The situation in Yemen has been described as the worst humanitarian disaster in the world. And it has taken that human catastrophe for many people to become aware of the small country that hugs the bottom of the Arabian Peninsula. But as Asher Orkaby explains this month, the current conflict has deep roots in how Yemen emerged as a nation, its treatment under British rule, its role during the Cold War, and now as a proxy for tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The fractures within Yemen make this humanitarian crisis one of the most complex to solve.

“Yemen is so advanced that even its government works remotely!”

As the civil war in Yemen continues to inflict heavy losses on the civilian population, precipitating an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, the country’s youth have turned to political humor as a coping mechanism.

In this instance, the joke is not far from the truth. Yemen’s internationally recognized government is sitting comfortably in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 900 miles away from Yemen’s capital city of Sana’a, while their host government continues a relentless bombing campaign and blockade targeting the 28 million Yemenis left behind.

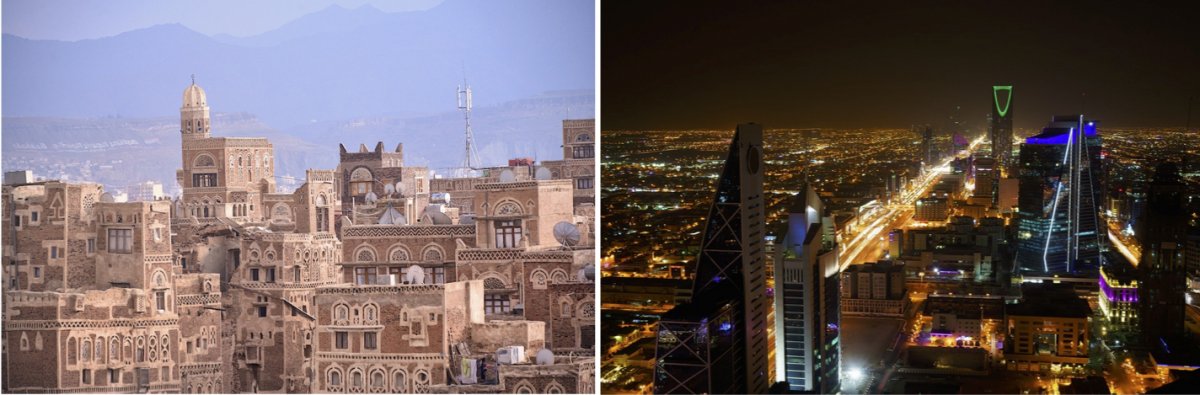

Sana’a, Yemen in 2013 (left) and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in 2019 (right).

International mediation has failed to bring the warring parties closer to a resolution, as efforts led by a succession of three UN Special Envoys have produced little more than fodder for political humor. An estimated $4 billion in annual humanitarian aid have reportedly been insufficient to eliminate the cholera epidemic or dispel warnings of impending mass starvation.

The increasing amounts of humanitarian aid, calculated at more than $142 per person, have only served to exacerbate the local conflict by creating a massive wartime economy and benefiting a select group of powerful individuals at the expense of the population most in need. Foreign aid is now ranked among Yemen’s most valuable “natural” resources, providing little incentive for reconciliation, as battles for the control of aid networks are sometimes fiercer than fighting for actual territorial control.

Villagers in Hajar Aukaish, Yemen searching rubble after a bombing in 2015 (left). Aerial bombing of Sana’a in 2016 (right).

How and when did the situation in Yemen collapse to such an extent?

As some journalists have reported, the war between the deposed government of Abd Rabu Mansur Hadi and the northern Houthi tribal organization traces back to September 2014 when Houthi tribesmen first entered Sana’a.

In the months following, Hadi and his closest political allies were placed under virtual house arrest as the Houthis pressured the central government for political concessions allotting equal political power to the country’s northern regions. Hadi’s desperate escape from Sana’a, first to the southern Yemeni port of Aden, and then by ship to Saudi Arabia, set the stage for a Saudi intervention ostensibly to defend the legitimate Yemeni government in exile.

