Scandals involving performance enhancing drugs have repeatedly rocked the sporting world. Governing bodies of sport at the highest levels now work aggressively to prevent the use of banned substances and to test and catch those who have used them. This month, Ian Ritchie reminds us that doping to improve performance has been around for more than a century. It is only recently that sports leaders have become determined to ban certain substances, a shift that coincided with the end of the Olympic amateur ideal.

Read these insightful Origins articles on Olympic Controversies Past and Present; The Soccer World Cup in South Africa; Russia and the Sochi Olympics; The World Series; and Rome and Athens in American Sports Culture

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on The Politics of International Sport; The Future of the NCAA; Taylor Branch on the Crisis of College Sports

Doping scandals have been shaking the world of sport for almost a half century. However, the recent scandal provoked by the announcement from the three-man panel at the press conference in Geneva, Switzerland on November 9, 2015 seemed different.

Flanked by Canadian lawyer Richard McLaren and German police investigator Günter Younger, Canadian lawyer and former head of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Dick Pound presented “The Independent Commission Report #1” to the press corps. The 323-page report revealed widespread doping and a “deeply rooted culture of cheating” in Russian athletics and in the country’s anti-doping establishment.

Pound listed off charge after charge of corruption including financial payoffs to conceal positive doping results, the destruction of samples in a corrupt Moscow testing lab, and coaches and administrators who demanded athletes dope to enhance their performance.

Among the 42 recommendations specific to Russian sport and anti-doping, the most serious included that the entire Russian athletic federation be suspended from international competition – including, potentially, the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, and that five coaches and another five athletes, including 2012 Olympic gold medalist Mariya Savinova (below), be banned for life.

Finally, the report moved beyond Russia also to recommend serious action against the International Association of Athletics Federations, which oversees track and field competitions worldwide. Holding back specifics because of ongoing police investigations, the report followed arrests in France only one week earlier.

By most accounts, the Independent Commission’s report was a game changer in international sport. No report before it had revealed corruption so systematic and widespread.

But was the “Russian doping scandal” really such a big moment in the history of anti-doping?

After all, as even casual observers of doping scandals over the years will acknowledge, “game changing” scandals have come and gone, yet the common practice of using performance enhancing substances has remained more or less consistent, even as anti-doping efforts have become better coordinated.

|

Sports authorities often use the analogy of “cops and robbers” in reference to athletes who cheat by using performance enhancing substances. They—most importantly those of WADA, which has overseen global anti-doping efforts since 1999—see themselves constantly chasing those athletes and trying to keep up the technological “race” to test athletes who are supposedly taking increasingly sophisticated substances.

But that analogy oversimplifies the situation, especially if we look at the changing nature of doping rules and regulations rather than at the substances themselves. Doping was not always considered unethical and it took several generations for the ethics to change.

If one really wants to pinpoint the watershed moment in the world of anti-doping and sport it was 1967. It was in that year that the highest level of sport administration—the International Olympic Committee (IOC)—banned certain performance enhancing substances.

As the sports community increasingly challenged and abandoned the cherished Olympic ideal of “amateurism” during the cold war, the IOC turned instead to anti-doping as the moral bedrock that would maintain the ethos of pure sport. But maintaining the virtue of sport on these terms has proven a tremendous challenge to sports leaders everywhere.

From Curiosity to Controversy

There is good evidence that some athletes during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used a variety of substances as “one off” solutions in competition—the use of a certain substance or method to enhance performance on the day of the event.

Alcohol, strychnine, coca, kola, tobacco, ultraviolet rays, purified oxygen, and other equally exotic substances were used, mainly before or during endurance events such as long distance running, pedestrian walking, and cycling. Such usage was common in these sports that often attracted large spectator crowds.

Asking whether these substances enhanced athletic performance misses the point. Athletes, their coaches, and other handlers believed they worked and used them because they intended to enhance performance. Thus they should be considered historical examples of “doping.”

One interesting thing about the turn of the century is that athletes, coaches, and many sports fans alike maintained an open mind, even a spirit of curiosity about what effects the substances might have on athletes’ bodies.

Certainly there were those who disagreed, and at times voiced their concerns publicly, but often those voices were based on religious temperance and concerns with social vices in general – drinking, gambling, and “unruly” social behavior.

