For many months tragic stories of refugees fleeing the Middle East and parts of Africa have dominated the headlines. The fight over the Trump administration's executive orders on immigration reminds us that the refugee crisis has certainly not gone away. Nor is it new. As historian Peter Gatrell charts this month, the one hundred years between World War I and today's conflicts might well be called the century of refugees.

A great deal of ink—and much blood—has been spilled during the current “refugee crisis.” But what do we mean by that phrase?

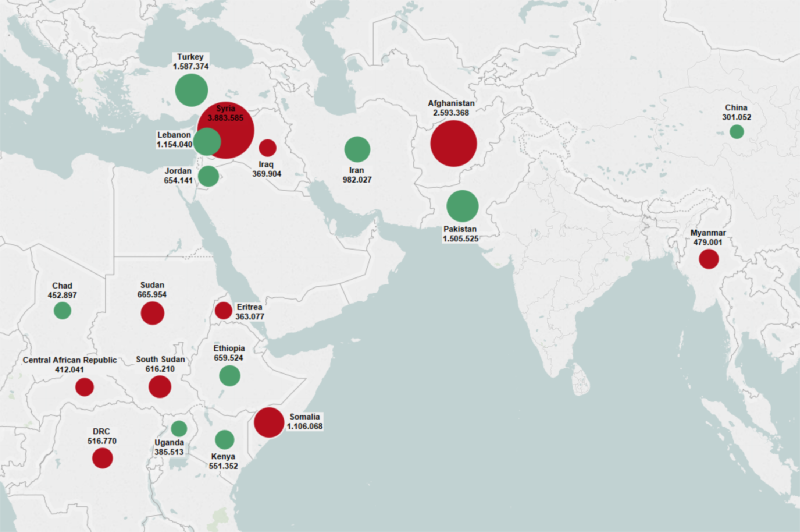

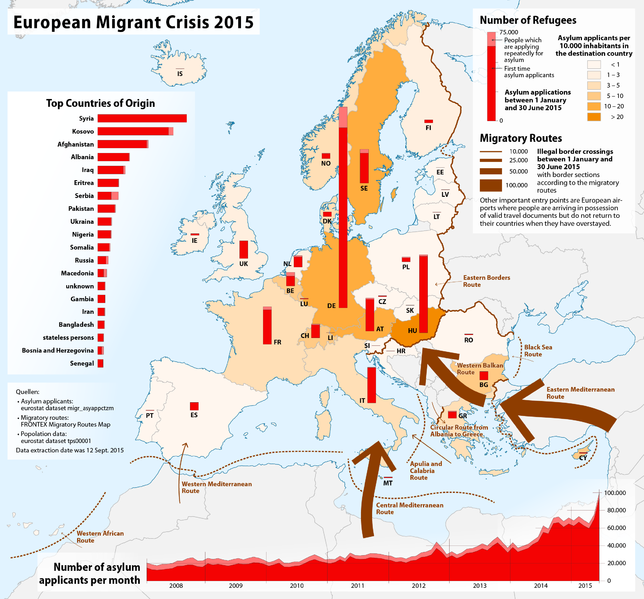

It describes what has happened recently when Syrian, Afghan, and other refugees attempted the difficult journey to member states of the European Union in their ongoing search for safety. By extension, it describes the response of governments and the media to the refugees on Europe’s doorstep, a response many call inadequate.

A Syrian boy waiting for assistance in 2014.

The desperation of these refugees and asylum seekers and the challenges they face should not be minimized. But the shorthand of “refugee crisis” (meaning, in effect, “a crisis for European states,” rather than a crisis for refugees) neglects two fundamental issues.

One consideration is that, since 2011, most Syrian refugees either remain in Syria as internally displaced persons outside the scope of international legal conventions, or have found shelter in adjacent states such as Turkey and Lebanon.

Likewise, Afghan refugees are mainly sheltering in Pakistan: only a minority attempt the hazardous journey to Europe.

