African Americans demanded justice after the tragic killing of teenager Trayvon Martin, but a jury in Florida failed to convict his killer, George Zimmerman. The case reflects a long history of inequality between African Americans and white Americans in the criminal justice system.

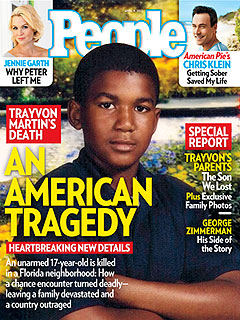

The basic fact was never in dispute: on February 26, 2012 George Zimmerman shot and killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in the town of Sanford, Florida. When a verdict of “not guilty” was announced, African Americans saw the outcome as another painful link in a chain of unpunished cruelty dating back hundreds of years. This month historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries examines the long history of racial violence in America and how the issue of race permeated every aspect of the tragedy from the shooting, to the reluctance of the local police to arrest Zimmerman, to the conduct of the trial itself.

Read Origins for more on American current events and history:“Class Warfare” in American Politics, Detroit and America’s Urban Woes, Mass Unemployment, Populism and American Politics, Immigration Policy, the Mortgage and Housing Crisis, American Political Redistricting, and the American Two-Party System.

After deliberating for sixteen hours, the jurors in State of Florida v. George Zimmerman informed Seminole Circuit Court Judge Debra Nelson that they had reached a verdict.

Zimmerman, a 29-year-old neighborhood watch captain in Sanford, Florida, had been charged with second-degree murder for killing African American teenager Trayvon Martin on February 26, 2012.

Martin’s parents, Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin, had sat through every moment of the three-week trial, but they were not present the evening of July 13, 2013 to hear the verdict. They had left Tallahassee hours earlier. Waiting for the verdict had become unbearable.

On the charge of second-degree murder, the six-woman panel found Zimmerman not guilty. The jury of five whites and one Latina reached the same conclusion on the lesser charge of manslaughter.

Less than an hour after the verdict was announced, Martin’s parents let their voices be heard. Using social media, they expressed their disappointment in the trial’s outcome, pain over the loss of their child, appreciation for the millions who mobilized to support justice for their son, deep and abiding Christian faith, and everlasting love for their dead son.

“Lord during my darkest hour I lean on you,” tweeted Sybrina Fulton. “You are all that I have. At the end of the day, GOD is still in control. Thank you all for your prayers and support. I will love you forever Trayvon!!! In the name of Jesus!!!”

Tracy Martin tweeted, “Even though I am broken hearted my faith is unshattered, I WILL ALWAYS LOVE MY BABY TRAY.” He added: “God blessed Me and Sybrina with Tray and even in his death I know my baby proud of the FIGHT we along with all of you put up for him GOD BLESS (sic).”

As word of the not-guilty verdict spread, spontaneous protests erupted in cities across the country. From Miami, Florida to Oakland, California, thousands took to the streets to vent their anger and frustration. In Washington, D.C., some carried signs that read, “Stop criminalizing black men,” while in New York City others held banners that read, “We are all Trayvon Martin.” Rioting was predicted, but nothing of consequence occurred.

Like the Martins, many people shared their grief and outrage through social media. “How do I explain this to my young boys??” tweeted NBA superstar Dwyane Wade.

Others used social media to express their dissatisfaction with the spate of gun laws that have made it increasingly difficult to prosecute people who claim self-defense to justify their use of deadly force. “Only God knows what was on Zimmerman’s mind,” tweeted media mogul Russell Simmons, “but the gun laws and stand your ground laws must change.”

Still others drew attention to the long history of racial violence against African Americans, and to the even longer history of perpetrators of such crimes going unpunished.

Benjamin Crump, the attorney for the Martin family, echoed the sentiments of many on social media when he paralleled Zimmerman’s acquittal to that of the white men who murdered 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955. “You have a little black boy who was killed,” he said during a press conference immediately after the verdict was read. “It’s going to be reported in history books and 50 years from now, our children will talk about Trayvon Martin’s case like we talk about Emmett Till.”

The hurt and anger emanating from every corner of the black community was palpable. And while many white Americans shared this sense of injustice, there remained a great gulf separating how African Americans and white Americans made sense of Martin’s death and Zimmerman’s acquittal.

Before the trial and Zimmerman’s arrest, a USA TODAY/Gallup Poll found that 73% of African Americans believed that, if Martin had been white, Zimmerman would have been immediately arrested. Only 33% of whites shared this view.

