For scholars of the Reformation, the question of legacy is integral. Reformers intentionally built their legacies through autobiographies, carefully crafted sermons, polemics, and—most of all—through the churches they founded.

The prominent reformer, Martin Luther boasts the most complex legacy of his contemporaries because of how he constructed it and how people have used it in subsequent centuries. Historians and theologians often gloss over his anti-Semitism, toxic masculinity, elitism, and vicious anti-papalism substituting a more reverent, spiritual, and academic biography.

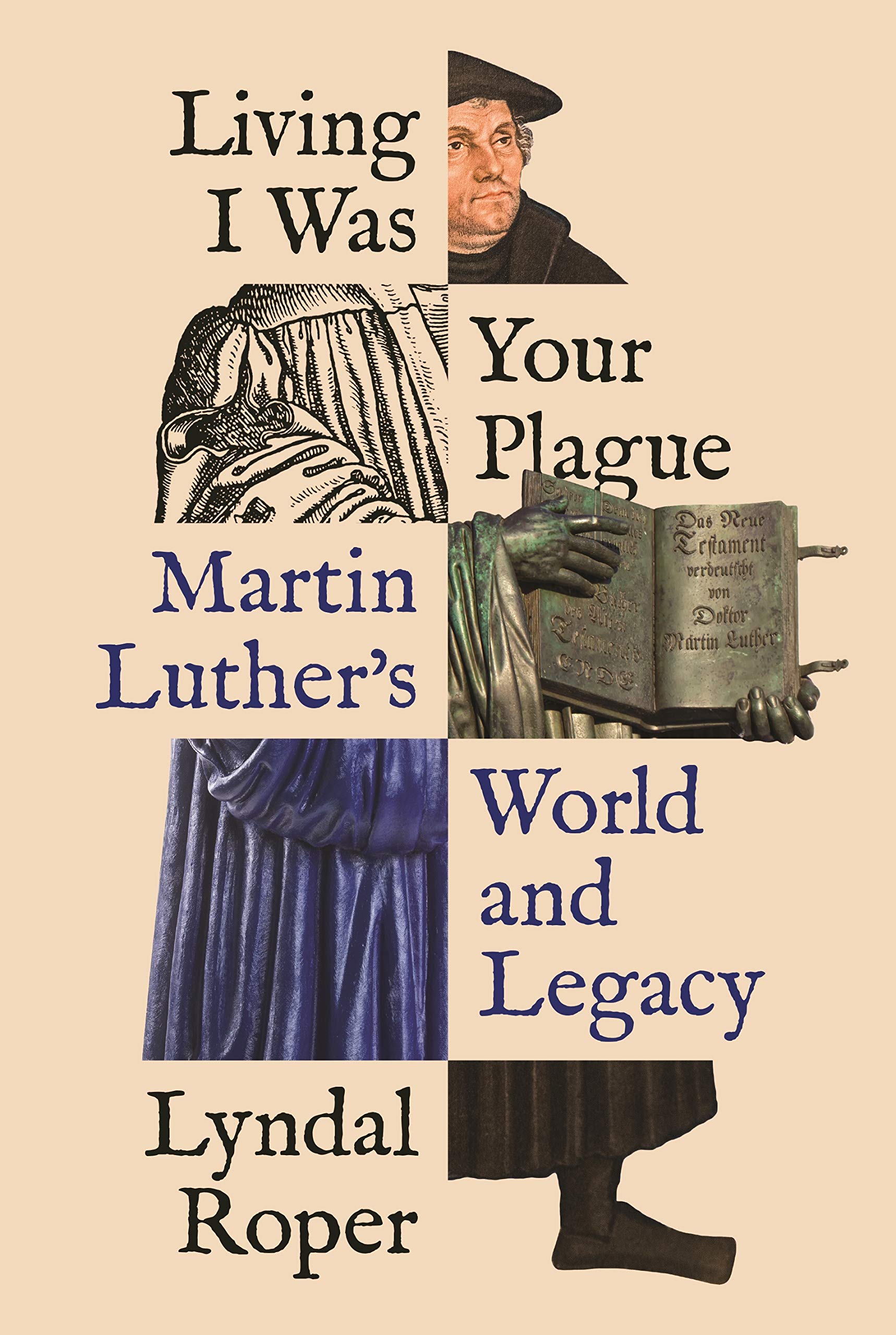

Lyndal Roper’s Living I Was Your Plague: Martin Luther’s World and Legacy grapples with Luther’s complicated legacy through a series of brilliantly illustrated and expertly argued essays. Roper’s book grew out of her observations during the five-hundredth-year anniversary celebrations of Luther’s 95 Theses (Lutherjahr).

Roper, by her own admission, had engaged in what she calls the “memorial cult” with her biography of the reformer entitled Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet (2017), which was published to coincide with the anniversary. Her uneasy feeling elicited a new project that would confront the uncomfortable aspects of Luther’s life while exploring the legacy his life produced.

Roper is not alone in this push to de-mystify Luther’s life and work. She notes Thomas Kaufmann’s explosive book Luther’s Jews: A Journey into Anti-Semitism (2016) that tackled Luther’s blatant anti-Semitism and did not excuse it as a product of his time.

She also draws from Nailing the Myth. 1517: Martin Luther and the Invention of the Reformation (2016) by Peter Marshall, who built upon the argument that Luther’s “theses-posting” (Thesenanschlag in German) never happened, thus creating a false legacy for him and the Reformation. Hence, Roper’s book fits well into a rather recent historiographical trend of cultural histories that tackle difficult subjects and the complex legacies of not only Luther but other reformers too.