The first scientific experiments on the effects of substances on performance and fatigue were conducted in a spirit of curiosity. In fact, biomedical science and athletes’ curiosities about what could make them go faster for longer fed one another.

|

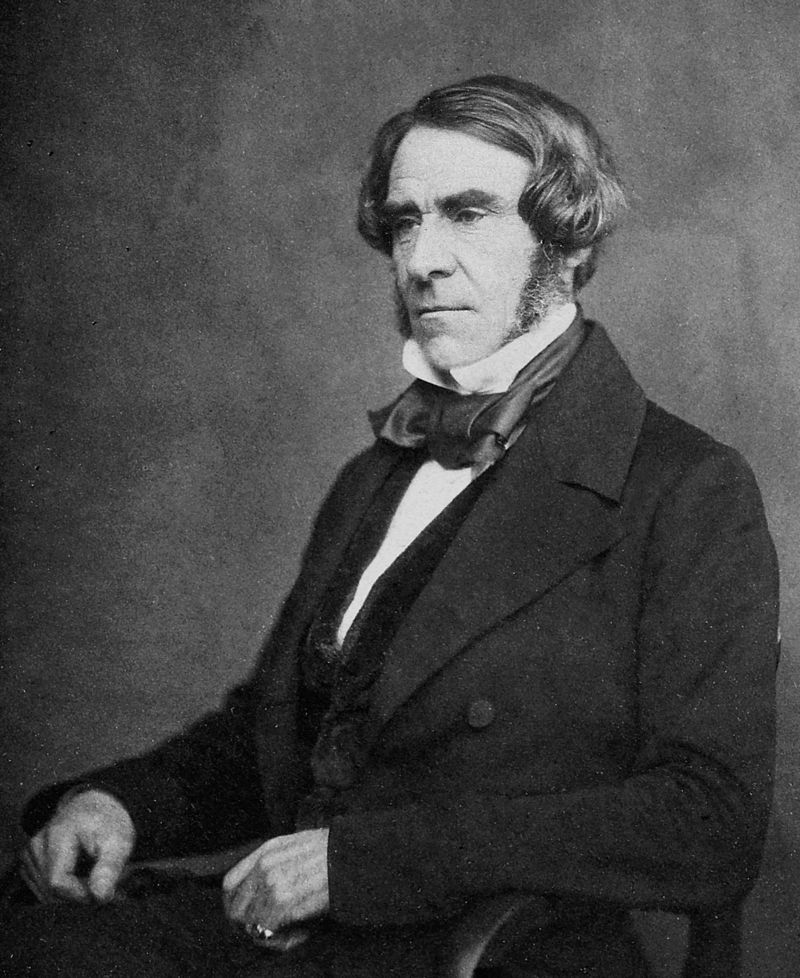

In one of the first systematic series of experiments on human endurance, respected physician Sir Robert Christison, professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh and president of the British Medical Association, set out in the 1870s to test the “restorative and preservative virtues” of Peruvian coca-leaf extracts by performing experiments on both himself and students. His tests revealed positive results during extremely long bouts of walking and he subsequently published his findings in the British Medical Journal in 1876.

While results of Christison’s experiments and similar ones had not previously been available for common readers, they were covered in a number of popular science and medical journals in the late nineteenth century. Some athletes participating in long distance events read them and experimented in turn.

In this environment of curiosity and experimentation, creating rules against the use of “dope” was seen as unnecessary in human sporting competition.

In fact, it was in horse racing that the first doping rules were created, though ironically the rules were designed to prevent trainers from impairing the performance of their horses. Slowing horses down made it easier to fix a race.

Amateurs, Professionals, and Anti-Doping

In human competition, the condemnation of substance use emerged slowly in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

As national and international sport organizations vied for attention and power in the 1920s and 1930s—the decades sport truly became “international”—they battled over what “true” sport meant.

Far and away the most important dispute in the “sport wars” of the times was between those who defended amateur sport and the “true sportsmanlike behavior” embodied by amateur athletes, and profit-driven owners benefitting from the growing tide of professionalism and the athletes who felt they could make a few bucks—or even potentially a living—from sport.