After the trial, the chasm in perspective remained. According to a Pew Research Center poll, 86 percent of African Americans were dissatisfied with the verdict, as compared to just 30 percent of whites.

The Pew report notes that “nearly eight-in-ten blacks (78%) say the case raises important issues about race that need to be discussed.” Just 28% of whites say the same, “while twice as many (60%) say the issue of race is getting more attention than it deserves.” Other polls found similar if not more polarized results.

The reason for the gap is no mystery. African Americans placed the shooting and trial in historical perspective. They located it on the continuum of anti-black violence, assumed black criminality, and racial bias in the criminal justice system that stretches back generations.

Knowing this history, Ice Cube, who has rapped about the senseless killing of African American men and boys, tweeted: “The Trayvon Martin verdict doesn’t surprise me. Sanford, Florida never wanted Zimmerman arrested. Now he’s free to kill another child.”

White Americans, meanwhile, tended to ignore the racially discriminatory aspects of the black experience, past and present. Instead, they viewed Zimmerman’s actions in isolation, divorcing them from the social and historical reality that informed them. They also fell back on racial stereotypes to explain Zimmerman’s and Martin’s behavior.

There are facts about the night that George Zimmerman shot and killed Trayvon Martin that will never be known for certain because Martin is not here to tell his side of the story.

But it is possible to know why African Americans and white Americans viewed the situation so differently. The key is the historical context that informed African Americans’ understanding of Martin’s murder and Zimmerman’s acquittal.

Racial Violence and the Color of Justice

African Americans made tremendous gains politically and socially immediately after slavery ended in 1865. Drawing on their newly won citizenship rights, they ushered in an era of expanded democracy that saw, in addition to the election of African Americans to state and federal offices, African Americans serving on juries. In the process, they began to transform the South.

But African American advances were short lived. Southern whites clung feverishly to a slaveholder mentality and wanted desperately to reestablish control over black labor.

And so, when southern whites returned to power in the 1870s, they began enacting laws that stripped African Americans of their most basic freedom rights, including equal justice under the law.

The federal government sanctioned the process of turning back the clock. After Homer Plessy challenged segregation on public transportation by deliberately sitting in a whites-only car on a Louisiana railroad, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of segregation.

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) the court ruled that in all facets of public life African Americans and whites could legally be kept separate as long as equal accommodations were provided. The court ignored the fact that separate always turned out to be unequal.

In the wake of Plessy, white southerners rapidly created the extensive Jim Crow system of laws and customs that locked in and enforced southern racial segregation. And whites used violence and terror to ensure that African Americans adhered to the new status quo.

Indeed, violence was the cornerstone of Jim Crow, much as it had been during slavery. It was used to control black labor and regulate black behavior. It took many forms, from beatings and sexual assaults to wanton murder.

The most dramatic form of violence, though, was lynching. Many of these murders were public spectacles, drawing huge crowds. They also frequently involved local lawmen and civic leaders.

Between 1882 and 1930, whites lynched some 2,300 African Americans in ten Southern states from North Carolina to Louisiana. Mississippi led the nation in lynching with over 500, but Florida had more than its fair share. In the history of American race relations, Florida has been no different than the rest of the South.

In Lafayette County, Florida in 1895, three black men were kidnapped by a group of white men. The three were blamed for the death of a white woman, an accusation they vehemently denied. Despite their pleas of innocence, an eyewitness reported: “They were scalped, their eyelids and their noses cut off, the flesh cut from their jaws, their bodies scraped and their privates cut out. The blood flowed in streams from their ghastly wounds, and their screams rent the air only to be silenced by the tearing out of their tongues by the roots.” It perhaps goes without saying that the white perpetrators were not punished for this horror.

Almost anything could trigger an act of racial violence. Violating Jim Crow protocol by failing to say ‘yes sir’ or ‘no sir’ when addressing a white man could lead to a beating, while turning a profit as a farmer could result in murder.

“Abusive language” was a formal, legal charge that landed plenty of African Americans in jail. The informal penalty for “Talking back,” though, could be even higher. In 1890, F. G. Humphreys, the collector of customs at Pensacola, described the consequences of “Talking back” in a letter to U.S. Senator William Chandler.