The book is divided into seven chapters that are best described as essays. The first chapter entitled “The Luther Cranach Made” is the most central to Roper’s overall argument and the strongest in terms of evidence. This chapter tracks depictions of Luther from the earliest in 1520 to the final image on his deathbed in 1546. While there are thousands of images of Luther, Roper is most concerned with those produced by the workshop of Cranach the Elder. Cranach made Luther the most recognizable face in Europe.

Roper argues that Cranach created the identity of the new religion through his likenesses of Luther. As this new sect defined its belief system and distanced itself from the Church, Cranach’s images changed to match. From the earliest depictions of Luther as a pious monk to the intermediary step of an academic doctor and finally, to a plain, stout man, Cranach wove an evolving religious movement into his art. Luther understood the power of images and used his lifelong friendship with Cranach to create an enduring image of a reformer, a man, and above all a human.

The earliest depiction of Martin Luther by Cranach the Elder, 1520 (left). Cranach's most famous depiction of Luther from 1529 (middle). Luther on his deathbed in 1546 painted by Cranach the Elder (right).

Entitled “Manhood and Pugilism,” the third chapter does not dismiss Luther’s “crudeness, aggressive polemics, and rambunctious masculine posturing” as a product of the times. Rather it confronts it head-on by steeping these crude sides of Luther in a deep understanding of sixteenth-century masculinity. Luther’s masculinity presented itself most ardently in his polemical attacks on both secular and religious authorities. Roper argues that this “tortuous relationship with secular authority” came from a place of “deep-seated dynamics centrally linked to masculinity.”

Among the most overt masculine motifs Luther relied upon was sausage humor in his polemics, the most notable being Against Hans Wurst (1541). This pamphlet nicknames Prince Heinrich of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, who had just lost his dukedom to the Protestant Schmalkdalic League, "Hans Wurst" or Jack Sausage in English. This was one example Roper uses of the frequent “quill fights” Luther found himself embroiled in during the 1530s and 1540s.

The author argues that quill fights mimicked “the swagger of male single combat in an age when noblemen had to prove their honour with their bodies.” Luther drew power from intellectual combat, while the German electors he relied upon had to put up with his polemical attacks on their masculinity because of his cultural and religious authority.

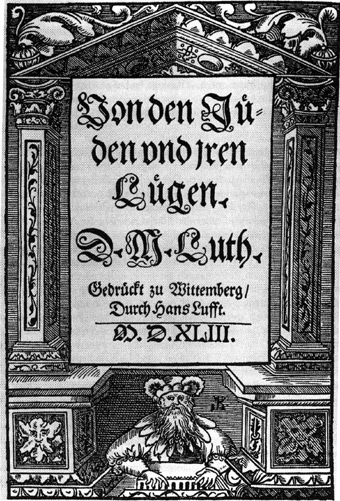

The title page of “On the Jews and Their Lies” by Martin Luther, 1543.

Roper uses Chapter 4 to discuss the importance of names to Luther and his movement. As much as Luther knew the power of iconography, he also knew the power of names. Martin Luther was born Martin Luder in Mansfeld in 1483. He changed his name around 1517 to avoid the poor—and ironic—connotations the noun das Luder (translated to "hussy" or "minx") evokes in German. With this name change, Roper argues, Luther became a self-made man and the head of his own family line, an aspect of masculinity that evolved into a central aspect of Protestant gender roles. Luther’s name became central to his movement and labeled him as the father of his reformation, thus creating an everlasting legacy.

“Luther the Anti-Semite” is Roper’s own attempt to grapple with Luther’s anti-Semitism. Here the book’s argument becomes clear. Luther’s anti-Semitism is uncomfortable, and generations of scholars have swept it under the rug. Recently, scholars have addressed it but Roper, instead, frames it as part of his legacy, a piece that was central to his definition of the Lutheran Church and his salvation.

The author argues through an analysis of several pamphlets authored by Luther that his hatred of the Jewish population stemmed from his theology and involved irrational paranoia, excremental imagery, and revulsion. Above all, it went far beyond that of his contemporaries. Luther believed that his followers were the true “Chosen People” and had displaced Jews in that role. He created a church that’s very identity and legacy were anti-Semitic.

Chapter 7 “Luther Kitsch,” brought the reader out of the sixteenth century and into the modern German commemoration of Luther. While still framing Luther’s legacy in his world, the author emphasizes the Germanness of the 2017 Lutherjahr. She details how the Lutheran Church, German officials, and some historians framed Luther as wholly German to reclaim a German identity void of Nazi connotations.

Roper argues, however, that these celebrations were misguided and did not take Luther the man into consideration as evidenced by the elimination of his anti-Semitism from conversations around this anniversary. Ultimately, she argues that Lutherjahr failed to contextualize his life and legacy.

Despite the excellent scholarship in these five chapters, Roper does fall short in others. Chapters 2 and 5 are the weakest of the group. Chapter 2 seemed to be especially misplaced in the book, with its discussion of Luther’s dreams and Roper’s assertion that they reveal his innermost emotional turmoil and psychology. It feels odd in a work about Luther’s self-crafted legacy when Luther, himself, reviled dreams and warned against reading into their meanings.

Chapter 5 “Living I Was Your Plague” deals with Luther’s dying words and his ferocious anti-papalism. Heavy on theology, it often obscures its argument by digging into minute struggles between Luther and the Papacy.

Still, Roper’s analysis of Luther’s legacy is a welcome addition to scholarship centered on the figure. It tackles important and uncomfortable questions about his life and legacy through beautifully illustrated chapters and a deep understanding of Luther’s worldview. Other regional reformation disciplines would benefit from her cultural approach to the religious upset and then, perhaps, we can move past dismissive arguments that involve the tired phrase “product of their times.”