Few things are more expensive than housing. The purchase of a home is the single greatest expense in most people’s lives. For non-homeowners, rent usually takes up the largest share of the paycheck. The astronomically high real estate prices in Silicon Valley (where even people with six-figure incomes may qualify for housing subsidies) have attracted media attention, but they are only the most recent manifestation of an ancient problem. In his 1872 essay on “the housing question,” Friedrich Engels examined the wretched dwellings of the working class under capitalism, noting a troubling contradiction: shelter is a fundamental need, but in a market system there’s a cost to it. For poor people that cost is often too high. For millennia, people have wrestled with this dilemma. In economically stratified societies—that is, almost everywhere—how can the poor find shelter? How have societies solved this basic problem? Why have they adopted certain solutions, and then abandoned them almost immediately? And what has happened when the poor have taken matters into their own hands?

1. The York Almshouse

The almshouse at Woburn, Bedfordshire, England

The first home for the poor in England was established around 936 CE by King Athelstan. Its location was York, once a Roman fortress and by the Middle Ages an important commercial center. As the city grew, so did its population of poor residents—the elderly and the injured, widows and children. In medieval Christianity, it was the responsibility of the devout to help the poor in their midst by giving alms, usually in the form of food or money. But Christian charity could not keep up with the increase in poverty in York, especially as the city suffered from repeated battles between Vikings and the English. After a decisive victory over the Vikings, King Athelstan traveled through York, and, according to legend, was moved by the sight of the poor sleeping in the streets. He endowed an almshouse on royal land, a place where the poor could be housed. Nothing remains of it today, but it was the first of thousands of almshouses built throughout England.

2. Praying for Bankers’ Souls: The Fuggerei

The Fuggerei, Augsburg, Bravaria

The wealth of billionaires today pales in comparison to the fortune created by the most important pioneer of early capitalism: Jacob Fugger of Augsburg, the financier of the Habsburg Empire, banker to the Vatican, and trader known appropriately as Fugger “the Rich.” His astounding wealth clashed with a society in which most people were desperately poor, offending Christian virtues and leading Martin Luther to rail against the “verdammte Fuckerei”—the damned Fuggers. Resentment grew when the Pope, at the behest of Fugger, lifted the church’s ancient proscription of usury and legitimized the collection of interest on loans.

When the church began the sale of indulgences, largely to repay a loan to Fugger, popular outrage led to the Protestant Reformation. In this tense moment, Fugger founded a new kind of housing complex, built between 1514 and 1523, known as the Fuggerei. The Fuggerei differed sharply from previous housing for the poor. Much larger than the typical almshouse, the Fuggerei consisted of 52 separate homes, which together could house hundreds of residents. And unlike an almshouse, the Fuggerei was intended for the “deserving poor,” those who worked but in spite of their labor could not afford housing. The rent was one Rhine guilder per year (half the city’s average) and three prayers per day for the soul of Jacob Fugger. Whether created out of a sense of social obligation or to forestall criticism, the Fuggerei represents a shift in the history of housing the poor. The Fuggerei still exists, and the rent remains one Rhine guilder—roughly one U.S. dollar—a year.