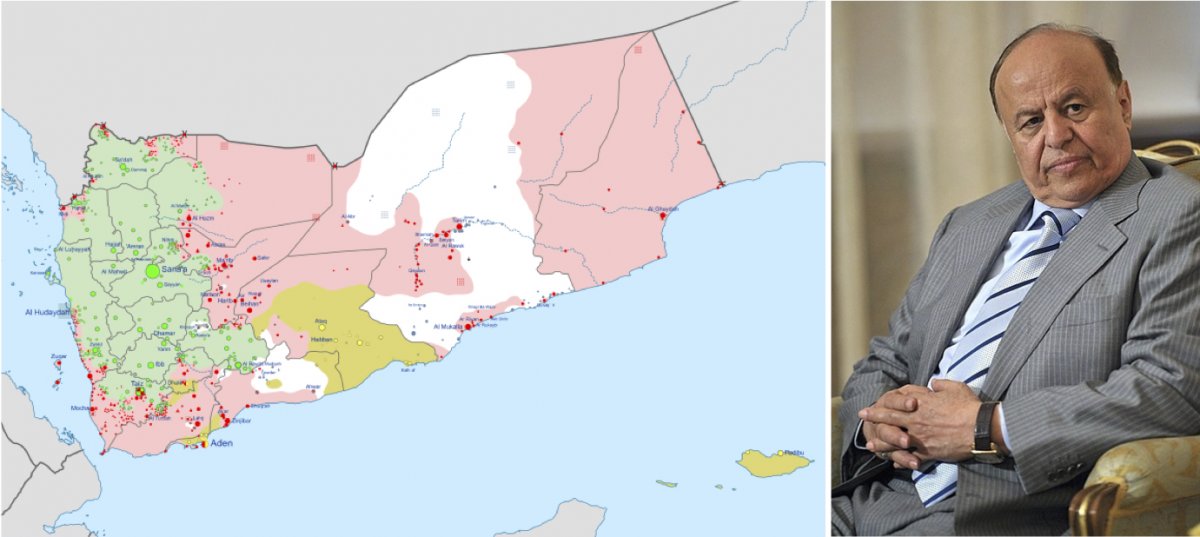

A territorial map of Yemen from 2018 with Houthi areas in green (left). Abd Rabu Mansur Hadi in 2013 (right).

A deeper look might find the roots of the civil war in 2011 when the Arab Spring protests first broke out in Yemen. These led to the resignation of longtime President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Even after a National Dialogue Conference brought together religious and social groups from across the country, the transitional government failed to produce a new constitution that would placate the most vocal opposition to the government in Sana’a.

In particular, Yemen’s northern population reacted virulently to the proposal to divide the contiguous northern region into three provinces as part of a new federalist state and the plan was a central grievance of the Houthi movement.

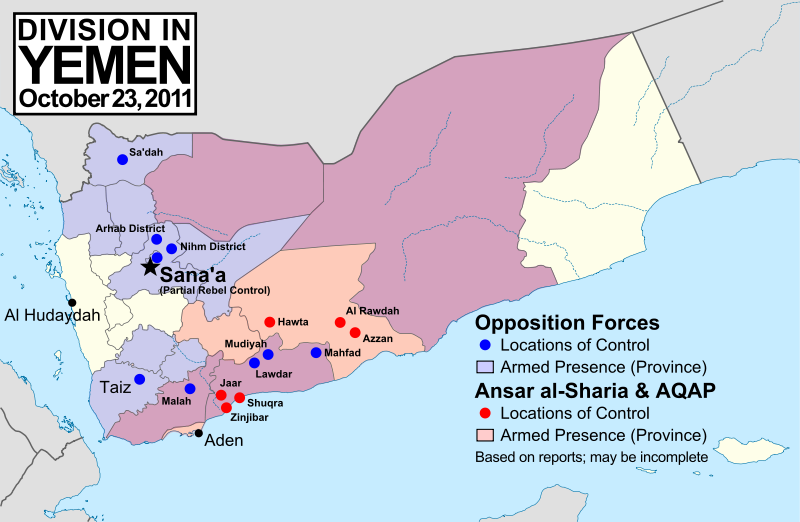

A map of Yemen’s divisions and areas of control in 2011.