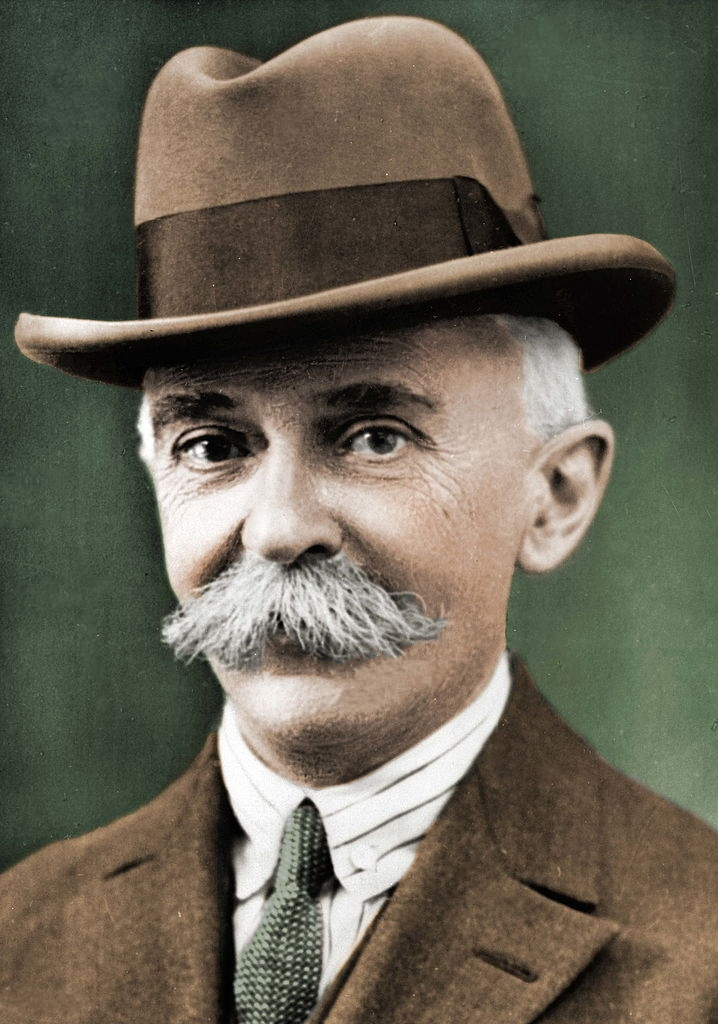

The Olympic movement had quickly become the main ambassador for amateur values. Much of that is owed to the Games’ founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin (right), although the ideals Coubertin envisioned for the Games were far more complex than those represented by amateurism and the practices of the elite public school system in England, from which amateurism found much of its inspiration.

The Olympic movement had quickly become the main ambassador for amateur values. Much of that is owed to the Games’ founder Baron Pierre de Coubertin (right), although the ideals Coubertin envisioned for the Games were far more complex than those represented by amateurism and the practices of the elite public school system in England, from which amateurism found much of its inspiration.

Coubertin expected athletes to be morally upstanding role models. Drawing on ideals from literature about medieval chivalry, he believed athletes should embody “a knighthood. … ‘brothers in arms,’ brave, energetic men united by a bond that is stronger than that of mere camaraderie.”

Of course, stating such lofty ideals and following through on them in the actual sporting practices of the Games themselves were two entirely different things.

In the Olympic Charter, amateurism was not formally defined until 1930. Athletes who participated in the Games, that version stated, “Must not be … a professional in the Sport for which he is entered or any other sport” and “Must not have received re-imbursement or compensation for loss of salary.”

With rumors spreading that some athletes were using certain substances to gain advantage, the amateur/professional divide determined whether or not athletes were criticized. The class position of athletes and administrators played a crucial role in determining the line between “clean” versus “doped.” Criticisms of working class athletes—almost all of which were excluded from amateur sport—were few, but amateurs, it was thought, represented true “sportsmanship” and therefore had to be clean.

This class divide can be seen in two important cases of athletes who competed in the early days of the Olympic marathon event. Even by the turn of the century, marathon running was considered a borderline amateur/professional case; it played a central role in the Olympic Games but prize money was regularly awarded in other events.

