After the sledgehammers began breaking down the Berlin Wall on the night of November 9, 1989, after the hammer and sickle flag fell from the Kremlin on December 25, 1991, the world could be excused for breathing a sigh of relief. Fifty years of fear: the specter of nuclear annihilation, the blood and treasure spilled in overt and clandestine warfare, abuses of civil liberties, the arms race treadmill, could, it seemed, be safely put to rest at long last.

The euphoria of peace, however, proved short-lived. In the summer of 1991, as Americans celebrated victory over Iraq in the Persian Gulf War, war broke-out in the former-Yugoslavia. Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic's bloody campaign for a "Greater Serbia" quickly became a test of how well the United States, and the international community could create institutions of governance after the Cold War.

In an attempt to halt the "ethnic cleansing" of Bosnia, the United Nations created the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia in 1993. Following the Yugoslav Tribunal a series of ad hoc war crimes tribunals were created: for Rwanda (1994), Sierra Leone (2002), and Cambodia (2003). While the specific organization and mechanics of each court differed, each sought to reaffirm the legal principles established at the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals after the Second World War. This effort intensified through a series of negotiations that led to the Rome Statute in 1998 and the establishment of a permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) that began operation in 2002.

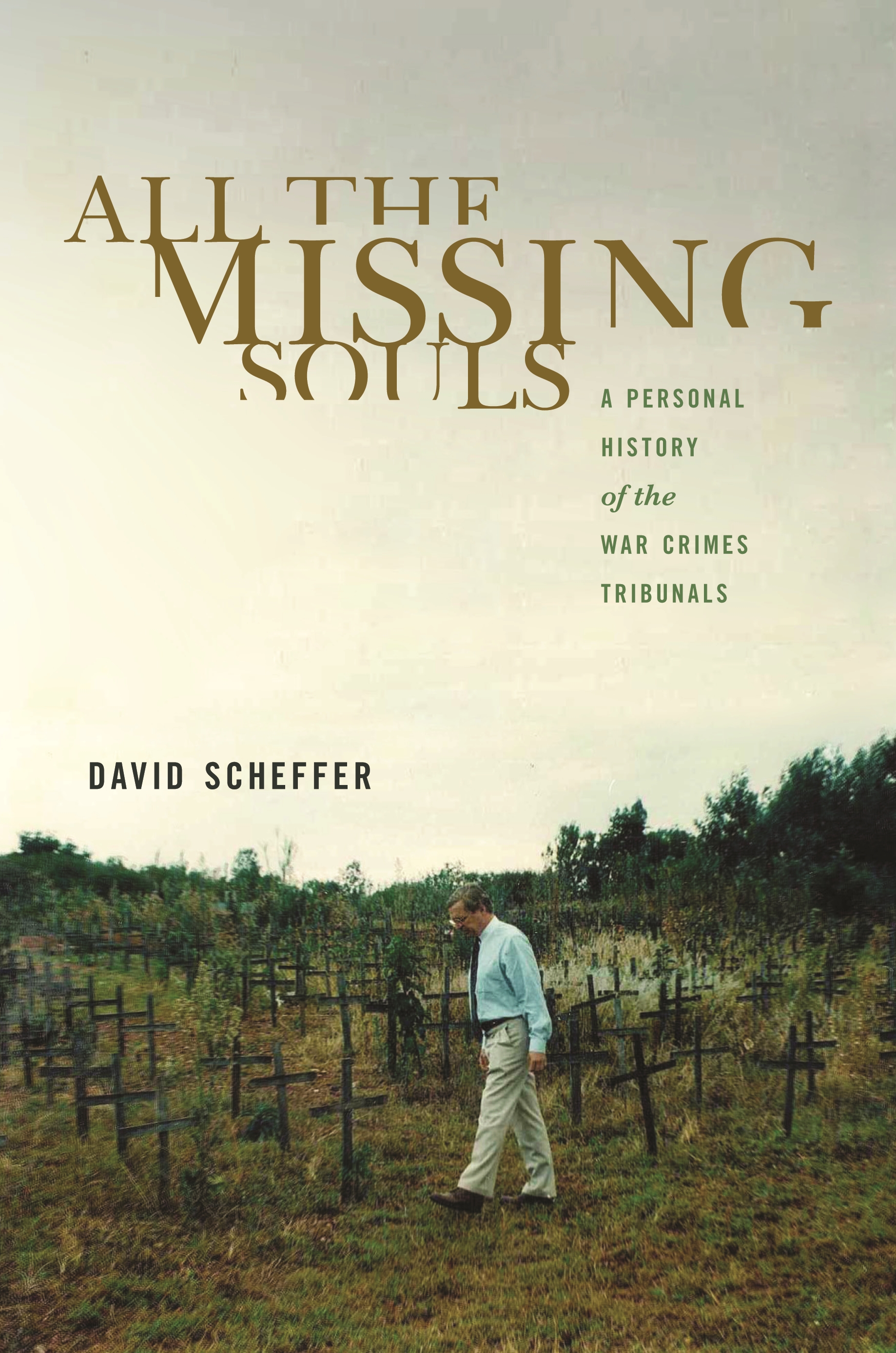

At the center of American efforts in these proceedings was international lawyer David Scheffer, now a Professor of Law at Northwestern University, played a central role in these diplomatic proceedings, first as counsel to Madeline Albright in her post as U.N. Ambassador, and then as U.S. Ambassador at Large for War Crimes Issues (1997-2001). His work All the Missing Souls: A Personal History of the War Crimes Tribunals is his account of this struggle to "enforce a revitalized set of laws against individual war criminals, including political and military leaders who had traditionally enjoyed de facto immunity from prosecution" (5).

Scheffer never forgets the gravity of the crimes that are under investigation and the importance of bringing justice to their victims. In brief vignettes, the "Ambassador to Hell" describes his travels through atrocity zones around the world and his meeting with the victims of acts that Scheffer rightly terms "evil." The reader glimpses the forces unleashed when the rule of law disappears or sovereign power permits unconscionable acts under the guise of legality.

The history of All the Missing Souls, however, is one that largely unfolds in conference rooms and negotiating tables, a world closer to Franz Kafka's The Trial than to Dante's Inferno. Scheffer and his colleagues attempts to push the work of the tribunals and the ICC forward through a multitude of domestic, foreign, and multinational bureaucracies—each organization with its own agendas, and many with higher priorities for their time and resources. In the words of one CIA analyst assigned to search for evidence of atrocities in Bosnia, "Real men don't do this" (38). These meetings, described in detail, will be a valuable reference for future scholars, but they make for a narrative that can be as soporific in the retelling as the discussions must have been for their participants. The reader empathizes with the prosecutor for the Yugoslav Tribunal, Louise Arbour, as she exclaimed in exasperation after innumerable delays stalled the arrest high-profile fugitives, "Everyone has a good reason why someone else should do it. We must break this entitlement to impunity!" (143). Those expecting a Bob Woodward-style Washington "tell all" would be advised to look elsewhere.