Yemen’s northern highlands have been united for centuries by common religious beliefs, tribal alliances, and a history of independence from colonial domination. The transitional government’s proposal to split this historically unified half of the country, while also blocking it from accessing the Red Sea, struck a nerve among a prideful tribal population.

Other analysts might venture even further back in history to 2004, when the first of six wars between the Yemeni government and the Houthi movement began.

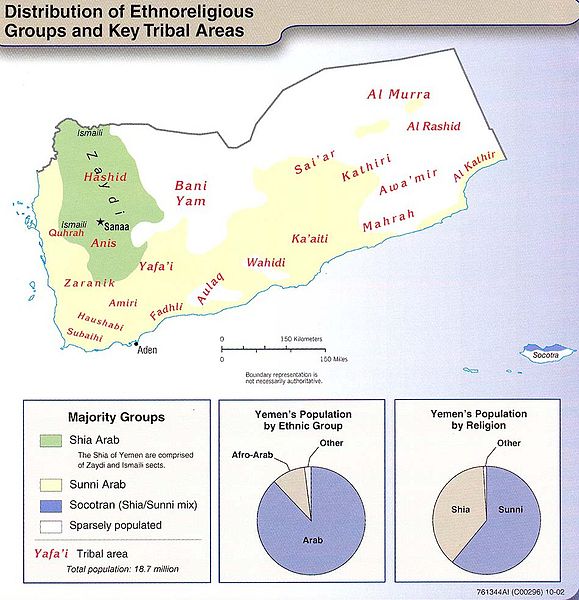

A map and graphs showing the distribution of religious and ethnic groups as well as tribal areas.

Alternatively, one could trace the origins of the current conflict to the 9th-century arrival of Zaydi Islam in Yemen and the gradual emergence of a class of religious and political elites, the descendants of whom are currently leading the Houthi movement.

A more manageable historical origin narrative begins in September 1962, at the contentious founding of the modern Yemeni republic. Its creation upended the status quo that had dominated South Arabia for more than 1,000 years, pitting a new generation of revolutionaries against a staunchly conservative religious and tribal class.

President Ali Abdullah Salal celebrating the founding of the Republic of Yemen in 1962.

The original conflicts that precipitated the country’s first civil war during the 1960s remain at the core of the current conflict between the Houthi movement and the Republic of Yemen. Resolving this war will require not only a temporary cessation of hostilities, but also a more complete reevaluation of the Yemeni state.

The Famous Forty and the Birth of Modern Yemen

The Arab Spring protests that broke out across the region arrived in Yemen in February 2011, as a disaffected youth population took to the streets to protest presidential nepotism, high unemployment, corruption, and public infrastructure that scarcely benefited from government oil revenue. The months of protest were highlighted by moments of violence and bloodshed. When dozens of protesters were killed in March 2011, civil disobedience was accompanied by attacks in retribution, culminating with the bombing of Saleh’s presidential mosque in June 2011.

Yemeni protesters in August 2011 (left). Protesters marching to Sana’a University in March 2011 (right).

Although Saleh was wounded in the attack and needed to travel to Saudi Arabia for medical care, it was not for this reason that both sides of the street protests took pause.

Among the unintended casualties in the assassination attempt was ‘Abd al-Aziz ‘Abd al-Ghani, one of the republic’s founders and a political leader well respected by all strands of Yemeni society, who had been praying next to Saleh at the time. The pause in protests and violence was a recognition of not only the passing of a great leader, but also the passing of an entire revolutionary generation, of which ‘Abd al-Ghani was one of the last.

Protesters calling for President Saleh to resign in February 2011.

For nearly 1,000 years until 1962, Yemen was dominated by Sayyid families—direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad—and ruled by an imam, or religious leader, who controlled the country’s northern highlands and western coast through a loose coalition of tribes and militias.

