Every November 5, bonfires blaze across Britain as fireworks light the sky and effigies burn.

The celebration commemorates an event from 1605, when authorities discovered Guido “Guy” Fawkes (1570-1606) guarding barrels of gunpowder beneath the House of Lords, prepared to blow up King James I (b. 1566; r, 1603-1625), his family, and all of Parliament.

But Bonfire Night’s endurance stems less from the historical event itself than from the English capacity to reinvent the holiday as political realities change. The conspiracy emerged from decades of religious persecution. England’s break from Rome under Henry VIII (b. 14891; r. 1509-547) plunged the nation into turmoil. By 1603, English Catholics faced severe restrictions: they could not practice openly, attend university, or hold government positions.

When James I ascended to the throne, hope spread among Catholics for religious toleration, in no small part because the new Stuart king (son of catholic Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587)) relaxed fines that had crippled Catholic families for decades.

However, by 1604, James I had intensified persecution, including expelling Catholic Priests, and Parliament reinstated fines. A small group masterminded a desperate response.

Robert Catesby (1572-1605), a charismatic Catholic gentleman, recruited a group of disaffected co-religionists, including Thomas Wintour (1568-1605), John “Jack” Wright (1568-1605), and Guy Fawkes—a seasoned soldier who had fought for Catholic Spain and possessed crucial expertise in explosives.

Their plan was bold: they would rent a cellar beneath the House of Lords, stockpile gunpowder, and detonate it during the State Opening of Parliament, killing King James I, the Lords, and the Commons in one stroke. The conspirators hoped the chaos would allow them to incite a Catholic uprising and install a monarch sympathetic to their faith.

Over several months, they secretly transported 36 barrels of gunpowder into the undercroft. But the plot unraveled when, as the story goes, Lord Monteagle shared an anonymous letter with authorities, who passed it on to the King.

Shortly after midnight on November 5, Fawkes was discovered guarding the explosives with matches and touchwood. Under torture, he abandoned the alias of John Johnson and revealed the names of his co-conspirators. The surviving plotters were captured, tried for high treason, and executed in January 1606—hanged, drawn, and quartered in a gruesome public spectacle.

Parliament quickly established November 5 as a day of Thanksgiving. The Observance of 5th November Act mandated annual commemorations with sermons and bell-ringing. But the holiday served a deeper purpose: it replaced Catholic observances that had structured English life for centuries, including Halloween and All Saints’ Day.

This new holiday filled that autumn void with a celebration infused with English and Protestant meaning—bonfires, communal gathering, and seasonal rhythms stripped of Catholic theology and recast as patriotic Thanksgiving.

Throughout the Stuart era, the celebration reminded Protestant England of the Catholic threat. Anti-Catholic sentiment infused festivities as pope effigies burned and sermons reimagined 1605 as part of a long-term Catholic plot to subjugate England.

This day of Thanksgiving was so popular that it was one of the few holidays that was still celebrated during the Interregnum (which followed the execution of James’s son, Charles I (b. 1600; r. 1625-1649).

The holiday’s political weaponization peaked during the Exclusion Crisis of 1678–1681 when the Catholic community, under 1% of the population and largely apolitical, became a target of hysteria.

This all started when defrocked minister Titus Oates fabricated tales of a “Popish Plot” to assassinate the reinstated Stuart monarch Charles II (b.1630; r. 1660-1685) and replace him with his Catholic brother James (b.1633; r. 1685-1689). Though fictitious, the conspiracy ignited panic and led to the execution of at least 22 innocent Catholics.

For the next several years, November 5 celebrations became tools in parliamentary battles over excluding James, Duke of York, from succession. Whigs staged elaborate processions with effigies of the Pope, Jesuits, and sometimes James himself. In 1679 and 1680, London witnessed massive Pope-burning ceremonies.

These spectacles transformed the day from religious observance into political theater. The crisis gave rise to England’s first real political parties, the Whigs and the Tories, both using the memory of 1605 to advance their agendas.

By the Glorious Revolution, history itself seemed to conspire in the holiday's favor. When William of Orange landed at Torbay on November 5, 1688—eighty-three years after the Powder Treason was discovered—it appeared as divine providence. William’s landing on the anniversary of England’s deliverance confirmed Protestant destiny. Celebrations now honored both deliverances, layering meaning until November 5 became the supreme symbol of Protestant liberty.

For generations, the celebration reinforced Protestant identity and stoked fears of foreign Catholic powers and domestic “Papist” conspiracies.

Each November 5, the English reminded themselves that Catholics threatened their liberties, Parliament, and succession. Bonfire Night and the Gunpower Plot it commemorated became inseparable from English identity: to be English was to be Protestant, and to be Protestant was to remember the Fifth of November.

As religious tensions gradually eased, plays, poems, and pantomimes transformed the man with the matches, Guy Fawkes, from historical figure to popular culture reference. Effigies of Fawkes replaced the Pope, and the rhyme “Remember, remember November 5” became nostalgic rather than cautionary.

