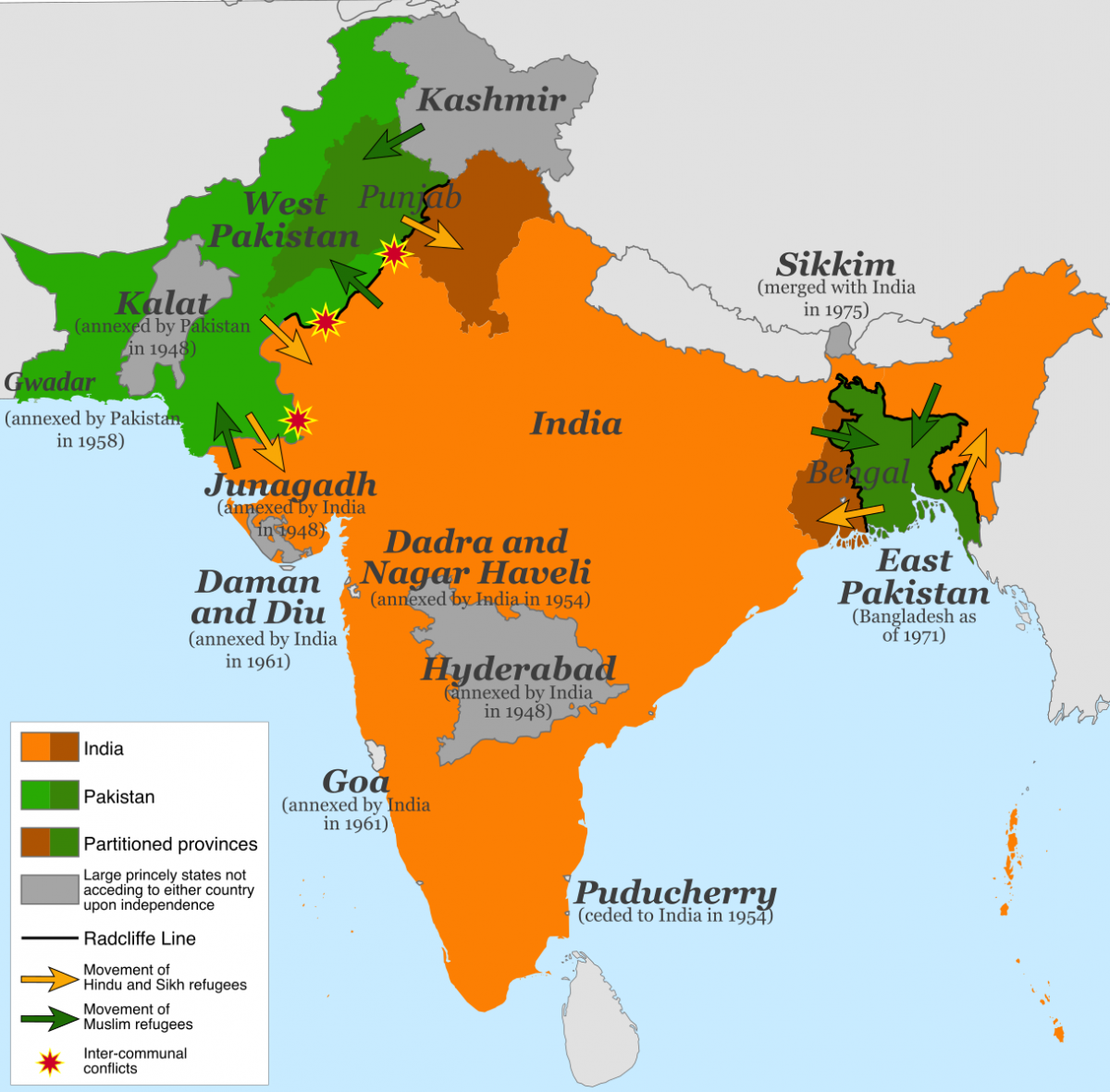

Map of the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of two nations, India and Pakistan. Their independence from the British Empire in 1947 prompted a wave of decolonization that spread across Asia and Africa. Yet alongside the victories of independence came the tragedies of partition, whereby British-ruled India was divided into two separate, independent states.

The violence that accompanied partition, which led to the death of up to a million people and the displacement of millions more, ranks among the worst human tragedies of the twentieth century. Seventy years on, the world is still grappling with the consequences of these seismic events in 1947. From ongoing conflicts at the Indo-Pakistan border, to unresolved questions about the place of religious minorities within both countries, to the traumatic memories of violence that shaped the origins of both nations, the South Asian subcontinent remains marked by that fateful time.

