|

| Pilot whales stranded on Farewell Spit, 2015. |

On 13 February 2015, 198 pilot whales stranded in Golden Bay on the northern coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Hundreds of volunteers were mobilized by New Zealand’s Conservation Agency, racing against time and tides to save the lives of the stranded whales. Despite the efforts of the Department of Conservation and New Zealand’s Project Jonah, 78 whales restranded the following day, and at least 100 died.

Although the exact cause of the stranding remains unknown, the response to the death of the whales may be a unique approach, highlighting the intersection of religion and conservation efforts. The dead whales were given a karakia (a ceremonial prayer) by a local religious leader, and tied to ropes and anchors off the bay, left to decompose within the ecosystem.

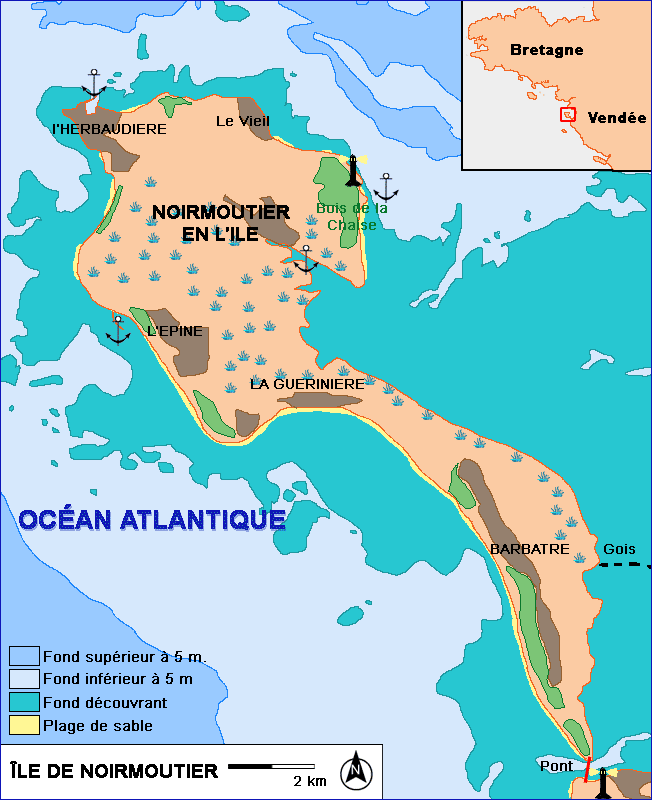

Europeans who lived in the Middle Ages responded to mass stranding events (MSEs) in their own religious ways but their treatment of the beached mammals was very different. In the year 674, St. Philibert founded the monastery of Noirmoutier on an Atlantic island off the coast of France that still bears its name. At some point in the following decade (he died in 684), a group of 237 porpoises was involved in a mass stranding event nearby.

This event is recorded in the 7th-century biography of the saint, the vita Filiberti, or “Life of St. Philibert.” This event most likely occurred in the tidal estuary of the mouth of the Loire and is perhaps the earliest recorded mass stranding event in the Bay of Biscay or even on the Atlantic coast.

The story of the stranding event is short, and can be given in full:

|

| Map of the Ile de Noirmoutier. |

And at another time, when a great famine had begun to constrain the territory of Poitiers, and the man of God [St. Philibert], mindful of the needs of the brothers, lay himself down, praying. And when he rose, a great multitude of the fish that are called marsuppas (harbor porpoises) found themselves in the river. When the sea receded, two hundred and thirty seven of them remained on the dry banks. From that point and for the space of an entire year, the brothers had a huge increase in their comfort, and many monasteries and paupers had food aid.

The medieval actors who encountered and interpreted this stranding understood its causes in multiple ways—some of which resonate with our own scientific understandings and some of which seem more alien to us.

Framed as a miracle story, this account demonstrates the medieval belief that the natural world could be an agent of divine will, supporting the pious who were loved by God.