“Not a great while ago at the River Junction, 22 miles this side of Quincy, a young man by the name of Allison, a native of Quincy, employed by a railroad at the junction, had some words with an employee of the same road, when another clerk said … ‘Here, take my pistol & kill the black son of a bitch,’ this he did, deliberately walking up to the colored man and blowing his brains out! For this crime Allison was never arrested. I am told this by a Democrat, an eye witness to the affair. Such dastardly outrages are of daily occurrence in the South of which you hear nothing, and we are powerless to prevent it.”

The arbitrariness of Jim Crow made every African American susceptible to violence, making it difficult for them to live free of fear.

Racial terrorism was not the preserve of a single group or class of whites. All manner of whites—rich and poor, old and young, men and women, professional and working class—engaged in acts of racial terror.

And rarely did they hide behind hoods. They committed their acts of violence in the open, knowing that sheriffs would not arrest them, prosecutors would not try them, and all-white juries would not convict them.

During the Jim Crow era, the scales of justice were tipped wholly in their favor.

The Tragedy of Emmett Till

Of the many murders of African Americans by whites, young Emmett Till’s death continues to reverberate in the black community. It is hardly surprising, then, that his name leapt from the lips of African Americans nationwide when they learned of the killing of Trayvon Martin and the acquittal of George Zimmerman.

14-year-old Emmett Till lived in Chicago with his mother, Mamie Till, but home for them was Mississippi, where Mamie was born and grew up. In August 1955, Mamie Till sent young Emmett to Money, Mississippi to be with family and friends while school was out, a common custom among black migrants from the South.

Till had only been in the sleepy town a few days when he and several buddies visited a convenience store to purchase candy and cold drinks. But as he left the store, something happened.

On a dare, he might have whistled or said “Bye baby” to the white woman behind the register, Carolyn Bryant, whose husband owned the store. Whatever transpired, Bryant felt insulted and assaulted. Having not grown up in the South, Till did not realize the dangerous line that had been crossed.

A few nights later, Carolyn’s husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, kidnapped Till from his uncle’s home in plain view of everyone in the house. It was the last time anyone saw him alive.

After several days, Till’s severely beaten and mutilated body was found in the Tallahatchie River, having floated to the surface after the cotton gin fan that had been used to weigh it down came loose.

When Mamie Till laid eyes on her son’s swollen and mutilated body, she set aside her own grief and despair and resolved to have an open casket funeral. She wanted the whole world to see what Mississippi had done to her only child. Thousands viewed young Emmett’s body at his funeral in Chicago, and many thousands more saw it when snapshots appeared in Jet Magazine, a popular African American weekly.

Emmett Till’s murder shocked the nation in part because it took place in a new media era when images could be easily spread and it was much harder than in earlier generations to hide the results of lynching and murders.

Those who laid eyes on Emmett’s body would never forget what they saw. It left an especially deep impression on black children Till’s age. For them, it made the horror of white supremacy all too real. They understood that Emmett Till could just as easily have been them.

It also lit a fire under them. Five years later, in 1960, these young people—the Emmett Till Generation—were the same college students who struck a mighty blow for freedom by launching the sit-ins. In an important moment in the larger Civil Rights movement, young African Americans all through the South sat at lunch counters and restaurants in the white seating areas in nonviolent protest of segregation.

Meanwhile, back in Mississippi, Bryant and Milam stood trial for their crime. But an all-white, all-male jury took little over an hour to find them “not guilty.”

A month later, the two men sold their story to Look magazine for $4,000. In the article, they confessed to murdering Emmett Till, and their justification serves as a sobering testament to white racial views in the mid-twentieth century.

“Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless… I like [African Americans]—in their place—I know how to work 'em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, [they] are gonna stay in their place. [They] ain't gonna vote where I live. If they did, they'd control the government. They ain't gonna go to school with my kids. And when [an African American] gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he's tired o' livin'. I'm likely to kill him… I stood there in that shed and listened … and I just made up my mind. 'Chicago boy,' I said, 'I'm tired of 'em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I'm going to make an example of you—just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.”

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s dismantled some of the more egregious laws that sanctioned racial violence, discrimination, and segregation, especially with the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), as well as the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965).

Yet, many attitudes and customs remain unchanged.

The assumption of black criminality is a common thread connecting Till’s death and the acquittal of his murderers with so many other unprosecuted and unpunished killings of African Americans by whites both yesterday and today.

Far too often whites assume that African Americans, especially African American men and boys, are criminals or criminals in training. This kind of racial profiling is wholly divorced from the historical reality of racial violence and lynching, which suggests that African Americans have a whole lot to fear from whites and that whites have far less to fear from African Americans.