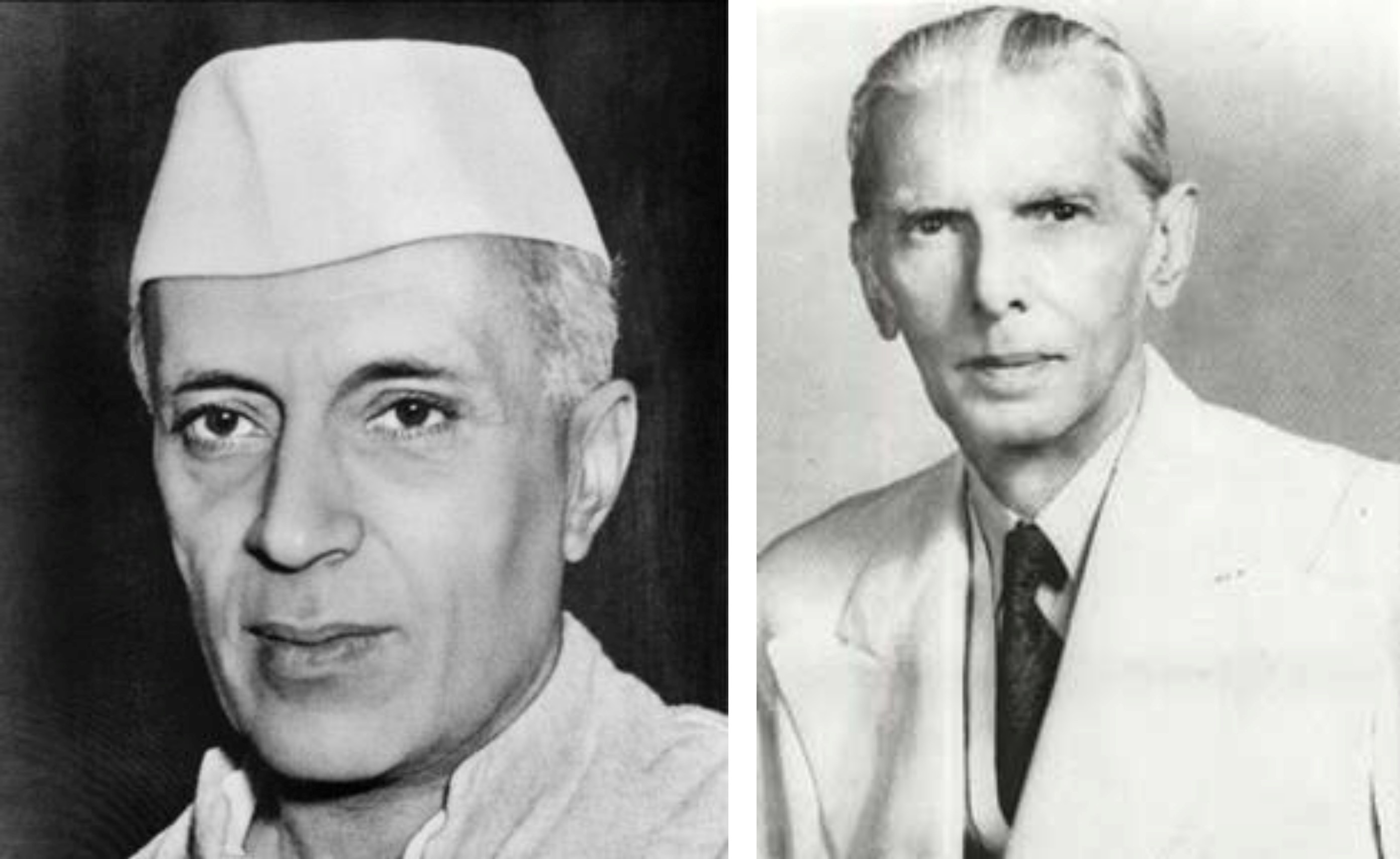

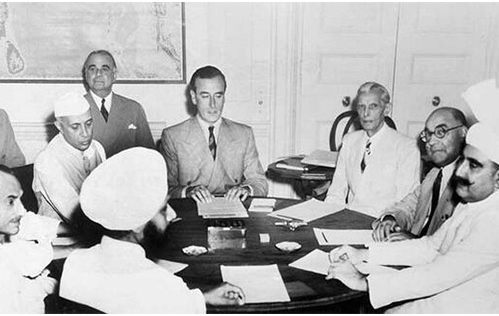

Although independence was the product of decades of anti-colonial struggle, the move towards its final shape—partition—was dizzyingly swift. In February 1947, the British government announced its decision to withdraw from India. Political negotiations between British and Indian leaders followed, with Jawaharlal Nehru representing the Indian National Congress Party and Mohammad Ali Jinnah serving as representative of the Muslim League.

