On March 3, 1913, the day before President-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, more than 5,000 women—young and old, rich and poor, educated and non-educated, (though mostly white)—marched down Pennsylvania Avenue to demand the right to vote. It remains the largest suffrage event in U.S. history. These women hoped to attain the vote during Wilson’s administration, and indeed they did.

Women suffragists marching on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C., March 3, 1913.

On January 21, 2017, 104 years and 26 presidential elections later, once again thousands of women will assemble in Washington, D.C. to draw a new President’s attention to women’s rights. As the 2017 Women’s March on Washington approaches, the 1913 Suffrage Parade offers some important lessons.

For starters, the planners of the 1913 march had their organizational act together. Communicating via a federated national organization called the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and led by recent college graduate Alice Paul, age 28, a handful of women working out of a ramshackle office at 1420 F Street, NW organized a hugely successful public and media spectacle.

Suffragist and women's rights activist Alice Paul, c. 1920.

In two months’ time, they raised nearly $15,000 (approximately $360,000 today); transported and housed thousands of women from around the world; secured multiple permits for the parade and related pageant, rally, and open air meetings; built, decorated, and executed a stunning parade that included 24 floats and nine bands; and ran a top-notch press office that placed favorable stories in newspapers across the country. The 1913 parade made it clear that women were a political force to be reckoned with.

But a parade “of fine dignity, picturesque beauty, and serious purpose” was just the window display for much grander plans. These women played the long game. Their ultimate goal was to re-energize the sixty-five- year-old suffrage movement and pass a suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. While in D.C., suffragists made themselves heard to elected officials using methods that seem quaint and exhausting today—methods with which we might want to reacquaint ourselves.

In the months leading up to and following the parade, the suffragists circulated petition after petition, regularly lobbied their Congressional and state representatives, befriended Congressional and White House staff, mastered Congressional procedures and cleverly worked within them, and cultivated such strong relationships with President Wilson that he changed his mind about women voting.

The organizers of the 1913 parade accomplished all this in the face of obstacles that those of us alive today can scarcely imagine. They began with a fundamental paradox: they were trying to convince elected officials that women deserved the vote when the main way to influence office holders is through voting. In addition, while NAWSA counted over 200,000 members by the 1910s, the majority of Americans—male and female—still opposed the vote for women. Most painfully for suffragists, many of these “antis” included their own husbands, siblings, children, friends, and neighbors.

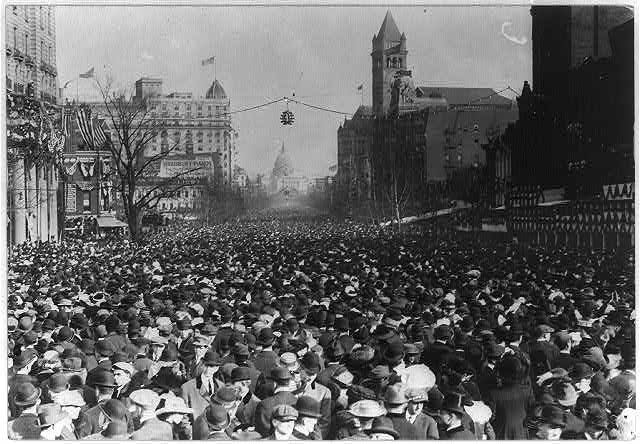

Crowds block the path of the Woman Suffrage Procession, March 3, 1913.

Public opposition to women voting reached a crescendo during the 1913 march. The procession was scheduled to begin at 3 pm, but protesters blocked Pennsylvania Avenue and the women waited for police to clear the street. By 4 pm, the women had barely made it one block. With every step, mobs of angry men jeered at them, pushed them, and threw bottles and trash at them. Over one hundred women had to be taken to local emergency rooms. The crush of the crowd was so intense that one observer likened police attempts to clear even a single file line for the parade to “the efforts of a man to stop a waterfall by using first one hand and then the other, and thinking to stop it in that way.” When it seemed that the police had joined forces with the male protesters, the cavalry was called in. Undaunted, these savvy women used the parade’s disruption to generate countless media stories and goodwill.

The Suffrage Parade surrounded by crowds at 9th Street, March 3, 1913.

Washington was thoroughly segregated in 1913 and Alice Paul and her colleagues debated whether to include black suffragists in the march. Publicly, they said they feared Southern delegations would pull out of an integrated parade; privately, many shared the dominant ideology of the Jim Crow era. Ultimately, Paul suggested that black women march at the very end of the parade, an edict that anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells flouted when she marched alongside the Illinois delegation.

Perhaps most effectively, Paul used the success of the 1913 parade to reach out to women around the country and enlist them in her effort to pursue a Constitutional suffrage amendment, to set up a fully-staffed DC office, to jumpstart a new suffrage newspaper focused on DC lobbying efforts, and to continue public protests as suffrage strategy. Paul’s bold tactics caused a schism with the NAWSA and led her to establish the National Woman’s Party. This fractured the women’s movement, but having an adversary reinvigorated NAWSA and increased the group’s lobbying power.

The 1913 Parade marked a turning point in the women’s suffrage movement. It introduced a new generation of leaders, turned lukewarm adherents into passionate activists, reinvigorated the national organization, and made women’s rights front-page news. In the months before and after the parade, Members of Congress, even those who opposed women voting, took notice and, for the first time, treated women as real constituents and citizens. President Wilson disdained Paul, but her protests forced him to grapple with suffrage—and he ended up working very closely with NAWSA leaders to forcefully advocate for the federal suffrage amendment.

Women suffragists picket in front of the White House, 1917.

In the 1916 election, Paul encouraged the ten million women who could vote—those enfranchised in the western states—to oust Democrats in protest of the party’s failure to act on suffrage. The nonpartisan NAWSA disavowed this strategy. But, in 1918 after the suffrage amendment failed to pass the Senate by two votes, NAWSA worked to defeat key opponents. With a new Congress in place, the 19th Amendment passed both Houses of Congress in 1919. NAWSA became the League of Women Voters and the National Women’s Party shifted focus to the Equal Rights Amendment.

Two suffragists showing banner to young girl, c. 1910-1920.

Since the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, women have struggled to rally around a single issue or platform like suffrage. The Women’s March on Washington is the closest I have seen to a national movement of women in my lifetime. The suffragists who paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in 1913 successfully paired awareness-raising public spectacles with savvy legislative strategizing and good old-fashioned political activism. They teach us that marching is powerful, but only when linked to organizing, lobbying, voting, and electing those who represent the interests of women. While I look forward to the success of the Women’s March on Washington, I am even more excited to see how the movement develops after January 21st.