When Egypt closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping in May 1967 and built up troops along Israel’s border, Israel responded with preventive strikes against Egypt launching the Six-Day War. It is fair to say that even fifty years later the dust has still not settled from that war.

Writing with eloquence and providing much detail, Guy Laron, a scholar of international relations at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, offers a broad contextualization of the origins of this war. Drawing on a variety of Israeli, American, British, German, Russian, and East-European archives, The Six-Day War: The Breaking of the Middle East demonstrates that in addition to the conflict over the Straits, the war also resulted from economic turmoil, military domination of civilian governments, and insufficient pressures by the U.S. and Soviet superpowers to deter regional military violence.

Laron discusses how the economic turmoil in Syria and Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s created the conditions for military coups and for administrations that deemed the application of force a welcome distraction from domestic problems. At the same time, Laron emphasizes that Egypt’s regime under Abdul Gamar Nasser, Syria’s Baath Party, and Jordan’s King Hussein rarely spoke with one voice. In fact, Syria had previously grown tired of Egypt’s claims to speak on its behalf. Jordan (and Saudi Arabia), meanwhile, had given significant military aid to the royalists in North Yemen’s Civil War (1962-1970) at the same time that Egypt’s overextended commitment of troops to North-Yemen’s republicans had produced what came to be known as “Egypt’s Vietnam.”

|

| Israeli Prime Minister, Levi Eshkol, who was pushed from all sides to implement a preventative strike against Arab neighbors. |

What finally united the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian regimes in an uneasy coalition against Israel in 1967 was the general realization of Israel’s military superiority and a reliance on bad Soviet intelligence about an alleged Israeli troop build-up near Syria. Such intelligence, Laron shows, had resulted from deliberate Israeli attempts to deceive, but also from the Syrian fabrication of evidence intended to draw Egypt and potentially even the Soviet Union into the conflict.

The fact that Nasser’s hawkish Egyptian military leaders kept him out of the loop, moreover, not only facilitated the escalation of conflict but also laid the foundation for Israel’s devastation of Egypt’s air force. His inability to control the military and the resulting decisive Egyptian defeat discredited Nasser, the erstwhile hero of the 1956 Suez Crisis and most famous advocate of Arab nationalism.

On the Israeli side, military leaders of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) proved similarly influential over civilian authorities who still hoped to use diplomacy to reopen the Straits of Tiran. Chief of the General Staff Yitzhak Rabin and Major General Ariel Sharon—both of whom would garner glory in the conflict and become Prime Minister—proved particularly adroit in pushing Israel toward war.

Prime Minister Levi Eshkol’s position was weakened by well-publicized attacks by Israel’s founder Ben Gurion and the broader Israeli perception that he was unprepared for any Arab attack. Such pressures, then, coupled with Israeli frustrations that its neighbors encouraged and selectively supported the newly-founded Palestinian Liberation Organization, helped sway Prime Minister Eshkol to move from a defensive to an offensive mindset—“Rabin’s Schlieffenplan,” (145) as Laron coins it in pointed allusion.

|

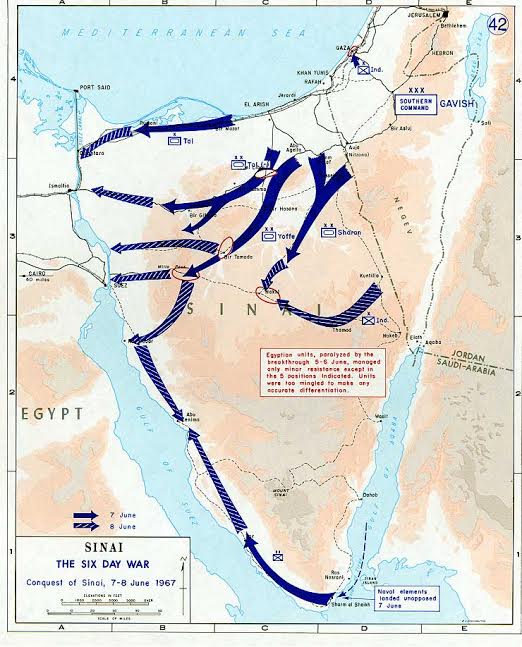

| Rabin's "Schlieffenplan:" an early Israeli western offensive against Egypt followed by an eastern strike against Syria and Jordan. |

Crucially, however, Israel would not have acted without American permission. Laron’s analysis of what some have called the "red-light, yellow-light, green-light" debate is remarkable. Providing a trove of evidence, Laron leaves little doubt that President Lyndon B. Johnson and National Security Advisor Walt Rostow surreptitiously gave Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban the green light to act unilaterally against its neighbors. The White House did this with the backing of the CIA and the Pentagon but against the will of the State Department which presciently foresaw the long-term complications that could arise for the United States in the Middle East. Just as importantly, this support behind the scenes likely helped to convince Israel to hold on to the newly-gained territories. Israel had originally intended to return those territories--, including the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Height-- in exchange for security arrangements after the war.

Finally, the Soviet Union assumed a determinedly ambiguous role in the conflict. Torn between Soviet hawks and doves, the Brezhnev administration, never one to replicate Khrushchev's enthusiasm for Third-World commitments, sent mixed signals to Egypt and Syria. The Soviets expressed their support and provided arms and tactical doctrine to Egypt and Syria. But, they also acted cautiously to avoid an all-out escalation of a conflict that could have resulted in war with the United States.

Clearly, the Six-Day War’s multiple domestic and international dimensions make for complicated analysis, and Guy Laron succeeds in tracing the manifold developments of this convoluted conflict. His arguments are convincing and substantiated through his impressive incorporation of archival materials.

Yet, Laron’s greatest weakness lies in the book’s story-telling, which often make it exceedingly difficult to see the forest for the trees. Overwhelming the reader with detail and sporadically neglecting to connect the various chapters and themes, Laron can make events difficult to follow.

A lack of narrative cohesion notwithstanding, this work stands out through Laron’s brilliant insights and eloquent writing. Undoubtedly, a perusal of The Six-Day War will prove useful to scholars of international relations and the Middle East across a variety of disciplines but also offer rewarding reading experiences to public audiences with much patience and stamina.