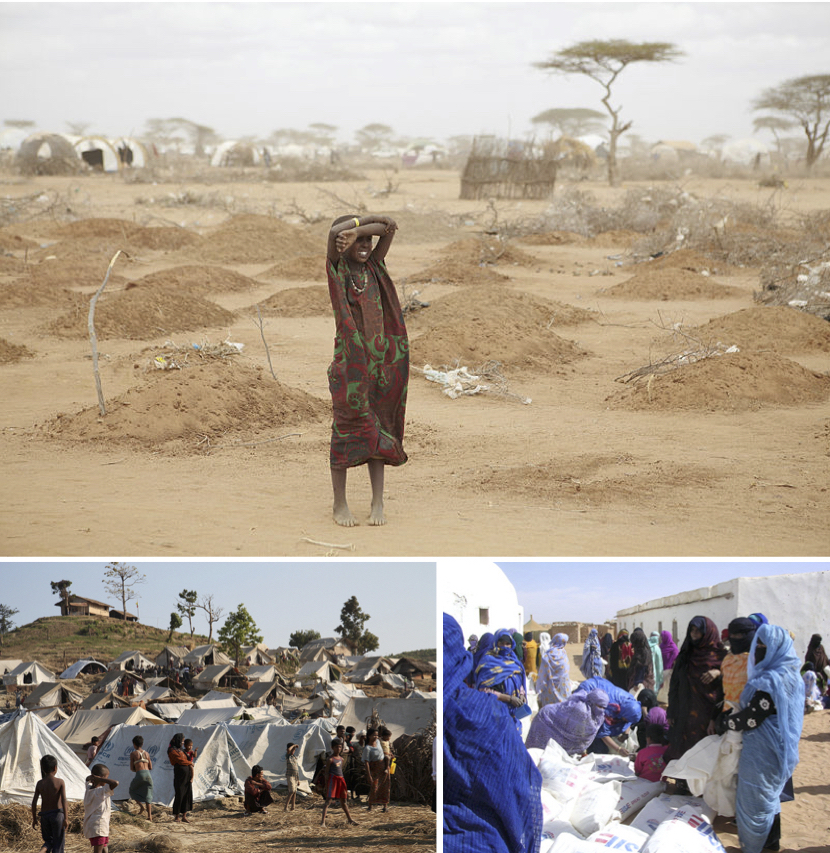

The second problem with current characterizations of the “refugee crisis” is that there are many other refugees whose circumstances rarely make headlines.

Refugees in the Western Sahara, Rohingya in Bangladesh, and Somali refugees who at the time of writing face an uncertain future in the sprawling Dadaab camp complex in Kenya barely register on the radar of the global North.

In short, the spotlight of public attention only illuminates a small part of the stage, leaving other parts of the world lost in the shadows.

To get to the Dadaab Camp in Kenya, refugees from Somalia must first walk for weeks across a desert and many die along the way or soon after arrival. This mass gravesite for 70 children lies just outside the camp (top). The Taung Paw Camp in Rahkhine State, Myanmar (Burma) housing Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh in 2012. Some have been there since the 1990s (left). Saharawi refugee women from the Western Sahara in 2004 gathering to collect flour in the Dakhla refugee camp in Algeria (right).

One of today’s biggest political and ethical questions concerns the marginalization of millions of refugees who face danger and humiliation daily. To the obvious threat of direct exposure to warfare we should add the risk of being denied sanctuary and continuing uncertainty. Their predicament reflects the fact that in a world of nation states, everyone is supposed to have a state of their own.

But refugees who flee or who are forced from their homes face a long and difficult struggle to demonstrate they should even be recognized as refugees under international law and protected accordingly. To be sure, many people, particularly in the global South, who are not refugees suffer from poverty, malnourishment, and ill health—so-called “structural violence”—but refugees confront a loss of citizenship as well.

It is all too easy to conceive of present-day asylum seekers as figures who form part of a nameless and helpless mass, waiting to be “rescued” from the clutches of people smugglers before being “managed”: in other words, being considered for admission as recognized refugees or returned either to their country of origin or to another country deemed “safe.”

There is, of course, an element of truth in this characterization: asylum seekers are at the mercy of governments that decide who to admit. But this is by no means the whole story.

Refugees are active subjects and not mere flotsam and jetsam on the tide of history. They have usually made a conscious decision to seek a place of relative safety from persecution. They are men and women with aspirations and capabilities, as well as a strong sense of their own history.

Unfortunately, much of the mass media in the global North portrays refugees as people who have lost everything, including the capacity to speak or to contribute productively to the host country.

Both issues—the problems faced by refugees and the problem of our attitudes toward refugees—are not exclusively features of the current “refugee crisis.” Rather, they manifested at other times and in other places.

A Century of Forced Migrants, Refugees, and Displaced People

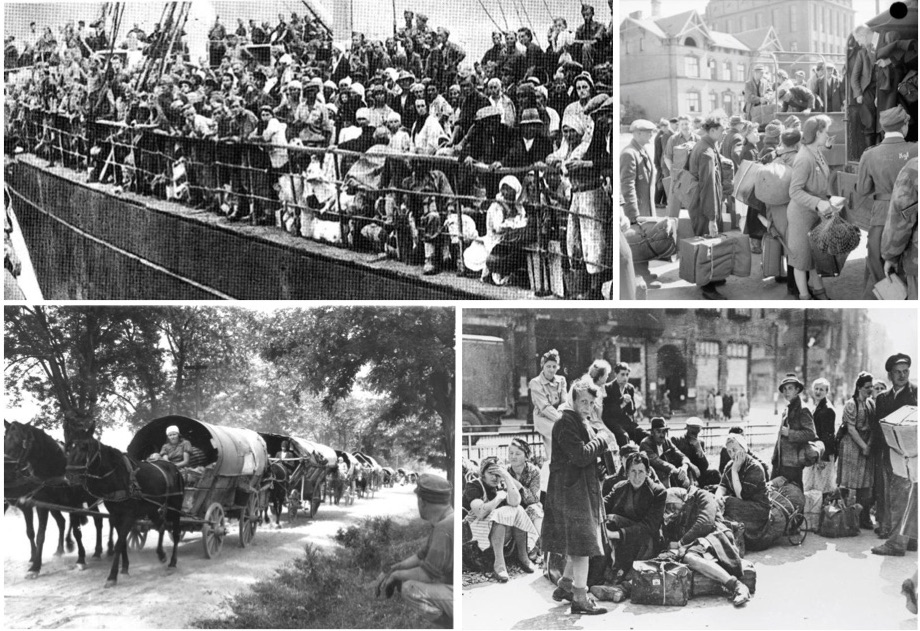

The current refugee crisis is often described as unprecedented. While it is different in many ways, it certainly is not the first time large numbers of people have been forced to leave their homes for any number of reasons. In addition to the two world wars, revolutionary upheavals, decolonization, and civil wars all had the effect of dislocating local populations.