Yet the work's emphasis on procedure and the intricacies of bureaucracy can also produce insights of startling clarity. In the case of Rwanda, where 800,000 Tutsi were murdered in the spring of 1994, Scheffer takes issue with the standard narrative that blames the "Black Hawk Down" debacle in Mogadishu for American inaction. Instead, he argues that a "multitude of excuses and devastating delays" (47) in the policymaking process delayed action until it was too late to prevent genocide.

The travails of multilateral diplomacy and bureaucratic infighting also became apparent in the creation of a permanent International Criminal Court. Scheffer details his attempts to walk a fine line between demands for American exceptionalism, that in practical terms meant iron clad protection for U.S. citizens, and the international legal norms of reciprocity and the equality of nations. Senator Jesse Helms declared the court "dead on arrival" (186). The Clinton administration did, with reservations, sign the Rome Statute, on the last possible day, December 30, 2000. The U.S. Senate, however, has not ratified the treaty. Exceptionalism carried the day.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks, the George W. Bush administration embraced a militarized exceptionalism that rejected the laborious process of building international legal norms. In Iraq, at Guantanamo Bay, and elsewhere the United States, with what Scheffer terms acted in "defiance of wide swaths of international law" (417). While the Obama's administration has turned down the rhetorical volume, the principal that the United States can, and should, act without the restraint of international law endures.

So, it is appropriate, in the final analysis, to examine the results of these two legal realities. As Scheffer notes, the tribunals and the ICC have, as of December 31, 2010, tried 151 persons accused of flagrant atrocities, and achieved 131 convictions. All of this was done in open courts, according to international legal norms, with the accused provided with a vigorous defense. Slobodan Milosevic died in a jail cell in The Hague. Meanwhile the Bush administration's hybrid "military commissions," while failing to meet the procedural norms of either military or civilian law, have to-date 4 convictions and 1 acquittal, while creating a class of "enemy combatants" that cannot, it seems be tried or released.

If an argument for the application of the rule of law in international affairs, grounded in efficacy is not enough, Scheffer is more than willing to make his claim in the starkest of moral terms.

"The notion that terrorist suspects should be denied the full range of due process rights that are granted to indicted war criminals perversely elevates them to some higher level of evil, as if that were possible, and only makes sense if the intent is to deprive them of a fair trial. But I would challenge any advocates of such policy to stand before the families of victims of the Rwandan and Srebrenica genocides . . . and to pronounce that the terrorists represent some greater evil requiring a novel regime of law that retreats from due process and humane treatment." (418)

It is well worth pondering how the same legal standards that are taken for granted in our everyday lives can be applied, not only to the most heinous of crimes, but to the world beyond the borders of the United States. In All the Missing Souls, David Schaffer makes the case for the rule of law in the clearest possible terms. We should take heed of his message.