This year marks the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, the medieval English historic legal document that is seen as the origin of many modern-day legal rights and constitutional principles.

By June 1215, England was in civil war as disaffected barons took up arms against King John (reigned 1199-1216). John’s reign had been marked by a seven-year conflict with the papacy that led to an interdict (ecclesiastical censure) in England and to his own excommunication, the troubling loss of his French possessions, and deep distrust between him and his barons, who thought he was abusing royal power.

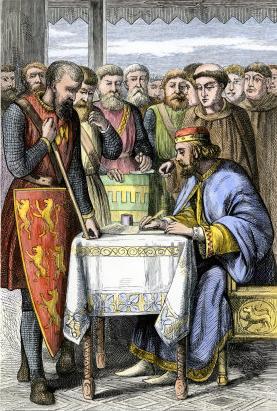

When the rebel barons seized London, King John was forced to capitulate to their demands. Meeting on a field at Runnymede, the king and barons agreed on June 15 to a set of provisions that would become known as the Magna Carta, or Great Charter, of England.

Essentially a peace treaty, the Magna Carta protected the traditional feudal rights of the barons and attempted to curb the abuses of John’s government. In that sense, it was a failure: it was quickly annulled by the pope, and England plunged further into civil war. Yet today it is considered one of the most important documents in Anglo-American legal history as the foundation of concepts such as due process and limited sovereignty.

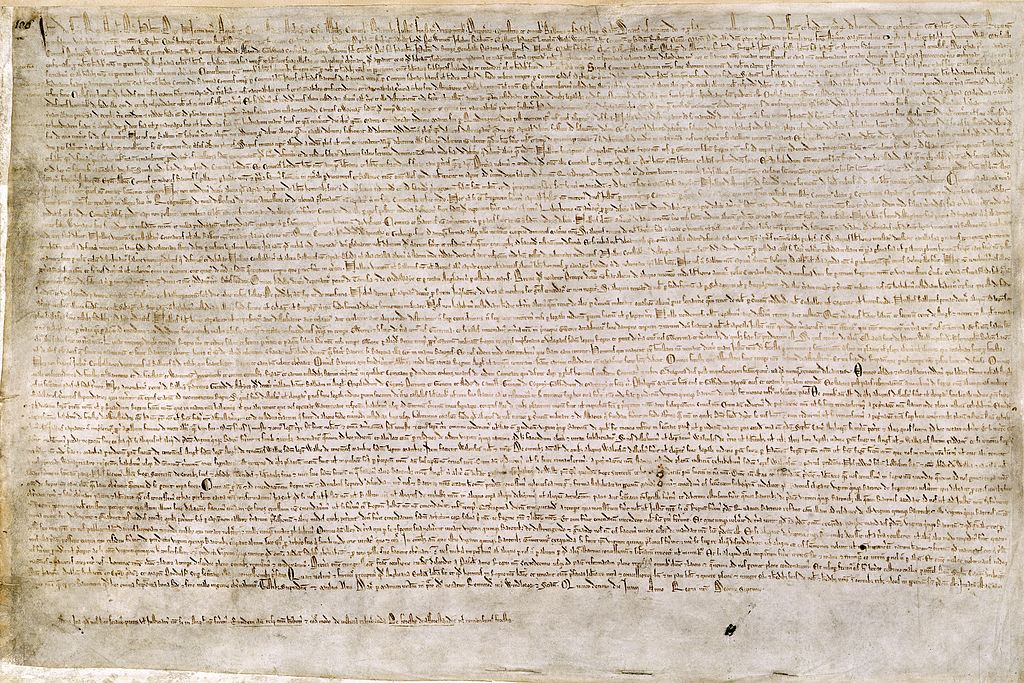

Modern scholars debate whether the Magna Carta is a conservative document that sought to restore traditional feudal rights or a revolutionary social contract that asserted new individual rights and limited the powers of the sovereign. Although many of its 63 clauses condemn specific aspects of John’s rule, others are more clearly reactions to twelfth-century advances in royal administration that threatened baronial power.

What is clear is that some clauses had a lasting effect on the development of English law and government. For example, clauses 12 and 14 impose limitations on the king’s ability to demand feudal aids without consent, which contributed to the development of parliamentary control over taxation.

Perhaps the most important clause, however, is clause 39: “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.”

This clause establishes the concept of due process of law. By stating that the government could not act against the people outside of the legal system, it also asserts that the sovereign is not above the law, an important idea in the gradual development of constitutional monarchy and limited sovereignty.

Although it was regularly confirmed by English kings during the medieval period and was entered into statutory law in 1297, over time Magna Carta became more important for what it symbolized than for what it contained.

After being mostly ignored for several centuries, it was resurrected by seventeenth-century jurists, who read in it a guarantee of individual freedoms and limited monarchy in the struggles against the absolutist kings of the royal house of Stuart. During this period, it came to represent the idea that a government could not arbitrarily alienate the rights of its citizens and to guarantee the rights of trial by jury, habeas corpus, and no taxation without representation.

It is this understanding of the Magna Carta that was exported to the American colonies, where it was seen as the embodiment of colonists’ rights as English citizens. It served as a precedent for the Declaration of Independence and the source of many of the rights and principles enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights. Later, it would also influence the constitutions of many Commonwealth nations, as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the European Convention on Human Rights (1950).

Today, we tend to take the rights symbolized by the Magna Carta for granted, yet many inform ongoing debates about our civil liberties. Eight hundred years later, we are still debating and defining the rights that originated on the field at Runnymede.