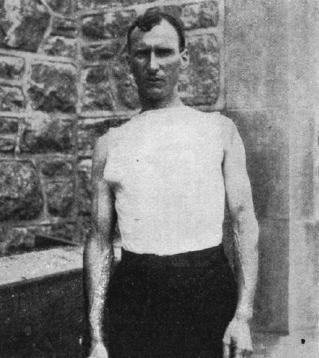

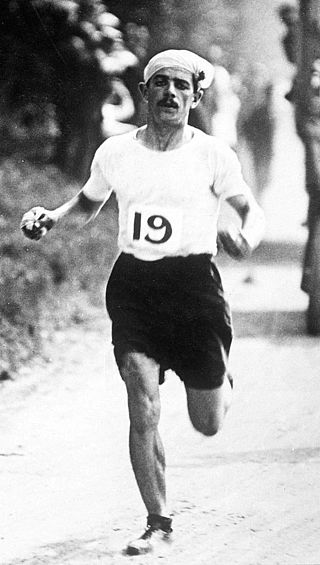

Runners Thomas Hicks (below left) and Dorando Pietri (below right) won the 1904 and 1908 Olympic marathons respectively. While officials knew that both of them ingested strychnine along with other substances, both runners received little moral condemnation because the sport itself teetered between amateur and professional.

|

|

But by the 1920s and 1930s, with the doping issue raising its head and the IOC and its affiliate organizations increasingly defending the purity of amateur sport, the first serious discussions of the morality of drugs emerged. The International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), which oversaw track and field, was the first major organization to condemn drug use as “cheating.”

In 1928, the group unanimously adopted a rule against “stimulants,” publishing the first major rule against drugs in human sport in its Handbook. The restriction stated that “Doping is the use of any stimulant employed to increase the power of action in athletic competition above the average” and that breaking the rule could lead to suspension “from participation in amateur athletics.”

By the 1930s, the IOC had become the most powerful sport organization in the world and had taken a stronger stand on amateurism.

Two controversies in that decade heightened concerns about the degree to which athletes were willing to push the limits of performance enhancement, especially the use of state resources to improve performance and potentially the use of “dope” in order to help them push those limits further still.

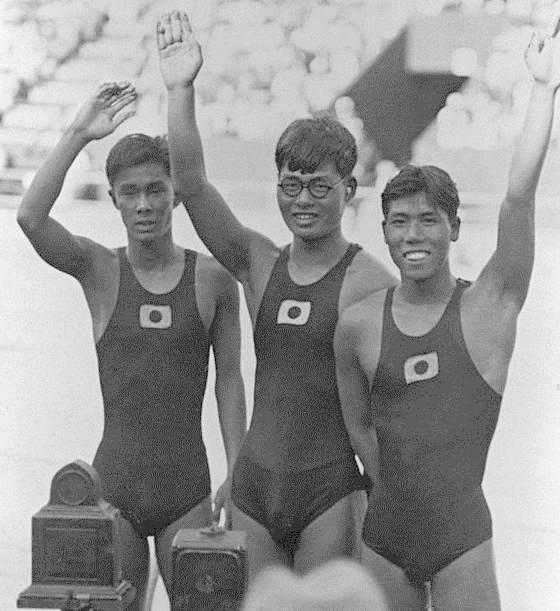

First, American authorities accused Japanese swimmers of using “purified oxygen” during the 1932 Summer Games in Los Angeles. Even if the accusations were based more on nationalistic fervor on the part of the Americans than actual proof of the practice, IOC members took notice and the accusations and hearsay received widespread press.

|

Second, IOC members were fully aware of rumors and accusations during and following the 1936 Games in Berlin that the National Socialists provided state financial and bureaucratic resources to improve their chances of winning the most medals—which they did—in direct conflict with amateur principles. The German case leading up to the Berlin Games was not one of doping, per se, but reflected the seriousness of the IOC’s concern about any activities that would enhance athlete performance and contradict the spirit of amateurism.

|

In the wake of these episodes, the IOC launched an investigation. IOC Vice-President Henri de Baillet-Latour announced in a letter that “amateur sport is meant to improve the soul and the body [and] therefore no stone must be left unturned as long as the use of doping has not been stamped out.” In the same letter he also made the exaggerated claim that “[d]oping … likely implies an early death.”