But, it was this sort of racial profiling that compelled Zimmerman to initially move on 17-year-old Trayvon Martin.

Every American is exposed to the idea of black criminality. The fact that George Zimmerman was of Hispanic descent, therefore, did not immunize him from these beliefs. He was just as susceptible to them as the average white American.

This sad reality helps explain why so many in the white community embraced Zimmerman as one of their own. They accepted him and his version of events because they shared fully his perspective on black criminality.

When Zimmerman first spotted Martin at the Retreat at Twin Lakes, the townhouse complex where Zimmerman lived, he assumed the lanky young man was up to no good, a thief on the prowl most likely. Zimmerman said as much to the 911 operator he called to report Martin’s presence. “F------ punks,” he said. “These a------ … They always get away.”

It is telling that Zimmerman assumed that Martin was casing the neighborhood, looking for someplace or someone to rob. There are an infinite number of possibilities that might just as easily have explained the youth’s presence, possibilities that Zimmerman most assuredly would have applied to someone other than a young black male.

One possibility was that Martin was simply walking back to where he was staying after taking a trip to the neighborhood convenience store to purchase something as innocuous as a bag of Skittles and a bottle of Arizona iced tea. And while this possibility happens to be true, neither it nor any other legitimate cause for Martin’s presence seems to have crossed Zimmerman’s mind.

Instead, Zimmerman immediately suspected Martin of criminal activity. In doing so, he racially profiled Martin, drawing on the old stereotype that casts black males as perpetual lawbreakers.

What happened next remains in dispute. It is tragically clear, though, that after making contact, Zimmerman shot and killed the unarmed Martin. Zimmerman did not deny this fact; he said as much to the police.

It is equally clear that police officers in this predominantly white suburb of Orlando accepted Zimmerman’s version of things. Without a meaningful investigation, they dismissed the killing as self-defense.

Later, when pressed for an explanation as to why Zimmerman had not been charged with a crime for killing the unarmed black youth, police officials insisted that Florida’s Stand Your Ground law, which permits a person to use deadly force if that person fears death or bodily harm, prohibited them from bringing charges.

Stand Your Ground

Stand Your Ground laws have been introduced nationwide by the ultra-conservative policy group the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and have taken hold in the South as well as in Northeastern and Midwestern swing states. These laws have made it twice as likely that a murder will be ruled a justifiable homicide.

This shift in excusing murder is all the more troubling when one considers the tremendous racial disparity in which homicides are ruled justifiable.

According to research conducted by John Roman, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, even in states without Stand Your Ground laws, 29.3 percent of white-on-black shootings are ruled justifiable, while only 2.9 percent of black-on-white shootings are.

Although law and custom were against them, Martin’s parents were determined to bring their son’s killer before a court of law. So when it became clear that local prosecutors did not plan on charging Zimmerman, they reached out to civil rights activists. Together, they raised national awareness of the case.

As news of the killing spread, African Americans began to mobilize. Thousands descended on Sanford to participate in Justice for Trayvon rallies. An online petition started by Martin’s parents demanding that Zimmerman be prosecuted collected more than two million signatures.

The fervent response of the black community demanding that Zimmerman be brought to justice stemmed from collective memory of the tragically long history of white Americans killing African Americans and never having to stand trial for their crimes. Also on the minds of African Americans was the painful realization that black men and boys could still be killed for doing nothing other than minding their own business.

African Americans reacted so viscerally to Martin’s death and the failure of police and prosecutors to do anything about it because they understood that Martin’s fate could just as easily be their own, or that of a brother, son, father, uncle, nephew, or friend.

When African Americans looked in the mirror or laid eyes on loved ones, Trayvon Martin stared back. Speaking about a week after the trial and in unusually frank and personal terms about racism and American history, President Barack Obama remarked: "Trayvon Martin could have been me, 35 years ago.”

As the grassroots mobilization grew, so too did the rallying cry, “I am Trayvon Martin.”

Race and the Court Room

Forty-four days after the shooting, police finally arrested Zimmerman. Responding to the public outcry, the office of the state’s attorney general investigated the incident and found just cause to charge Zimmerman with second-degree murder, meaning the state believed he acted with a depraved state of mind, ill will, hatred, or spite.