Representative of the Indian National Congress and first Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru (left), and leader of the Muslim League and first Governor General of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right).

Whereas Jinnah called for a national homeland for Muslims, whom he feared would be politically disenfranchised in a Hindu-majority India, Nehru insisted upon a united India that encompassed the entire subcontinent. The British meanwhile, were eager to disentangle themselves from subcontinental politics, and advanced the date of independence to August 1947, a year sooner than Prime Minister Clement Attlee had first promised.

With the clock ticking, in a radio address broadcast on June 3rd across British India, Nehru, Jinnah, Baldev Singh (as representative of the Sikh community), and British Viceroy Lord Louis Mountbatten, announced the plans for independence. These plans accepted that a partition must occur, and that it would divide the provinces of Bengal in the east and Punjab in the northwest. The British civil servant assigned the monumental task of mapping this divide, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, was given just six short weeks to determine India and Pakistan’s new borders.

Radcliffe’s hastily drawn lines on the map created a political border where none had existed before. Areas with a majority Muslim population, in the subcontinent’s northwest and northeast, became designated as Pakistan. Hindu majority areas became India.

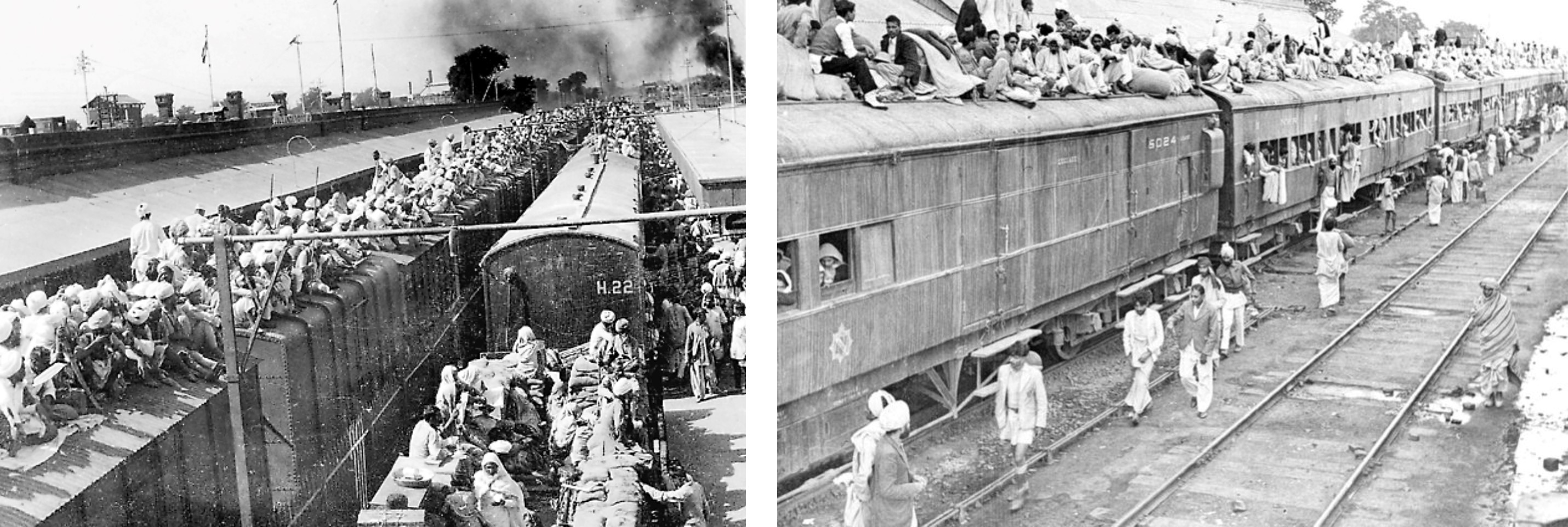

This demographic logic belied an on-the-ground reality, in which Hindus and Muslims—alongside Sikhs, Christians, and others—had lived side by side in all parts of the subcontinent for centuries. Yet, with the stroke of a cartographer’s pen, families and communities found that, virtually overnight, they had become religious “minorities” who now lived on the “wrong” side of the new border. Wary of this minority status, many people left their homes. Hindus and Sikhs fled into India; Muslims crossed in the other direction, into Pakistan. Up to fifteen million refugees made this journey.

Refugees crowded emergency trains leaving to India or Pakistan c. 1947-1953 (left). These trains continued for years after 1947, such as this special train leaving India for Pakistan in 1954 (right).

