Nearly 30 years have passed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In that time, the former Soviet Republics have followed different political trajectories. The Baltic States have joined the European Union while Ukraine has become an international hotspot since the 2014 Russian invasion. Armenia, too, has undergone political turmoil, including revolution in 2018. As historian Pietro Shakarian argues this month, this recent, peaceful transition of power was rooted in Armenia’s political past but its success might well prove a model for other countries in the region.

In April and May 2018, the small nation of Armenia experienced a revolution. On August 17, one hundred days after the upheaval’s end, thousands of Armenians—young and old, workers and professionals—gathered in the capital city Yerevan for a political demonstration.

Waving the tri-color Armenian flag and filled with hope for a better future, the crowd roared with enthusiasm when the revolution’s leader, and now Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, began to speak. The whole event felt more like a carnival than a political gathering. Parents held young children on their shoulders, as others held signs bearing anti-corruption slogans and images of former authorities with their faces crossed out.

Demonstration at Republic Square, Yerevan, August 17, 2018 [photo by author].

Although the revolution focused on a single demand (the resignation of President-turned-Prime-Minister Serzh Sargsyan), social concerns played a major role in the mobilization of the population. Indeed, some commentators noted that it had more in common with “democratic movements in Latin America [in the 1970s and 1980s] rather than … other revolutions in the post-Soviet world.”

Unlike the so-called “color revolutions” that took place in Georgia and Ukraine in the early 2000s that were overtly anti-Russian, the Armenian revolution did not become entangled in the deteriorating relationship between the United States and the Russian Federation.

Demonstrators in Tbilisi, Georgia during the Rose Revolution in 2003 (left). The first day of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004 (right).

The Armenian revolutionaries took a wider, more inclusive approach and steered clear of a messy and prolonged confrontation with Russia. Eschewing nationalism and NATO, the April Armenian Revolution avoided the pitfalls and violence of Ukraine and Georgia.

To be sure, these were choices realistic for a small country locked in a complicated and hazardous part of the world: Armenia is dependent on Russia for regional security and economic opportunity. But these were not the only considerations for the Armenian revolutionaries in their pragmatic approach toward relations with Moscow. In fact, most Armenians have positive attitudes toward Russian people and culture and the Armenian revolutionaries saw their political reforms as a paradigm that could inspire civil society in Russia also.

Photograph of the Armenian Revolution, Yerevan, April 22, 2018.

In this way, the 2018 events in Armenia represent a new kind of revolution in the world of the former Soviet Union. By not directing their movement against Russia or any other country, the Armenian revolutionaries made their revolution more relevant globally to civic struggles for social change.

The themes of the revolution (opposition to corrupt government and inequality, for example) are universal issues that are increasingly relevant across the globe today. They may also serve as a model to embolden social movements and grassroots democratic activists across the former Soviet Union and in Turkey and Iran as well.

What is Armenia?

Tucked in the region of the Caucasus Mountains, Armenia is situated on the southwestern extremity of the former Soviet Union. Located in the shadow of the Biblical Mount Ararat, Armenia was the first country to officially adopt Christianity in the year 301 CE (or 314 CE, depending on whom you ask). Its people developed their own distinctive alphabet during a continuous history that dates back centuries. Armenia’s neighbors include Christian Georgia and Shia Muslim Azerbaijan.

Hemmed in by the Black and Caspian seas, this mountainous isthmus stands at a juncture between east and west, along the trade routes of the old Silk Road, where the interests of Russia, Turkey, and Iran converge.

That strategic location made Armenia vulnerable to invading imperial powers. Armies of Assyrians, Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, Seljuks, and Mongols all marched through Armenia.

