along with geopolitical conflicts, were behind the glut.

The consequences of the low price of oil have been several in the U.S. Drilling rigs have been moth-balled; production has been falling. Employment numbers and average wages in the petroleum industry are dropping. Stock prices for petroleum firms have sunk. There is some pressure on banks holding notes for drilling companies.

In short, the consequences match every other “bust” in the history of the American petroleum industry.

Overseas the price decline has had negative effects as well. Emerging markets based on natural resource extraction face weakened currencies and slow-growth or negative-growth economies. At the end of 2015, Saudi Arabia reported an almost $1 billion budget deficit. The Russian currency was under pressure, making the economic problems there more acute.

What impact will the low price of oil have on the long transition?

Basic economics suggests that continued low oil prices will delay adoption of alternative energy sources, which are generally higher-priced, and thus stall the transition to a green energy economy. Indeed, the International Energy Agency predicts that is what will happen.

The problem with basic, theoretical economics is that it often ignores the real world, particularly changing political dynamics but also sometimes economic realities.

Let’s remove one false idea right now: Public subsidies support both carbon-based and alternative energy industries. Subsidies for carbon-based fuels have been dropping, according to the International Energy Agency, in part as some nations attempt to respond to climate change, but they still total world-wide almost one-half trillion dollars per year.

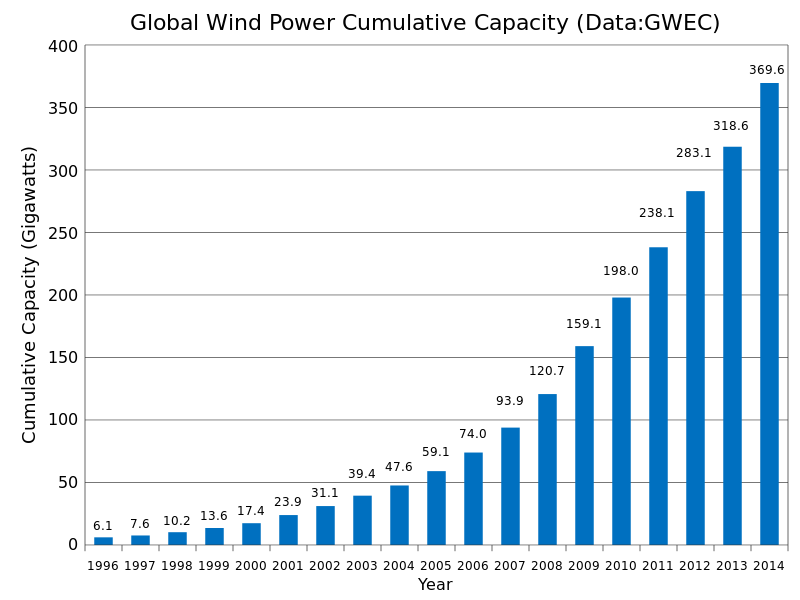

As noted in the 2011 article, political actions, including subsidies, in the U.S., Europe, China, and elsewhere have combined with technological changes and economic forces to support the transition to a cleaner energy future.

|

| Wind power has continued to grow in capacity over the past two decades, despite the lowered oil prices. |

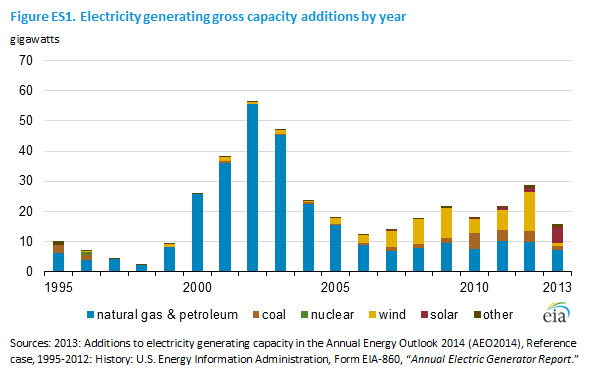

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced new plans to increase the amount of clean power in the nation by reducing the amount of carbon-based emissions in the air. While some states are battling the new standards, others (e.g., Kentucky, Iowa, and Nevada) have determined that they can meet the new standards easily.

