The shift in public opinion in favor of gay rights, exemplified by the legalization of gay marriage, has been a defining feature of life in the United States over the past decade. Despite such gains, opposition to gay rights, exemplified by government officials like Kim Davis, remind us that considerable disagreement still exists over this issue. Davis’s refusal to issue marriage licenses to gay couples represents an example of the often complex relationship between government officials and broader social, cultural and political trends. In his book Hoover’s War on Gays: Exposing the FBI’s “Sex Deviates” Program, Douglas M. Charles further investigates the juncture of government officials and society at large.

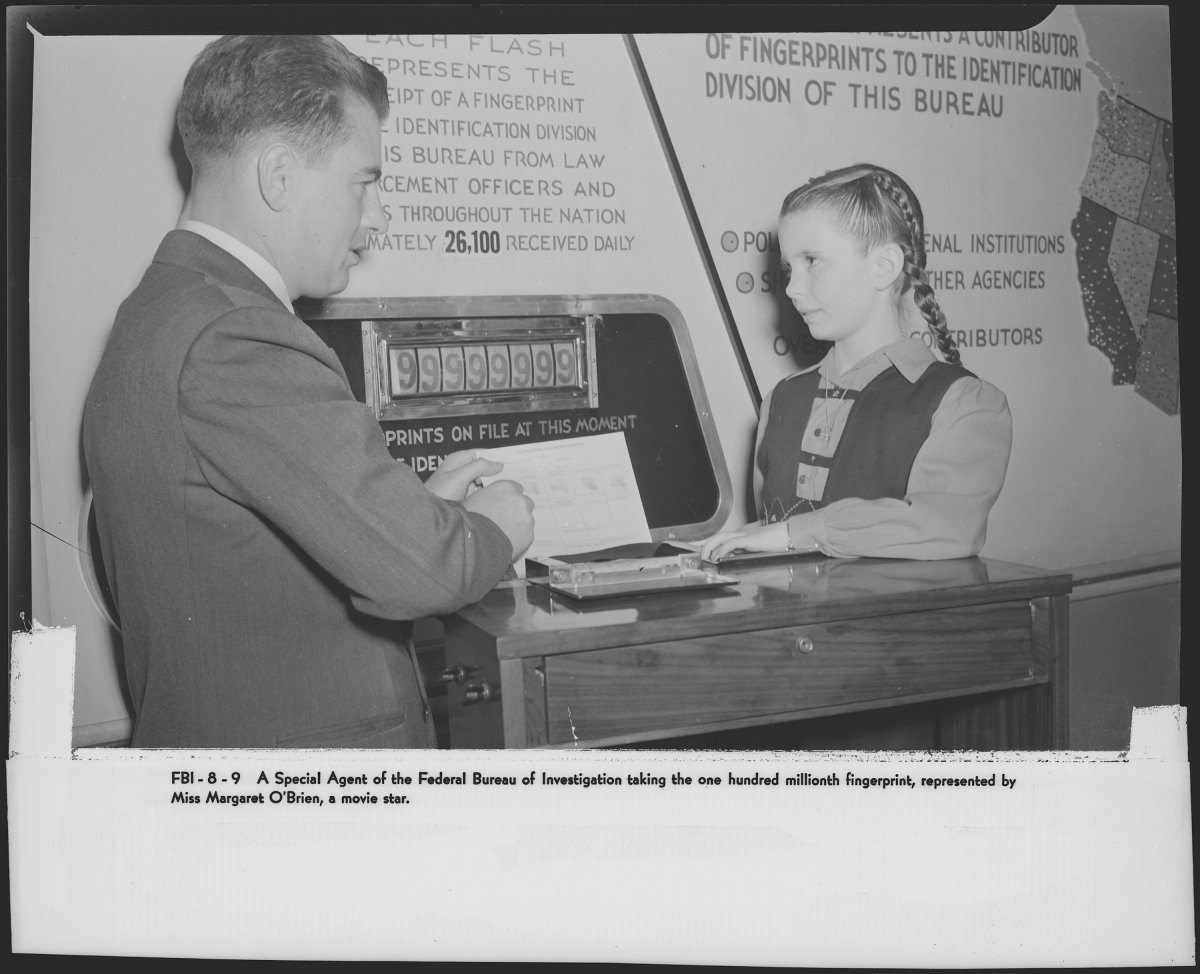

As Charles notes in his book, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was viewed with fear and apprehension by gays and lesbians for much of the twentieth century. With connections, abundant resources and “a carefully crafted public image as scientific investigators,” FBI agents had the potential to ruin the lives of gays and lesbians who fell afoul of the Bureau by investigating and outing them (p. xi). Building on his other books about the Bureau, Charles seeks to write the first comprehensive history of the FBI’s policies and actions towards gay Americans during the twentieth century, with a specific focus from the years between the 1930s and the 1990s.