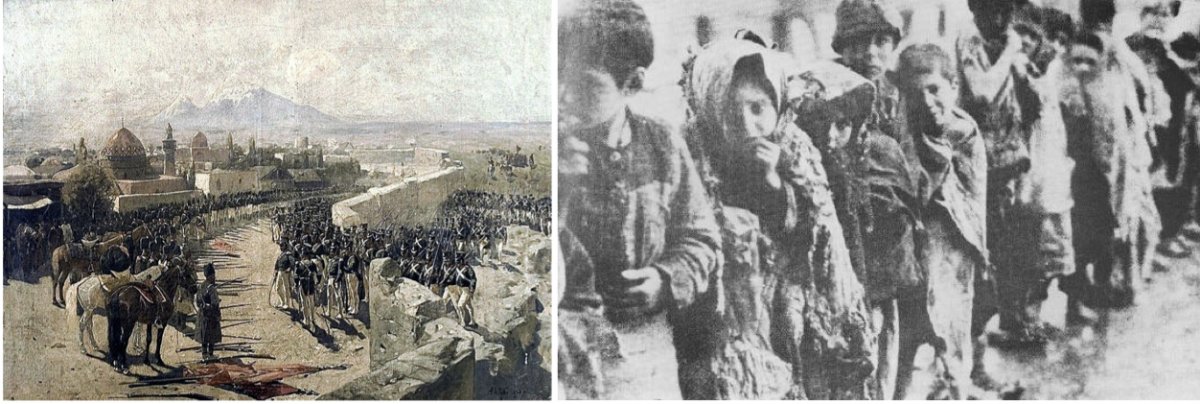

By the 19th century, the area had become a vast battleground between Imperial Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and the historical Armenian homeland was divided between the two. When World War I broke out, Ottoman Turkish authorities launched a full-scale genocide of its Armenian population. Armenians had been subjected to massacres previously, but nothing on the scale of the genocide of 1915. By the time it was over, 1.5 million Armenians had been killed.

Russian troops capturing Erivan fortress in 1827 during the Russo-Persian War (left). Orphan children from the Armenian Genocide, 1915 (right).

Meanwhile, as Imperial Russia plunged into revolution and civil war, Russian Armenia declared independence in 1918 and staked out a tenuous existence, beset by territorial conflicts, political crises, and a massive influx of Ottoman Armenian refugees fleeing the genocide. The USSR quickly absorbed this nascent state and officially declared it a Soviet Socialist Republic in 1920.

Revolutionary Roots

Even as a Soviet Socialist Republic, Armenians developed a tradition of political protest. One year after Stalin’s death, in March 1954, Soviet Armenian statesman Anastas Mikoyan, an ally of Nikita Khrushchev, delivered a speech signaling the beginning of the Thaw in Soviet Armenia and set the stage for increased national and political expression in the republic.

In 1965, on the 50th anniversary of the 1915 genocide, at least 100,000 people converged on Opera Square demanding that the Soviet government officially recognize the tragedy. In response, Moscow sanctioned the construction of the Armenian Genocide memorial at Tsitsernakaberd Hill in Yerevan.

Two decades later, in response to Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost and perestroika, Armenians took to the streets in large numbers.

Location of Nagorno-Karabakh highlighted within the post-Soviet Caucasus [map by author based on 1995 CIA ethnolinguistic map of the Caucasus].

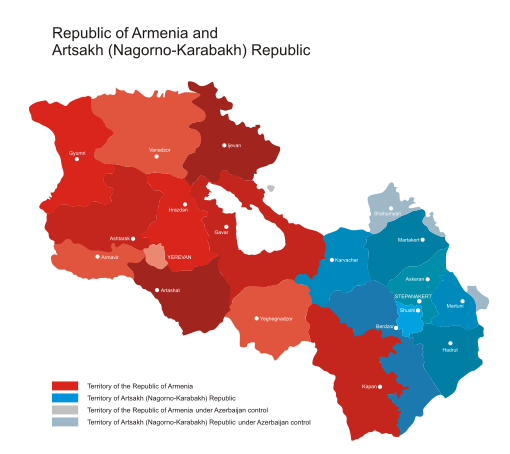

In 1988, the majority-Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, an autonomous region that had been absorbed by Azerbaijan during the Russian Civil War, began to demand the transfer of the region to Soviet Armenia. Mass protests among the Karabakh Armenians soon spread to the Soviet Armenian Republic. Anti-Armenian pogroms erupted in the Azerbaijani city of Sumgait. Moscow’s responses were often confused and contradictory, contributing to distrust between the warring parties.

The movement that arose among protests over Nagorno-Karabakh became known as the “Karabakh Movement,” and the vast majority of Armenians rallied around it. By February 1988, as many as a million people (one third of the population) poured into the streets of Yerevan demanding unification with Karabakh. An earthquake in northern Armenia in December 1988 only added more frustration that fed into the movement.

Karabakh Movement demonstration in Yerevan, 1988 [photo by Ruben Mangasaryan].

Western commentators often present this campaign as a strictly nationalist one, glossing over its ideological diversity. Although Karabakh was a central issue, the struggle was not defined by it. The protesters were concerned with other issues too, such as the environment and the legacy of Stalinism.

