… like the innkeeper in later Elizabethan Norfolk who scolded customers for letting an argument about the mass and religious images get out of hand: ‘he must be for all companies, and all men’s money.’”

To the lay and scholastics alike, the first thoughts that come to mind when discussing the Reformation is almost never either that of the image of innkeepers mediating theological discussions, or the concept of “religious pluralism.” In Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation, Peter Marshall retells the story of the English Reformation by considering how religion affected the struggle for stability during that tumultuous chapter of English history.

Although Marshall’s monograph, at just shy of six-hundred pages, is not an afternoon read, his “short text,” as he calls it, is surprisingly accessible no matter one’s degrees of knowledge about The Reformation. Divided into four thematic sections, Marshall’s chapters present the English Reformation from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I in plain language and an easy-to-follow narrative.

In Part One, Marshall gives a broad overview of the Medieval Church. Marshall grounds the reader in important ecclesiastical concepts such as “Mass,” “purgatory,” and “the Eucharist.” He then places Medieval theology in the context of late 15th and early 16th century England, and discusses the interaction between the Church, specifically the Pope and the new Tudor dynasty that began in 1485.

Marshall ends the section discussing heresies within the English Church in the early 16th century, concentrating on John Wycliffe’s role in creating the Lollardy by discrediting transubstantiation. The Lollardy led to clerical reform in the 16th century.

In Part Two, Marshall continues to explicate divisions within the English Church that began with the Lollardy. Now more chronological in structure, Part Two addresses the role that Martin Luther’s struggle against Papal authority played in the English Reformation. Within the Monarchy, Marshall follows Henry VIII from his marriage with Anne Boleyn to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The central theme of the instability of the Henry’s Reformation is continually shown throughout Part Two through the rebellions in England and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s.

|

| Hans Holbein's portrait of King Henry VIII (1536) |

Henry’s Reformation and his new role as head of the church generated their own reactions which, while eventually squelched, did not go down quietly. Marshall then goes on to explain how the people, as well as the state, dealt with the role the newly separated Christianity in England in “what, and how, to believe.”

In Part Three titled “New Christainites,” he explores the various faiths of England. Marshall discusses the struggle for stability, both in leadership and doctrine of the Church.

From the death of Henry VI, to the rise and death of “The Boy King” Edward VI, and the succession of Catholic monarch Mary I, Marshall fleshes out traces the tensions between state stability and religious pluralism during these reigns. It is not until Elizabeth I that some form of lasting stability is finally achieved.

The final part of Marshall’s work explores Elizabeth’s consolidation of Protestantism as both the state and common religion of England. Simultaneously, as Roman Catholics again dealt with the subjugation of a Protestant monarch, they also had to reinvent their theology and community.

