When was the last time you used a landline phone to make a long-distance call? If you’re like me, it’s probably been a while. The New York Times noted that only “about half of American households had a landline” phone in 2015, down from roughly 90 percent just eleven years earlier. Today, the practice of picking up a phone wired to a wall-mounted jack seems simply passé, a relic of a long ago past. If you want to get a hold of someone in the age of the Internet, you just pick up your iPhone and use an app (maybe Skype, maybe FaceTime) to unlock portals of communication.

Apple’s original iPhone, released in 2007.

Yet, if we pause to consider two anniversaries this month—the opening of the first commercial transatlantic telephone service on January 7, 1927 made possible by American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) and the introduction of Apple’s iPhone in January 9, 2007 –it’s worth considering how today’s transformative technologies still depend on the innovative infrastructure of the past.

After all, Steve Jobs’ iPhone—clever as it is—has no power without the technological breakthroughs associated with AT&T’s old landline technology. Without the cables that connect machines on the Internet, the iPhone would be a dead hunk of plastic and rare earth metals. This new technology is very much tethered to the past—to a web of lines that crisscross our nation and globe.

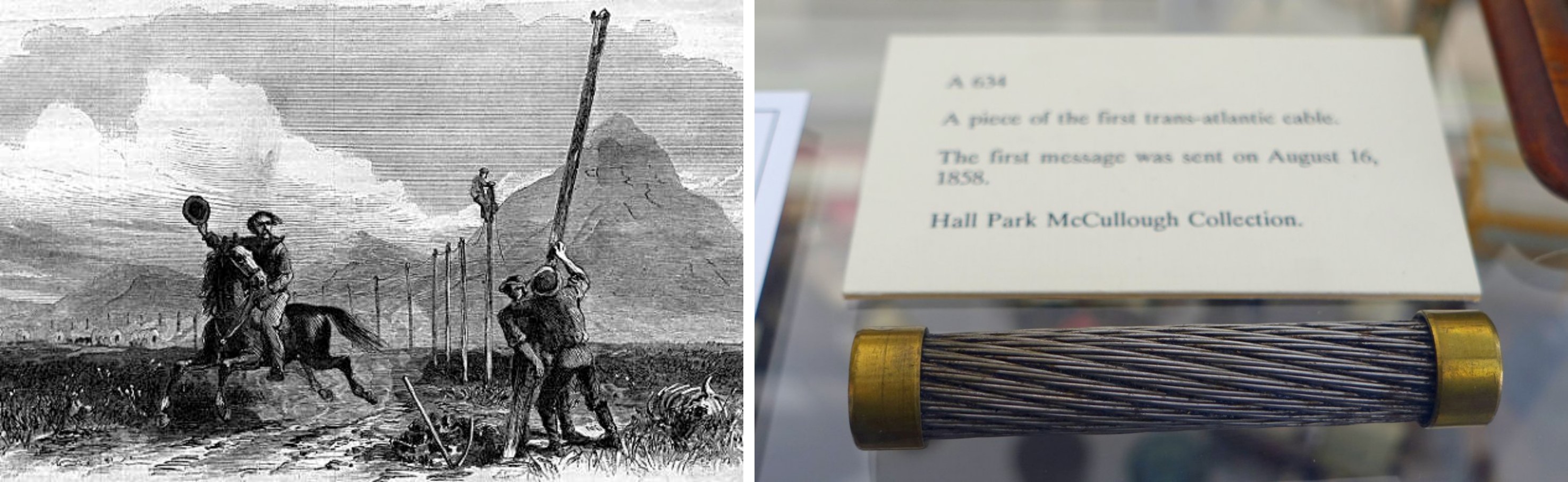

In fact, the real origins of the iPhone’s power stems from the pioneering efforts of communication innovators that preceded the AT&T engineers of the 1920s. The story of wired long-distance communication really begins with the Western Union post-diggers who laid the first American transcontinental telegraph in 1861 and the Atlantic Telegraph Company that dropped the first transatlantic telegraph cable into the Atlantic Ocean in 1858. (An effective transatlantic telegraph system would not officially emerge until the 1860s when cables were improved to endure oceanic conditions.) Here were developments that transformed global capitalism, allowing businesses in the following decades to communicate commercial transactions swiftly over vast geographic spaces.

Engraving depicting the first transcontinental telegraph (left) and a segment of the first transatlantic telegraph cable (right).

