Welcome aboard the train, British History! In preparation for our adventure through the twentieth century, please refer to the guidebook prepared for each passenger, Tim Bryars and Tom Harper’s A History of the Twentieth Century in 100 Maps. This visually-stunning book is an excellent aid to the whirlwind ride you are about to take. Most of these maps have never been reprinted since their first publications. They illuminate how the British viewed the world and, conversely, how the rest of the world viewed Britain (p.8).

As we embark, please pardon the beginning snail-like pace—this preeminent global empire is pulling colonized freight cars from almost every continent in the world. The bloody 1900 Boer War and increased competition with the Germans over railroad and maritime control have also worn down this locomotive. Still, this “weary titan” (p.15) is in tip-top condition and bravely chugging into World War One. The taste of victory is especially sweet, considering the magnitude and intricacy of the network connecting the German trenches together (as mapped out on p.56-7).

Although the train has emerged from the Great War as the undisputed “top dog” of the world (p.60), the next portion of this expedition will regrettably be very jerky. From the massacre at Amritser in 1919 to the nine-day massive nation-wide strike (1.5 million workers from all industries) of May 1926 to the world financial crash in the 1930s, passengers may be thrown from their seats as these crises unfold. There will be intermittent periods of smooth-sailing, where you can stroll through the Hundred Acre Wood, or witness the royal coronation of George VI in 1937. Nonetheless, please remain seated otherwise, specifically when the train teeters near the cliff-edge of World War Two and shakes violently from the bombings (maps are provided to enlighten the readers of the damage outside). Rest assured, however, that Britain will pull through!

Indeed, the end of the war ushers in slightly over twenty years of “boom” economy and expansion (p.117). Despite the chaos created by the ongoing conflict between our alliance railway, the United States, and our nemesis, the Soviet Union, this train continues its ascent to the peak of technological development and urban industrial regeneration. If they so desire, travelers can alight at the recreational stations situated along the way to explore J.R. R. Tolkein’s Middle Earth, engage in some football (the English, not American kind), and even tour Hong Kong, the Pearl of the Orient that belonged to Britain until 1997.

Unfortunately, the voyage takes a sharp nosedive from here on out, signaled by the 1972 Bloody Sunday and the 1973-4 OPEC Oil Embargo. Passengers who peer out will delight in the frenzied production of consumer goods in the form of fast food restaurants, videogames, and Disney World. However, those who look closer will notice that the consumers’ society is built upon a landscape ravaged by global capitalist inequality, AIDS, nuclear debates, and war; and the Conservative Party that was in power from 1979 to 1997 has done nothing to curb this excessive wealth and power disparity. As a result, these problems continue to plague Britain and the world.

We hope passengers appreciate the efforts put forth by the cartographers to amass such a wide variety of maps, and situate them all within their proper historical context. True, their analyses are rather uneven; maps utilizing zoomorphic imagery are superbly interrogated, while gender and race are treated too superficially. A few maps also seem out of place, such as the spy map for Japanese submarines at Pearl Harbor (p.98-9), an important map for sure but one that the cartographers do a lackluster job of tying back to this ride through the British twentieth century.

The greatest omission, however, is their abrupt treatment of the disintegration of the British Empire. Passengers by now may have realized that the train has picked up speed since most colonies have gained independence, and broken off to form their own railways. Alas, those who flip through the book will notice that Bryars and Harper only briefly discuss the decolonization of India, Pakistan, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Palestine/ Israel, and completely ignore the rest of Africa and Southeast Asia. The book is surprisingly silent even on the 1989 collapse of the South African apartheid regime. Furthermore, Britain is portrayed as a benign bestower of independence, a portrayal akin to a slap in the face for those who grew up in the former colonies (such as the author of this review).