The construction of a modern Yemeni republic began during the 1930s when Imam Yahya, the ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of North Yemen, financed a study abroad program for 40 of the country’s most talented youth. Most of these students attended military colleges in Egypt and Iraq, while others pursued advanced degrees in Europe and in the United States.

Imam Yahya envisioned this group, known in the Yemeni historical record as the Famous Forty, as his administration’s future leaders in the military, politics, and industry. Nearly all the students, including ‘Abd al-Ghani, returned to Yemen to constitute the core of the country’s civil service for the subsequent seven decades.

This initial group of students was soon followed by hundreds of Yemeni youth who took advantage of local networks of support to study abroad and returned home to occupy important roles in public and private industry. They also helped develop Yemen’s nascent healthcare and service sector.

Much to the chagrin of Imam Yahya and his son Ahmad, the Famous Forty returned home with far more than a superior education. Few of them were content with the imam’s repressive rule, the lack of domestic infrastructure, or the dearth of opportunities for economic and social advancement.

Imam Ahmad in 1946 (left). Imam Muhammad al-Badr in the mid-1960s (right).

The assassination of Yahya in 1948 and a failed attempt to install a replacement imam was followed by multiple attempts on the life of Imam Ahmad until his death in September 1962. Seven days after Ahmad’s funeral, a republican movement led by the alumni of Yemen’s Famous Forty succeeded in overthrowing the last Imam, Muhammad al-Badr. These founding fathers etched their place as immortal heroes in the history of the Yemeni republic.

As the members of this initial revolutionary generation have passed on, Yemen’s once entrepreneurial and relatively well-trained civil service has not been replaced by a similar cohort of youth dedicated to the success of their country. Instead, political appointments since the 1990s have been used largely to grow a network of nepotism and crony capitalism.

Abdullah Salal in the center with the heads of the coup in 1962 (left). Salal at a military parade in 1963 (right).

Rather than return home to serve their country, educated Yemenis have become disillusioned with the lack of employment opportunities in Yemen and have increasingly elected to remain abroad. This nationwide “brain drain” has left the country with a declining system of education and administration. Without the legitimacy provided by the revolutionary generation, fissures within the republic have reached the very foundations upon which the state was founded in 1962.

The Houthi Movement

The Houthis are a prominent family in Yemen’s northern highlands formerly led by Badr al-Din al-Houthi, the family’s deceased patriarch, a well-respected religious scholar and a Sayyid.

When a republic was declared on September 26, 1962, the institution of the imamate was dissolved, precipitating eight years of a bloody civil war that led to the eventual economic and political marginalization of tribal leaders and the centralization of state control in Sana’a. The traditional hierarchy that placed Sayyid families at the pinnacle was replaced by a republican system that preached social equality and allotted political power according to a presidential patronage network rather than family of birth.

The Yemeni Prime Minister, Prince Hassan, meeting with tribesmen in Wadi Amlah, Yemen in 1962.

First known as Ansar Allah, or Supporters of God, the grassroots Houthi movement began as a religious revivalist program during the 1990s. Saudi proselytization of a more conservative Salafi interpretation of Islam threatened to undermine the traditional Zaydi religious sect unique to Yemen, practiced by approximately 40% of the country’s population.

Under the stewardship of Hussein al-Houthi, the Zaydi revivalists formed a political party that produced few tangible results, before transforming into a populist front outside the confines of the national Yemeni government.

An image of Hussein al-Houthi at a protest over Saudi-led airstrikes in 2015.

Hussein’s slogan “death to America, death to Israel, curse upon the Jews, victory to Islam” spread like wildfire throughout the Zaydi mosques and religious schools, highlighting an association between the hated regime of Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh and growing anti-American sentiments across the Middle East.

Zaydi religious opposition to the Yemeni republic was perceived as a threat to Saleh’s regime and eventually led to a clash of arms between Houthi family supporters and forces led by Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, the boyhood friend of Saleh and a Salafist by faith.

In 2004, after the first of six battles, republican military forces killed Badr al-Din’s son Hussein al-Houthi, thus making him a martyr for the Zaydi religious cause and posthumously lending his family name to the movement.

