Boom and bust. That economic cycle has happened repeatedly in places dependent on one natural resource, like Venezuela and petroleum. The history behind the most dramatic economic and human rights crisis in the Americas.

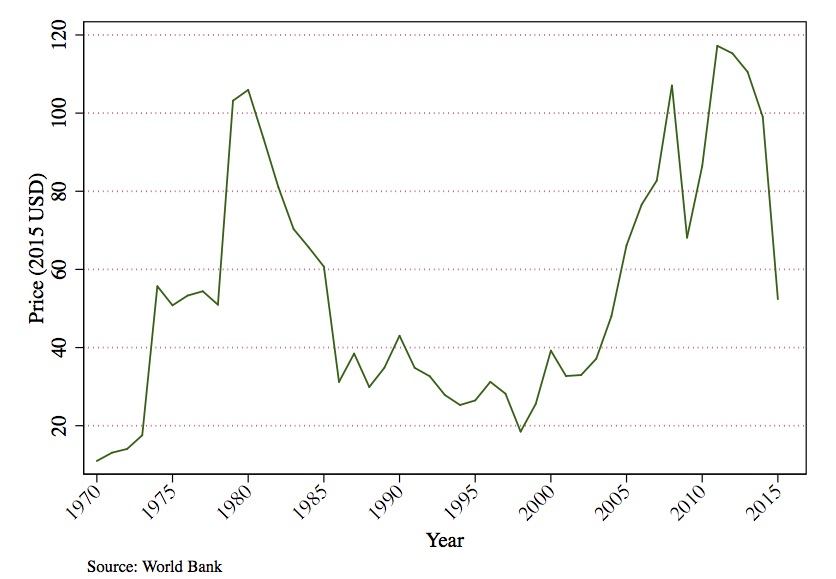

In the 1970s, Venezuela had the highest growth rate and lowest inequality in Latin America. Thanks to an oil bonanza, the government was able to spend more money (in absolute terms) from 1974 to 1979 than in its entire independent history. Indeed, during this time, this Gran Venezuela had the highest per capita GDP in region.

Scotch whiskey consumption was the highest in the world, the middle class drove Cadillacs and Buicks, and the free-spending upper class jetted off on shopping sprees to Miami, where they were known as “dame dos” (“give me two”). Politically, the country was one of only three democracies in Latin America in 1977, along with Costa Rica and Colombia.

Aerial view of Plaza Venezuela in Caracas, Venezuela in 2010.

But Venezuela is now deeply mired in political, economic, and humanitarian crises.