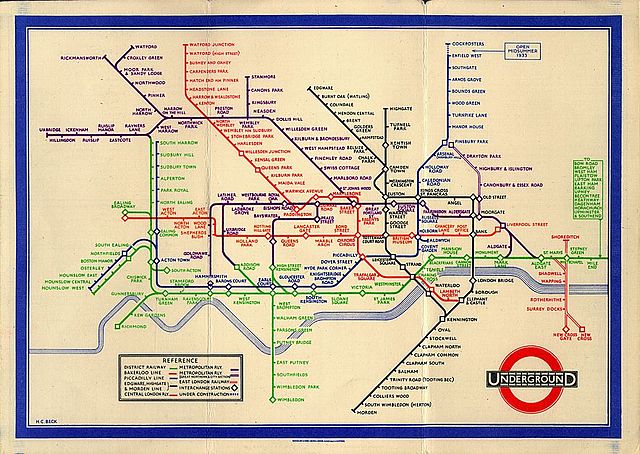

This is such a pity for a proper treatment about decolonization could have illuminated the complex relationship that Britain had, and continues to have, with her former colonies. Case in point: Harry Beck’s 1933 schematic diagram of the London Underground Railway system (p.9) revolutionized train mapping because it favored clarity and simplicity over geographic accuracy. (It is puzzling that Bryars and Harper acknowledged its historic significance in the introduction but excluded it from their collection of a hundred maps.)

|

| Harry Beck’s London Underground Railway map, designed in 1931 and released to the public in 1933. |

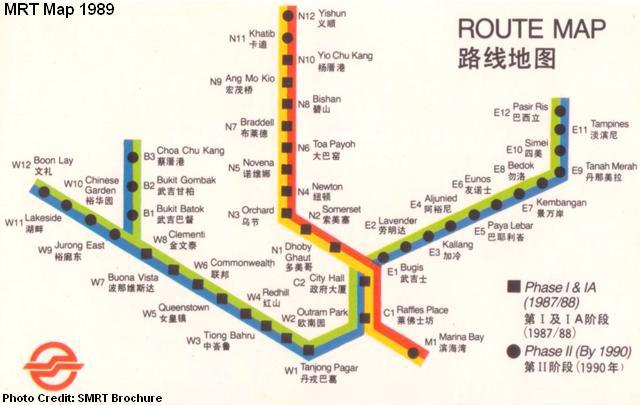

Beck’s map inspired a new generation of diagrammatic subway maps, including those in its former colony, Singapore. When Singapore’s own train system, the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), began running in 1987, the map adopted the same principles used by Beck.

|

| Map of Singapore’s MRT system, 1989 |

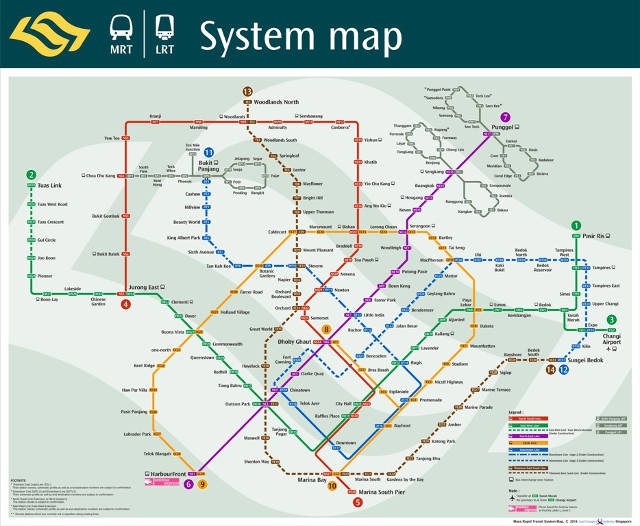

In fact, the similarities to Beck’s diagram only increased as time went on, not to mention that many stations retained their British-influenced names:

|

| Map of Singapore’s MRT system, 2014 |

Maps could have been an effective tool to discuss decolonization, but the book disappoints in this aspect. Be that as it may, it remains an impressive guide to navigating the turbulent terrain of twentieth century British history, as long readers understand that maps can only supplement, not supplant, historical learning.

With that note, we have reached the end of the journey. Please feel free to keep the book as a token reminder of the trip. Just as Bryars and Harper have highlighted how maps serve a dual purpose of practical and emotional documentation (p.228), we hope this book will remind you of the events and emotions of this voyage through the twentieth century. Thank you for riding the British History, and we hope to see you again!