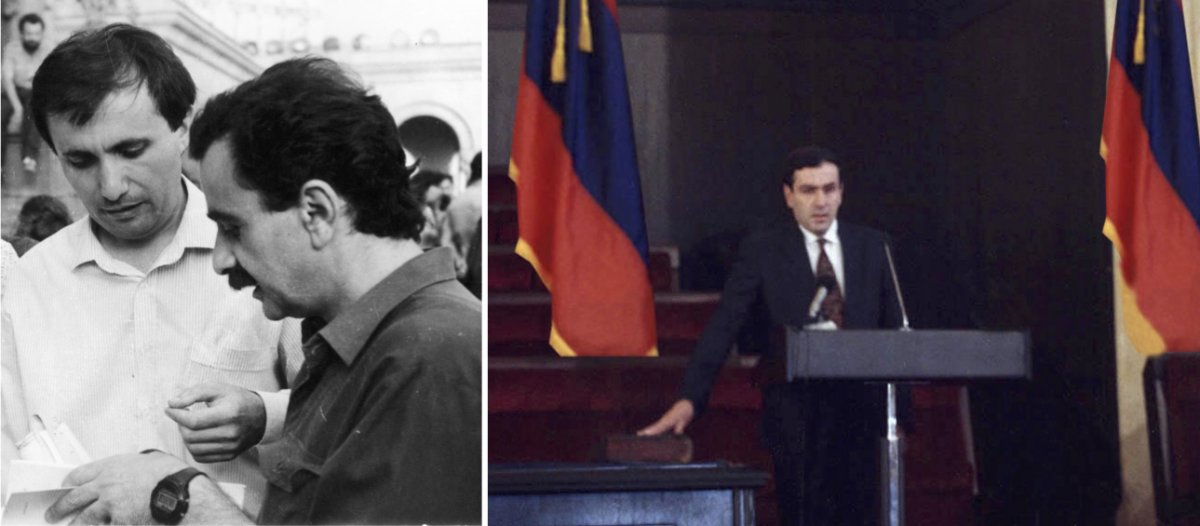

The movement’s leadership—the Karabakh Committee—was ideologically diverse. Activist Ashot Manucharyan espoused a democratic socialist vision, while Levon Ter-Petrosyan, a scholar of Syriac manuscripts and later Armenia’s first post-Soviet president, preferred a more liberal path.

Karabakh Committee member Ashot Manucharyan on the left with Ashot Dabaghyan on the right (left) [image courtesy of Bagrat Dabaghyan]. The inauguration of Armenia's first president, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, in 1991 (right).

The Karabakh Committee also worked to drown out the voices of chauvinistic Armenian nationalism and to emphasize that the movement was not aimed against Azerbaijanis, Russians, or other ethnic groups.

Significantly, the question of secession from the USSR was not on the agenda of the Karabakh Movement until the eve of Soviet dissolution in 1991. Moscow’s inability to resolve the Karabakh quandary fueled popular frustration that translated into support for secession from the USSR.

Celebrations after the September 21, 1991 referendum declaring Armenia’s independence.

However, even as such sentiments grew, the Karabakh Committee’s position on secession was far from unanimous. Not only were there those who sought to maintain the benefits of cooperation between republics, but many also feared the implications for Armenia’s security. Seceding from the Soviet Union could expose Armenia to attack from Turkey.

Nevertheless, Armenians voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence in September 1991. The move was not officially recognized by Moscow until the dissolution of the Soviet state with the signing of the Belavezha Accords in December.

The December 1991 signing of the agreement to eliminate the USSR and establish independent states.

The creation of an independent Armenia, therefore, happened as much because of events in Moscow as through actions in Yerevan. In the words of Ter-Petrosyan, “We didn’t leave the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union left us.”

Independence and Its Discontents

Armenia’s early post-Soviet years were intensely unstable. Independence might mean freedom but it also entailed a loss of the economic connections Armenia had enjoyed to other now-former Soviet republics. Losing these trade networks meant the drying up of markets for key industries and a painful flight of jobs.

This problem was exacerbated by the post-Soviet Armenian government’s economic “shock therapy,” conducted, as in Russia, through the radical privatization of economic assets. Neoliberal privatization combined with the pre-existing culture of Caucasian clan politics and the legacy of the black market economy to create conditions for corruption and the rise of oligarchs.

Armenian soldiers in Karabakh in 1994 using Russian AK-74 assault rifles.