But even if American business had the means of communicating via telegraphs with European business partners by the early twentieth century, prior to the 1920s, they did not have the ability to actually talk with oversees partners via a phone. Yes, Alexander Graham Bell had invented the telephone in 1876, and in 1915 he made the first transcontinental telephone call over AT&T wires that extended over 3,000 miles from New York City to San Francisco. But by the early 1920s, businessmen still had no effective way of having a telephone conversation across the Atlantic Ocean.

That’s why that transatlantic phone call between AT&T president Walter Sherman Gifford and General British Post Office official Sir Evelyn P. Murray on January 7, 1927 was so important. Finally, American businesses could communicate in real-time by voice across the ocean with commercial partners in Europe. And business exchanges began almost immediately after Graham and Murray finished their initial chat, as heads of major firms got on the phone to talk trade. Some reports suggest that over $6 million in business transactions transpired via voice communication on that day.

President of AT&T Walter Sherman Gifford, 1925.

But even then, the communication revolution was still incomplete because that first call was actually transmitted via radio waves through the air. Sure, the ability to send voice communication from the US to Europe was a vast improvement over telegraphic correspondence, but radio transmissions could be unreliable, contingent upon the proper weather conditions and other factors that could affect the quality of wave signals sent thousands of miles across an ocean. For capitalists seeking consistency in their everyday transactions, this was a real problem.

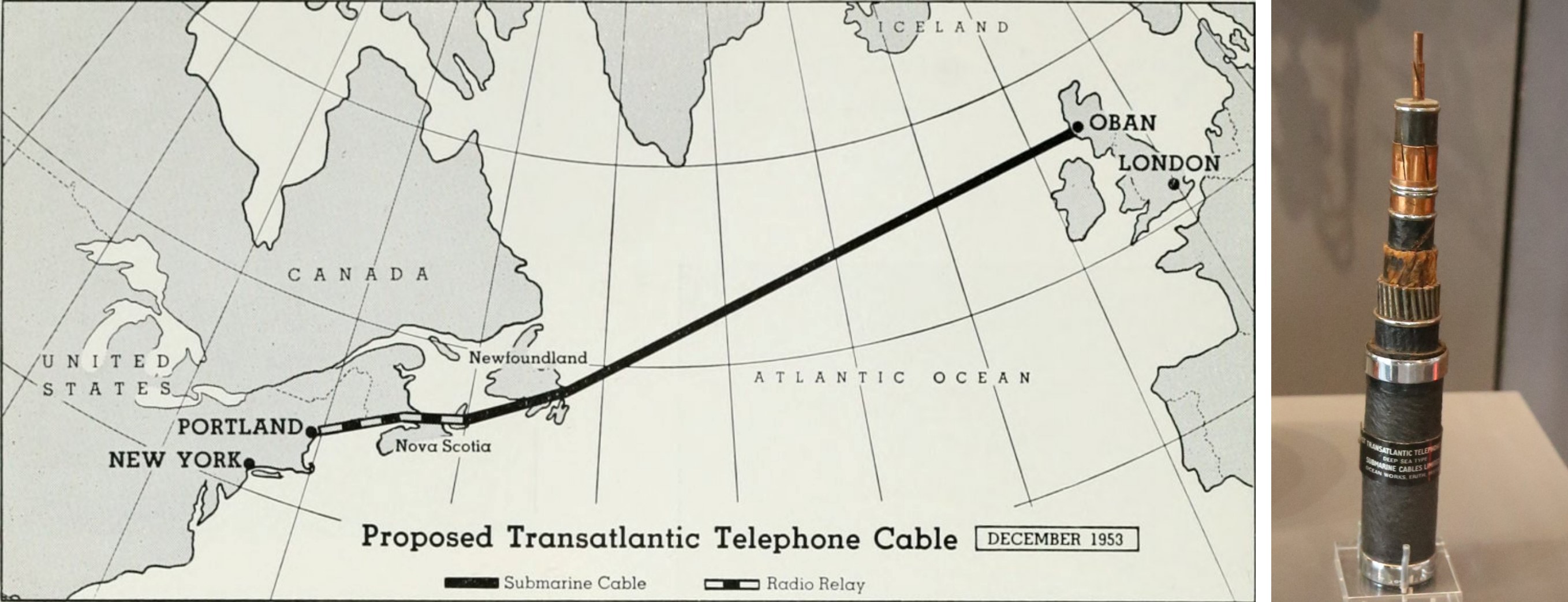

That problem was overcome in 1956, when AT&T, working with the British Post Office and Canadian partners, laid the first transatlantic telephone cable known as TAT-1, which was a plastic-insulated transmission system capable of sending underwater telephonic signals from Newfoundland to Scotland.