Meanwhile, many older coal plants have been retired, many replaced with natural gas, a much cleaner fuel than coal or oil.

In fact, in April 2015 natural gas overtook coal as the number one fuel producing electricity in the U.S. Two reasons help explain why natural gas overtook coal: the falling price of natural gas and enforcement of environmental laws.

In addition to institutional efforts, American individuals have made investments to speed up the transition.

Billionaire Michael R. Bloomberg (the former mayor of New York City) continues to donate tens of millions of dollars to go “Beyond Coal” (see earlier article). Most recently he has funded legal efforts to battle states attorneys general who are trying to block the EPA’s efforts to reduce power plant emissions.

|

| Although basic economics suggests that continued low oil prices will delay adoption of alternative energy sources, this has not been the case as this graph shows. |

Another multi-billionaire, Bill Gates, has attracted 30 other wealthy individuals to join him in the Breakthrough Energy Coalition. They believe that energy policy should be focused on climate change and that requires massive expenditures in technological innovation. Others are not so sure this is the best approach, given the long-term aspects of such research.

Unexpectedly, the most recent budget deal in Congress held a surprise for the long transition: In exchange for removing the ban against oil exports established in the 1970s, politicians supporting alternative energy sources won a five year extension of subsidies for solar and wind power.

The current subsidy program has sustained immense growth in both technologies, even though they represent much smaller contributions than natural gas and coal. The additional time could be transformative. Or not: Some believe that solar is competitive now with other energy sources and that to continue subsidies will slow innovation.

Part of the transition involves businesses thinking more holistically about how they use energy. More corporations are joining the sustainability movement. By focusing on conservation and adoption of renewable energy sources, businesses are discovering that “going green” is good business. Since 2005 Forbes has been listing the top 100 firms based on sustainability.

American environmentalists insist that it is America’s leadership in the world that has promoted a faster transition from carbon-based energy sources to a green economy. To be sure, American leadership was evident in the recent two-week United Nations Conference on Climate Change, held in Paris in early December 2015.

The fact remains, though, that many other nations – who have had less of an impact on the climate than the U.S. – have been active earlier and more vigorously than the U.S. Others are beginning to react out of necessity.

Some nations, of course, have taken advantage of the “free rider” effect in cleaning up the environment by refusing to spend money that would bring no short-term gain to their economies.

Perhaps the key difference from four years ago is that solar power has emerged more quickly than most believed possible. Actions in three nations – Germany, China, and the U.S. – made this so.

|

|

|

Significantly, solar panels challenge the old centralized-system approach of delivering electricity. Constructing centralized distribution systems in poor areas is not going to happen because they are too expensive. But the decentralized use of solar panels might be the answer to electrifying developing areas of the world without increasing the harmful effects of carbon-based fuels.

|

| Liquefied petroleum gas containers in India. |

In addition, India has been touting the use of LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) for some time now. LPG is much cleaner, and thus healthier, than charcoal or coal for cooking and heating purposes.

Not all of the news is good. Despite progress in using solar and LPG, China and India continue to use increasing amounts of coal to sustain their emerging economies. China is taking advantage of low oil prices to stockpile more petroleum. Germany has some of the highest energy prices in the world, and is still too reliant on coal.

Many other examples of progress and lack of progress towards a greener energy mix could be cited. Readers are encouraged to find out what is going on in Mexico (where a large wind farm in Baja is supplying electricity to Southern California) or Australia (a nation not known for its climate change policies is nonetheless increasing its production of natural gas) or a hundred other nations around the world.

In conclusion, during the last four years, environmental politics have continued to shape the long transition from carbon-based to greener alternative energy sources. The low price of oil since 2014 has so far had no effect in stemming the progress. And there are indications that the transition will continue to speed up.