Charles argues that, while an underlying animus consistently undergirded FBI policies toward gays, the Bureau’s “interest in homosexuality was an evolutionary phenomenon” (35). No single factor, event or personality neatly explains FBI actions during these years. Rather, Charles maintains that the FBI regularly responded to changes in the social construction of homophobia, which “was/is something influenced by shifts in US society and culture” (xv). Hoover’s War on Gays is thus devoted to connecting changes in FBI policies and actions toward gay Americans to larger social, cultural and political trends. He also, however, takes great pains to understand how the FBI had an impact on gay rights organizations and a whole range of individuals, including gay rights activists, federal civil servants and politicians.

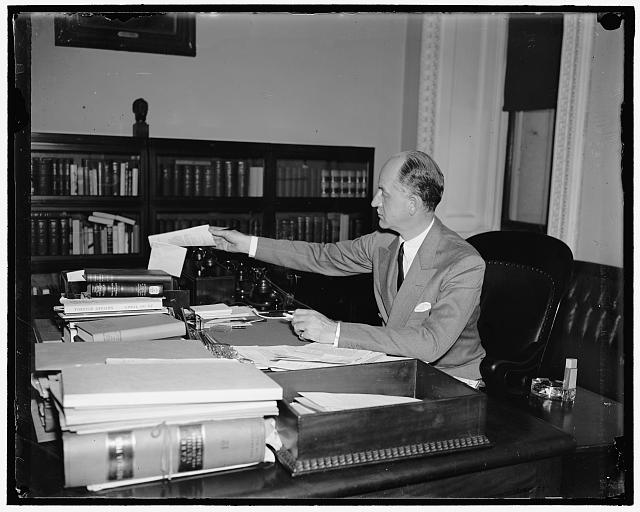

|

| FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was one of the primary drivers of the Bureau’s crusade against gays in government. |

More often than not, Charles capably accomplishes his task of tying FBI actions and policies to prevailing social, political and cultural trends within the United States. His exploration of the origins of the “Lavender Scare,” for instance, is both insightful and convincing. The Lavender Scare was a period of intense persecution of suspected gays in government service in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Charles makes the obvious connection between the purging of gays, who were thought to be susceptible to blackmail, from government jobs and early Cold War-induced paranoia about possible security breaches.

He goes a step further, however, in discussing the conflation of homosexuality and communism as subversive forces in US society. Anticommunists, Charles notes, defined communist subversion “in terms of weakness, effeminacy, or softness” and such rhetoric echoed “the perception of gays in the United States of the 1950s…as a threat to manliness in hypermasculinzed, patriarchal US culture” (75). He further drives home how, to the public, both gays and communists were nonconformists on the margins of US society. Gays and communists “kept their true identities hidden, both seemed to move around in a secretive underworld, both had a common sense of loyalty, and both had their own publications and places to meet” (97). Unlike some politicians who openly embraced the public conflation of gays and communists, the FBI was careful to treat them as distinct threats. Such distinctions did not, however, limit the Bureau’s involvement in the Lavender Scare. Tasked with limiting the potential for subversion, the FBI played an instrumental role in targeting and purging alleged homosexuals from government service.

While Charles successfully connects the actions of the FBI to greater cultural, social and political trends, at times his efforts to understand their impact on individuals becomes a tad repetitive. For example, Charles’s third chapter contains three case studies about prominent gay, or allegedly gay, individuals to highlight how security concerns about gays in government emerged during World War II. One of these case studies centers on Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles, a homosexual who was a friend and confidant of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Welles was investigated discretely and to an extent tolerated because Hoover was a holdover from a Republican administration who “was careful to do everything at his disposal for the president to ensure his continued tenure as FBI director” (39). When Welles failed to behave to Hoover’s satisfaction, however, Hoover quietly facilitated efforts that raised the political costs of protecting Welles to the point where Roosevelt cut his losses and fired his friend.

|

| Welles, who served as Undersecretary of State from 1937 until 1943, was one of FDR’s closest advisers on foreign affairs until he was pressured into resigning due to his sexuality. |

Through this focus on Welles, Charles ably demonstrates how bureaucratic considerations, like Hoover’s standing with the president, and political considerations, like the potential fallout of a prominent official being openly identified as gay, factored into the Bureau’s actions. In his seventh chapter, Charles draws essentially the same conclusions from his discussion of the 1964 arrest of Walter Jenkins, an aide to Lyndon Johnson, for having sex with another man. As insightful as those conclusions are, and as capably as Charles conveys them, they do not necessarily need to be repeated again.

Such relatively minor quibbles do not, however, detract from the overall quality of Hoover’s War on Gays. Charles has written a well-researched, highly readable and ultimately compelling book about how the FBI’s policies and actions towards gays have been influenced by a variety of personalities, events and different social, cultural and political forces. The implications of his work are interesting. The FBI does not, in Charles’s telling, exist in a vacuum. Rather, the Bureau and its priorities are consistently shaped by outside forces that are largely attuned to the attitudes of the public at large. FBI surveillance and harassment of gays for much of the twentieth century in response to widespread homophobia highlights the most problematic aspect of that responsiveness. The existence of such responsiveness, however, inspires hope. If public attitudes provide strong incentives for not just the FBI, but government at large to operate in limited contours and if public attitudes are as malleable as the changing tide on gay rights suggests, then ultimate authority resides precisely where it is supposed to: with the people.