Before the commission meeting in Cairo in 1938, American member Avery Brundage (who would take over as President from 1952 to 1972) wrote, “[t]he use of drugs or artificial stimulants of any kind cannot be too strongly denounced and anyone receiving or administering dope or artificial stimulants should be excluded from participation in sport of the O.G. [Olympic Games].”

|

|

IOC President Henri de Baillet-Latour (left) in 1936, under whose direction the first statements against dope were made in the 1930s. Avery Brundage (right, pictured here in 1964), IOC member before WWII and later President (1952), whose strong amateur beliefs played a role in the creation of anti-doping rules.

While bureaucratic activities were interrupted by World War II, in 1946 the Olympic Charter included the statement (under the heading “Resolutions Regarding the Amateur Status”) that “doping” was a subset of amateur principles. That position would remain in the Charter until 1975, one year after the IOC abandoned the formal amateur principle in its Charter.

The Postwar Fight Intensifies: Keeping the Flag of Idealism Flying

The use of drugs in athletics grew dramatically after World War II. The first two decades after World War II witnessed increasing use of drugs to enhance performance, the employment of new drugs, increasing scientific sophistication, and in some cases the aid of state and private actors to help athletes.

While most applications before WWII had been “one offs” – substances taken just before or during events, in particular amphetamines or derivatives that enhanced energy – in the postwar years drugs employed on a day-to-day basis as part of athletes’ training regimes became more common.

|

The use of “pep pills” to create energy or fight fatigue was still common and generally accepted in sport.

But the story of performance enhancement in sport changed with the development of anabolic steroids. Steroids were not just new drugs, they were drugs administered systematically and this was part of the reason that they were so strongly condemned at the top levels of sport.

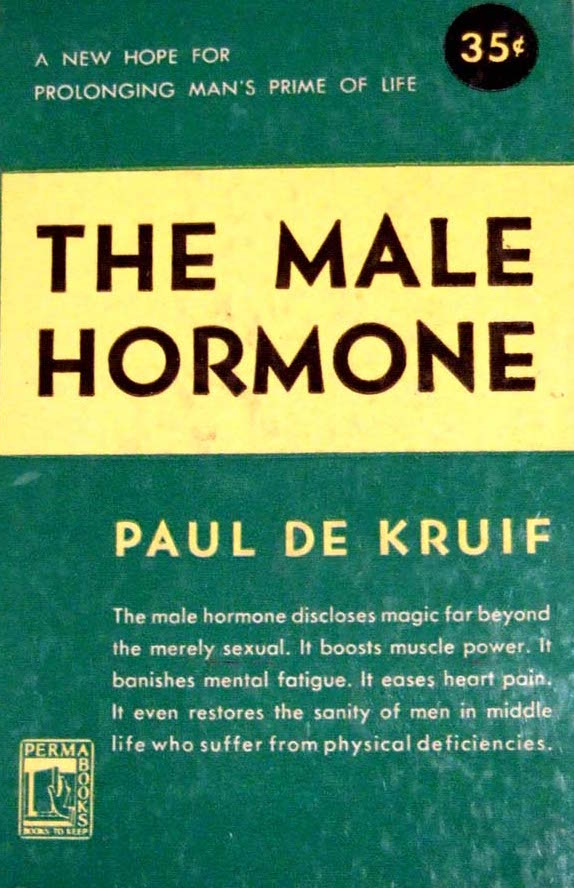

Even though anabolic steroids had only been synthesized in the 1930s, by the late 1940s and then into the 1950s there was a rising interest in the drug’s potential to strengthen and rejuvenate the body. In the United States, for example, Paul de Kruif’s top-selling 1945 publication The Male Hormone strongly defended the ability of steroids to enhance energy, build strength, combat fatigue, and even to extend lifespan.

At the highest levels of Olympic sport, drug use intersected the dynamics of the cold war.