Ali Abdullah Saleh and the Unification of Yemen

After his assassination by Houthi tribesmen in December 2017, gruesome images of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s corpse were broadcast widely across news outlets and social media. The images were followed by hundreds of obituaries conveying contrary opinions of this cunning politician whose 33-year presidency had come to define the modern state of Yemen.

When Saleh first inherited the presidency in 1978 following the assassination of two predecessors, few expected him to last to the end of the year. He certainly was not expected to craft one of the longest terms of office in the Middle East.

At his core, Saleh was a true Yemeni nationalist, a persona exhibited at the age of 12, when as an orphaned child he lied about his age in order to join the army. His true test of strength occurred during the 1968 Siege of Sana’a when Saleh was among the capital city’s last heroic defenders, withstanding a tribal assault and saving the republic.

This display of bravery earned Saleh multiple promotions and an early start to a political career where his penchant for inspiring oration, constructing alliances, and engaging in corrupt politics became apparent. In what he often termed “dancing on the heads of snakes,” Saleh managed to balance rival tribal, religious, and political factions and maintain his presidency within a sea of dissenters.

Ali Abdullah Saleh (center) at a unification ceremony for North and South Yemen in 1990.

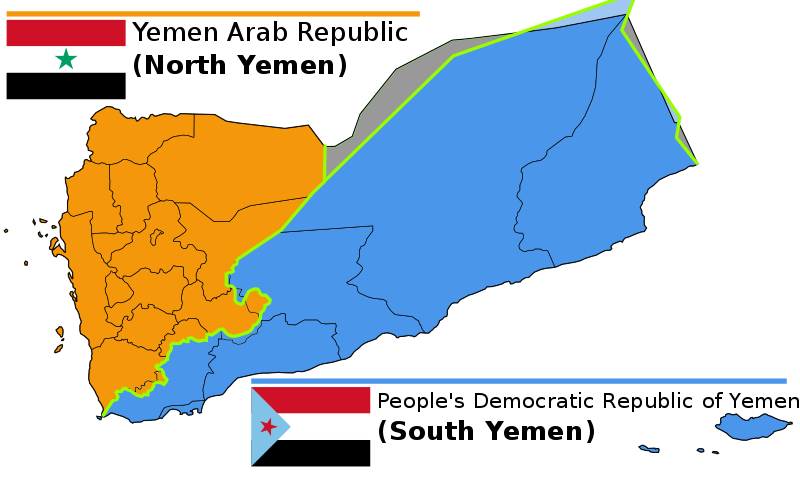

This dance reached its crescendo with the 1990 unification of North and South Yemen, which had been divided for centuries by different linguistic dialects, religious sects, economic structures, topographies, and recent colonial histories.

While North Yemen remained a semi-autonomous religious dominion under the remote suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire, South Yemen had been occupied by the British Empire since 1839. The southern Yemeni port of Aden gradually became a colonial epicenter in the region while the surrounding hinterland was organized under a unified British Protectorate.