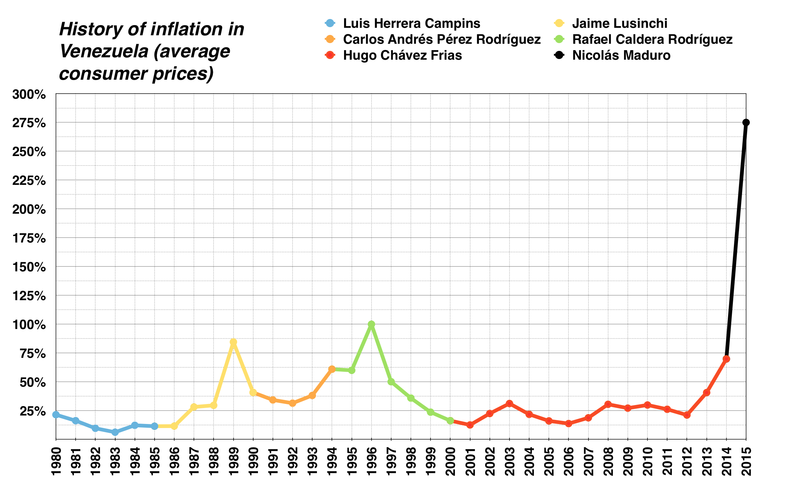

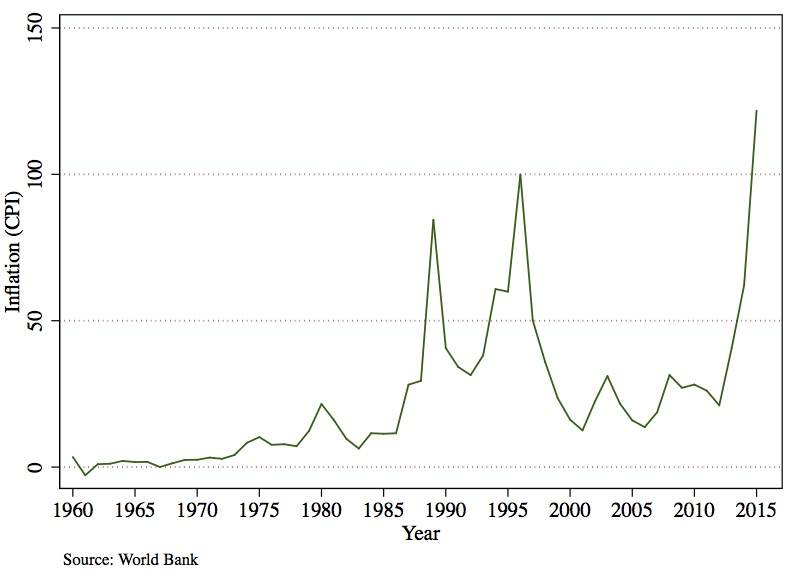

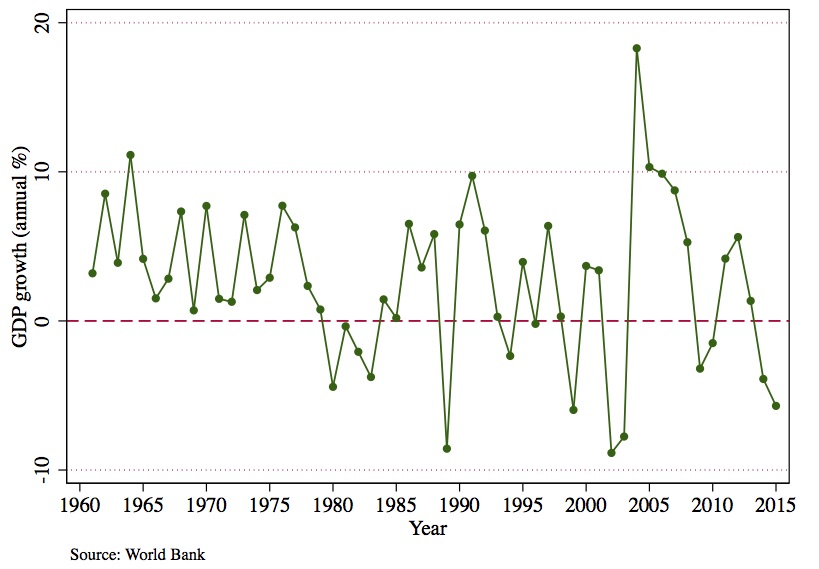

The nation’s economy contracted an estimated 18.6 percent in 2016, and is expected to shrink between 4.3 and 6 percent further in 2017. The 2016 inflation rate was estimated at 290 to 800 percent, and in December 2016 the country became the seventh in Latin American history to experience hyperinflation. Despite the government’s best efforts to continue payments, a crippling debt default also appears likely in 2017.

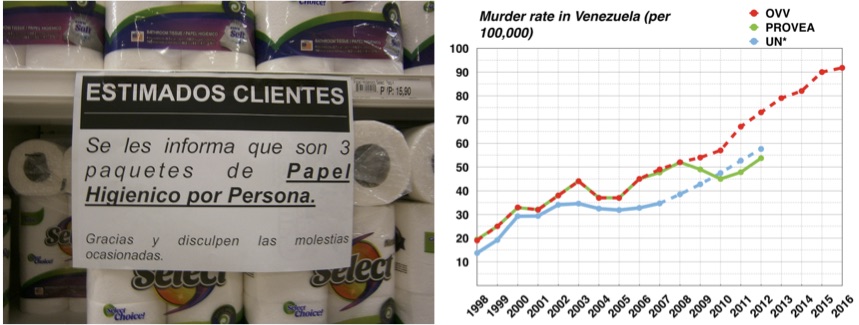

The human costs of the crisis have been dire, with food and medicine shortages, soaring infant mortality, and one of the world’s highest violent crime rates.

Venezuelan inflation rates from 1980 to 2015.

Massive queues for scarce goods like toilet paper, milk, cooking oil, butter, and corn flour (for the country’s ubiquitous arepas) have given rise to professional line standers who are paid to wait on behalf of others, digital apps to help citizens find scarce items, and stories like women giving birth in line or placid observers holding their places while witnessing a murder.

Three-quarters of Venezuelans have lost about 19 pounds of body weight in the last year on what people are calling “the Maduro Diet,” a scathing reference to current president Nicolás Maduro.

Public health is just as bad. As hospitals have run out of imported antibiotics, surgical supplies and spare parts for medical equipment, infant mortality rose 30 percent, maternal mortality 65 percent, and malaria 76 percent in 2016. Diphtheria, once thought eradicated, has made a comeback.

By some estimates, 2.5 million people have left the country since 1999 and Venezuela now leads U.S. asylum requests. On par with these devastating developments, the country has slipped from a hybrid regime—a type of political system that combines democratic traits with autocratic ones—into pure authoritarianism. The government postponed regional elections and suspended an opposition-driven presidential recall referendum against Maduro in October 2016.

Maduro has since tried attempted to dissolve the National Assembly, provoking international opprobrium, massive demonstrations, and condemnation from members of his own party. Some analysts fear the country may be on the brink of civil war.

Toilet paper is one of the basic necessities Venezuela has had a shortage of in recent years. This sign from 2014 limits customers to only three packages of toilet paper per person (left). The murder rate in Venezuela from 1998 to 2016 according to three different agencies (right).

What are the roots of this extraordinary economic and democratic decay?

To begin, Venezuela suffers from the resource curse, where instead of aiding development, the country’s ample mineral wealth actually undermined constructive economic and social development. And although the democracy of the country’s Fourth Republic (1958-1998) was enduring, its quality was not high: the party system was restrictive and unrepresentative of many sectors of society, and it eventually suffered a crisis of legitimacy.

Dissatisfied with the economic situation and a discredited political establishment, voters opted for the promises of the populist Hugo Chávez in 1998.

Chávez managed to radically change the country’s politics and economics without resolving any of the underlying political or economic problems. Instead, his free spending, ambivalent attitude towards liberal democracy, and astonishing economic mismanagement by both him and the feckless Maduro steered the country into today’s crisis.

President Hugo Chávez greeting supporters ahead of his election as president in 1998 (left). President Nicolás Maduro, Chávez’s handpicked successor, wearing the presidential sash in 2015 (right).