3. The Victorian Workhouse

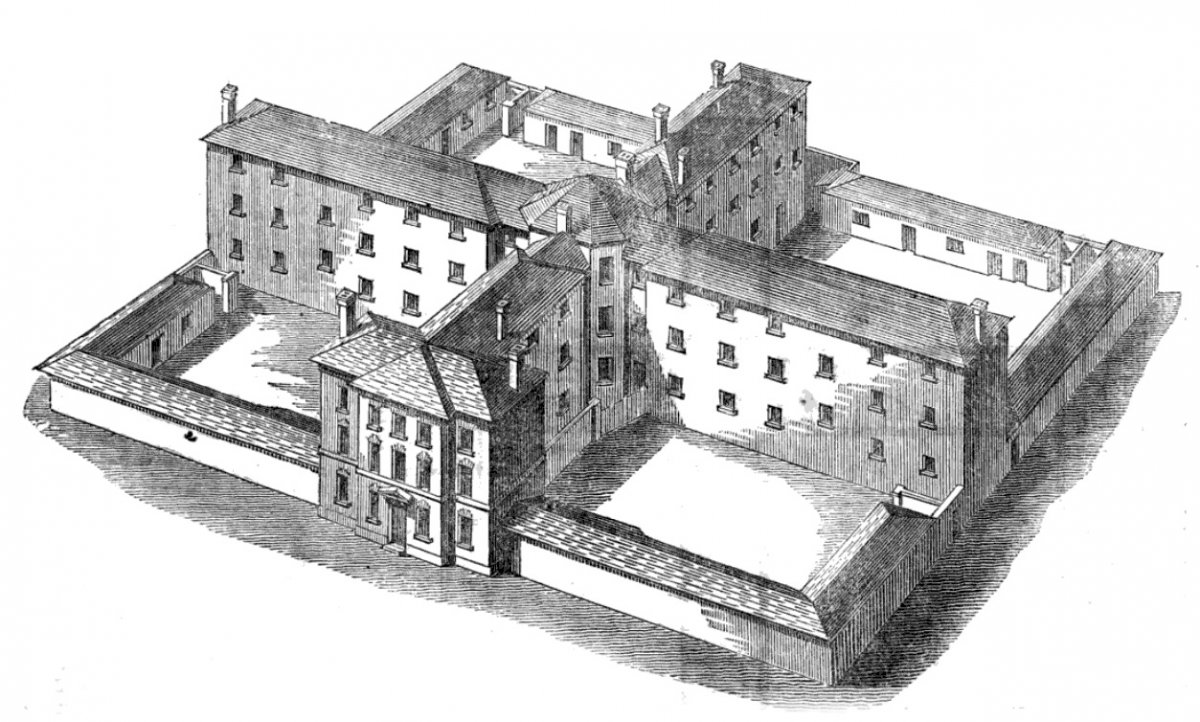

An 1834 cruciform design workhouse for 300 people

The Industrial Revolution created a housing crisis for the poor, and nowhere was this more pronounced than the Industrial Revolution’s birthplace, England. Concerned about growing numbers of paupers that accompanied industrialization, the English Parliament passed the New Poor Law of 1834. The law created a new era of workhouses. Although its creators had the best of intentions, the Victorian workhouse became a brutal, almost penal system depicted by Charles Dickens as a kind of hell. The Victorian workhouse was designed like a prison. Upon admission, families were separated. Inmates performed dangerous and sometimes pointless work (breaking rocks by hand, unwinding the fibers of old ropes, crushing bones for fertilizer).

Life was severely regimented. Inmates wore uniforms and lived by a strict clock. Meals were taken in enforced silence, and the gruel sometimes kept the inmates only barely from starvation—hence Oliver Twist being famously punished for saying, “Please, sir, I want some more.” As Dickens’ story suggests, the poorhouse was particularly hard on orphans. The punitive system allowed for no resistance. Hundreds of thousands of paupers lived in the workhouses. In their scale, discipline, and arduousness, the Victorian workhouses mark a shift in housing the poor from the earlier models based on Christian charity.

4. Huddled Masses Yearning to Breathe Free: The Manhattan Tenement

Manhattan's Lower East Side Tenements

In the United States, industrialization brought migrants from all over the world, many of whom crowded into New York. In the late 19th century, Manhattan was the most densely populated city in the world. More than 300,000 people lived in a single square mile of the Lower East Side. Such density was made possible by a new kind of housing: the tenement.

Tenements were large buildings, typically five or six stories high, that filled almost all of the available land. The only outdoor spaces were an outdoor toilet, shared by hundreds of people, the fire escapes, where residents relaxed and socialized, and the roofs, where many people slept. The buildings were packed with people, often 16 to a room, and only the outermost rooms had direct access to sunlight and fresh air. A single block of tenements might have 600 apartments, together housing more than 4,000 people. To improve living conditions, reformers in 1879 introduced the “dumbbell” tenement, a design intended to bring more fresh air through regularly placed airshafts. Yet conditions scarcely improved, and by the 1890s, three-fifths of the city’s residents lived in tenements.

Most of the residents were immigrants, a diverse mixture of Irish, Germans, Italians, and Russian Jews. Looking at the tenements, one critic saw “a seething mass of humanity, so ignorant, so vicious, so depraved that they hardly seem to belong to our species. Men and women; yet living, not like animals, but like vermin!” With such residents, he continued, “it is almost a matter of congratulation that the death rate among the inhabitants of these tenements is something over fifty-seven percent, and the mortality among the children under five years of age is… as high as seventy percent.” The poverty of the tenements was captured by one of the first muckraking photographers, Jacob Riis, in How the Other Half Lives. Riis’s pictures of crowded, bleak rooms made the tenement the icon of the urban slum.