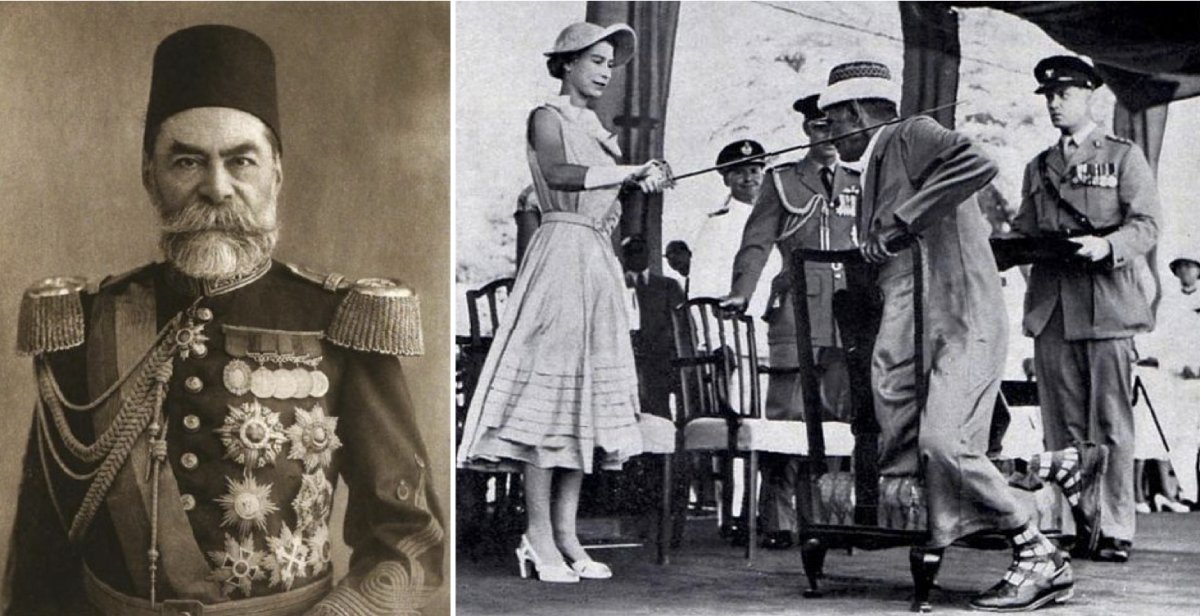

Ahmed Muhtar Pasha, the Ottoman Grand Vizier of Yemen, in 1912 (left). Queen Elizabeth in Aden, Yemen knighting Sayyid Abubakr in 1954 (right).

After a contentious struggle for independence during the 1960s, British colonial forces withdrew, leaving radical Marxist groups to form the first and only Arab communist state by 1968. Aden became a naval base for the Soviet Union and multitudes of international terrorist organizations sought refuge in South Yemen.

Relations between the two Yemens were punctuated with episodes of cross-border violence as local differences were exacerbated by the global conflict of the Cold War.

A map depicting North and South Yemen before unification in 1990.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen lost its principal sources of foreign aid, precipitating the rapid collapse of the state’s generous social benefits, education, and healthcare. Sensing an opportunity for political consolidation, Saleh arranged a hasty union between North and South, granting southern leadership an equal share of political seats despite the relatively smaller population.

The newly unified Yemen had the misfortune of being selected to represent the Arab World on the UN Security Council in 1990, on the eve of the First Gulf War. Yemen’s decision to support Iraq and object to the U.S.-led motion to condemn Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and sanction a coalition force against Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait proved costly. Within 24 hours, the United States rescinded foreign aid to Yemen and Saudi Arabia expelled nearly a million Yemeni migrant workers whose families depended upon their continued remittances.

The return of a million unemployed Yemenis and the loss of one of the country’s most significant sources of revenue sent the Yemeni economy into a tailspin culminating in yet another civil war in 1994.

When Yemen held its first free elections in 1993, the Yemen Socialist Party, led by South Yemen’s leadership, performed poorly and finished third behind Islah, a new Islamist party that recruited new members from among those most severely impacted by the economic hardships that followed the First Gulf War.

When the south seceded from the union in 1994, Saleh relied upon these same Islamists, many of whom had returned home after fighting the Soviet Union as jihadists, or holy warriors, in Afghanistan. The southern secessionists were defeated after Islamist fighters sacked the port city of Aden. Southern nationalism was temporarily derailed, but was rekindled again in 2007 in the form of al-Hirak, a new political party that revived the southern flag, protested northern grievances, and called for southern autonomy.

The flag of South Yemen used today by the political party al-Hirak.

In the last years of Saleh’s presidency, his administration in Sana’a was flanked in the south by al-Hirak, in the north by the Houthis, and in his own capital city by the public protests of the Arab Spring.

When Saleh resigned in February 2012, the metaphorical snakes exposed their poisonous fangs and began pulling down the foundations of the republic. Even Saleh’s surprising decision to ally with the Houthi family, his former enemy, did little to forestall his demise as he was killed before ever having a chance to once again become Yemen’s kingmaker.