|

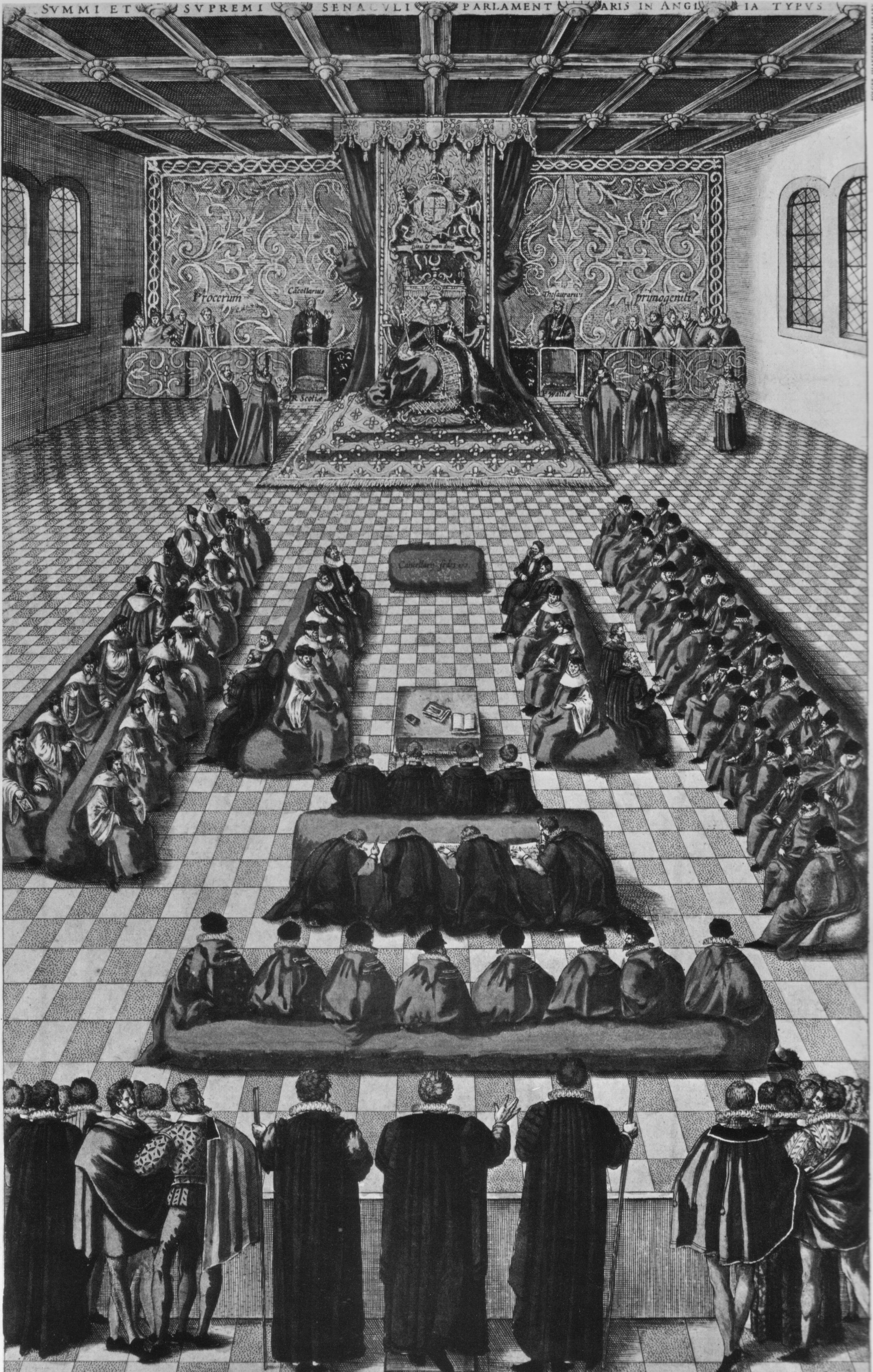

| Queen Elizabeth I in Parliament |

Ending his work in the year 1590, Marshall argues that as no one ever officially stated when The Reformation ended, but that many of the crucial questions and divides of the English Reformation had been settled by that time.

While this is a book that will engage ordinary readers, at the heart of Marshall’s monograph is the argument that the Reformation under Henry VIII required “pluralism and division,” and this “opened a Pandora’s Box of plurality” of religious belief in England in the decades following Henry’s death. Marshall also seeks to redefine, or at least broaden, the understanding of the world and role of religion.

The crowning accomplishment of this text is Marshall’s reconstitution of religion as more than just a set of beliefs and values, expanding the definition of religion to argue that Reformation-era religion is inseparable from community.

Marshall argues that because religion and community were inseparable, in the waning years of Elizabeth I’s reign, the population of England was not only forced to coexist amidst their religious rivalry, but to reckon with what faith-based identity meant for stability and everyday life.

Peter Marshall’s retelling of the English Reformation is an invaluable work of Reformation scholarship. Heretics and Believers is an important update to the general history of the Reformation for the 21st century.

What makes Heretics and Believers stand apart from previous scholarship is the argument of the unifying and communal factor of religion on both sides of the Protestant-Catholic divide. This book will appeal to those seeking an introduction to the Reformation, while the thesis about the Pandora’s Box of religious pluralism will make a lasting impact on scholarship in the decades to come.