5. Standardization and Functionalism: The Zeilenbau

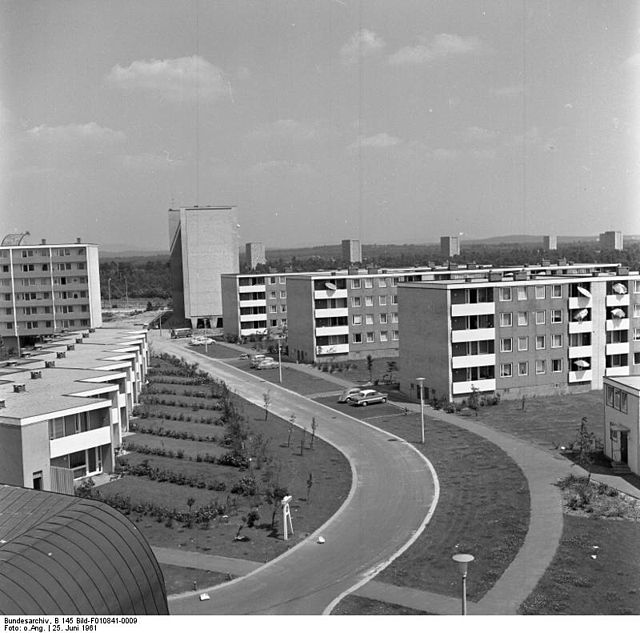

Zeilenbau in Nurnberg, Germany

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a new generation of reformers aimed to address what they saw as the evils of the industrial age. They launched an era of reform that stretched across the Atlantic. In Germany, the industrial era prompted new ways of thinking about housing the poor, embodied in the Zeilenbau, a style of housing projects built in the 1920s and 1930s. Designed by the Ernst May, Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius of the Bauhaus, and other celebrated architects of European modernism, the Zeilenbau consisted of long, rectangular buildings, surrounded by expansive lawns, oriented to provide their residents with abundant sun, light, air, and open space. Each building contained dozens of identical apartments.

Reflecting the functionalist ethos of their creators, the Zeilenbau were little more than large concrete slabs with plate glass windows and no ornamentation. Inspired by American industrialists, particularly automaker Henry Ford and engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, the Zeilenbau were monuments to efficiency, standardization, and mass production. (Rotterdam architect J.J.P. Oud even called his housing projects “dwelling Fords.”)

Ostensibly egalitarian and democratic, the Zeilenbau were hailed as the solution to the problem of workers’ housing in the industrial era, but they were roundly disliked by the people who had to live in them. For residents, the mathematical precision of the Zeilenbau was cold, their uniformity oppressive. In spite of these critiques, the form of the Zeilenbau influenced the design of housing around the world.

6. Public Housing for All: Singapore

The Tiong Bahru housing estate, Singapore

Through its patterns of industrialization and urbanization, the North Atlantic nations of England, Germany, and the United States had developed certain ways of housing the poor. They exported these housing forms to rest of the world through colonialism. In 1927, the British established a housing agency in their valuable port colony of Singapore. The Singapore Improvement Trust aimed to address the crowding, squatting, and slums that plagued the island city.

Their first project was the Tiong Bahru housing estate, 30 apartment blocks with over 900 units built on a redeveloped cemetery that was inhabited by over 2,000 squatters. As a British creation, Tiong Bahru adopted European and American Art Deco styling, yet it adapted public housing for a tropical climate, where open windows and cantilevered balconies provided shade and air flow. Unlike American and European housing projects, Tiong Bahru intertwined residences with street-level shops.

While the construction of Tiong Bahru marks a milestone in public housing, the Singapore Improvement Trust had built only 23,000 units by the time Singapore gained its independence from the United Kingdom. With more than half a million residents living in squatters settlements or shophouses, the new government launched the world’s most ambitious housing plan, constructing unprecedented levels of public housing, largely in high-rise apartment complexes. Today, eighty percent of Singapore’s residents live in public housing. Likewise, in Hong Kong, another British colony, roughly half the population of 7 million lives in public housing.

7. Pruitt-Igoe

Pruitt-Igoe, St. Louis, Missouri

The iconic example of American public housing was St. Louis’s Pruitt-Igoe. Built in 1954, Pruitt-Igoe was a testament to modernism—33 nearly identical 11-story towers arranged in rows on 57 acres of land. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki, Pruitt-Igoe embodied Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s vision of the “tower in the park,” with high-rise towers leaving most of the grounds an open, grassy expanse.

Pruitt-Igoe replaced a neighborhood of “ramshackle old houses jammed with people,” in the celebratory words of Architectural Forum, with “vertical neighborhoods for poor people.” Reflecting standard practice at the time of its design, the project was racially segregated, with the Pruitt Homes intended for African Americans and the Igoe Apartments for white residents. But as it was completed, the Supreme Court banned this kind of segregation. Few white families moved in, and most of the project’s 2,870 apartments were inhabited by African Americans.

While early residents marveled at the prospect of living in a “poor man’s penthouse,” Pruitt-Igoe declined quickly and it was spectacularly demolished less than 20 years after it opened. The collapse of Pruitt-Igoe became a symbol of the failure of American public housing more generally. Its downfall was blamed on several culprits, from its vapid architecture to its poor residents. But the failure of Pruitt-Igoe was due to events beyond the project itself. As St. Louis underwent deindustrialization, disinvestment, and depopulation, Pruitt-Igoe declined as well. Public housing, however monumental in scale, was never commensurate with the public policies that created an urban crisis that beset cities across America.