Oil Dependency and the Resource Curse

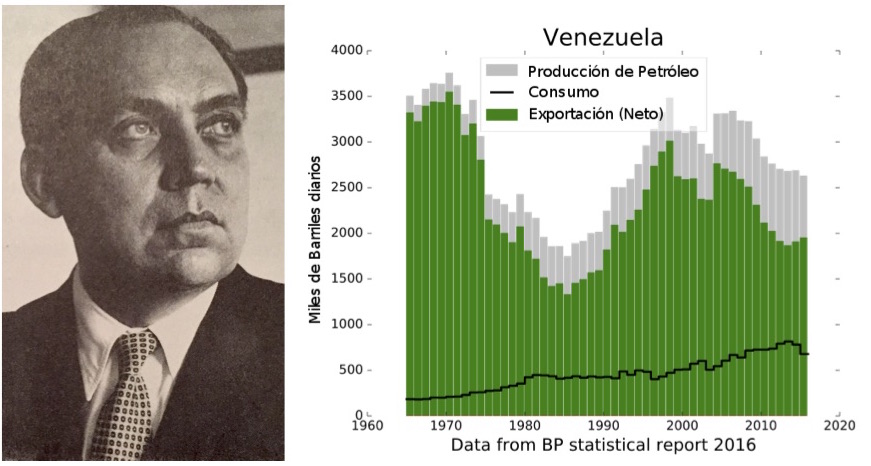

Venezuelan diplomat Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), predicted that Venezuela’s dependence on petroleum would leave it destitute. Amid the oil boom of the 1970s, he prophesied, “Ten years from now, twenty years from now, you will see; oil will bring us ruin ... It is the devil’s excrement.”

The statement proved prescient.

Unlike some of its neighbors, which were long dependent on exporting a single commodity but have since diversified, Venezuela is a rentier state wholly dependent on the extraction and export of petroleum and its derivatives. The oil sector is the country’s largest source of foreign currency, the biggest contributor to the fiscal sector, and the leading economic activity. In 2016, revenue from petroleum exports accounted for more than 50 percent of the country’s GDP and roughly 96 percent of total exports.

A graph showing oil as a percentage of export earnings in Venezuela from 1998 to 2013 (graph created by the author from information from the Venezuelan Central Bank).

This level of dependency causes a “paradox of plenty,” or “resource curse,” in which a country with large natural resource endowments is nonetheless hard pressed to develop. It also leads to corruption, since a limited number of people generate wealth and the government plays a central role in distributing it. In places with weak representative institutions, oil booms—which create the illusion of prosperity and development—may actually destabilize regimes by reinforcing oil-based interests and further weakening state capacity.

All of this has happened in Venezuela, where oil dependency has contributed to at least three recurrent problems. First, it is difficult for dependent states to invest oil rents in developing a strong domestic productive sector.

Abundant revenue from natural resource extraction discourages the long-term investment in infrastructure that would support a more diverse economy. Venezuelan leaders have long recognized this challenge. In a famous 1936 op-ed, writer and intellectual Arturo Uslar Pietri urged his countrymen to “sembrar el petróleo” (plant the oil) by using oil rents to grow the country’s productive capacity, modernize, and educate.

Venezuelan intellectual Arturo Uslar Pietri urged his fellow citizens to use oil profits to develop the country and its people (left). A graph of Venezuela’s production (grey), consumption (black line), and exportation (green) of oil from 1965 to 2015 (right).

Leaders have been unable to heed his advice. Instead, mini-booms in oil prices consistently reverse growth in Venezuela’s non-oil sector, which sees an average 3.3 percent growth in pre-boom years turn into -2.8 percent in post-boom years.

The result is continued dependence on oil revenue at the expense of other industries, and a concentration of risk in a volatile commodity. As the above graph shows, oil dependency has grown since 1998, as the percent of export earning derived from petroleum rose from under 70 percent to more than 95 percent in 2012—and a reported 96 percent in 2016.

Second, in times of bonanza, oil rents may also cause a growing dependence on foreign imports at the expense of domestic industry.

This is due to the fact that new discoveries or rapidly rising prices of oil bring a sharp inflow of foreign currency. An increase in currency reserves leads to appreciation in the value of the currency, which hurts the competitiveness of the other products on the export market and increases dependence on foreign imports, which are cheaper. When oil money is flowing, imports increase.

However, when crude prices drop and petrodollars fall, as they have now, it becomes more difficult for the government to import goods, as demonstrated by scarcity in the 1980s and again since 2012. Compounding things right now, Venezuela’s government has made it a priority to pay its sovereign debt obligations rather than import more goods.

A third consequence of the resource curse is endemic corruption. Countries heavily dependent on external rents, such as natural resource exports, are able to embark on large public expenditure programs without having to develop a fiscal system to tax their populations. As a result, citizens have reduced incentives to hold the government accountable.

Further, whenever public agents have monopoly power and discretion over the distribution of valuable rights, incentives for corruption increase. This has long been the case in Venezuela, which has suffered from public sector corruption dating back at least to democratization in 1958. As oil prices skyrocketed in the late 2000s, horizontal checks on executive power and oversight of the state-run oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, SA (PDVSA) decreased. Today, corruption has reached unprecedented levels.

This is reflected in the evolution of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index in Venezuela. The country consistently ranked in the top 10% of the world’s most corrupt countries beginning with the first survey in 1995. Yet probity has dipped further since the mid-2000s, reflecting decreasing confidence in any measure of government rectitude under both Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro.

The Military, Democratization, and “Partyarchy”

Political factors such as a tradition of military government, late democratization, and weak democratic representation have also greatly contributed to the present crisis.