Given the attention the current refugee crisis has received, it is worth reflecting on the fact that the scale of global population displacement after World War II eclipsed by orders of magnitude the numbers we read about today.

Polish refugees sailing to Iran in 1942 (top left). An estimated 120,000 displaced persons were housed on the grounds of the Hamburg Zoo after the British took over the German city in 1945 (top right). Black Sea German refugees fleeing Hungary in 1944 (bottom left). Refugees in 1945 Berlin awaiting transportation (bottom right).

In Europe, some 60 million people were displaced by World War II and its aftermath, including several million ethnic Germans who were unceremoniously evicted from their homes in Poland and Czechoslovakia after the war’s end. But this was only part of the global “refugee problem.”

To this European total we should add at least 15 million in South Asia. One million Palestinians became refugees in 1948 following the creation of the state of Israel. In the Far East as many as 90 million were displaced, partly by the revolution of 1949 that led to the creation of the People’s Republic of China (and the flight of refugees to Hong Kong and Taiwan) but largely as a consequence of the Japanese invasion of China and the prolonged war of occupation between 1938 and 1945.

Chinese refugees returning home in 1944 only to find their homes destroyed (top left). Koreans fleeing south ahead of the advancing Chinese army in 1951 (top right). Palestinian refugees forced to flee after the creation of Israel in 1948 and the ensuing war (bottom).

We will never have an exact count, but World War II and its aftermath may have left 165 million homeless.

This, of course, was the second time that global war led to a refugee crisis. Millions of civilians also became refugees before, during, and after World War I.

Roughly 8 million subjects of the Russian Tsar were forced from their homes during World War I, when the western borderlands of the Russian Empire fell into German and Austrian hands. Some fled for fear of occupation, but Germans, Jews, Poles, Latvians and others were deliberately targeted by the tsarist state as “enemies within.”

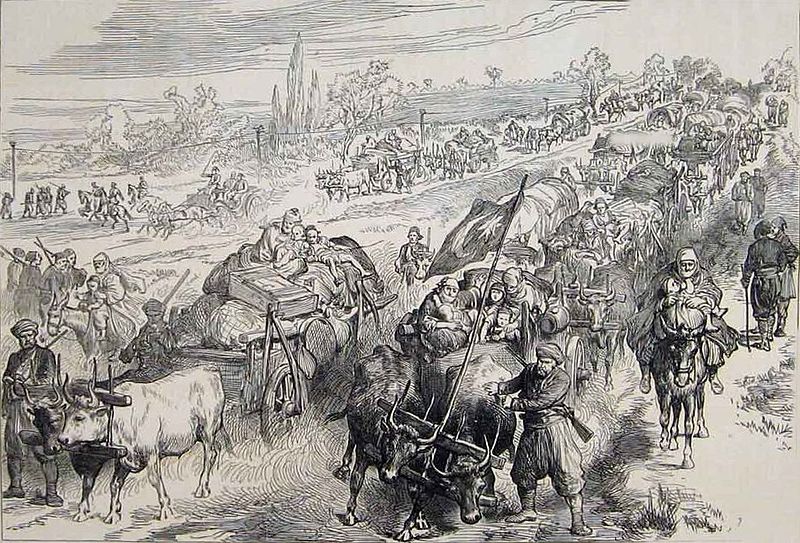

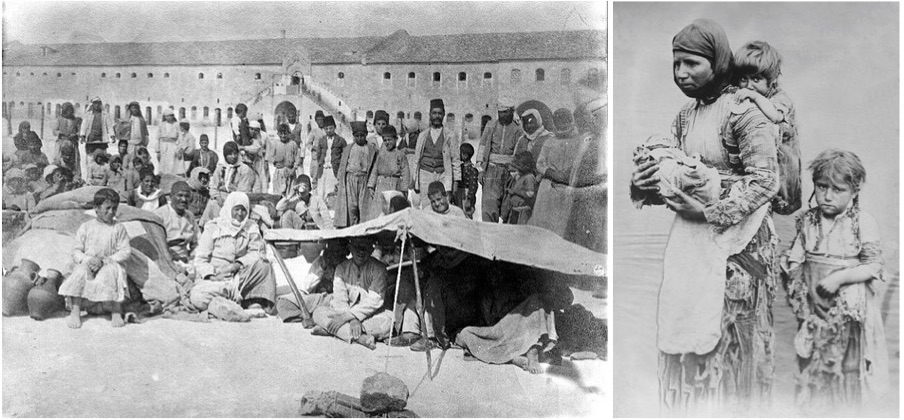

Turkish refugees fleeing in 1877 after Russia seized the Kars region from the Ottoman Empire.

