Travelers to Uzbekistan almost all begin their journey at the large, recently remodeled airport in Tashkent, the nation’s capital and a modern city of well over two million people. But to head to the architecturally magnificent and richly historic town of Khiva (formerly known as Khorezm), one leaves behind the tree-lined streets and canals, the cinemas and supermarkets, and the subway – refreshingly cool even during the heat of summer – and hops aboard the train for the long ride to the north.

Minaret Islam Khoja in Khiva (Khorezm). (Photo by author)

The iconic Syr Darya River stretches out alongside the fast-moving rail cars. The river is still bloated with water that days earlier had been snow, melting from the mountains that surround the Ferghana Valley in the southeastern corner of the country. Horses pasture off in the distance, and the train rushes through a never-ending sea of cotton fields.

Before long the train reaches Tamerlane’s historic capital of Samarkand, and those passengers eager to explore the medieval monuments gather their bags and exit the train. Back on board, the hours tick away, the landscape changes from green to brown, and Tashkent disappears into a distant memory.

The desert seems endless, but it is not. Eventually, and gradually, patches of rugged brush appear, and then trees, and then more cotton fields. The train has passed through the Kyzyl Kum (Red Sand) Desert and made its way to the even more iconic Amu Darya River, which earlier on forms the political border with Afghanistan.

Irrigation canals draw so much water from both rivers that the Aral Sea, historically one of the largest inland bodies of water in the world, has all but disappeared. This is the modern history of Khorezm, the fertile region that unfolds along the Amu Darya as it approached the Aral Sea. This represents one of the worst environmental disasters in contemporary history.

The train stops in Urgench, a quiet and comparatively modern city of about 150,000 people. Exiting the train station, taxi drivers are waiting to take travelers the rest of the way on their journey, a short drive of just thirty minutes or so through the searing heat to Khiva, the “museum in the open” that was, from the sixteenth century, the regional capital.

Restaurant menu on the streets of Khiva. (Photo by author)

Khorezm itself claims more than two millennia of recorded history: a precious “jewel” in the middle of the particularly harsh steppe. As the region became populated with Turkic nomadic tribesmen from the early centuries of the Common Era, Khorezm became an important commercial and exchange center between nomadic and sedentary populations.

Archeological evidence indicates that the earliest inhabitants of Khorezm settled in the region sometime around 2000 B.C.E., and local populations had developed large irrigation agriculture by the fourth century B.C.E. Khorezmians were minting their early coins by the second century B.C.E.

A century later the Khorezmian ruling dynasty, known as the Afrighids, had asserted their authority over the region, which they controlled for 1000 years. Gradually, they became more widely known as the Kings of Khorezm, or the Khorezmshahs. The Afrighids retained this title until 995 C.E., when power shifted into the hands of the neighboring Amir of Gurganch, and then to the Ghaznavid who invaded the region from their base in Afghanistan.

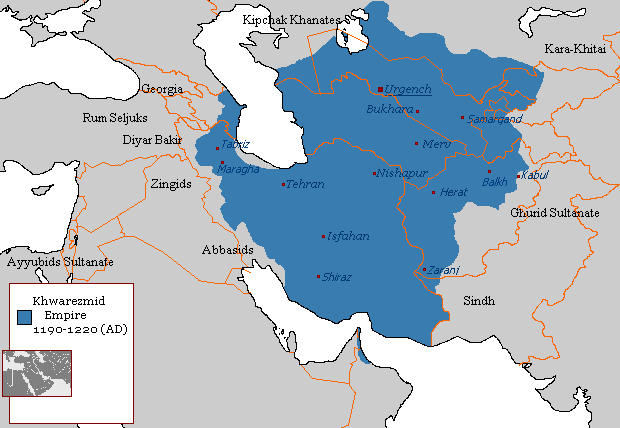

Map of the Khorezmian Empire in 1217 C.E.

During this period Khorezm became more closely linked to the imperial traditions that had become dominant in the wider Islamic world.

Khorezm emerged as a major center of scholarly achievement during the Arab Scientific Revolution that the ‘Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258) promoted. The Khorezmian ruler Ma’mun II (r. 1008–17) established an academy of science in Khiva, which developed into a major center of learning in the medieval Islamic world.

Abu Raihan al-Biruni depicted on a Soviet postage stamp.

Many of the scholars who worked at the institution remain famous today: these include the famous astronomer Abu Raihan al-Biruni, who, five hundred years before Galileo, advanced an astronomical model in which the Earth revolved around the sun; the physician Ibn Sina, known in Europe as Avicenna, whose Canon of Medicine represented the most advanced medical treatise in the world at the time; and of course, the mathematician Muhammad ibn Muso al-Khorezmi, whose text al-Jabr gave rise to the scholarly field of algebra, and whose own name (al-Khorezm) came to be Anglicized in the world “algorithm.”

These scholars not only contributed to knowledge transfer by studying and critiquing the works of the ancient Greek scholars, they also advanced that knowledge.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Khorezmian civilization was demolished by the Mongol conquests. In the decades that followed, recovery came to some places, but Khorezm was reduced to a regional power and was no longer the center of political power and scholarly activity that it had once been.

However, during the second half of the 18th century, Khorezm once again began to emerge as an important political center, but this time with a different name and under a different dynasty. Scholars generally refer to the Khorezmian state of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the Khivan Khanate.

For the last 150 years before the region became incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Khorezm Soviet Socialist Republic in the 1920s, the Uzbek Qongrat tribe took over the leadership of the Khivan Khanate.

The first half of the 19th century was a period of centralization and consolidation for the Khanate of Khiva. Qongrat rulers, starting with Eltuzar khan (r. 1804–6) and Muhammad Rakhimkhan (r. 1806–25) implemented a series of administrative, territorial, and economic reforms in an effort to form a centralized state administration. The reforms effectively brought together the nobility and other elements of social leadership to form a new administrative council. Muhammad Rakhimkhan also developed a new land collection policy in order to unite the various territories of the historical state of Khorezm either by force or by agreement.

The Muhammad Rakhimkhan madrasa, 1871. (Photo by author)

Along with political reforms, Muhammad Rakhimkhan implemented fiscal reforms, established a customs system, and established a mint to create Khivan gold and silver coins. Khivan rulers also worked to improve the ability of caravans to travel safely through their region, thereby improving Khiva’s commercial connections with other regional markets, including Astrakhan, Bukhara and Balkh.

In 1873, after two failed attempts, the Russian military conquered the Khivan Khanate. The Khivan khan made a peace agreement with the Governor General of Kaufman and accepted the status of Russian protectorate. Khiva continued to be a protectorate under the Russian Empire until the Empire itself came to an end in the Bolshevik Revolution and Khorezm became divided between the Soviet Socialist Republics of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan

Today, Khiva is the historic and cultural center of Urgench province of Uzbekistan. Along with Samarkand and Bukhara, Khiva is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage City.

Arabkhan madrasa, 1616. (Photo by author)

Visitors are greeted with comfortable hotels, restaurants and cultural events. And the Ichan Qala (Inner Citadel) is the central part of the historic city, exceptionally well preserved as a living museum with its traditional mud houses, mosque and madrasas, and administrative buildings together with Khivan khans’ winter palace all situated inside the walls of the citadel.

The entrance to Ichan Qala (right). (Photos by author)

The streets of Khiva. (Photo by author)

To enter the old city, one can easily imagine stepping back in time to the nearly forgotten history of nineteenth-century Central Asia.