Simón Bolívar, known at El Libertador, was a military and political figure who played a leading role in bringing independence from Spain to Venezuela, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Panama (left). A 2014 military parade to commemorate President Hugo Chávez’s death in 2013 (right).

Independence hero Simón Bolívar supposedly said that “Ecuador is a convent, Colombia a university, and Venezuela a military barracks.” Indeed, the Venezuelan armed forces have been key actors in Venezuelan politics and state building. Until Julián Castro’s military dictatorship in 1858, all post-independence leaders were ex-military officers who represented the Liberal and Conservative parties.

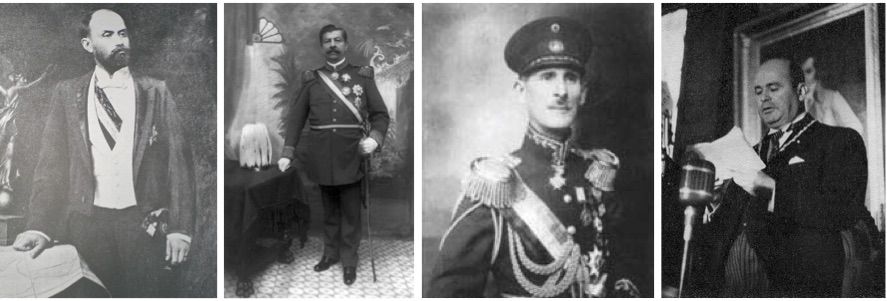

Alternation between active and retired officers holding political power ended definitively with the Liberal Restoration Revolution of 1899. From that time until 1945, a succession of military officers ruled the country under dictatorship: Cipriano Castro (1899-1908); Juan Vicente Gómez (1908-1935); Eleazar López Contreras (1935-1941); and Isaías Medina Angarita (1941-1945).

President Cipriano Castro ruled Venezuela from 1899 to 1908 after seizing power with his personal army (left). President Juan Vicente Gómez seized power from his predecessor and ruled from 1908 until his death in 1935 (second from left). President Eleazar López Contreras served as his predecessor’s War Minister before ruling Venezuela from 1935 to 1941 (third from left). President Isaías Medina Angarita also served as his predecessor’s War Minister and ruled Venezuela from 1941 until 1945 (right).

The country attempted electoral democracy during the trienio adeco (1945-1948), but this was quickly followed by the repressive dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez. In the absence of interstate conflict, the armed forces saw themselves as the key institution fostering internal development and modernization.

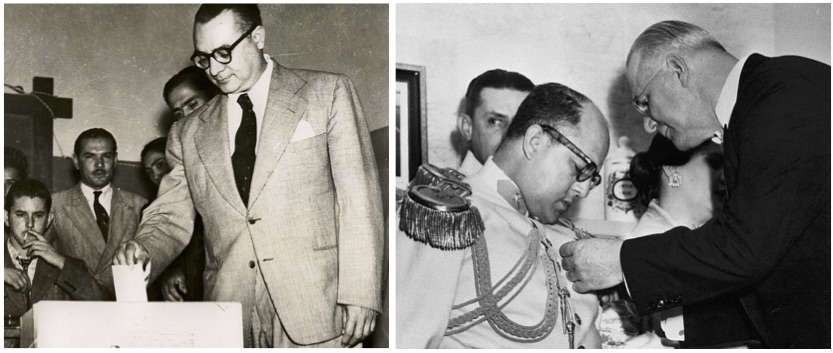

Military involvement in politics meant democracy arrived late. Stable democracy, in fact, did not occur until 1958, when representatives of Venezuela's three main political parties—the Social Democratic Acción Democrática (AD), Social Christian COPEI and Unión Republicana Democrática (URD)—signed a formal agreement known as the Pact of Punto Fijo.

President Rómulo Betancourt, the “Father of Venezuelan Democracy,” voting in 1946 (left). President Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who ruled as a military dictator from 1952 to 1958, receiving a commendation from U.S. Ambassador Fletcher Warren in 1954 (right).

The pact aimed to preserve democracy through elections, cabinet and bureaucratic power sharing, and a basic program of government. Although the accord allowed Venezuelan democracy to survive the tumultuous 1960s and a leftist guerrilla threat, as well as destabilization attempts by the Dominican Republic’s right wing dictator, Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, it also helped bind Venezuela’s political system to exclusive competition between two parties, AD and COPEI, after the URD lost power in the 1960s.

This two-party dominance created what Michael Coppedge termed “partyarchy”: government of the people, by the parties, for the parties. In it, AD and COPEI exercised a “pathological kind of political control” over political, economic, and social life that guaranteed stability at the expense of representation.

The parties relied on a system of concertación, in which they would confer with each other or business and military interests to seek consensus on major policies. They also used patronage to coopt civil society organizations and other means of limiting channels of representation such as interest groups, the media, and the courts.

From left to right, Rafael Caldera, Jóvito Villalba, and Rómulo Betancourt at the signing of the Pact of Punto Fijo in 1958 (left). The logo of the Social Democratic Party, Acción Democrática, (AD) (top). Members of the Social Christian Party, COPEI, marching for a mayoral candidate around 2010 in the party’s trademark green color (bottom).

These limitations hurt the system, and as oil prices fell and resources for patronage dried up in the 1980s, public support for the parties and the Fourth Republic democratic system declined.

Venezuela’s achievements in the 1960s and 1970s, look less impressive through the prisms of oil dependency and democratic rigidity. While GDP per capita, social spending, and quality of life all rose, and while the country avoided the democratic collapses of Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, and others, its gains were ultimately unsustainable.