The aftermath of this medieval event lets us compare modern attitudes towards marine life to pre-modern ones, especially in a shared concern for scarcity and abundance. A deeper awareness of the complexity of past views of nature can help us deal with our own relationship to the fragility and finitude of marine ecosystems.

Patterns of Atlantic MSEs

If the medieval description of a stranding of 237 animals is at all close to the actual number, this would not only be a very early account of an MSE, but it would also be among the largest single MSEs ever recorded in Atlantic or North Sea waters.

For decades, stranding networks across Europe have tracked individual and mass cetacean strandings. In June of 2008, 26 dolphins died in a MSE in Falmouth Bay; before that the largest MSE in English waters had been the 1938 stranding of 15 animals. One of the largest European events in recent years was the stranding of 100 common dolphins at Pleubian on the coast of Brittany in 2002, though only 53 animals died.

(Viral outbreaks—such as the deaths of 877 dolphins in Peru in 2012—have claimed much greater numbers of dolphins, but such events usually take place over hundreds of miles of coastline and differ from the kind of single-event beaching described by the medieval source.)

| These false killer whales were part of an MSE in Flinders Bay, Australia, July of 1986. |

There have been many causes suggested to explain MSEs, ranging from sickness of the animals to unusual climate factors to sonic disruptions. One other commonly suggested cause is that the animals get trapped by changing tides, especially in strong tidal rivers and at sites where beaches, sand bars, and other topographic features might confuse the animals’ navigational abilities. The mouth of the Loire may have presented a “stranding beach” likely to trap passing schools of dolphins.

The French stranding network has kept records of beached mammals and seabirds from the 1970s through today. Their data estimates that in the two decades from 1990-2009, 11-20 stranding events (often of only 1-2 animals) occurred per kilometer of coastline around Noirmoutier.

Thus the large number of stranded porpoises in the vita Filiberti is startling. Yet, when numbers in medieval accounts are exaggerated, it is usually to round numbers (and often has to do with military accounts) or to symbolic numbers, neither of which 237 is. The precision of this number is suggestive of an attempt to realistically portray and record a remembered event of real significance.

Marine Mammal Life in Medieval Times

We know of many medieval accounts of the beachings of individual cetaceans, as well as the active hunting of whales and dolphins. Historian Vicki Szabo has convincingly described that whales and porpoises were in fact deliberately hunted during the Middle Ages, but beachings were still the most common way that medieval communities encountered large marine life.

She also points out that, while we know very little about the population sizes of medieval cetacean communities, it is probable that populations were higher than today, and that “more whales also may have stranded in an age of larger whale populations.”

Yet when we are able to consult medieval sources, it seems strandings were still infrequent and involved small numbers of animals.

Records from 1379-1479 show only 22 stranded porpoises, and a manor belonging to Battle Abbey near the English Channel only reported 4 stranded porpoises between 1482 and1535. Even taking into account a larger medieval porpoise population, all evidence suggests that the event in 674 would have been a strikingly large and significant one.