8. A World of Homeowners: Ciudad Kennedy

On December 17, 1961, President John F. Kennedy went to Bogotá, Colombia, to lay the cornerstone for the Techo Housing Project. Surveying the sunny swath of land on the outskirts of the city, Kennedy declared, “This is a battlefield.” The surprising statement indicated that the Cold War was fought not only with missiles and guns but also with houses. And in this war, the U.S. had a secret weapon in its arsenal: government programs that promoted homeownership.

Indeed, wherever State Department cold warriors went, housing programs soon followed. Programs aimed to broaden homeownership, which would fight communism and promote capitalism as they lifted the world’s poor into the middle class. The Techo Housing Project (later renamed Ciudad Kennedy in honor of the president) was the largest housing project under the Alliance for Progress, Kennedy’s plan for economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America.

Yet it could not have been more different from housing projects in the U.S. It was designed as “self-help” housing, in which the government provided legal and financial assistance while families provided the manual labor to build their own homes. In the end, few poor people were able to take advantage of the program, since they lacked the minimum income necessary for a government-backed mortgage. Although projects like Ciudad Kennedy never met the needs of most of the world’s poor, U.S. policymakers promoted the model of self-help housing wherever the Cold War was fought, from Taiwan to Rhodesia, from South Korea to Peru.

9. The Market is the Answer: Section 8

Section 8 housing in Chicago, Illinois

After the collapse of Pruitt-Igoe, Americans looked for alternatives to high-rise public housing. Embracing the free-market rhetoric that came to dominate American politics in the late 20th century, policymakers created a system of public housing that would work through the market. With Section 8 of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, Congress created a housing voucher program, a novel solution to the problem of housing for the poor.

No longer would public housing consist of modernist high-rise towers in parks. Instead, the federal government would provide rental subsidies, enabling low-income families to rent single family homes. In theory, a family could take their voucher to the community of their choice, leaving behind struggling inner cities for the American Dream in the suburbs. In practice, however, families have had limited options. Landlords and municipalities are not required to accept Section 8 vouchers. Nor has the government sufficiently funded the program, leaving the vast majority of eligible renters without housing assistance. In many areas of the country, average rental prices are far higher than the subsidy provided by Section 8.

As a result, there are vast metropolitan regions where there is no meaningful public housing. Yet, thanks to a remarkable lawsuit in Chicago, thousands of poor families have moved to the suburbs. In the case of Hills v. Gautreaux, the Supreme Court ordered the Chicago Housing Authority to stop segregating public housing in concentrated inner-city neighborhoods and instead locate public housing in the suburbs as well. As a result, thousands of low-income families received Section 8 vouchers for suburban housing.

10. Property Rights in Slums: Dar es Salaam

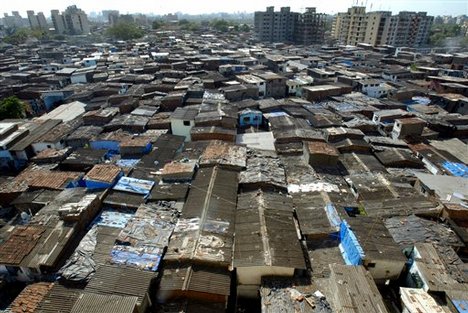

Slums in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

In 2005, Tanzania embarked on an ambitious project to formalize the property rights of hundreds of thousands of squatters who inhabited shacks in the sprawling shantytowns surrounding Dar es Salaam. In Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, seventy percent of the inhabitants live in slums. Most lack access to clean water and sufficient toilets, and there is little infrastructure to deal with sewage. Most are migrants from rural Tanzania, pushed off the countryside yet with few economic opportunities in cities.

Tanzania’s effort to formalize squatter settlements was inspired by the work of Hernando de Soto, the Peruvian economist who argues that the way to reduce global poverty is to expand participation in the market economy—and the best way to do that is to formalize land titles. In slums around the world, the poor held property worth more than $9 trillion, yet their insecure tenure made it impossible for them to capitalize on such wealth. By formalizing their ownership, the poor would have access to credit, facilitating entrepreneurial activity.

In Tanzania, more than 200,000 residents formalized their ownership of slum properties, paying registration fees and property taxes. But the expected expansion of credit never materialized—banks were reluctant to make loans to slum dwellers, regardless of formal titles. The spread of slums in Dar es Salaam is part of a process that is happening around the world. For the first time in history, most people now live in cities rather than in rural areas, and perhaps a billion of these new urban residents live in slums. How to house these people will be a major question of the 21st century.