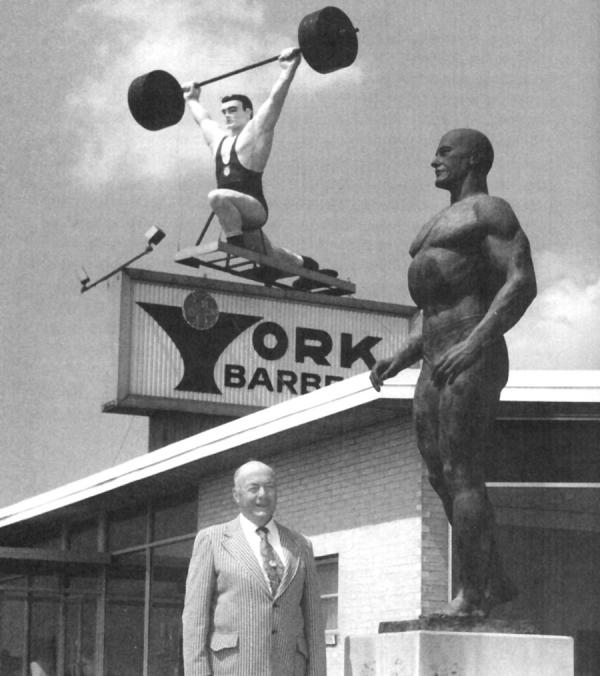

After the 1954 World Weightlifting Championships, American coach Bob Hoffman and the team’s physician John Ziegler were convinced that Soviet weightlifters were gaining an advantage from steroid use. With the aid of the Ciba Pharmaceutical Company, which produced the synthetic steroid methandieone (Dianabol), Ziegler gave the drug to weightlifters at the York Barbell Club in Pennsylvania.

|

From there, the use of anabolic steroids became more common in weightlifting circles but also spread to various track and field events including shot putting, hammer throwing, discus, and several other strength-related events.

Avery Brundage, whose original hand-written note was still in the Olympic Charter as a subset of amateur restrictions, served as President of the IOC during the heady cold war years. Wanting to preserve the principles of amateurism but recognizing at the same time that the cold war was pushing athletes’ training regimes to unthinkable levels of professional-like commitment, the IOC attempted to push Olympic sport back to the amateurism its founder Coubertin envisioned.

“Sport, which still keeps the flag of idealism flying,” Brundage wrote, “is perhaps the most saving grace in the world at the moment, with its spirit of rules kept, and regard for the adversary, whether the fight is going for or against.”

The IOC went so far as to attempt to create rules against excessive training regimes, including the restriction of numbers of hours per day or week to train, but to no avail. The use of performance enhancing drugs, however, was a different thing.

Brundage was understandably concerned over a crisis in cycling during the 1960 Rome Summer Games. Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen collapsed riding his bike during the road race and subsequently died. Amphetamines were assumed to play a role in his death, and thus anti-doping took center stage on the IOC’s policy agenda.

|

Fifteen days after Jensen’s death, Brundage and the IOC Executive Board met and in 1962 Brundage organized a doping subcommittee to be directed by the head of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Sir Arthur Porritt.

The subcommittee summarized its conclusions in the IOC’s Bulletin in 1963. It defined doping as “an illegal procedure used by certain athletes, in the form of drugs; physical means and exceptional measures which are used by small groups in a sporting community in order to alter positively or negatively the physical or physiological capacity of a living creature, man or animal in competitive sport.”

As a definition of doping, the statement was fraught with problems because certainly many of the doping practices of athletes were not illegal, and “exceptional measures” was extremely vague. But the statement did reflect the fear of just how far beyond the restrictions assumed within amateur principles athletes were now willing to go.

Then, after meetings in Tokyo and Tehran, the IOC in 1967 formally defined doping as “the use of substances or techniques in any form or quantity alien or unnatural to the body with the exclusive aim of obtaining an artificial or unfair increase of performance in competition.”

The Mexico City Summer Games in 1968 were the first held after this new definition of doping. There, limited random tests were conducted on athletes, and while a test for anabolic steroids did not yet exist, those tests were developed in 1973 and testing for steroids was first implemented at the Montreal Summer Games in 1976.

Anti-Doping Post-1967: Ethics Passé and Morally Dulled Individuals?

The 1967 rulings by the IOC effectively ushered in the modern era of drug testing and cheating. With the 1967 rules in place, authorities throughout the 1970s and 1980s set their attention to the more mundane tasks of coordinating testing procedures, advancing the technology for testing, and seeking compliance in international bodies participating in Olympic sport.

With enhanced testing throughout the 1970s and 1980s, alongside a series of scandals that highlighted the issue to the general public, the “cops and robbers” analogies began and only became more common as media accounts vividly described—and embellished—the dangers of drug use and a world of “cheating” in sport spinning out of control.