Historians offer many explanations for why partition occurred. Some seek its underlying causes in the long history of colonialism, which fractured the population along religious lines, while fostering the idea that Hindus and Muslims were distinct political communities. Others cast a critical eye on Indian nationalism, which they argue was unable to overcome these divisions when imagining an independent India.

Still others focus on the last decade of colonial rule, when the exigencies of the Second World War transformed the national political landscape, re-shaped the motivations of provincial politicians, and strengthened the demands for a separate Muslim homeland. They also look towards the final political negotiations of 1947, which took place against a backdrop of growing violence between religious communities that was fueled by propaganda that demonized the “other” community, and by the fevered exhortations of politicians and local leaders.

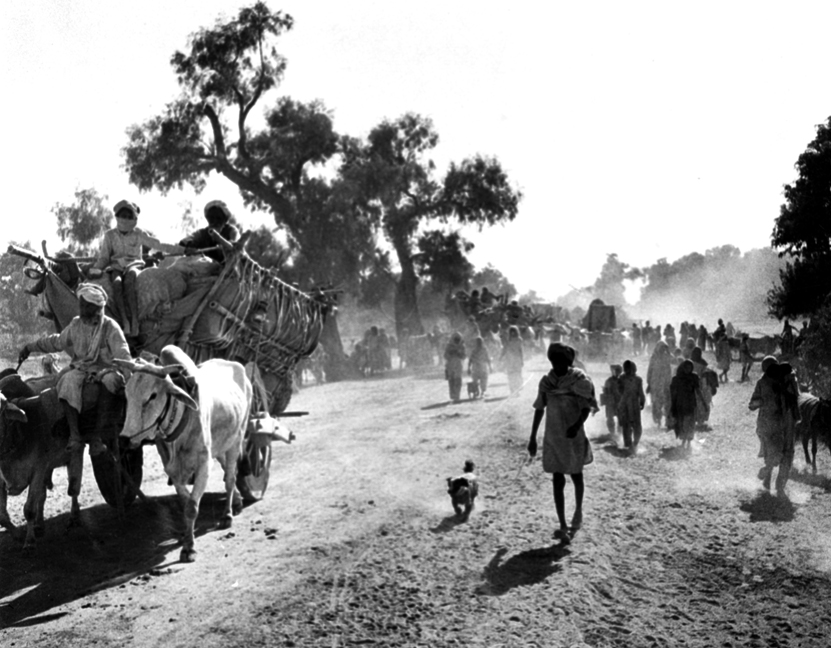

Ordinary people bore the brunt of this violence. They were attacked and killed in their homes and neighborhoods, and while traveling in convoys via train or on foot across the border. Women were raped, assaulted, and abducted in huge numbers as men made women’s bodies the battleground of community identity. The populations of entire villages were executed, and corpses lined the roadsides.

A convoy of evacuees from West Pakistan, 1947.

Police in Delhi searching a vehicle for arms, fearing anti-Partition violence, June 10, 1947.

This unimaginable violence was not simply a spontaneous expression of hatred and brutality, but in many cases was planned and organized. The Punjab in particular was awash with weapons and recently de-mobilized soldiers who had fought in World War II. Some formed paramilitary groups, often funded by local landowners and other elites, who used the chaos of partition to settle old scores, assert claims over land, and secure their own political and economic power.

As these organized paramilitary groups traversed the Punjab in campaigns of ethnic cleansing, there were few who could stop them. The British government was determined not to use its military forces for internal security, and consequently, thousands of British soldiers remained in their barracks as the villages and cities of the subcontinent erupted in bloodshed.

A refugee train, Punjab, 1947.

Many refugees fled for years after partition, such as this convoy at Balloki, Kasur in 1954.

While the terrible violence abated after 1950, the legacies of partition live on today. India and Pakistan have fought three wars and numerous border skirmishes, and each government regards the other with suspicion, if not outright hostility. The border between the two nuclear-armed powers remains contested in Kashmir, now one of the most militarized regions of the world, where civilians are subject to a brutal occupation by the Indian army. Partition’s borders have not held steady in the east either, where in 1971, a bloody civil war led to the creation of the new nation of Bangladesh from the former province of East Pakistan.

