Although Americans today may take the tactical and operational brilliance of their military forces for granted, such has not always been the case. Perhaps no historical event illustrates the potential disaster awaiting military forces put in a hopeless strategic situation than the fall of the Philippines in the spring of 1942.

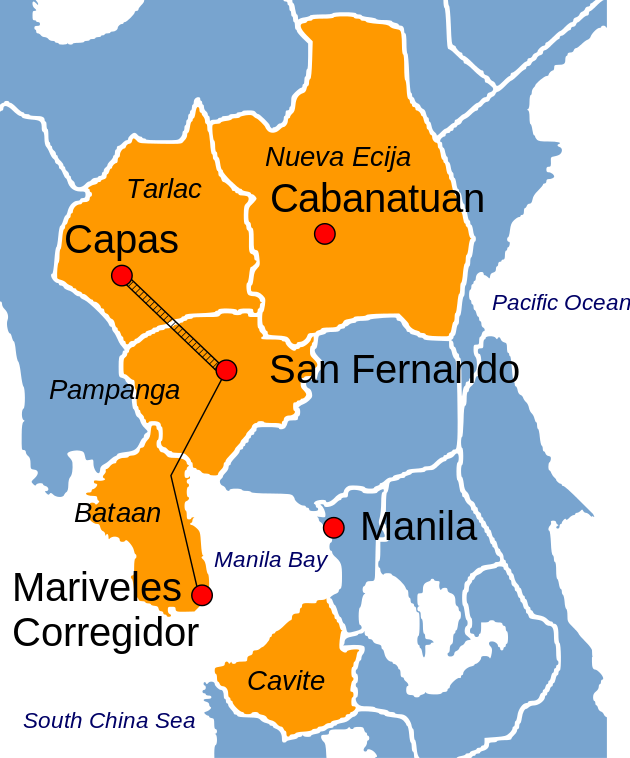

Route of the Bataan Death March.

Following strategic surprise and defeats at Pearl Harbor, Guam, Wake Island, the Java Sea, and Singapore, the surrender of tens of thousands of U.S. and Filipino soldiers to the Japanese in the Philippines stunned the American people and filled them with a burning desire for revenge. The result was what historian John Dower dubbed a “war without mercy” waged throughout the Pacific, ending only with the atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

American military leaders understood that in the event of a war with Japan, the successful defense of the Philippines was problematic at best. With the exception of one division of American regulars and a few capable Filipino formations, the territory lacked a well-trained and equipped military force that could repel a determined invasion backed by strong air and naval forces. U.S. military leaders crafted War Plan Orange with these limitations in mind.

In the event of a war with Japan, U.S. forces in the Philippines would withdraw to the Bataan Peninsula near Manila and await relief, presumably from a naval task force that would defeat the Imperial Japanese Navy along the way. Of course, military planners did not take into account the loss of eight battleships at the onset of the conflict, four of which now rested on the bottom of Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands.

War Plan Orange also did not take into account the mercurial personality of General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the U.S. and Filipino forces. Overconfident that the Filipino soldiers he had trained could stand up to Japanese regulars and overlooking the fact that his air force had inexplicably been largely destroyed on the ground on the first day of conflict, MacArthur moved his forces and the supplies that sustained them forward to confront a Japanese invasion at Lingayen Gulf in northern Luzon.

The better trained and led Japanese army quickly defeated the more numerous Filipino and American forces, forcing them to withdraw. Instead of returning to a Bataan peninsula fortified and stockpiled with supplies for a lengthy siege, the Filipino-American forces were forced to abandon a large portion of their supplies during the retreat.

The troops immediately went on half rations; by the end of the fighting four months later they were on quarter rations. (Troops in intensive combat require 3,500 calories per day. U.S. and Filipino forces in Bataan averaged 2,000 calories per day in January, 1,500 calories per day in February, and 1,000 calories per day in March and April.) As a result, the tens of thousands of American and Filipino soldiers who entered Japanese captivity in April 1942 were already suffering from malnutrition and disease.