|

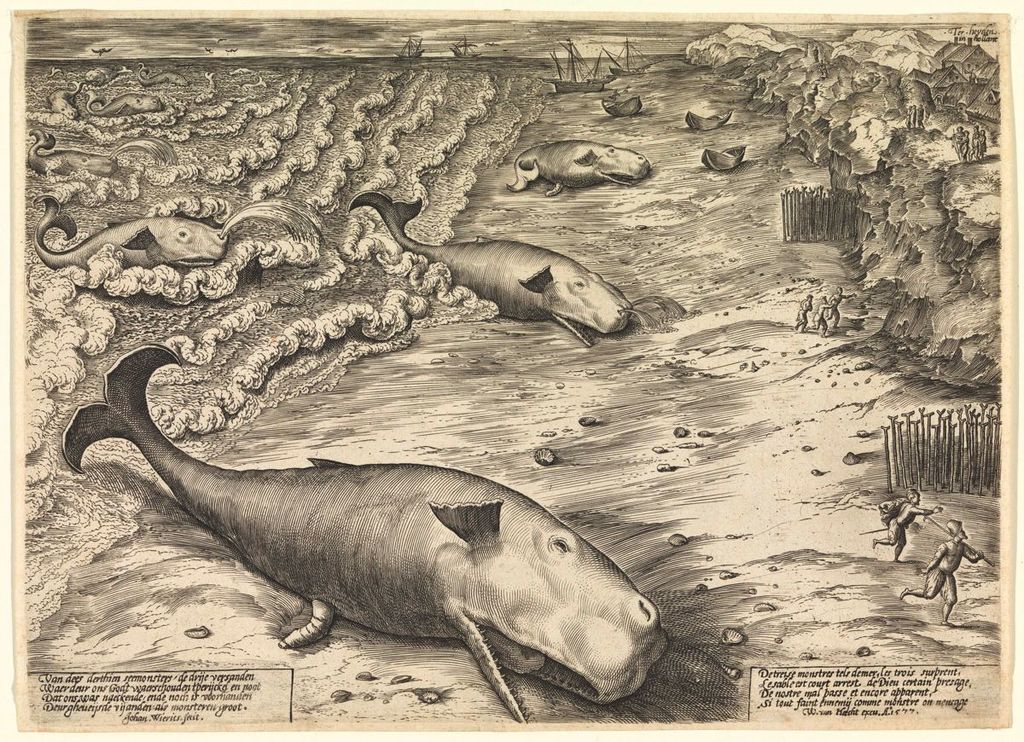

| In 1577, Flemish artist Jan Wierix engraved Three Beached Whales, which depicts three stranded sperm whales. |

The 237 stranded porpoises at Noirmoutier would have seemed miraculous both for the number of animals stranded at once and for the timing of the event.

At that time, Noirmoutier was a young and tenuous community still working to establish itself. Philibert founded it while he was in temporary political exile from his position as abbot of Jumieges in Normandy. Though the island was at an important strategic point in trade routes and benefited from the established salt trade, the fragile community appears to have suffered frequent shortages.

In the medieval world, cetaceans and large fish supported human economies and diets. Their meat could be preserved and eaten (and as an added boon, as fish, could be eaten during Lent and on feast days); their oil could be melted down and used in lamps; their bones were used for tools, as building materials, and in art objects. An English abbey included ten porpoises in its preparations for a feast during the 13th century—yet this seeming abundance is rare. A more common yield might be like that of the fishermen of Kent whose catches “rarely exceed[ed] two a year.”

Olaus Magnus, a sixteenth-century author, provides evidence for the treasure of resources that a single stranded whale could provide: “When sea-monsters or whales have been hauled out of the sea…the people of the neighborhood divide the booty…in such a way that with the meat, blubber, and bones of a single whale or monster they can fill between 250 and 300 carts. After they have put the meat and fat into vast numbers of large barrels, they preserve it in salt, as they do other huge sea-fish.”

Further evidence of the utility of such carcasses is found in the Canons of Adomnan, a set of dietary laws collected in 7th/8th century Ireland. The first canon deals with what was a rare exception to a ban on the eating of carrion: “Marine animals cast upon the shores, the nature of whose death we do not know, are to be taken for food in good faith, unless they are decomposed.”

The Human Culture of Whales

In the miracle story, the unexpected provision of large marine life was interpreted as an omen of prosperity, as a sign that God supported Philibert and his monks in their establishment of the island community.

|

| Jan Saenredam's Beached whale near Beverwijk, engraved in 1601. |

Pre-modern artists in Europe and America were drawn to whales because of their symbolic and economic value. Engravings and paintings show a fascination for the dead and dying leviathans and a kind of boisterous celebration. This is exemplified in Jan Saenredam's “Stranded Whale near Beverwyck” (1602) in which crowds of onlookers flock around the stranded giant (whose dimensions are recorded), climbing on it, celebrating it, drawing it, staring at it—it is a town holiday.