Almost immediately after the 1967 rules were created, the media discovered the issue. In 1969, for example, Sports Illustrated ran a cover-story titled “Drugs: A Threat to Sport,” and illustrated it with a splayed-out silhouette of an athlete, surrounded by six groups of pills labelled “muscle relaxers,” “painkillers,” “anabolic steroids,” “amphetamines,” “barbiturates,” and “tranquilizers.” A large hypodermic needle is angled toward the silhouette with the sharp end pointed into the athlete’s body.

|

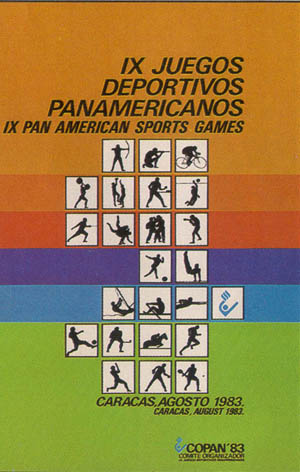

1969 Sports Illustrated cover “Drugs: A Threat to Sport” with various sport-doping drug types (left). Poster from the 1983 Pan American Games (Caracas) where surprise tests for steroids were conducted and several athletes were caught (right).

Doping scandals have flourished regularly since 1967. The first major of these occurred at the Pan American Games in Caracas in 1983, when advanced testing procedures produced 19 positive tests and caused several athletes to fake injuries or to create other excuses for leaving the Games in fear of being caught.

In 1988, Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson, then the fastest man in the world, tested positive at the Seoul Summer Olympic Games, leading to a major Canadian government inquiry that reshaped anti-doping in that country and eventually influenced sport policies at the highest levels, including current WADA policies.

In 1998, international attention also focused on the Tour de France after customs officials and police discovered hundreds of doses of endurance-enhancement drug erythropoietin (EPO) in vehicles belonging to the TVM and Festina teams. The scandal resulted in riders staging a “sit down” strike during stage 17 and the Tour itself nearly collapsed.

|

Ensuing investigations led to prosecutions, and the event played a central role in the creation of WADA in 1999. Several years later, cyclist Lance Armstrong’s career imploded spectacularly after he finally admitted to doping. Meanwhile, baseball was witnessing its own “steroid era.”

Indeed, the first lesson to be learned from the history of doping and anti-doping before 1967 is that positions on doping were mixed, and the further back in history we go, the more mixed they become. Only after 1967 has the “ethical” issue been presumed and “fixed.”

Ethics per se was never really at the heart of the anti-doping movement. A combination of moral panic alongside the defense of the original amateur value system in the Olympic movement played more prominent roles in shaping attitudes about and policies toward the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

|

Writing in Olympic Review in 1965, Sir Arthur Porritt—who had overseen the IOC subcommittee that created the first rules in the Olympic Games—proclaimed that what was at stake in the fight against doping was no less than the end of sport. But instead of couching his argument on principles, including medical ones, he attacked the character of athletes. Drug users, proclaimed Porritt, had “inferiority complexes” and all those “interested in the basic values of amateur sport” should recall that a doper is a “mentally, physically, and morally dulled individual.”

Top-level officials of sport in the 1950s and 1960s didn’t rely primarily on arguments against the use of performance enhancing substances because of health risks and that doping was contrary to the fair playing field. Instead, they sometimes took “fanatical and proselytizing” approaches (in the words of Scottish historian Paul Dimeo), attacking athletes and using quasi-religious language. The “evil” of drug use threatened sport’s sanctity, and its pure foundation at the time was premised on Olympic amateurism.

Ironically, the amateur foundation upon which those who created the first drug rules based their position was collapsing at the very moment rules and testing began. Catering to pressures to allow financial incentives to enter sport more openly and from state and private agents around the world that increasingly saw the amateur restrictions as an unnecessary burden, the IOC finally gave in.

In 1974 the IOC changed its Charter “Rule 26” to permit International Sport Federations to dictate eligibility in each respective sport. Because most Federations had much to gain from allowing increasingly professionalized athletes in their sports, the 1974 rule change effectively ushered in today’s era of fully professionalized Olympic athletes and crossed the threshold of the Olympic Movement’s central principles.