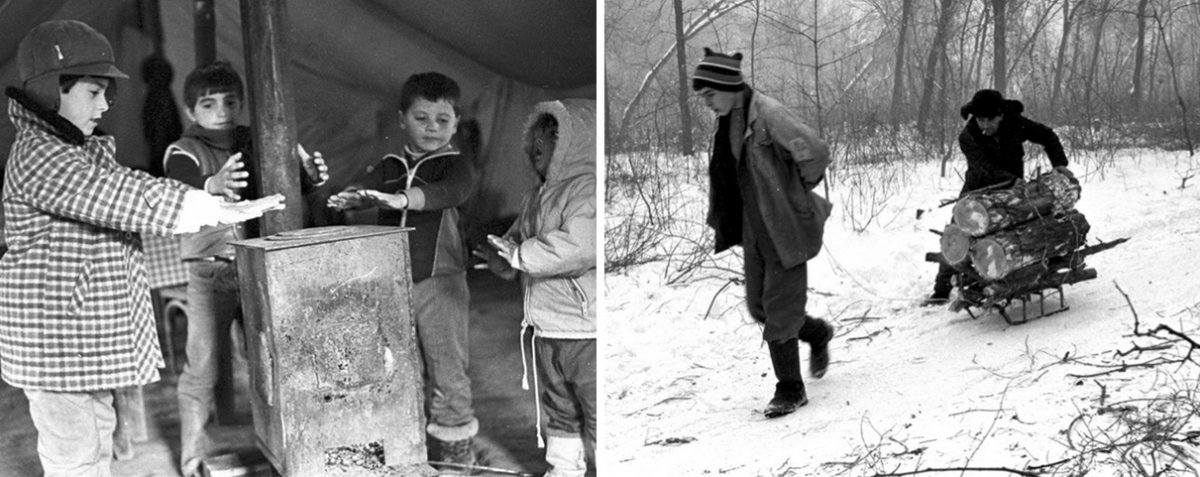

Additionally, the independence of both Armenia and Azerbaijan elevated the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute from an ethnic conflict within a single state to a full-scale war between two newly independent countries. The war caused tens of thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. It also resulted in an economic and energy blockade by Azerbaijan and Turkey. The winters of the years of 1991-94 are still remembered by most Armenians as exceptionally cold and harsh.

A Russian-brokered ceasefire ended the Karabakh War in 1994, winning independence for the Karabakh Armenians. But the end of the war brought new issues to the surface. Beginning in 1996, successive presidential elections were marred by vote-rigging and vote-buying, creating a lack of public trust in the country’s political institutions.

Armenian children struggling to keep warm (left) and a boy and his father bringing home firewood during the energy crisis of the 1990s (right).

In 1998, President Ter-Petrosyan was forced to resign by the country’s political forces over his controversial support for a proposed compromise settlement to the Karabakh conflict with Azerbaijan. He was succeeded by his prime minister, Robert Kocharyan, a native of Karabakh, veteran of the Karabakh War, and the first president of the independent self-proclaimed Karabakh Republic.

Kocharyan consolidated his power behind a political party known as the Republican Party of Armenia (RPA). Under Kocharyan, the RPA dominated Armenian politics for the next two decades. A construction boom in Yerevan allowed the economy to grow and the country to stabilize. However, the growth was largely concentrated in the capital, while the provinces continued to languish in post-Soviet shock.

A map of the Republic of Armenia and Artsakh Republic.

Unemployment, poverty, emigration, and corruption remained endemic. By the time “color-revolution” fever swept the post-Soviet region in the early 2000s, Armenians were exhausted by years of war, mass demonstrations, state collapse, energy shortages, economic instability, and political crises. Although the revolutionary impulse was muted, it was certainly not extinguished.

A New Period of Protest

The presidential election of 2008 signaled a turning point for Armenia. The fierce campaign between Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan and Ter-Petrosyan returned now to the political stage. In the end, Sargsyan won a controversial victory.