The Japanese intended for captured Filipino and American soldiers to march the roughly sixty-five miles from the Bataan peninsula to a railhead inland, from which they would be moved by train to a prisoner of war camp. The victors, however, were unprepared for the tidal wave of around 75,000 prisoners (65,000 Filipino, 10,000 American) who fell into their hands. Food, water, medical care, and transportation were in short supply. The poor condition of the troops left many of them in desperate shape as they were forced to endure 5 to 10 days of marching in the hot sun.

Japanese cultural attitudes made matters much worse. The Japanese considered surrender dishonorable; their troops were encouraged to commit suicide rather than fall into enemy hands. As a result, Japanese soldiers by and large were brutal captors. More than a third of U.S. soldiers taken prisoner by Japan during World War II died in captivity, compared to just 1 percent in German captivity.

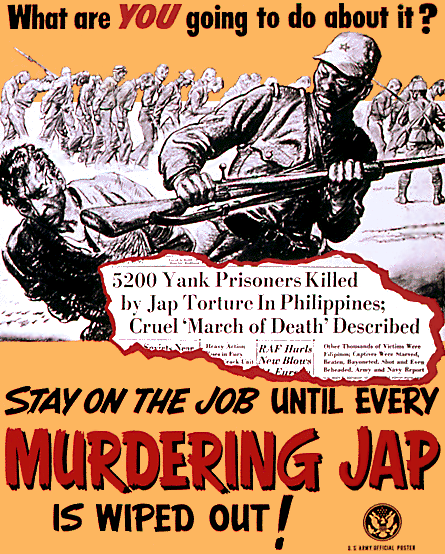

Japanese soldiers denied basic needs – especially water – to the prisoners of war trudging along the dusty roads of Luzon. Soldiers who fell out of the column were beaten, bayonetted, shot, and occasionally beheaded. Although researchers still debate the numbers, it is reasonable to conclude that several thousand Filipinos and several hundred Americans were killed on the march, with as many as 30,000 dying of disease within weeks after entering captivity.

The news of the “Death March” eventually leaked out of the Philippines with prisoners who escaped to Australia. The U.S. government in time released some of their testimonials, and a Life magazine story in February 1944 highlighting Japanese atrocities thoroughly enraged the American people.

When U.S. troops returned to the Philippines, Gen. MacArthur took great risks to liberate prisoner of war camps before the Japanese could kill their captives. In one notorious incident in the province of Palawan on December 14, 1944, Japanese soldiers murdered 139 U.S. prisoners of war by setting fire to trenches in which the men were taking refuge during an air raid. After the war the Japanese commander in the Philippines during the fall of Bataan, General Masaharu Homma, was tried for war crimes, convicted, and executed by firing squad.

The American people would do well to remember their own history when it comes to the just treatment of prisoners of war, lest we commit actions that, like the Bataan Death March, serve to enrage the enemy, motivate his supporters, and turn world opinion against us. The abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in 2003 and statements made in the recent presidential campaign seemingly condoning the use of torture against detainees suggests we may have already forgotten.

Learn more about the Bataan Death March:

· Stanley L. Falk, Bataan: The March of Death (New York: W. W. Norton, 1962)

· Donald Knox, Death March: The Survivors of Bataan (Orlando: Harcourt, 1981)

· Manny Lawton, Some Survived: An Eyewitness Account of the Bataan Death March and the Men Who Lived Through It (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2004)

· Commander Melvyn McCoy, Lieutenant Colonel S. M. Mellnik, and Lieutenant Welbourn Kelley, “Death was part of our life,” Life, 16:6 (February 7, 1944): 26-31, 96-111.

· Michael Norman and Elizabeth Norman, Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009)

Learn more about the Pacific War:

· John Dower, War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986)

· Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991)

· Edward J. Drea, Japan’s Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853-1945 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), p. 260.