Map of proposed telephone cable (left) and the layers of a TAT-1 cable (right).

It had taken roughly thirty years to develop lines with repeater technology that could boost voice signals at various intervals along transmission routes, thereby ensuring that the volume of someone’s voice on one end of the telephone line did not diminish considerably by the time it got to its final destination. Finally, roughly a century after the first transatlantic telegraph had connected the Old World with the New, AT&T and its partners had found a way to make cabled voice communication across the pond possible.

And this is where the story of the iPhone and AT&T really fuse. AT&T took lessons learned about wired communication (lessons that in some ways dated back to the telegraphic age of Western Union in the 1860s) to help construct a new communication web that could allow computer systems to communicate with one another.

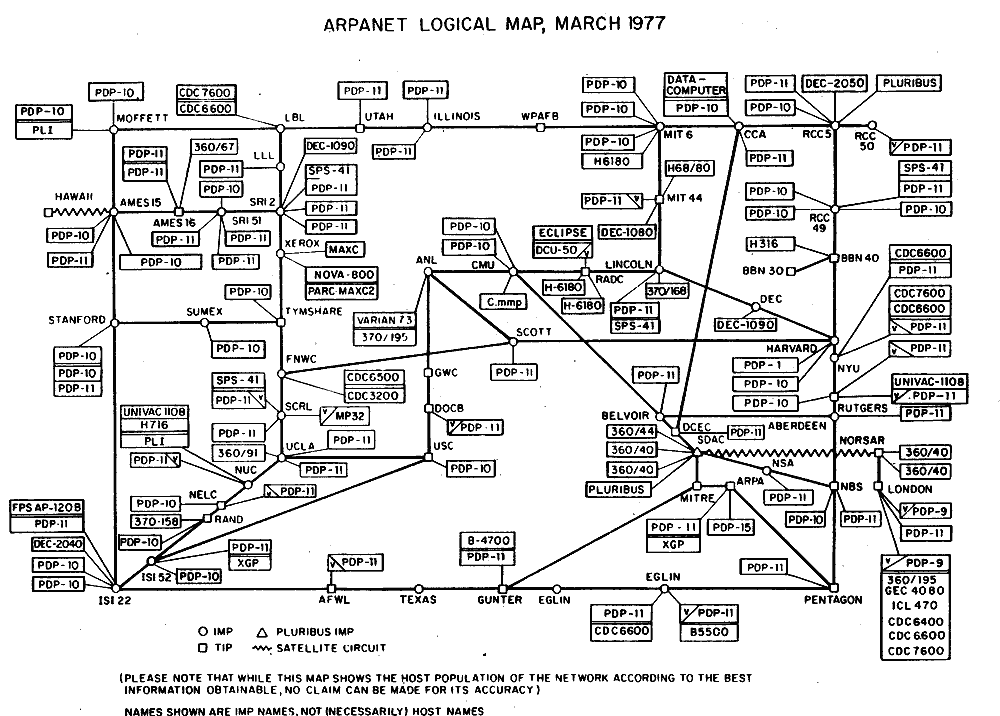

In 1969, when the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Project’s Agency (DARPA) proposed connecting mainframe computers via a wired network called ARPANET, AT&T helped build the connection between research facilities at Stanford, the University of Utah, The University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of California, Santa Barbara. Thus was born the primitive foundation of what we now know as the Internet.

Interestingly, the Department of Defense asked AT&T if they wanted to take over ARPANET and manage it a few years later, but AT&T begged off. Nevertheless, AT&T continued to lay cables, like the first transatlantic fiber-optic TAT-8 line, which was a foundational channel that paved the way for global Internet transactions thereafter.

Today, we don’t use many of the first transoceanic cables laid back in the day. In a lot of places, we now have new fiber-optic cables that have replaced older lines. But, we nevertheless live in a world of webbed cables, one that owes its origins to AT&T and Western Union’s innovations years ago. Today, over 95 percent of all Internet traffic between nations separated by oceans still goes through cables that are underwater.

The ship Ile de Sein laying fiber-optic cable off the west coast of Canada, 2007.

So, when Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, calling it a “revolutionary product . . . that changes everything,” he was only partially right. No doubt, our world is very different because of Apple’s signature phone, but Jobs’ creation is as much a harbinger of the future as a product of the past. Our iPhones are still very much linked to a buried history—one that may be under oceans, but nevertheless still connects our world today.