These fundamental political and economic weaknesses also created conditions for the crises of the 1980s and 1990s and paved the way for the allure of populism and the explicit involvement of the armed forces in politics in the 2000s.

Economic Crisis and the Unraveling of Partyarchy

The economic shoe was the first one to drop, as oil prices collapsed in the early 1980s. High public debt, the drying up of international loans, and an overvalued currency led to massive capital flight in 1982 and early 1983.

On February 18, 1983, or viernes negro as it is known in Venezuela, the government established currency controls—something Chávez would do 20 years later—to stop this flight and halt inflation. Purchasing power declined by almost 75 percent overnight.

Partyarchy also began to crumble.

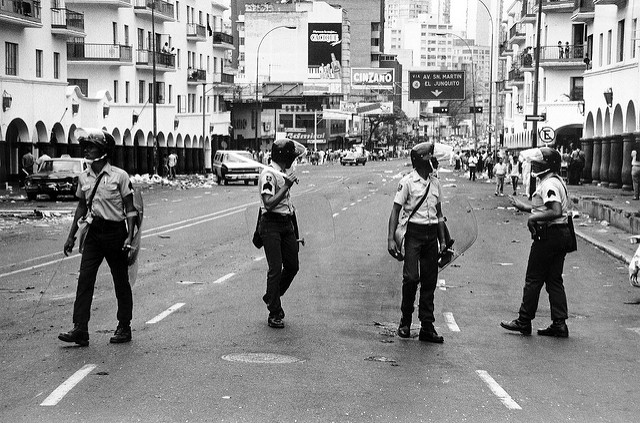

Buffeted by low oil prices and rising interest rates on its international debt, the Venezuelan government struggled to finance itself. President Carlos Andrés Pérez attempted a fix through a packet of neoliberal economic reforms in February 1989, but they only further aggravated the economic situation for the working class, leading to a wave of protests, riots, and looting on February 27 that left hundreds of civilians dead.

Police patrolling after the riots, known as Caracazo, in February and early March of 1989.

In its wake, the Revolutionary Bolivarian 200 Movement (MBR-200), a radical left-wing group led by Army Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez Frías, accelerated its planning for a coup d’état. This February 1992 coup attempt was unsuccessful—as was a second attempt by the Air Force in November of that year—but it marked the beginning of the end of Punto Fijo democracy.

A deep institutional crisis followed during the 1990s with the impeachment of Pérez in 1993 and a major financial and economic crisis during the Rafael Caldera administration (1994-1999) that coincided with the lowest international crude prices in decades.

Chavismo: Erosion of Liberal Democracy and Populist Economics

Conditions were ripe for the emergence of a political outsider. The individual to capitalize on voters’ disaffection with the political and economic status quo was the charismatic and flamboyant Chávez, who had gained a national profile after his failed 1992 coup.

Campaigning on a platform of “Bolivarianism,” a radical reimagining of the state that included economic and political sovereignty, self-sufficiency, democratic socialism, and participatory democracy, Chávez promised a break with Venezuela’s unjust political and economic systems. Among other things, he pledged to establish a constituent assembly to rewrite Venezuela’s constitution and enshrine Bolivarianism as law.

Campaign posters for Hugo Chávez’s reelection in 2012 (left). President Hugo Chávez in his trademark red beret and Venezuelan flag tracksuit in 2013 (right).

As a political outsider, he argued that he would end public sector corruption. Most importantly, he promised to eradicate poverty, expand state services to the poor and working classes, and incorporate these excluded groups into the political process. His electoral gambit worked, as he defeated the conservative Henrique Salas Römer with a resounding 56.2% of the vote, and began the first of four terms in office.

Armed with majority (and at times supermajority) support in the National Assembly, Chávez was a polarizing figure, adopting a majoritarian-style, plebiscitary interpretation of democracy that largely ignored the views and values of his opposition.

In his incendiary speeches he denigrated political opponents as escuálidos (feeble ones), rancid oligarchs, and lackeys of imperialism, among other insults. Members of the non-revolutionary bourgeoisie were “pitiyanquis” (little Yankees) and opposition politician Henrique Capriles a “low life pig.”

The war went beyond words. In 2004, National Assembly member Luis Tascón published a list of the millions of Venezuelans who petitioned in 2003 and 2004 for Chávez’s recall, leading the government to discriminate against signatories.

Politically, the president moved slowly to accumulate power and eliminate checks on his socialist project: he packed the courts, filled the ranks of the military with loyalists and integrated the armed forces into politics, systematically dismantled independent media, and, in the wake of a general strike in 2002-2003 aimed at removing him, replaced opponents within PDVSA. Buoyed by a favorable economic situation, high approval with his base, and a fragmented opposition, the president won reelection in 2000, 2006, and 2012.