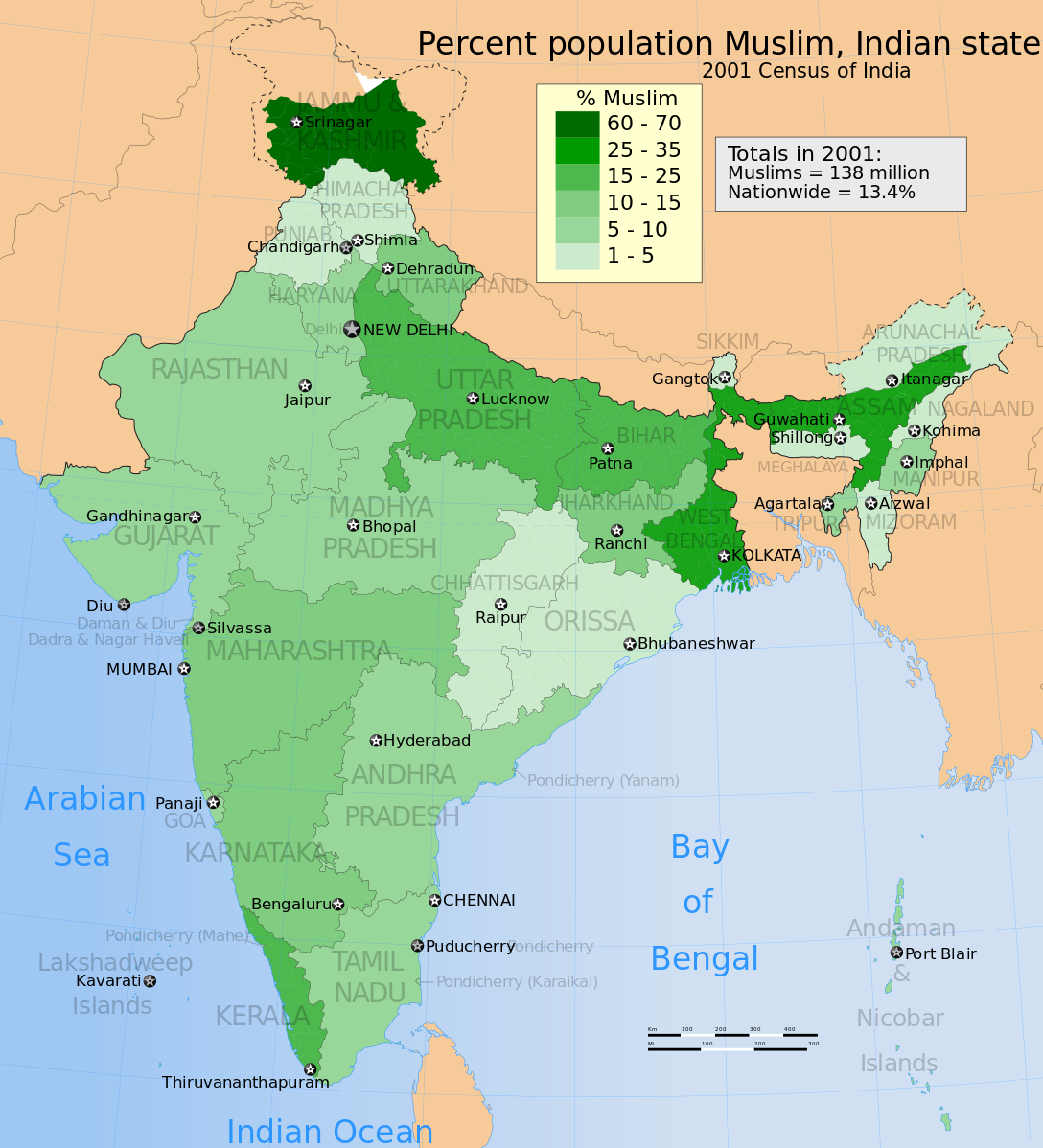

2001 census data on religion, illustrating the percentage of Muslims in India.

Partition also lives on in unresolved questions about the place of religious minorities within India and Pakistan. In India, where there remains a very substantial Muslim minority population, the Constitution makes explicit a commitment to secularism, and to a separation of religion from the institutions of the state. Yet, the notion that Muslims are “outsiders” to India—an idea born out of partition—remains a pernicious presence. It has fueled the rise of a majoritarian Hindu politics that has targeted Muslims for violence in echoes of the horrors of the partition years.

In Pakistan, which was created as a homeland for Muslims, and which has smaller numbers of religious minorities, the relationship between Islam and the state remains fraught, even after successive waves of “Islamizing” policies undertaken by military and civilian governments.

Seventy years on, South Asians still struggle with these legacies. We are now losing the last generation to remember the events of 1947, and there is a new urgency to document the histories of those who experienced partition firsthand. As their stories are collected and shared, perhaps we will be better able to understand the violent turmoil through which India and Pakistan were created, and to imagine more hopeful collective futures.

To learn more about oral history stories from 1947, see the 1947 Partition Archive at: http://www.1947partitionarchive.org/mission