One hundred years ago this month, the Greco-Turkish war erupted. The war resulted in the largest compulsory population exchange in history up to that time (2 million people) and helped define the concept of ethnic conflict. The war also brought about the Turkish Republic and its severity indelibly shaped modern Greece and Turkey to this day.

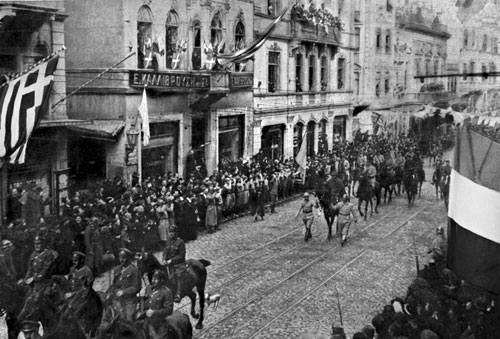

Allied troops occupying Constantinople marching along the Grande Rue de Péra.

The armistice of 11 November in 1918 is credited for ending the fighting of the First World War, but just twelve days prior, the Allied Powers and the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros. The Ottoman Empire was to be partitioned among the Allies, with all powers sending contingents to occupy Constantinople. As part of the deal, Greece received the city of Smyrna.

Smyrna was a wealthy city inhabited mostly by minorities in the Ottoman Empire: Greeks, Jews, and Armenians. For Greece, the city was more than just a prize for participation in World War I. It validated the Greek foreign policy goal of capturing Constantinople and reviving the Byzantine Empire, or “Greater Greece” as they called it.

Greek troops landed in Smyrna on May 15, 1919 and the war began. Local ethnic Greeks and Armenians joined forces with Greek troops. Reports soon circulated that these untrained volunteers committed acts of violence against their Muslim neighbors. Rumors of such brutality enraged an already growing revolutionary faction within the Ottoman Empire led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

A 1919 demonstration in Istanbul protesting the Allies' occupation.

Initially, the Greek Army’s intent was to secure the region surrounding the Smyrna occupation zone, but by the summer of 1920, Greek forces eyed Ankara and began to push deep into the heart of Anatolia. Britain backed this move into Turkish lands because it saw the Greek military as a conduit to crush Kemal’s revolutionary movement. By October of 1920, Greek troops had gained control of northwestern Anatolia. This advance, however, was met with staunch resistance.

Turkish revolutionary forces using guerilla warfare slowed the Greek Army’s progression, and Greek soldiers’ acts of violence against Muslim villagers created fear and panic and fueled ethnic conflict. In acts of reprisal, revolutionary forces brutally murdered Greek Orthodox villagers and forced many others to migrate east to the Greek occupation zone.

A map detailing the zones of control during the war.

The violent acts against civilians committed by both sides did not go unnoticed by the international community and spawned numerous humanitarian relief campaigns.

As the fight dragged on, the Greek public grew weary of the war, and troop morale declined rapidly. Greek desertions soared.

Greek troops with a machine gun during the war.

Britain, anxious about the perceived instability of the Greek government, withdrew its support. Into this vacuum, the Soviets began providing munitions to the revolutionary forces in an effort to check Western expansion and turned the tide of war in favor of Kemal’s forces.

By 1921, the Greek advance had stalled. The Battle of Sakarya in August saw heavy losses for the Greeks and was a strategic victory for the Turkish National Movement. For the Greek forces, this defeat completely halted any hope for advances and sent shockwaves through the government in Athens. After a heated parliamentary debate, the government decided it was far too invested to end the war. Plus, conceding defeat meant that Greece forfeited its territorial claims to Smyrna. This decision would prove disastrous.

Sakarya was the beginning of the end for the Greek campaign. The Greeks were forced to begin a slow retreat toward Smyrna. The final death knell came in August, 1922 with the Turkish Great Offensive—over 100,000 Turks pitted against a disorganized Greek contingent of 200,000.

A Greek depiction of the Battle of Sangarios River (or Battle of Sakarya) in 1921.

Greek soldiers retreating in 1922.

The military operation lasted 24 days and essentially crushed the Greek army, forcing a hasty retreat. The revolutionary forces captured 15,000 prisoners of war and encircled numerous divisions as they tailed the Greek troops to the coast. The Great Offensive concluded when the revolutionary forces entered Smyrna and the city erupted in flames.

Thousands of Greek and Armenian refugees, as well as Ottoman Turks fled in horror, jumping into the sea to escape the fire. The scene was terrifying, as one British sailor described it watching from the deck of the HMS King George: “There were the most awful screams one could imagine… It was a horrible scene; mothers with their babies, the fire raging over their heads… and the people all screaming.”