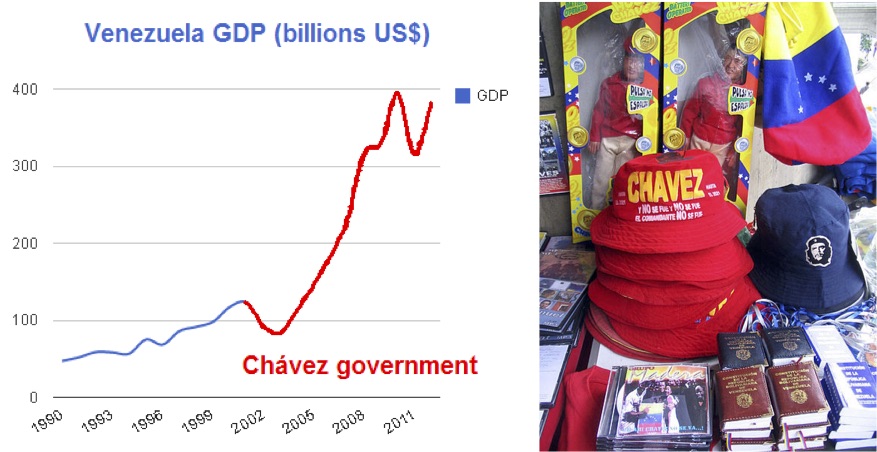

Venezuela’s Gross Domestic Product rose from 1990 to 2011, especially during Hugo Chávez’s presidency (left). Beloved by many, street vendors in Venezuela sold action figures of President Hugo Chávez and hats in the president’s trademark red color in 2006 (right).

But Chávez was not a democrat by conviction so much as by convenience. He turned to elections as a route to power only after his failed 1992 coup, and rarely tolerated the dissenting voices characteristics of democratic pluralism.

By the time of his death in 2013, Venezuela was neither a liberal democracy nor a dictatorship, but a hybrid regime in which the political playing field was decidedly tilted in favor of the governing Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela).

Liberal democracy also suffered due to a blundering and often divided political opposition. Perhaps the most short-sighted and detrimental action was a failed military coup against Chávez in 2002, which provided him an opportunity to question the democratic values of this political coalition, while simultaneously allowing him to restructure the armed forces and remake it into a far more ideological and regime-loyal institution.

The general strike of 2002-2003 against his government likewise provided justification for the removal of some 18,000 PDVSA employees, while subsequent boycotts and demonstrations have frequently served to strengthen the regime and demonstrate its superior force. In 2005 the five major opposition parties withdrew from legislative elections over a dispute about the voting process, providing Chávez the luxury of a parliamentary supermajority and law-making carte blanche for a five-year period.

President Hugo Chávez at a meeting of the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela in 2008 (left). A 2007 rally to celebrate the fifth anniversary of President Hugo Chávez surviving the 2002 coup attempt (right).

Economically, the ruling party was aided by a surge in oil prices, which grew from under $10 a barrel in 1999 to more than $140 in 2008. Flush with cash, Chávez was able to pursue an ambitious domestic and foreign policy agenda. Government social spending targeted the popular classes, especially the misiones sociales (social missions) that brought state services such as health care, education, and subsidized food to the poor.

At the peak of the oil boom from 2006 to 2011, Venezuelans’ quality of life improved at the third-fastest pace worldwide according to the United Nations’ Human Development Index. From 1999 to 2009, poverty decreased, unemployment fell from 14.5 percent to 7.6 percent, GDP per capita grew $4,105 to $10,810, and infant mortality fell from a rate of 20 per 1,000 live births in 1999 to a rate of 13 per 1,000 live births in 2011.

However, these improvements were largely ephemeral. As with the Pérez government in the 1970s, economic improvement under Chávez hid structural debilities and a profound democratic deficit.

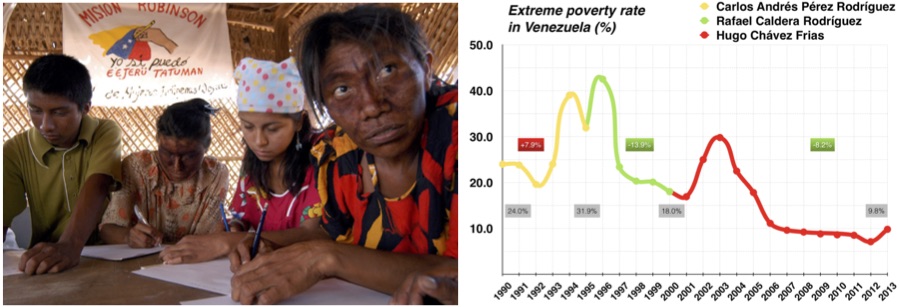

A social mission class in northern Venezuela teaching reading and writing in 2004 (left). The percentage of Venezuelans in extreme poverty has decreased since 2003 (right).

Instead of building up Venuezela’s foreign-exchange reserves or creating a diversified investment portfolio to reduce the economy’s long-run exposure to petroleum, Chávez continued to spend freely at home and even sent oil abroad at preferential rates in an attempt to cultivate regional allies.

He also made three costly policy decisions: expropriating private enterprises, establishing currency exchange controls, and instituting price controls on many basic necessities. As oil prices have fallen since 2011 and the government is able to import fewer goods, the result of these three economic decisions has been devastating.

The first of these was the expropriation or nationalization of numerous private enterprises, including oil, agriculture, finance, heavy industry, steel, telecommunications, power, transportation, and tourism—especially after Chávez was re-elected in 2007. While the government expropriated only 15 private enterprises from 2002-2006, it seized 1,147 between 2007 and 2012.

President Hugo Chávez befriended Fidel Castro in the 1990s and supplied Cuba with oil at a reduced rate (left). The Presidents of Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Venezuela signing an agreement in 2007 to establish the Bank of the South, a monetary fund and lending organization to support left-leaning South American nations with infrastructure and social projects (right).

The effects have been disastrous.

These expropriations not only closed productive sectors and replaced them with inefficient state-owned enterprises, but they also helped drive away investors. State seizures of private businesses have damaged the productive sector, forcing Venezuela to double down on imports.

A second persistently problematic policy is foreign currency controls. In an attempt to force a vote to recall Chávez, the political opposition organized a massive general strike from December 2002 to February 2003, causing an oil stoppage that reduced production to one-third its previous levels.