Likewise, conflict in the Balkans led to a refugee crisis as Muslims sought sanctuary in the Ottoman Empire, where their encounter with the local Armenian population was to have tragic consequences in 1915 when the Young Turks enlisted them in deporting Armenians en masse, murdering many civilians and condemning the remainder to death or penury in remote parts of Anatolia. This was but one of numerous instances of forced migration.

Some episodes, such as the mass exodus of Serbians in 1915 following the Austrian invasion, were well known to the survivors and their descendants, but not beyond these confines. Other moments faded from historical consciousness once the immediate crisis had passed.

There were two important exceptions.

A refugee camp for Armenians in Aleppo, Syria in 1918 (left). An image widely used to raise funds for the Armenian Relief Committee. The widowed Amenian woman and her children walked across Turkey seeking help from missionaries after the Armenian Massacres of 1894-1896 (right).

The survival of Armenian refugees, many of whom sought refuge in the French mandate territory of Syria and in France itself, became a matter of international concern, partly because of the numbers involved but also because they symbolized a humanitarian preoccupation with the Christian “victims” of Turkish “barbarism.”

A second focus of international humanitarianism concerned those who fled Russia in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution and ensuing civil war. Both groups attracted the attention of the new League of Nations, whose member states included countries where many refugees arrived in dire straits.

Mass population displacement can also be laid at the door of politicians who sought to redraw the borders of states and redistribute population in order to achieve what they regarded as a desirable and peaceful remedy to existing political and social tension.

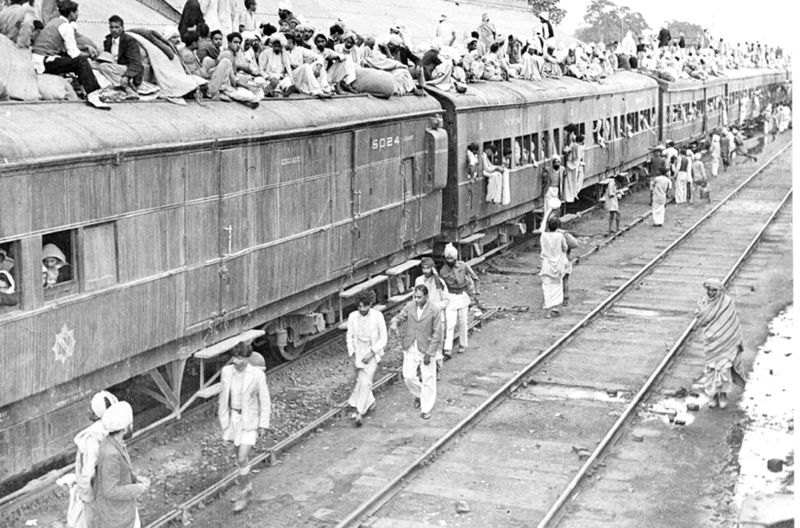

For example, the Partition of India in 1947 following the abrupt end of British rule convinced indigenous political leaders of the need to create two new states, India and Pakistan. Although they never envisaged a mass transfer of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims across the newly drawn frontiers, the consequence was that millions of people moved between the two countries in order to join “their” state and/or to avoid being targeted by those who felt they did not belong. Their future became bound up with the course steered by the new states.

A quarter of a century earlier, European diplomats who gathered at Lausanne, Switzerland, devised a population exchange between Greece and Turkey in order to remove Orthodox Greek Christians from Anatolia and Muslims from Greece. This compulsory exchange of people in the pursuit of ethnic and religious homogeneity was believed to be a price worth paying for future peace. But the net effect was to create a large refugee population in both states.

The International Response to Refugees

The refugee crises around the world in the first half of the 20th century generated an international response.

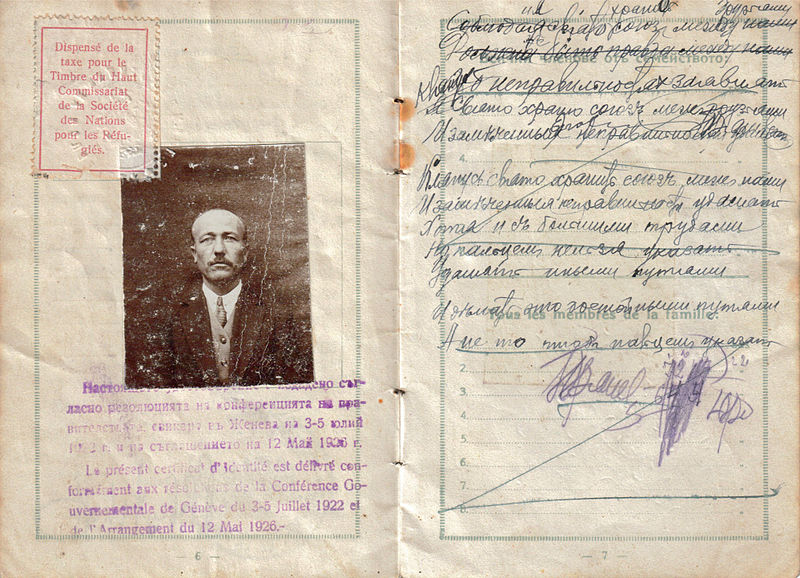

The outcome of the displacements caused by the World War I was that the League of Nations agreed to establish a small office to provide basic assistance to Russian and Armenian refugees who had (as the legal formulation put it) “lost the protection” of their state.

