In the 50 years since they first went on display, Andy Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans have become a canonical symbol of American Pop Art. Warhol, an American commercial illustrator from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania turned fine artist, author, publisher, painter, and film director, first showed the work on July 9, 1962 in the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, California. It was his first solo exhibition. The show was largely uneventful. Few people attended (not even Warhol), and afterwards a secondary showing planned for New York later that year was canceled.

Today though, Warhol has his own museum in Pittsburgh and his 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans is one of the prized pieces at the New York Museum of Modern Art. An earlier, single canvas version (Campbell’s Soup Can (Tomato) sold through Christie’s Auction house in 2010 for over $9 million.

32 Campbell’s Soup Cans consists of thirty-two 20”×16” screen-printed canvases, one for each of the varieties sold at the time. They were originally presented linearly, resting on a shelf mounted on the wall in an effort to mimic the grocery store shopping experience.

For viewers today, the series tends to evoke nostalgia. Each print has slight variation due to the inconsistency of the silk-screening process and manual finishing details, and together, they appear “touchingly handmade.” In a world saturated with high-tech media marketing and airbrushed ads, it can be hard to imagine that in the 1960s, Warhol’s now ubiquitous art was criticized as sterile, cold, and mechanical.

At the time, Abstract Expressionism, featuring artists such as William de Kooning, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko, and privileging human emotion, painterly styles, and “fine art” aesthetics, was the movement to watch. Pop Art by contrast embraced mundane commercialism. Contemporary interpretations of Pop Art ranged from a subversive critique of American consumerism and a warning about the shrinking gap between human and machine, to a legitimation of the joy products bring to our lives.

Warhol himself once described Pop Art as “liking things.” When asked why he painted soup cans, he replied, “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years … the same thing over and over again.”

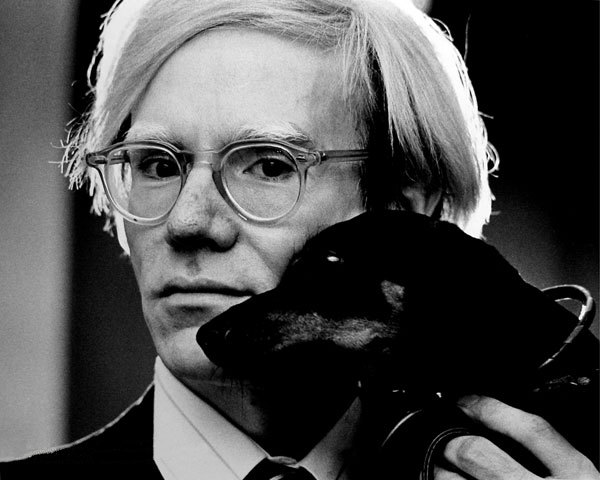

Like the commodities he drew inspiration from, Warhol fashioned himself as a commercial product. He worked out of a studio he called the “Factory,” employed an “assembly-line” technique, and his very persona seemed designed as a product for public consumption: plastic, image driven, devoid of a “narrative sense.”

Thus, Warhol’s “true” personality, like his art, is hard to grasp. While divesting himself of individuality, he was also a master self-promoter, and, though billed as a prankster, he never gave up the act. Even his autobiographical 1975 “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol” is “a parody of personal revelation,” full of hollow banality, constantly reasserting the author’s own “nothingness.”

Nevertheless, Warhol’s presence in art and popular culture has been huge. Works like Green Coca-Cola Bottles (1962, above) and Brillo Boxes (1964) pushed the public to think about material consumption, while his reproductions of news articles depicting horrific car accidents and portraits of tragic celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor, and Elvis Presley made us think about our relationship to news and entertainment, and what that relationship said about us as a society.