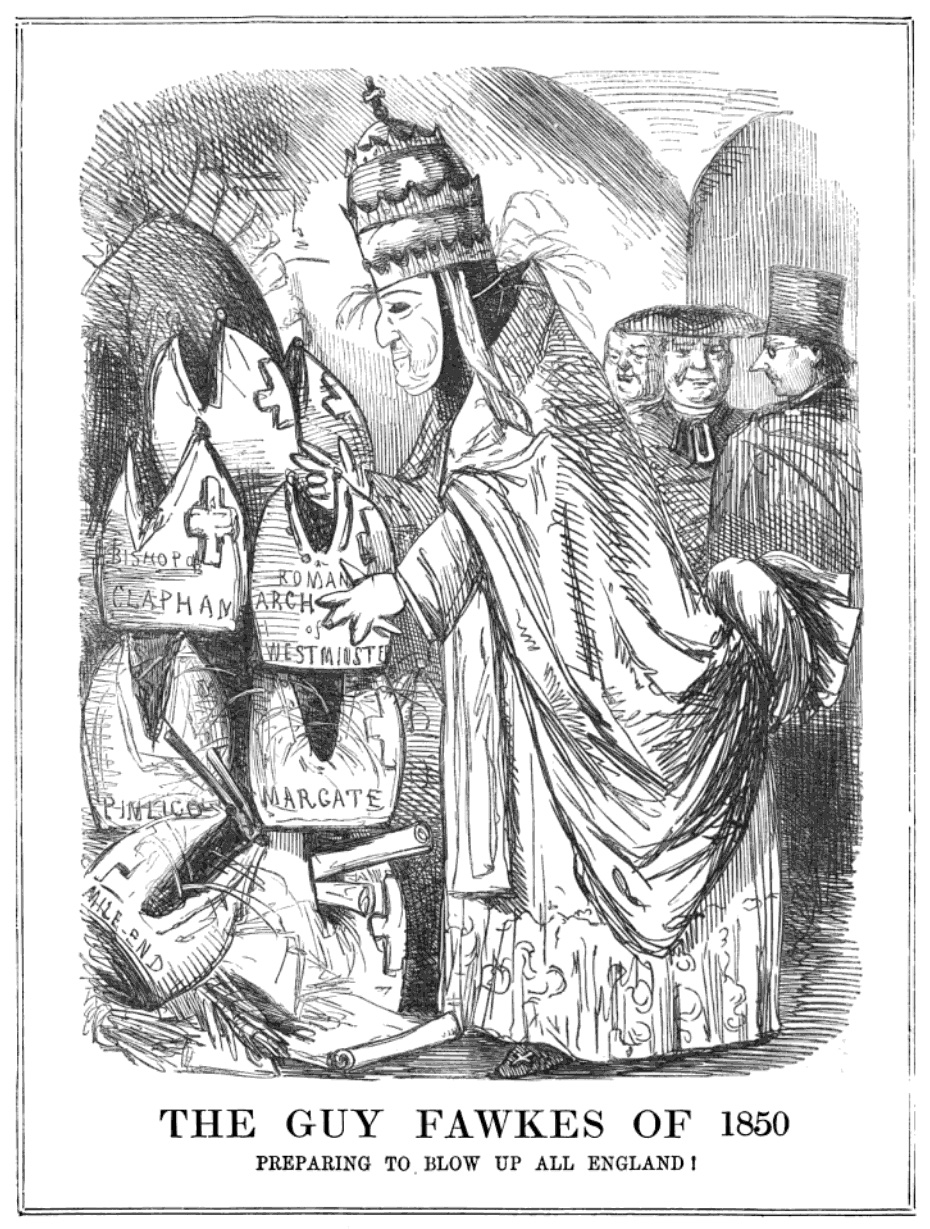

This shift accelerated in the mid-nineteenth century when the Catholic Relief Act of 1829 granted civil rights to Catholics, and in 1850, Pope Pius IX (b. 1792; p. 1846-178) reestablished the Catholic hierarchy in England. Catholics were now neighbors and colleagues. Sectarian hatreds no longer reflected reality.

Even the name changed: “Bonfire Night” or “Gunpowder Treason Day” became “Guy Fawkes Day,” focusing on the individual rather than religious conflict. By the twentieth century, Fawkes became an enduring secular symbol of resistance for some, anarchy for others, and a symbol of autumn celebrations for others.

Today, the English have maintained Bonfire Night’s rituals while stripping away its original meaning. Over time, it has evolved from replacing Catholic holy days to a reflection of the Glorious Revolution and from propaganda to entertainment.

Ultimately, Bonfire Night illustrates that English identity is not a fixed tradition, but a constant process of reinvention shaped by both remembrance and selective forgetting.

![]()

Learn More:

Williamson, Philip and Natalie Mears, “James I and Gunpowder Treason Day.” The Historical Journal, 64 (2): 185–210.

Cressy, David. Bonfires and Bells: National Memory and the Protestant Calendar in Elizabethan and Stuart England. University of California Press, 1989

Cressy, David. “National Memory in Early Modern England,” in John R. Gillis (ed.), Commemorations – The Politics of National Identity, Princeton University Press, 1994.

Fraser, Antonia. Faith and Treason: the Story of the Gunpowder Plot. Doubleday, 1996.

Fraser, Antonia and Brenda Buchanan, David Cannadine, David Cressy, Justin Champion, Mike Jay, and Pauline Croft. Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night. Penguin Books Limited, 2005.

Lynch, Kathleen. “Remember, Remember, the Fifth of November.” Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington D.C. November 7, 2011. https://www.folger.edu/blogs/collation/remember-remember-the-fifth-of-november/

Moriarty, Tom. “The Real Story of Bonfire Night: Why we remember the 5th of November.” English Heritage. N.D. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/real-story-of-bonfire-night/

Sharpe, J. A. Remember, remember: a cultural history of Guy Fawkes Day. Harvard University Press, 2005.

Underdown, David (1987), Revel, Riot, and Rebellion: Popular Politics and Culture in England 1603–1660. Oxford University Press, 1985.