Famously, the new high commissioner for refugees, the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, obtained the agreement of several states to issue an identity document (the “Nansen passport”) that gave refugees a degree of legal recognition and the opportunity to travel between participating countries without hindrance. These refugees were assisted on a day-to-day basis by a growing number of non-governmental organizations.

Other refugees, however, were left high and dry, for example in parts of the world where colonial and imperial powers forced indigenous farmers from their homes. Italian policy in occupied Abyssinia is a case in point.

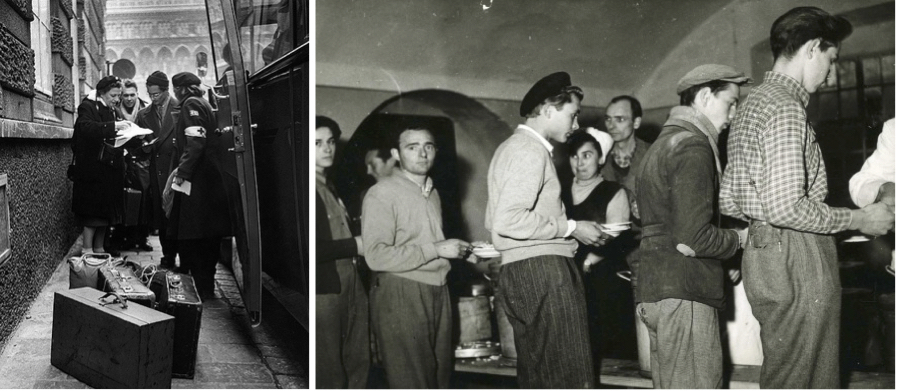

As is well known, this international refugee regime proved of limited use to German and Austrian Jews who sought to escape the Nazi terror during the 1930s, nor did it alleviate the plight of refugees from Mussolini’s Italy and Franco’s Spain.

Children evacuated during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) giving the Republican salute.

It was partly in response to the catastrophe of the Holocaust that postwar governments deliberated over a new framework of legal protection. I say partly, because the growing emphasis upon the need to protect refugees who had suffered persecution took account not only of Nazi policy but also of Soviet totalitarianism.

This is a long and convoluted story, because in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the Allies, Western and Soviet, cooperated in the organized repatriation of several million forced laborers from Germany to their original homes in Eastern Europe. But as evidence mounted that considerable numbers refused the offer of repatriation, the Western Allies came around to the view that these “displaced persons” deserved to be recognized as people who feared fresh persecution.

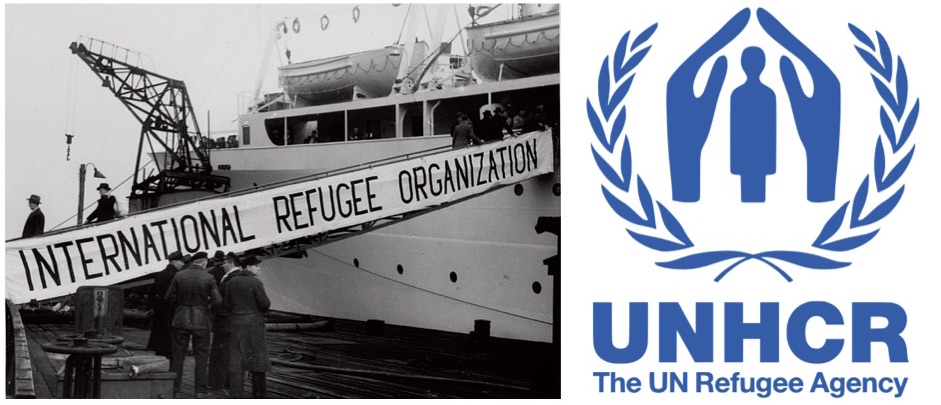

One outcome of World War II was the creation of a key institution, the International Refugee Organization, which was succeeded in 1951 by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) alongside the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

A passenger ship for migrants associated with the United Nations' International Refugee Organization (left). The logo for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which succeeded the International Refugee Organization in 1951 (right).

The Refugee Convention and UNHCR have since been the cornerstone of the international response to refugees.

Crucially, the convention defined a refugee as an individual who has a well-founded fear of persecution on political, social, religious, and ethnic grounds. This replaced the League of Nations’ definition. It also confirmed a prewar principle that refugees who fell within the high commissioner’s mandate could not be returned to their country of origin against their will.

UNHCR started life as a small and temporary organization, and only gradually developed into the lead inter-governmental agency working on behalf of refugees.

One fundamental point needs to be highlighted. State signatories to the convention insisted that its provisions applied to refugees in Europe whose persecution could be attributed to events taking place in Europe prior to 1951. The aim, in other words, was not to write a “blank check” such that governments would be obliged to entertain claims from future refugees.

UNHCR continued to be backed during the Cold War by states that found it politically useful to support victims of communist persecution, including Hungarian refugees in 1956.

The Austrian Red Cross assisting some of the quarter of a million Hungarians who fled in 1956 (left). The British Red Cross fed and housed 7,500 Hungarian refugees in food kitchens like this one in Austria (right).