The view of the Smyrna fire in September 1922 from an Italian ship.

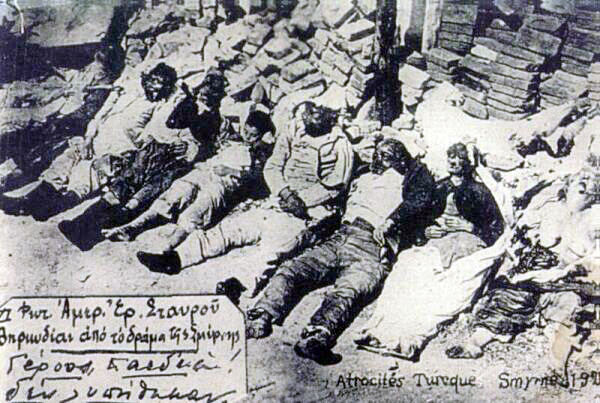

Victims of the Smyrna fire in September 1922.

It took nine days to extinguish the fire, and nearly 100,000 people perished in the flames. The great Ottoman city of Smyrna was reduced to ash. It was the end of the Greco-Turkish War and of a vision of a Greater Greece.

For Kemal and his supporters, the victory was the birth of the Turkish Republic. Kemal abolished the sultanate to become the first leader of the new republic.

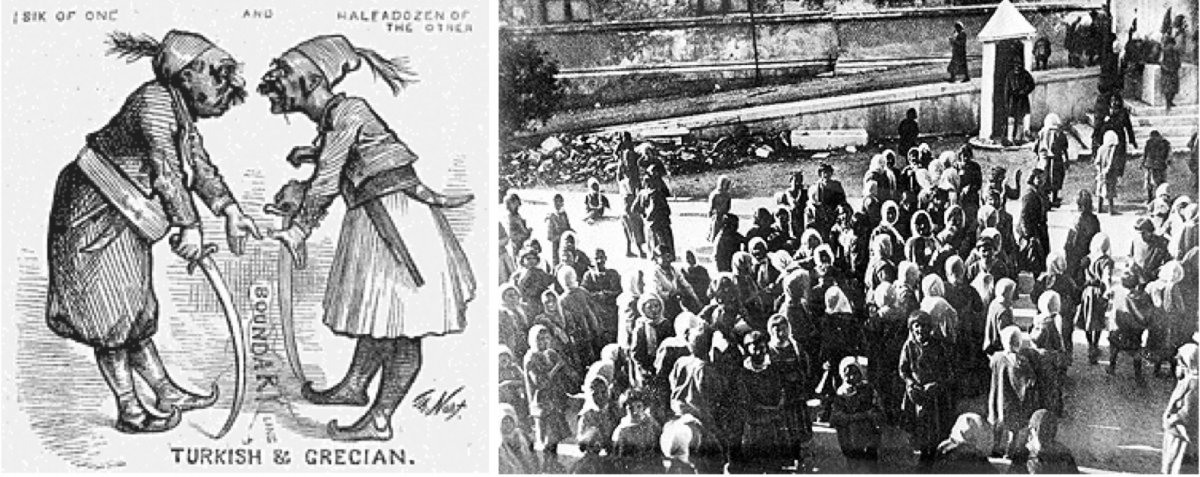

With the war over, the international community started peace negotiations. Britain, France, Italy, and others leading the peace talks decided that a compulsory population exchange was necessary to prevent the deaths of more innocent civilians.

Refugee children from Turkey in Greece in 1923.

With the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, 1.5 million Orthodox Christians and 500,000 Muslims were forced to leave their homes. This population exchange put tremendous financial pressure on an already destabilized Greece, as the country had to care for 1.5 million new refugees. At the same time, it created financial issues for Turkey since many wealthy families were required to leave their homes and cross the Aegean.

The exchange solidified the idea of both Greece and Turkey as homogenous nation-states. Although there were still minority communities left out of the exchange, Greece essentially became an Orthodox Christian nation, whereas Turkey became a Muslim Republic. This war and the concept of religious homogeneity still causes tensions between the two countries today.

A political cartoon depicting the dispute between Greeks and Turks over borders and population exchange (left). Muslim refugees during the population exchange in 1923 (right).

As we approach the centenary of the Greco-Turkish War, we should take the time to reflect on its causes and outcomes and the warnings they give us today. With instability in both the Middle East and Eastern Europe, and the rise of nationalism globally, it may be only a matter of time before another powder keg erupts. In our current climate of religious intolerance, we should mark this anniversary by remembering how innocent people were targeted because of their beliefs.