Yet over time, these representations changed. Many modern artists shy away from glorifying whale death—the stranded whale becomes a symbol of impotence (of nature, and of people to save nature), of nature “out of place” and something to be pitied and mourned.

|

| A tail view of Adrián Villar Rojas’s My Dead Family. |

An example that I find particularly resonant of this is Adrián Villar Rojas’s 2009 work, “My Dead Family” which was part of the “the 2nd Biennial of the End of the World” in Argentina.

A recently publicized example of the transformation of whales in art is Hendrick van Anthonissen’s "View of Scheveningen Sands," (ca. 1641), which was recently restored to reveal a beached whale as object of fascination for the Dutch sea-goers. At some point in the 18th or 19th century, a painter covered over the whale with a bland ocean scene with a sailing ship, the crowd’s interest oddly inexplicable.

|

| The restored image of Hendrick van Anthonissen’s View of Scheveningen Sands revealed the beached whale that attracted the sea-goers. |

The scope of the “revision” of the painting caught the attention of the media, but is also clearly of interest to environmental historians, as the literal erasure of the whale is evidence for changing cultural ideas about the meaning of these beachings. As commercial whaling increased and modernized, perhaps the sight of a dead whale became both less unusual and less appealing.

Marine Mammals in Recent Times

Our modern responses to cetacean strandings are vastly different than those of medieval Europeans. In the eighth century, the beaching of a single whale or, in this case, a large group of porpoises, would have been met with celebration, and often a group effort to butcher and preserve the animals.

Today, such an event would also be met with communal labor, but directed (generally) first towards the salvation of the animals, and then towards the investigation of causes of death. Instead of being killed and processed (either for food or for fat), whales and dolphins are helped back out to sea if still living, nursed by concerned humans if dying, and either disposed of (through burial, towing to sea and sinking and/or exploding, burning, etc.) or exhaustively necropsied by scientists.

| During yet another incident in 2005, volunteers at Farewell Spit, New Zealand attempt to keep up the body temperatures of beached pilot whales. |

Indeed, one recent stranding that was treated as a resource in the traditional sense is now held up as a cautionary tale (and the subject of medical and laboratory inquiry). In 2012 a group of Alaskan Inuit consumed a stranded beluga and contracted botulism.

Today, moral, public health, and scientific concerns transform stranded cetaceans from resource into warning. Beachings are carefully and dutifully recorded by teams of activists who race to save stranded mammals—and when MSEs are encountered, they are treated as clarion calls to ocean conservation. (See, for example, the NOAA discussion here.)

Trapped whales convey a sense of nature out of place. The death of a beached cetacean even potentially leads to communal grief and sadness (as in the case famously described by Farley Mowat in A Whale for the Killing, in which the Canadian government eventually found it necessary to issue a formal statement of mourning for the stranded fin whale).

Far from being seen as economic boons, beached cetacea are now economic burdens. A BBC article reports that in 2006, a sperm whale had beached live and died on shore in a remote part of Scotland. Its removal and cremation and disinfection of the beach cost 50,000 GBP. The article points to other disposals of cetaceans as having run to 10,000 and 12,000 GBP.

Finally, today’s whale bodies become fodder not for human sustenance, but for intellectual inquiry through increasingly exhaustive scientific examination.

The marine mammal stranding network explains to the public that the necropsies assist conservation efforts: “In the past few years, increased efforts in examining carcasses and live stranded animals has increased our knowledge of mortality rates and causes, allowing us to better understand population threats and pressures.” (See this NOAA site) Their bodies often do not return to the food chain (unlike, for instance, the phenomenon of the “whale fall” in which whale carcasses become benthic ecosystems).

|

| Inuits continue to "hunt" or "cull" whales in Alaska in traditional boats, much like the one pictured here. |

In North America, Inuit practices are occasionally brought into the discussion as well, but in different ways that emphasize the idea of whales as cultural artifacts, and often in ways that question and critique traditional resource economies.

For example, in 2008, a decision by Inuit leaders to cull almost 600 narwhals led to protests. Tensions can be seen between ideas of whales as resource and whales as scientific object, as the “hunt” or “cull” (the term seems to have been contested in media coverage) produced not only animals that were harvested for meat but also “specimens” that were tagged and tissue samples taken.

