Over two hundred years ago Mary Shelley, at age nineteen, published the gothic novel Frankenstein. It has become a classic of English literature.

She was in a privileged position to craft this rich cultural-historical document because her father William Godwin was a leading enlightenment philosopher, her mother Mary Wollstonecraft was a pioneer English feminist who defended the rights of women, and her husband Percy Shelley was a leading romantic poet. Thus was this precocious and gifted writer poised to dramatize the clash of two cultures—the Enlightenment that celebrated reason and science and the Romantic age that celebrated passion and art.

She was also energized by a series of personal traumas that fueled her feverish story: ten days after her birth her mother died from puerperal fever, at seventeen she eloped with Percy who abandoned his wife, the following year her premature illegitimate child died shortly after being born and her half-sister Fanny Godwin committed suicide, a couple of months later Percy’s wife committed suicide, and just before the publication of the novel Mary gave birth to a daughter, indicating that during a good part of the novel’s composition she was pregnant and in mourning, overloaded with images of birth and death.

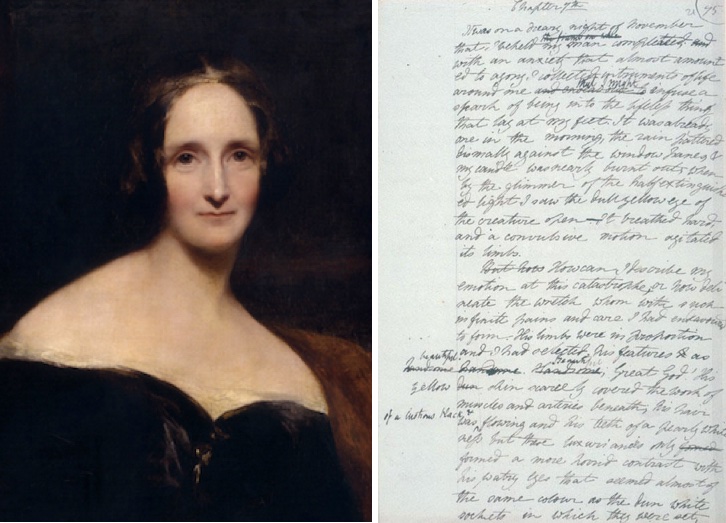

Portrait of Mary Shelley, c. 1840 (left), and a page from a draft manuscript of Frankenstein, 1816 (right).

Mary began the novel one stormy night in the Swiss Alps when her husband Percy and his friend Lord Byron each undertook to write a ghost story. By morning Mary had outlined hers, centering on a quintessential “mad scientist” Dr. Victor Frankenstein who, with the best of intentions of restoring health and prolonging life, undertook to create an eight foot tall human being (subsequently referred to as “daemon” and “fiend”) made of body parts collected from exhumed graves.

The novel’s subtitle, “Or, the Modern Prometheus,” evokes the first great scientist of Greek mythology who in various versions teaches medicine and science, steals fire from Zeus and gives it to humanity, or creates a human being from clay. For those actions Zeus punishes him by having an eagle pluck out his liver every night.

In the novel, Frankenstein creates life and thereby challenges God (instead of Zeus) and is punished by having his creation kill a number of his close relatives and friends, including his bride on their wedding night.