To deal with loss of revenue, Chávez fixed the exchange rate between the local bolívar and the U.S. dollar and gave the government the authority to approve or reject any purchase or sale of dollars. The measure was a short-term remedy and a ticking time bomb. With a decline in dollars, black market demand for the currency skyrocketed (causing some Venezuelans to engage in the so-called raspao and other forms of arbitrage).

Instead of lifting currency controls and normalizing the exchange rate, the current Maduro government continues to print more money, further raising the de facto inflation. The below graph demonstrates this nicely: while inflation dropped after spiking in 2003, it increased in 2009 and has shot up rapidly since then.

Inflation in Venezuela from 1960 to 2015 (graph created by the author).

Moreover, with currency controls in place, private companies cannot import the raw materials they need. Multinational corporations such as Bridgestone, Clorox, General Mills, and others have pulled out of the country due to the difficulty of importing raw materials.

In early 2016, Coca-Cola briefly halted production at two of its bottling plants due to a sugar shortage. Meanwhile, the country’s largest brewer, Cervecería Polar, was unable to produce beer because it had not received foreign currency to import malted barley.

A third damaging economic policy has been strict governmental restrictions on prices for a range of foods and goods. Price controls on key products have been a constant in Venezuela since World War II to make basic necessities more affordable for the poor, but they were never as deep or widespread as under Chavismo.

The Chávez and Maduro governments have set prices so low that companies and producers cannot make a profit on the goods, resulting in scarcity. As a result, farmers grow less food, manufacturers cut back production, and retailers stock less inventory. The government expropriations deepen the problem, since some of the shortages are in industries, such as dairy, sugar, and coffee, in which the government has seized private companies and is now attempting to run them.

Unable to obtain sufficient stock, many stores like this one in 2013 had empty shelves (left). A line of customers hoping to buy some of the few goods available stretches outside a grocery store in 2014 (right).

In sum, when oil prices were high, Chávez made economic policy decisions that yielded short-term dividends but long-term losses. Since oil prices have dropped, these decisions have turned catastrophic.

Nicolás Maduro: From Bad to Worse

After Chávez’s death in 2013, his chosen successor, Maduro, narrowly defeated Henrique Capriles of the opposition Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) coalition in the April 2013 election. The less charismatic Maduro has confronted falling oil prices and low popularity by doubling down on the late Chávez’s policies, tying his political survival to that of senior military officers and clamping down on dissent, moving Venezuela from a hybrid regime to an outright authoritarian one.

President Nicolás Maduro courted voters in 2013 via the popularity of the late President Hugo Chávez. The sign reads: “Chávez, I swear, my vote is for Maduro” (top). In 2016, on the third anniversary of Chávez’s death, Maduro—wearing Chávez’s iconic tracksuit—attended a commemoration for the late president (bottom).

First, the military has become an increasingly influential actor within the Maduro regime, and is in many ways a “de facto branch of Chavismo.” After his appointment in July 2016 as head of national food distribution and a coordinating chief of staff, Minister of Defense General Vladimir Padrino López has become one of the most influential leaders in the country. Chávez politicized the organization beginning with a series of purges and new patterns of regular reassignment since the failed 2002 coup, and he named close senior military officials to government positions.

Other officers have been accused of complicity in narcotrafficking and corruption. Maduro recognizes the enormous power the armed forces wield, as well as their vested interest in maintaining the status quo, and has named their leaders to cabinet positions, shielded them from foreign indictments, and surrounded himself with officers.

Despite the deleterious effects of price and currency controls, expropriations, and control over food distribution, the government is unwilling to deviate from its course. Instead, Maduro’s response has been more of the same.

The president’s economic advisors have pushed for more state controls on manufacturing and food supply instead of pursuing orthodox macroeconomic strategies such as loosening price controls, disarming the complex currency exchange controls, and reducing the amount of currency in circulation.

Venezuela’s GDP growth as a percentage from 1960 to 2015 (graph created by the author).

Additionally, officials who enjoy preferential access to dollars and thus benefit from the foreign exchange system have little reason to lift price controls, and it would be anathema to Chavismo to consider privatizing previously expropriated and nationalized industries. These signs are troubling for an economy that has contracted in both 2015 and 2016.

The near term is grim.

The oil industry is in bad shape, as heavy Venezuelan crude has been trading at $45-55 per barrel in 2017. Yet production continues to decline as broken equipment sits idle and the existing wells pump at far below capacity. Unless oil prices rebound significantly or the government finds new lines of credit, Venezuela is nearing a default on its $10 billion debt.

Politically, Maduro has tightened his grip on power by engaging in growing repression and blocking or impairing legal avenues for dissent and politicking. He has jailed critics or opponents as political prisoners, purged the state of public servants who favored the 2016 recall referendum, and militarized a large part of its public security apparatus. After Chávez’s death, there were about a dozen political detainees. Today, there are more than 117 in the country.

A protest against the arrest of protestors, particularly Leopoldo Lopez—a popular politician arrested in 2014 (top left). A child protestor asking for freedom for her mother, a political prisoner (top right). A 2014 sign detailing why Venezuelans protest: insecurity, injustice, shortages, censorship, violence, and corruption. The red box at the bottom declares: “Protesting is not a crime. It is a right.” (bottom).

Since the government postponed regional elections and suspended the presidential recall referendum in October 2016, the country can now be classified as authoritarian. Political dialogue has so far failed to produce any meaningful resolution or compromise.