At the same time, not everyone who fled communism found it possible to claim refugee status—many Yugoslav asylum seekers were refused recognition on the grounds that they were “economic migrants” rather than “genuine” refugees.

As this suggests, these institutional innovations to assist refugees were selective and partial, not universal and comprehensive. This becomes even clearer when we consider events in other parts of the world.

The UN devised separate arrangements for Palestinian refugees, in the shape of the United Nations Works and Relief Agency, whose purpose was primarily to assist refugees who arrived in Gaza, the West Bank, and states such as Jordan and Lebanon that bordered the new state of Israel.

Other refugees—the numerous refugees in Pakistan and India, Chinese refugees in Hong Kong—did not come under the Refugee Convention and were not assisted by the UNHCR’s office. Instead, separate and local arrangements were devised.

Over time, the scope of the 1951 Convention has been enlarged to cover other refugee crises, but many states (including India and Pakistan, and most countries in the Middle East) have never signed it. This has left a great deal of room for individual states, as well as humanitarian organizations and philanthropists, to plug the gap, without being held to very much account.

It is sometimes forgotten that the institutional innovations in post-1945 Europe coincided with ambitious plans for the reconstruction of Europe itself, initially through the European coal and steel community, the forerunner of the European Union.

Post-1945 institutions are now being called into question, with asylum as one of the pressure points, against the backdrop of the other crisis—that of economic austerity. In the EU, the current debacle points to a failure of cooperation and coordination that became evident in the majority rather than unanimous decision to agree to a quota for limited numbers of Syrian refugees to be admitted to member states.

Events in 2016-17 suggest that EU coordination is working to harden borders and to return asylum seekers to “safe” places such as Turkey. The increase in the number of refugees and asylum seekers from the global South prompted suggestions that the Refugee Convention is no longer relevant to the new millennium. Critical voices range from former British Prime Minister Tony Blair to Scott Morrison, the erstwhile Australian Minister for Immigration and Border Protection.

A British member of the European Parliament called for the convention to be interpreted much more stringently to prevent asylum seekers from remaining in the UK while their cases are heard. Meanwhile, UNHCR seems powerless to influence individual governments’ policies.

Of course, the EU has been a dynamic institution, absorbing new members, each with different levels of economic development but also with their own imagined history, which helps to fuel policy disagreements.

The intransigent stance adopted by the current government in Budapest towards refugees is a case in point, replete with references to Hungary’s historic “defense” of Christendom. Such rhetoric makes it unlikely that member states will find common ground for protecting refugees, and harder still for refugees when public opinion is being manipulated in this way.

In October 2016, the BBC World Service hosted a debate in Budapest over Hungary's referendum earlier that month on instituting refugee quotas (left). In response to Hungary closing its borders with Serbia to migrants, Syrian refugees began sneaking across the borders in 2015 (right).

Often overlooked, however, is the progressive stance adopted by non-governmental organizations and religious groups such as the Quakers, beginning in the midst of World War I, who emphasized refugees’ right to be granted asylum—not just the right to claim asylum—and entitlement to the same rights afforded ordinary citizens.

International lawyers who had firsthand experience of persecution and displacement were also sympathetic. Hersch Lauterpacht, for example, objected to the powers reserved to the sovereign state over matters of asylum and advocated a more liberal approach.

Unsurprisingly, governments insisted on their right to determine which refugees had made a valid case for recognition. Nevertheless, it’s worth recalling this utopian moment.

Refugees and the Importance of History and Memory

However international organizations and national governments may interpret the meaning of agreements, history matters profoundly to refugees themselves.

It influences the routes they take at times of crisis. Refugees from the Spanish Civil War, for example, followed the tracks made by earlier generations of labor migrants who moved to France to pick grapes and harvest sugar beet or who had migrated to Argentina.

