In late December 1979—thirty-five years ago this month—the Soviet army entered Afghanistan to stabilize the pro-Soviet Afghan government and offer support in its fight with rebel forces. After almost a decade of occupation, in February 1989—twenty-five years ago—the Soviet Union completed withdrawal of its combat forces across the Friendship Bridge from the Afghan city of Hairatan into Termez, Uzbekistan.

The Soviet leadership’s initial plan for a short intervention lasting six months turned into a long and bitter engagement because in the context of the Cold War, losing Afghanistan, in the words of the Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko, would mean a “sharp setback to our foreign policy.”

| The last Soviet forces leave Afghanistan via Friendship Bridge in February of 1989. |

As the United States haltingly finishes up its long presence in Afghanistan, there is much to learn from the Soviet experience about the type of legacy that the U.S. will have on the country and its people. One of those legacies will surely be architectural.

Though the Soviet Union departed Afghanistan 25 years ago, its decade-long presence left the country’s capital, Kabul, with an abundance of yellow Soviet-made Volga cabs, a spate of new industrial enterprises, and an increase in the number of medical clinics, academic institutions, and urban transportation infrastructure.

It also left a rebuilt skyline.

Today, the most visible remnants of the Soviet era in Kabul are the prefabricated concrete residential complexes known as mikrorayon (from the Russian). They stand alongside mud houses clinging atop mountains and the traditional brick and wood houses of the inner city. And they were designed as a means to use architecture—especially architectures of living spaces—to transform the social and cultural practices of Afghans to match Soviet visions of modernity.

Mikrorayon construction came in two waves: four-floor apartment buildings built beginning in the 1960s (when the Soviet Union began investing heavily in Afghanistan) and then six-story buildings that grew up into the sky in the 1980s during the invasion.

Initial construction of the buildings in the 1960s in Kabul, which the American architect Ada Louise Huxtable (in a New York Times piece) fondly called “an architectural sputnik,” took place in a time of relative peace. Inhabited not only by the elites and the growing (bureaucratic) middle-class but also by members of the working classes, these buildings were to be “a reflection of the new society” and “at the same time the mold in which that society was to be cast.”

The Soviet modernist architect Anatole Kopp wrote that “new architecture is born not only of the experimental and inventive spirit of its creators, not only of technical advances but, above all, of the problems with which history suddenly confronts society.”

Kopp saw the Bolshevik Revolution as an event embodied in modernist architecture, but also facilitated and constructed by it. Similarly, throughout the Soviet occupation, Kabul was under construction and transformation, with the mikrorayon complex meant to serve as the reflection of a new society.

Later, in the late 1980s, a New York Times reporter described the building of the mikrorayons as the development of “a miniature Moscow that is the center of a separate and reclusive world occupied by thousands of Soviet civilians.”

Soviet leaders expected that these developments would show the local population in Soviet-occupied Kabul that there was a positive side to accepting their rule. Of course, these modernization attempts were poor compensation, in the eyes of the majority of Afghans, for the havoc brought by the war.

|

| A six-story, Soviet-built mikrorayon in Kabul, 2010 (Photo by Michal Hvorecky) |

The war quickly confronted the residents of Kabul with unanticipated problems. If the apartment complexes started as signs of social change and progress, with the arrival of the Soviet military and the increased shelling of the city, they had to be adjusted to conditions of regress wrought by war.

Running water and electricity were only intermittently available and almost completely unavailable with the start of the civil war in 1989. Residents had to dig water wells or travel to other neighborhoods that contained them. Due to rocket shelling, windows had to be taped to prevent injury from glass shards, and basements came to function as (civilian) bunkers. Cheap, but not always safe, traditional heating systems (or sandali stoves), sunlight, and gas or kerosene lanterns replaced electric equipment.

The U.S. architectural legacy will be quite different.

Since American and NATO intervention, the Kabul skyline has gradually become dominated by an eclectic assortment of high rises, new shopping centers, and skyscrapers built by the country’s super rich.

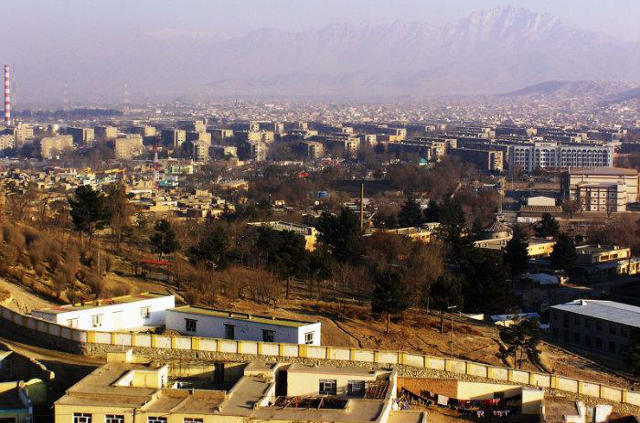

|

| Kabul’s skyline, as seen here in 2010, is sure to be transformed once again since American and NATO intervention. (Photo by Robert Sanchez) |

The new buildings are towering expressions of individual tastes, and stand as a stark contrast to the grey mikrorayon apartment buildings that were initially meant as “a public statement” to illustrate “the collective spirit” and to provide modern forms of housing to a large group of Kabul’s urban dwellers.

|

| Stanikzai City is one such example of the new luxury development taking place. These are found 3km from downtown Kabul. |

Of the luxury high-rise buildings in Kabul, a South African urban planner, Jolyon Leslie, recently said, “looking at these awful buildings . . . kills me as an architect, but from an economic point of view it seems to be quite a vote of confidence.”

If architecture is, in any way, indicative of individual tastes, then these buildings are certainly signs of individuality, in addition to economic growth. Instead of exemplifying the “transforming of mankind,” Kabul’s skyline now expresses a spirit of urban individualism, even if “awful” and indifferent to the masses making as little as $1 a day.