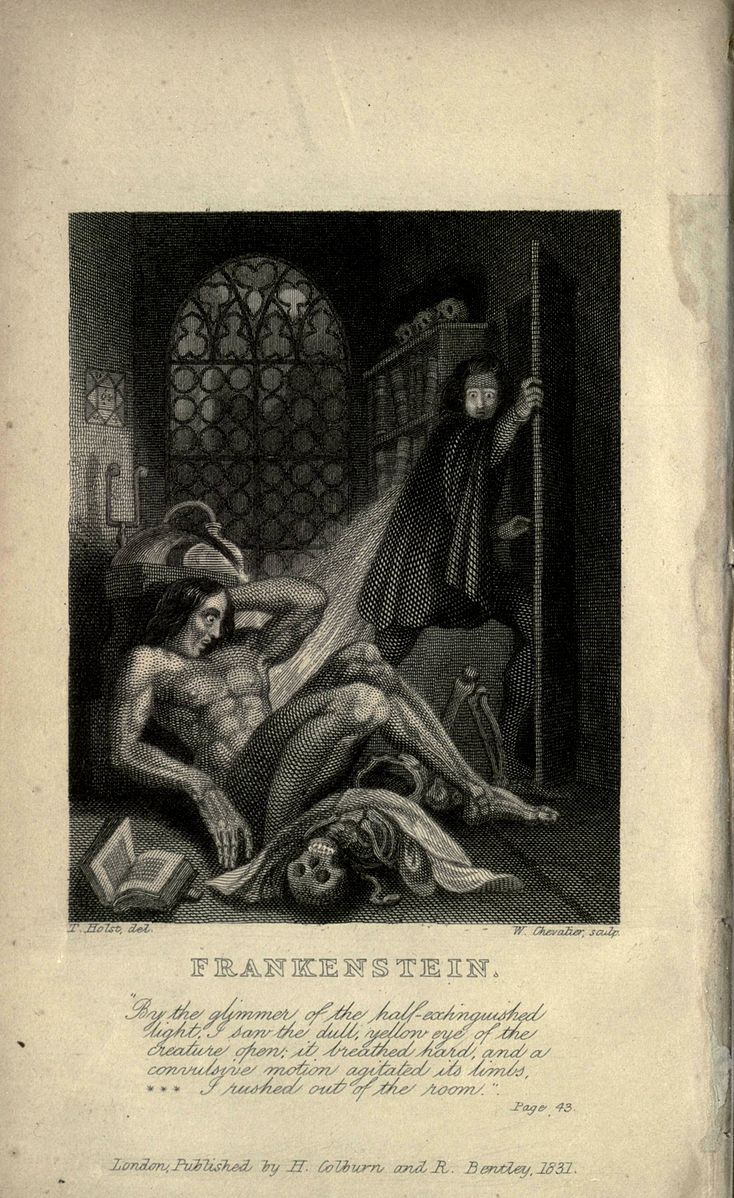

Steel engraving frontispiece to the revised edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, 1831.

Frankenstein instilled life in his creation by some unspecified means, but hints in the novel suggest that it was probably in accord with the laws of electricity and Galvanism as they were known in his time. The creature’s appearance with watery eyes and pale yellow skin was frightening, and Frankenstein fled in horror.

The novel dramatizes the clash between the eighteenth-century enlightenment and nineteenth-century romanticism. Shelley targeted the enlightenment idolatry of reason and mechanistic forces by attacking the idea that man was a predictable and rationally controllable machine. She counters this position with a quotation from Percy’s poem Mutability that rebuts her father’s mechanistic determinism and opposition to free will—“Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; / Naught may endure but mutability.”

The novel also makes veiled reference to the French Revolution with hints that the personality turn of the creature mirrored the turn in the French Revolution from the early hopes for liberty, equality, and fraternity to the subsequent dark days of the Reign of Terror. As Frankenstein reflects, “dreams that had been my food and pleasant rest for so long a space were now a hell to me; and the change was so rapid, the overthrow so complete!”

While the Enlightenment viewed nature as benevolent, the romantics saw it as awe inspiring but potentially threatening. Shelley captures the romantic sensibility of such sublime beauty by setting her story in rugged regions of the Swiss Alps with cascading waterfalls and jagged snow-covered peaks where Frankenstein and his creature coincidentally bump into one another and clash.

The story has been the basis for dozens of films including the 1931 classic that erroneously has Frankenstein give his creation a criminal’s brain. The iconic horrifying face and overall story suggest that the monster is the quintessence of evil, although in the novel the creature’s vengeful turn is caused by the reaction of others to his frightening countenance that was not his fault.

Charles Ogle depicting Frankenstein's monster in J. Searle Dawley's 1910 film adaptation of Frankenstein (left), and Frankenstein's monster, played by Boris Karloff, in James Whale's classic film adaptation from 1931 (right).

The story bears on current moral debates about cloning and the responsibility of a scientist for his discoveries. Frankenstein creates a human being, and as a result he and his family are destroyed by it. But the dark consequences of Frankenstein’s actions do not stem from his brilliant science per se but by the emotional reaction of him and others who all respond negatively to the creature’s frightening appearance.

Still, an underlying message of the novel is that the creation of a human being by unnatural means is a dangerous undertaking fraught with perils from human emotions and sensibilities if not from the displeasure of a god.

A scene from James Whale's 1931 film Frankenstein.

Shelley’s novel is ultimately, however, a celebration of the most ambitious scientific undertakings, even though the two men who first undertake to carry them out fail to do so. Its first narrator, Robert Walton, begins his narration in a series of letters to his sister from aboard a ship that he is captaining on a journey to discover the North Pole. He is full of high-minded intentions in the spirit of the Enlightenment to discover the ultimate origin of the longitudinal lines and of the magnetic force that governs the workings of a compass. While he searches for the ultimate origin of navigational space, he meets Frankenstein who had sought the ultimate origin of life.

Walton never gets to the North Pole, and Frankenstein dies trying to kill his creature. But both of those projects are carried to fruition, in a sense, by the creature who, in the end, is heading to the North Pole (and we have no doubt that he will reach it) where he will kill himself in a suicidal blaze.