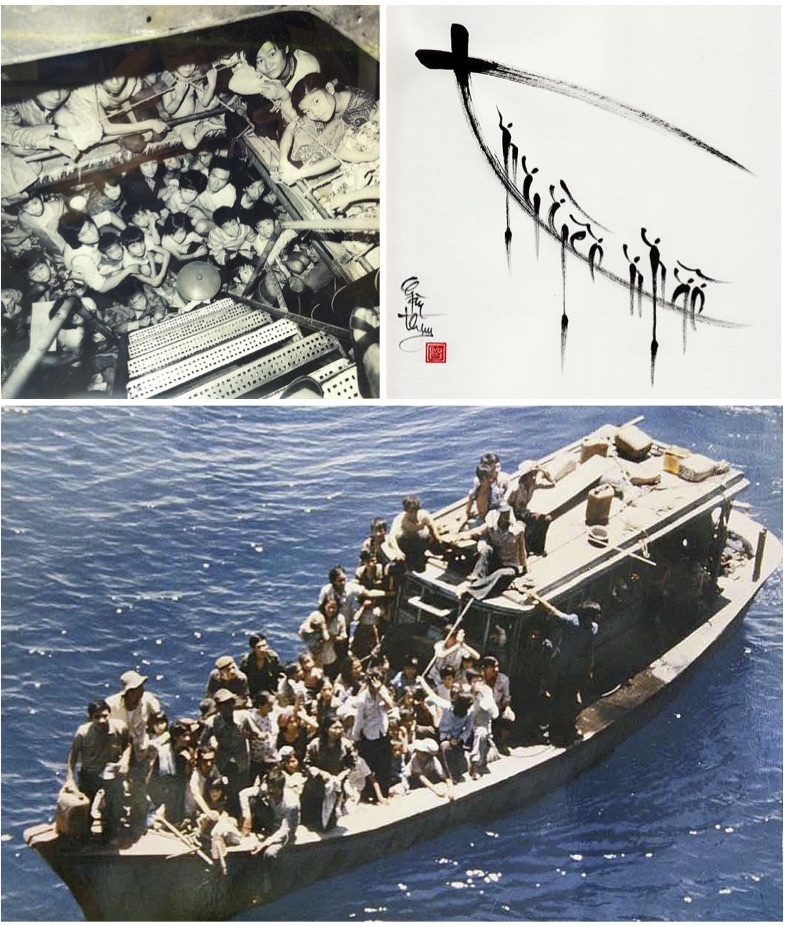

Refugees who fled from North to South Vietnam in the mid-1950s repeated journeys made by family members in the past. Refugees from the bitter civil war in Mozambique sought sanctuary in Malawi to which they were affiliated by virtue of peacetime migration during the 1950s.

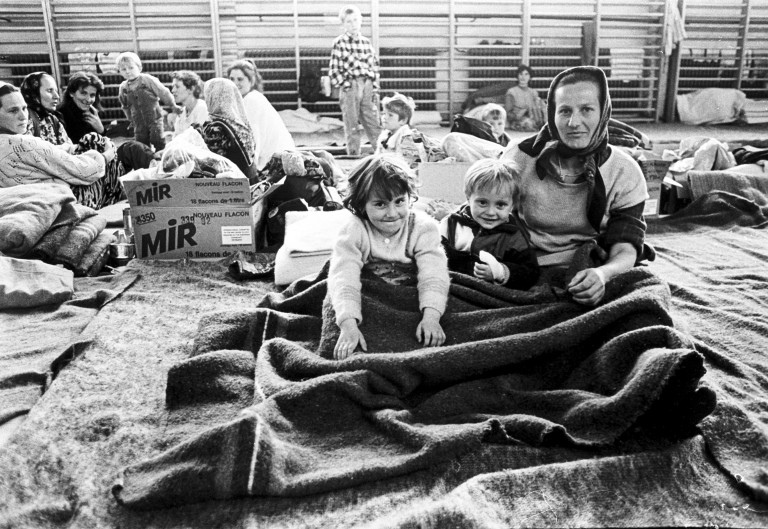

A family in the Tuzla Refugee Camp in former Yugoslavia (c1995).

Bosnian Muslim women who were attacked by Serb militias during the war over the disintegration of Yugoslavia (PDF File) found refuge in Slovenia, because their menfolk traditionally looked for temporary work in Ljubljana and other Slovenian towns and cities. The trajectories of displaced people rarely had a random character but were instead associated with historic ties and networks.

Another way of thinking about the relationship between present and the past is to ask how refugees themselves make connections between one “crisis” and another—in other words how they “joined the dots” in order to help make sense of their predicament. There are impressive instances in which refugees draw upon the history of others’ displacement to make the case for recognition.

For example, contemporary Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers asked for a sympathetic hearing from Israeli government officials, on the grounds that “not so long ago [you] were refugees as well.”

Eritrean asylum seekers in a Tel Aviv, Israel park in 2014 (left). Refugees from Sudan’s Darfur region in a Jerusalem park in 2007 (right).

Further back in time, in the wake of Partition and against the backdrop of external indifference to what was happening on the ground, an Indian government official invited a European audience to “imagine what would have happened if instead of a few hundred thousand people who fled from Europe to Britain during the dark days between 1934 and 1939, the number of refugees had included the whole population of Norway or Denmark.”

Another element in this refugee-centered history is about memory and forgetting.

Refugees have frequently invested in commemorative work, not least by emphasizing the importance of the sudden rupture associated with displacement. One thinks of the boat installations that second-generation Vietnamese refugees have created in countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia to mark their arrival and deliverance – and by extension, to commemorate those who did not survive the journey.

Vietnamese refugees who fled to Hong Kong were detained in small, cramped camps (left). An artist’s depiction of the Vietnamese refugees escaping by boat done in impressionistic calligraphy (right). A photograph displayed at the Vietnamese Boat People Monument in Westminister, California (bottom).

But it is also important not to overlook what is excised from historical accounts.

Refugees have been known to airbrush from history their former neighbors who turned upon them at the moment of displacement. Past social ties are replaced with ideas of ancient enmity. These invented histories can stoke conflict.

Following the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, the Armenian genocide, and the Greek-Turkish population exchange in 1923, the past neighborliness of Christian and Muslim villagers in the Balkans and Anatolia was rewritten as a history of mutual disdain.

To take another example, Hindu refugees who arrived from Pakistan in Delhi in September 1947 and who moved into Muslim houses in the city refused to acknowledge its Muslim past; the same is true of Muslims who wrote the multicultural elements of Lahore out of history. They thereby constructed a historical account in which ethnic and religious violence became “predictable.”