One year later, when Zimmerman’s trial began, African Americans followed it intently. The prosecution’s approach, however, left many bewildered. Although racial profiling sparked the chain of events that led Zimmerman to kill Martin, prosecutors insisted that race had nothing to do with it.

State Attorney Angela Corey would later say, “This case has never been about race … We believe this case all along was about boundaries, and George Zimmerman exceeded those boundaries.”

Indeed, the prosecution ran from race. They refused to address how racial prejudice, which remains pervasive in American society, framed Zimmerman’s thoughts and behavior. In fact, they pretended as though race and racism did not exist.

Theirs was a colorblind prosecution that proved terribly misguided.

At the same time, prosecutors did next to nothing to disabuse jurors of their preconceived notions of young black men as dangerous. They failed to humanize Martin, to call to the stand people other than his most immediate family and friends to show that he was no different than the young people in the jurors’ own lives.

African Americans know this intuitively, but this remains a stretch for other Americans whose primary image of black males is what they see during the crime segment on the local news.

Unlike the prosecution, Zimmerman’s attorneys did not shy away from race. They played to prevailing racial stereotypes of black men as criminals to explain away Zimmerman’s mistaken assumption that Martin was a burglar.

Once black criminality was established, not a difficult task given prevailing assumptions about blacks and crime, Zimmerman’s profiling of Martin seemed logical. It became something the jurors themselves might have done in the same situation.

The defense attorneys did not stop there. They continued to play to racial prejudice by portraying Martin as dangerous. It did not matter that Martin was unarmed or that he did not initiate the encounter. As a black male, he was a threat. Martin’s race lent credibility to Zimmerman’s claim that the young man was going to kill him. Indeed, it was the pivot around which Zimmerman’s self-defense claim turned.

In the end, race trumped reality.

It is clear from post-trial interviews with jurors that they never connected with Martin on a personal level. He remained to them a menacing racial other. Instead, they identified with Zimmerman. They related to his story of being afraid of a young black male and accepted his actions based on this manufactured fear.

“We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest”

The weight of painful history continues to fuel the desire of many African Americans to keep fighting for justice for Trayvon and to end the kind of racial prejudice that led to his death and Zimmerman’s acquittal.

“We stand with Trayvon’s family and we are called to act,” declared Benjamin Todd Jealous, the president of the NAACP, the nation’s leading civil rights organization. “We will pursue civil rights charges with the Department of Justice, we will continue to fight for the removal of Stand Your Ground laws in every state, and we will not rest until racial profiling in all its forms is outlawed.”

More than 1.5 million people have signed the NAACP’s petition to the Justice Department asking that federal charges, including civil rights charges, be filed against George Zimmerman.

In the Age of Obama, there has been a great deal of debate about America being a post-racial society. The killing of Trayvon Martin and the failure of the legal system to provide a modicum of justice ought to put this debate to rest.

America is not a post-racial society; far from it. Indeed, white Americans, including the most well-meaning white Americans, need to stop pretending to be colorblind. They need to acknowledge the ways that race, personal prejudice, and institutionalized racism impact and inform our daily lives.

During the civil rights era, the singing group Sweet Honey in the Rock lamented that the killing of black men—black mothers’ sons—is not as important as the killing of white men—white mothers’ sons.

Some fifty years later, this sad fact of American life remains true. It is also true, as the singers declared, that until such time as this is no longer the case, “we who believe in freedom cannot rest.”

Books

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010).

David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2001).

Kevin Boyle, Arc of Justice: A Sage of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age (2004).

Taylor Branch, At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68 (2006).

Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (2005).

David M. P. Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (2007).

Tom Jackson, From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Struggle for Economic Justice (2007).

Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth Century America (2005).

Blair L. M. Kelley, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy V. Ferguson (2010).

Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (2005).

Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (1998).

Khalil Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, And The Making Of Modern Urban America (2010).

Thomas J. Sugrue, Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (1996).

Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (2008).

Craig Steven Wilder, A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn (2000).

Film, Documentaries, and Television

Slavery By Another Name, Dir. Samuel D. Pollard (2012).

Revolution ’67, Dir. Marylou Tibaldo-Bongiorno and Jerome Bongiorno (2007).

The Central Park Five, Prod. Ken Burns, David McMahon, Sarah Burns, Antron McCray, and Raymond Santana (2013).

Fruitvale Station, Dir. Ryan Coogler (2013).

Homicide: Life on the Street, Creator Paul Attanasio (1993-1999).

The Wire, Creator David Simon (2002-2008).