Similar tensions are at play in the Faroe Islands’ whale cull, where conservationists have now enlisted the help of filmmaker David Attenborough in their efforts to stop the traditional cull.

From the Medieval to the Modern

At first, it seems that the modern and pre-modern responses to beached marine mammals could not be further apart. Whereas for millennia, humans have turned the death of the animal into a resource and incorporated it into human survival and sustenance, today it may appear that we “waste” the dead and dying animals.

Yet beneath the striking surface differences, a common concern emerges. The scavenging, salvaging, and storage of blubber, meat, and bones in the pre-modern world was of course an economic response to a natural boon—but it was a response that was based on a fear of scarcity. Abundance could be rare and fleeting, as the context of famine in Noirmoutier demonstrates. God could both reward piety and warn about scarcity with abundance through the saints and the natural resources they provided in excess.

|

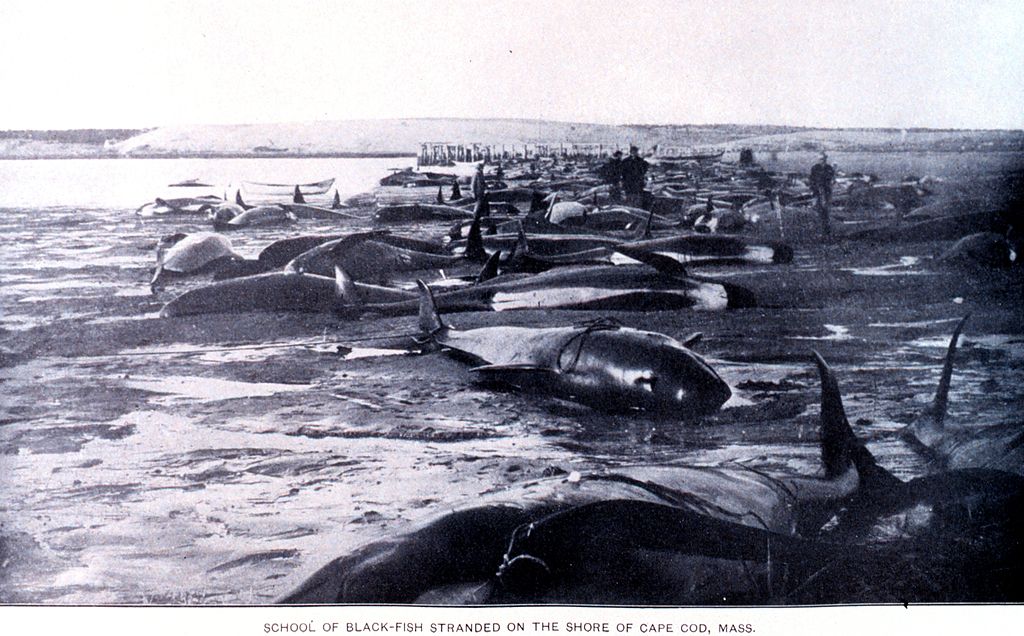

| North American coasts have also experienced MSEs, such as this school of black-fish stranded in 1902 on the beach of Cape Cod. |

In the modern world, we are also deeply concerned with scarcity and abundance—through the lens of science, we count beached porpoises as a kind of a measure of and a talisman against our fears about marine scarcity. These efforts, part of a larger global conservation movement, use advocacy programs to call attention to the dead mammals in the hope that new kinds of environmental piety might provide renewed marine abundance.

As conservationists look for more effective and resonant ways to invoke action aimed at the preservation of marine resources, they may find useful ideas in the actions and ethics of the pre-modern world, and in the deeper history of Christianity.

Last summer, Pope Francis, who named himself after a medieval saint closely associated with environmentalism, issued an encyclical on climate change. Evangelical and Anglican leaders in America have already begun to reframe climate change as a religious and moral concern. In the quest to win converts to marine conservation, stepping beyond a modern understanding of marine life, and beyond a restricted (and negative) view of Christianity and ecology may help yield, as it were, a greater catch.