With “the amateur ideal” gone, the IOC and other sports bodies staked the legitimacy of sport on ferreting out doping.

|

The Times’ recognition of Donike, a German biochemist who drove much of anti-doping behind the scenes during the 1970s and 1980s by developing testing technology, simultaneously acknowledged that anti-doping was by the late 1980s a fully established and institutionally legitimized part of sport. Anti-doping had, in only two short decades, become a permanent fixture in the world of sport.

Drugs and the Olympic Brand

Today, the World Anti-Doping Code—WADA’s ultimate rule book on drugs in sport—proclaims that the “Fundamental Rationale” for anti-doping is the protection of “the spirit of sport.” “Anti-doping programs,” the Code states, “seek to preserve what is intrinsically valuable about sport. This intrinsic value is often referred to as ‘the spirit of sport’. It is the essence of Olympism.”

Protecting sport’s “purity” has always been a central mission of the Olympic movement. Seeing his nascent movement as much more than a sport movement, founder Pierre de Coubertin wrote in Fortnightly Review in 1908 that the Olympic Games were “something else … not to be found in any other variety of athletic competition.”

It was this “something else” that IOC members had in mind when they put restrictions on certain performance enhancing substances.

As athletes, coaches, administrators, state actors, and television and other companies that could potentially profit from the exploits of athletes moved sport forward during the Cold War era towards enhancing performances and winning medals, the IOC looked back to its past for justification to ban certain elements of performance enhancement. Performance enhancement in general could not be contained—although the IOC tried—but a relatively simple rule to ban certain drugs and other practices could preserve the purity of Olympic sport.

Today, the preservation of Olympic purity—its “spirit”—is a vital component of the Olympic brand. Ultimately what history teaches us is that the latest Russian drug scandal is not, as is often portrayed, potentially the most serious case of “cops and robbers.” It is really about the kings of sport representing a sport system that must, by definition, produce the very best athletes and performances in the world while not threatening the “purity” of sport’s “spirit.”

The battle being waged is not between individuals on the right or wrong side of sport’s “law.” The battle is over the necessity to produce the best and most lucrative performances possible while still preserving the image of sport’s purity.

What is at stake in the battle is “the spirit of sport.” That, after all, is the Olympic brand.

Beamish, Rob (2011) Steroids: A New Look at Performance-Enhancing Drugs. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Beamish, Rob and Ritchie, Ian (2006) Fastest, Highest, Strongest: A Critique of High-Performance Sport. London and New York: Routledge.

Dimeo, Paul (2007) A History of Drug Use in Sport, 1876-1976: Beyond Good and Evil. London and New York: Routledge.

Dubin, Charles L. (1990) Commission of Inquiry into the Use of Drugs and banned Practices Intended to Increase Athletic Performance. Ottawa: Canadian Government Publishing House.

Gleaves, John and Llewellyn, Matthew (2014) “Sport, Drugs and Amateurism: Tracing the Real Cultural Origins of Anti-Doping Rules in International Sport.” International Journal of the History of Sport, 31 (8), 839-853.

Hoberman, John (1992) Mortal Engines: The Science of Performance and the Dehumanization of Sport. New York: Free Press.

Houlihan, Barrie (1999) Dying to Win: Doping in Sport and the Development of Anti-Doping Policy. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Hunt, Thomas M. (2011) Drug Games: The International Olympic Committee and the Politics of Doping, 1960-2008. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

International Network of Doping Research (INDR). Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University, Department of Public Health, Section for Sport Science. http://ph.au.dk/en/about-the-department-of-public-health/sections/sektion-for-idraet/forskning/forskningsenheden-sport-og-kropskultur/international-network-of-doping-research/.

Møller, Verner (2010) The Ethics of Doping and Anti-Doping: Redeeming the Soul of Sport? London and New York: Routledge.

Ritchie, Ian (2014) “Pierre de Coubertin, Doped ‘Amateurs’ and the ‘Spirit of Sport’: The Role of Mythology in Olympic Anti-Doping Policies.” International Journal of the History of Sport, 31 (8), 820-838.

Waddington, Ivan (2000) Sport, Health and Drugs: A Critical Sociological Perspective. New York: E. & F.N. Spon.