The displaced might think of themselves as a spectral “presence” (as in the memorial books of Armenians, Jews and Palestinians), but they have turned former neighbors into ghosts as well. This is about rewriting the past for present purposes, a politics of negation and oblivion.

The Refugee Crisis: Today and Tomorrow

It is often said that the past weighs heavily on the present, but in the case of refugees this is only partially true. The historical record suggests that the world’s attention is rarely focused on more than a fraction of displacement at any given moment.

What will be remembered of today’s “refugee crisis” once it has passed? Will future historians pay it any attention, and if so, how will they write about it? Or is this a question not for scholars but for refugees themselves?

Previous episodes suggest that it will take time and effort—and a political purpose, such as is characteristic of Palestinian refugees—to mark displacement as a significant moment.

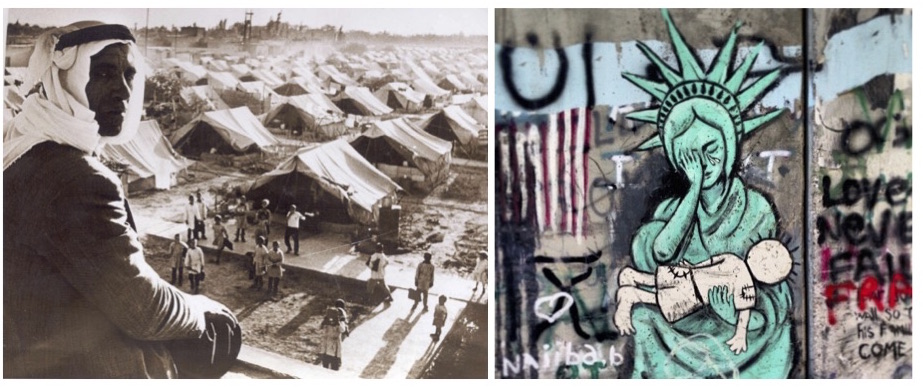

A school at the Jaramana Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria for Palestinian refugees in 1948. The camp still houses Palestinian refugees today (left). An artist’s response to Israel's “security” wall in the West Bank in which Lady Liberty weeps over the Handala, the symbol for the forgotten Palestinian refugees and an iconic symbol of Palestinian defiance (right).

Finally, what is to be done about, and on behalf of, refugees now?

Living in circumstances of great uncertainty, the predicament of refugees in the 20th century called for bold and creative thinking of a kind that is sorely lacking today.

An historical perspective can help us to understand how crises erupted in the past, how they were portrayed, which refugees were protected and how, and in what ways refugees themselves reacted to their predicament. Policy-makers and members of the public might thereby be made aware of the shortcomings of past policy and the consequences of blinkered, harsh, or unresponsive attitudes. We might also recognize what was achieved when imaginative policies were contemplated and adopted.

|

This is not to look at the past through rose-tinted spectacles. It is, however, to acknowledge the achievements as well as the limitations of postwar institutions. They took years to build, and were the product of hard bargaining. Both the UN Refugee Convention and UNHCR adapted to changing circumstances. Like the EU, they are far from perfect.

Yet the utopian strand in postwar thinking—connected to visionary ideas of post-war reconstruction and planning in the case of the European Union, and to an insistence by critical legal scholars that refugees deserved both protection and a meaningful and secure life—badly needs to be resurrected.

And on the subject of leadership and creative thinking, why not ensure that refugees—who have minds of their own—are given ample opportunity to be consulted?

After all, it is their lives and their security that are most directly at stake.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on migration around the world: The Migration Crisis in Europe; Global Migration and the Americas; U.S. Immigration Policy; Operation Wetback; Ellis Island Nation; and the Piraeus Refugee Camp

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Road to Europe: The 2015 Migration Crisis and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, Germany) (English version available) https://www.bamf.de/EN/Startseite/startseite_node.html.

Cohen, G. Daniel (2012), In War’s Wake: Europe’s Displaced Persons in the Post-War Order, New York: Oxford University Press.

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena, Gil Loescher, Katy Long and Nando Sigona, eds (2014), The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gatrell, Peter (2013), The Making of the Modern Refugee, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: the Making of India and Pakistan, London: Yale University Press.

Kushner, Tony (2006), Remembering Refugees: Then and Now, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Loescher, Gil (2001), The UNHCR and World Politics: a Perilous Path, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Loizos, Peter (2002), 'Misconceiving refugees?', in Renos Papadopoulos, ed., Therapeutic Care for Refugees: No Place Like Home, London: Karnac Books, 41-56.

Madokoro, Laura (2016), Elusive Refuge: Chinese Migrants in the Cold War, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Malkki, Liisa H. (1996), ‘Speechless emissaries: refugees, humanitarianism, and dehistoricization’, Cultural Anthropology, 11, no. 3, 377-404.

Marrus, Michael R. (1985), The Unwanted: European Refugees in the Twentieth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/.

UNHCR http://www.unhcr.org/.

Said, Edward, with Jean Mohr (1986), After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives, London: Faber.

Skran, Claudena M. (1995), Refugees in Inter-War Europe: the Emergence of a Regime, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Zolberg, Aristide R., Astri Suhrke and Sergio Aguayo (1989), Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, New York: Oxford University Press.