Instead, on March 29, the Venezuelan Supreme Tribunal (TSJ) announced it would assume the National Assembly’s parliamentary functions so long as the popularly elected organ remains in desacato (contempt of court)—essentially dissolving the opposition-led assembly before international pressure and backroom negotiations led to a reversal.

This move appears to be the straw that broke the camel’s back for the opposition. Hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans have taken to the streets daily to protest the government and demand elections. Confrontations with state security forces have resulted in at least 50 deaths.

A protestor attempting to block the police during "the mother of all marches" in April 2017.

Latin American political leaders, major league baseball players, and even the Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel, long silent on political matters, have condemned government repression.

But the government has remained intransigent.

After the “mother of all marches” on April 19, in which tear-gassed protestors were pushed into Caracas’s sewage-infested Rio Guaire, Maduro retweeted a photo referring to them as human excrement. On May 2, he provoked further crisis by calling for a new constitution under a handpicked, non-democratic constituent assembly. As conditions continue to deteriorate, the country could soon reach a breaking point.

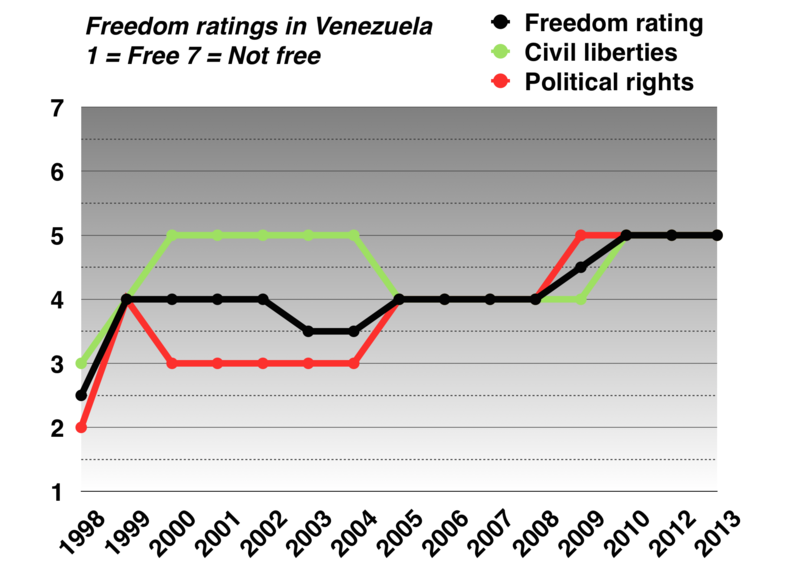

Freedom ratings in Venezuela from 1998 to 2013.

Lessons for the Future

Venezuela’s misfortune offers a number of lessons.

Politically, it suggests that free and fair elections are necessary but not sufficient for democracy, and that democracy requires effective ongoing citizen participation, political representation, and political equality.

Similarly, it also shows how easily states can move among dictatorship, democracy, and hybrid regimes. Countries with shallow democratization or limited representation like Venezuela are at a greater risk of democratic backsliding than places where voters possess high political efficacy and feel represented.

A massive protest against President Hugo Chávez in 2004.

Economically, this experience offers a case study of the dangers of resource dependency—especially in the context of underdeveloped institutions. Oil grew Venezuela’s economy, but generated a reliance that has undermined development.

The country’s wealth, like that of so many commodity-dependent places, was more illusory in the 1970s and the 2000s than many believed. This also suggests that a rise in oil prices right now would be palliative rather than curative, since the same structural problems would continue to plague the economy. Resource-dependent countries need to find a way out of the vicious cycle of the resource curse in order to build their productive economy.

Lastly, Venezuela’s crisis shows the real and immediate effects that dogmatic policymaking has on economies and societies. There are plenty of oil-dependent, weakly democratic states in the world, but none that has experienced the type of implosion that Venezuela has.

Hugo Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, and the PSUV made—and continue to make—reckless political and economic decisions. Just as the current depths of Venezuela’s crisis were avoidable, so too is its occurrence in other places.

The views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of or endorsement by the United States Naval Academy, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the United States government.

Read and Listen to Origins for more on Latin America: Colombia and the FARC; Cuba and the U.S. Reengage; Inflation and Argentina; Rethinking Cuba Libre; Global Migration and the Americas; Latin American Drug Trafficking; Brazil’s Elections; Brazilian Politics; Anti-Americanism in Latin America; Mexico City; and The Guatemala Inoculation Experiments.

Alarcón, Benigno, Ángel E. Álvarez, and Manuel Hidalgo. 2016. "Can Democracy Win in Venezuela?" Journal of Democracy 27 (2):20-34.

Corrales, Javier, and Michael Penfold-Becerra. 2011. Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chávez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Ellner, Steve. 2008. Rethinking Venezuelan Politics: Class, Conflict, and the Chavez Phenomenon. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Ellner, Steve, and Miguel Tinker Salas. 2007. Venezuela: Hugo Chavez and the Decline of an "Exceptional Democracy". Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Hausmann, Ricardo, and Francisco Rodríguez, eds. 2014. Venezuela Before Chávez: Anatomy of an Economic Collapse. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Hawkins, Kirk A. 2010. Venezuela's Chavismo and Populism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCoy, Jennifer L., and David J. Myers, eds. 2004. The Unraveling of Representative Democracy in Venezuela. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Trinkunas, Harold A. 2005. Crafting civilian control of the military in Venezuela: a comparative perspective. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Velasco, Alejandro. 2015. Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela. Berkely: University of California Press.