Saudi Arabia and Yemen

The origins of Saudi policy in Yemen date back decades and are the key to understanding the current crisis.

Shortly after the founding of Saudi Arabia in 1932, King Ibn Saud sent an emissary to the Yemeni Imam Yahya proposing the settlement of a boundary issue. Yahya rejected the emissary with the now infamous line: “Who is this Bedouin coming to challenge my family's 900-year rule?”

King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia and Imam Ahmad of Yemen (c. 1950s).

In the ensuing war, Yahya’s tribesmen were soundly defeated, and Ibn Saud captured three territories along the border: Asir, Najran, and Jizan. The 1934 Treat of Ta’if made this annexation official while also setting the stage for a perpetual Saudi-Yemeni territorial rivalry.

Securing the southern border subsequently became a Saudi priority, especially during moments in history when threats from Yemen seemed particularly alarming. During the 1960s, when Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser stationed 70,000 Egyptian troops in Yemen in support of the new republic, his open threats to the royal family drew Saudi Arabia into the civil war in support of the deposed Imam Muhammad al-Badr.

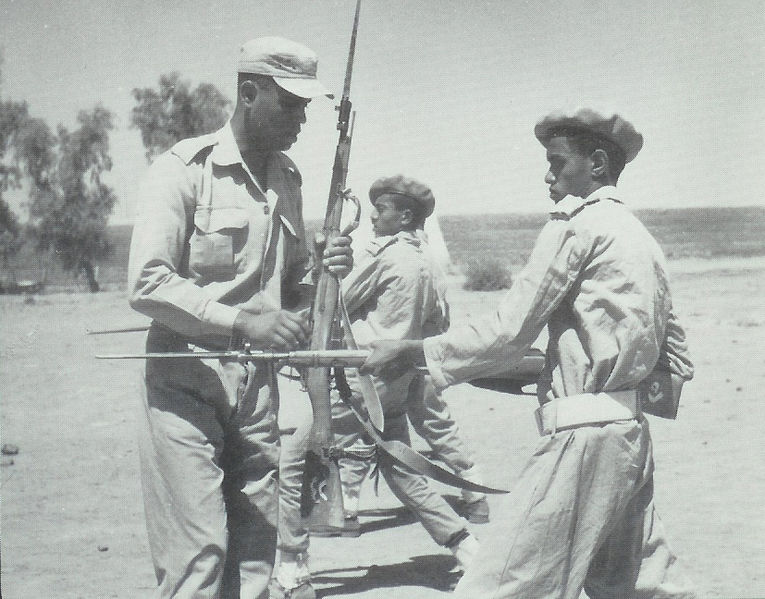

An Egyptian soldier showing a Yemeni recruit how to use a bayonet in the 1960s.

Yemeni nationalism, in particular, served as a potent warning sign for Saudi Arabia, who feared that a more populous and centralized Yemeni state might demand the return of the three provinces and embark on a military expedition that could threaten the monarchy. Similarly, following the 1990 unification of Yemen, Saudi Arabia was concerned that a unified Yemen could destabilize the region and was one of the only countries to support the southern secessionists during the 1994 civil war.

After securing a renewed territorial agreement in 2000, Saudi Arabia moved to restrict freedom of movement across the southern border. The construction of a new border wall and an increased number of border guards severed historic trade routes and separated families and tribes living on both sides of the border.

As the Houthi movement began to coalesce, concern grew about the sizeable rebel group forming along the border between the two countries, convincing the Saudis of a need to insert ground forces into Yemen in 2009.

The death of dozens of Saudi soldiers in battle with Houthi tribesmen marked the first and possibly last time that Saudi troops would engage with the Houthis in the mountainous territory of Yemen’s northern highlands. The casualties served as the basis for the Saudi army’s mantra exchanged in jest: “Staying in cool places and avoiding the sun … and staying away from the Yemeni army!”

When the Houthis seized the capital city of Sana’a, the movement’s leadership used the pulpit to declare their malicious intentions against Saudi Arabia, thus precipitating yet another round of the ongoing Saudi-Yemeni rivalry that began in 1932.

Purportedly at the behest of Mansur Hadi, Yemen’s president in exile, the Saudis continue to lead a coalition of regional states against the Houthis in Operation Decisive Storm, later paradoxically renamed Operation Restoring Hope.

The aftermath of Saudi bombings in Sana’a in 2015.

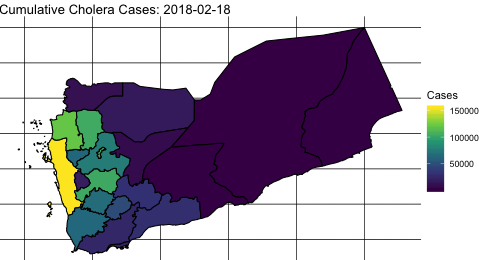

The Saudi bombing campaign, bands of mercenary ground forces, and a merciless naval and air blockade have precipitated what analysts refer to as one of the worst man-made humanitarian crises of modern times. Alarming statistics detailing the number of cholera victims in Yemen, coupled with shocking photos of starving children, have led Western countries to condemn the Saudi campaign and struggle to understand the ultimate goals of these operations in Yemen.

Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman portrays his support for the war in Yemen as acting on an official UN condemnation of the Houthi movement and as ultimately constituting a safeguard against Iranian expansion in the region.

A map showing the extent of the cholera outbreak in 2018.

A Fragmented Country

The ongoing war in Yemen is not a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran as is sometimes asserted. Nor is it a religious war between the Sunni and Shi’i sects of Islam. Rather this is a unique moment wherein the Yemenis must decide the future of their country.

The civil war that began in 2014 between the northern population and the republic can be seen as a continuation of the country’s first civil war between a traditional, religious, and tribal society from the northern countryside and a republic led by an educated and urban elite.

The secession of hostilities in 1970 can, in retrospect, be seen as only a temporary truce that resulted in the marginalization of the defeated northern highlands. The children and grandchildren of those same defeated tribesmen who had supported the deposed Imam al-Badr, have now returned to the capital city of Sana’a demanding political retribution and remaining undeterred by a republic bereft of its revolutionary legitimacy.

A map of the conflict in North Yemen between Republicans (black) and Zaydi Royalists (red) in 1967 (left). Anti-Houthi protests in Sana’a in 2017 (right).

The republic founded in 1962 has since dissolved, leaving in its wake unresolved grievances and competing aspirations for independence within South Arabia. History has shown that neither two separate Yemeni states nor one centralized state can foster long-term stability for the region.

Rather, a decentralized federalist state that provides equal degrees of autonomy and resource sharing to southern separatists, northern Houthis, and other traditionally independent regions in Yemen might form the foundations of a future Yemeni state—one that will both assuage Saudi fears of a strong Yemeni state and provide political and economic opportunity to a new generation of Yemeni leadership.

Throwing money at the problem will not immediately solve the crisis, nor will it ensure the long-term stability of South Arabia. Rather than isolate Yemen as a pariah state, the wealthy Gulf countries would benefit from incorporating 28 million Yemenis into the Gulf economy, alleviating border tensions, and empowering Yemenis to chart their own paths.

Read more on the Middle East: Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Religious Divide in Iraq; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; Feminism in Egypt; the Alawites and Syria; Turkey’s Politics; ISIS; U.S.-Iraq Relations; and The U.S. War in Iraq.

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East; Women in the Mideast and North Africa; and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

Brandt, Marieke. Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict. London: Hurst & Co. Publ. Ltd., 2017.

Caton, Steven Charles. Yemen Chronicle: An Anthropology of War and Mediation.New York: Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

Dresch, Paul. A History of Modern Yemen.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Haykel, Bernard. Revival and Reform in Islam: The Legacy of Muhammad Al-Shawkānī. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Orkaby, Asher. Beyond the Arab Cold War: The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-68. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Phillips, Sarah. Yemen and the Politics of Permanent Crisis.New York: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2011.

Vom Bruck, Gabriele. Islam, Memory, and Morality in Yemen: Ruling Families in Transition. 1st ed. ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.