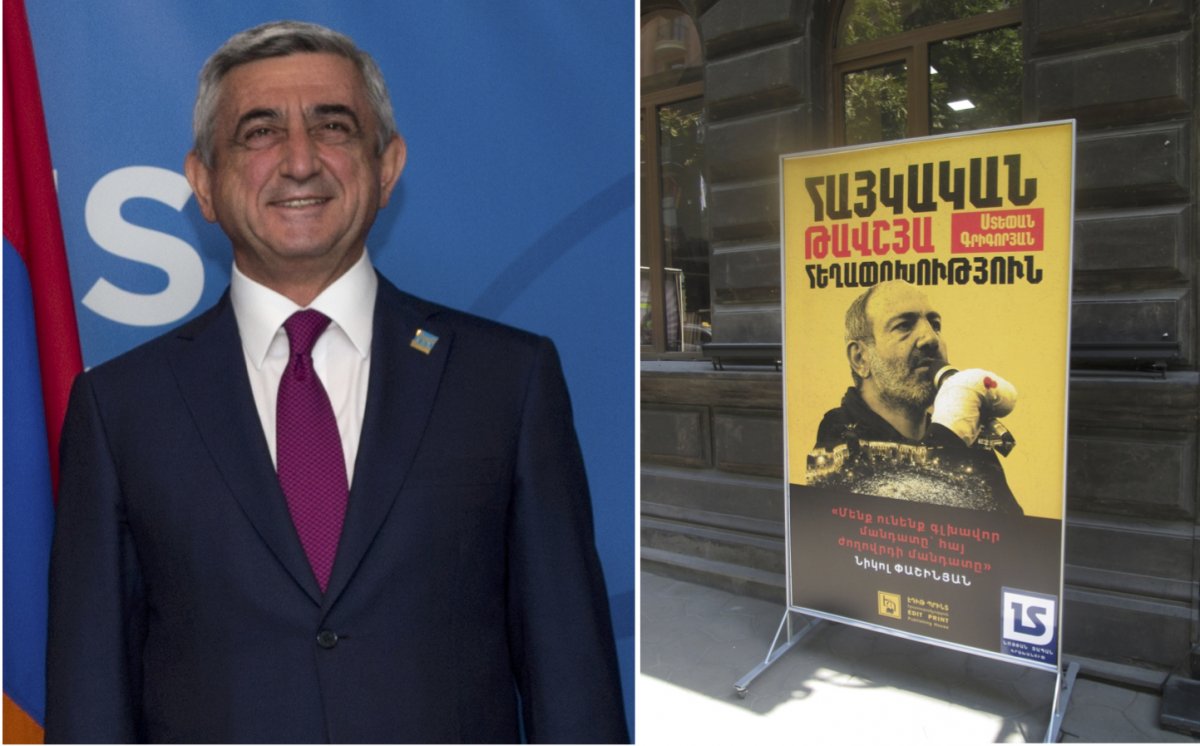

President Serzh Sargsyan at a NATO meeting in 2014 (left). A poster featuring Armenian revolutionary leader and now Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in 2018 (right) [photo by author].

The opposition, led by Ter-Petrosyan and a young journalist-turned-politician named Nikol Pashinyan, initiated mass demonstrations in Yerevan. Confrontation turned into open conflict between police and protestors. Tensions reached a boiling point on March 1 when violent clashes left eight protestors and two police dead. The government declared a state of emergency that day.

The events of March 1 traumatized Armenian society and cast doubt over the legitimacy of the newly elected president. To heal the country, Sargsyan took a conciliatory position toward the opposition. The media environment and room for open political exchange expanded greatly under his tenure (including a space for political comedy).

Protests following the 2008 presidential election at the Opera Square in Yerevan.

Nonetheless, Armenia’s persistent opposition combined with the liberalized political environment, ongoing socioeconomic problems, and the impact of the global recession to sustain protests throughout Sargsyan’s tenure.

In 2011 and 2012, there were small-scale protests in Yerevan over street vending and the preservation of green space. Large demonstrations occurred in the aftermath of the presidential election in 2013, in which U.S.-born Raffi Hovannisian contested the results that handed a re-election victory to Sargsyan. In 2014, there were more large-scale demonstrations against a controversial pension reform plan. And in 2015, a hike in electricity prices sparked the Electric Yerevan protests.

Protesters in Mashtots Park in 2012 (left). Raffi Hovannisian in Yerevan’s Freedom Square in 2013 (right).

Protesters also took to the streets over the government’s proposed political reforms. In late 2015, Armenian voters approved new amendments to the constitution, moving the country from a presidential system to a parliamentary republic. Such a switch had already been implemented in neighboring Georgia, and the amendments were endorsed by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission.

However, the opposition argued that President Sargsyan would use the reform to prolong his rule and slip into the prime minister’s chair after leaving the presidency in 2018. Sargsyan dismissed such claims and in 2014 publicly vowed to retire from politics in 2018—a fateful pledge.

Revolution 2018

In September 2016, Sargsyan appointed a new prime minister, Karen Karapetyan, a former mayor of Yerevan and executive of ArmRosGazprom, a subsidiary of the Russian natural gas giant Gazprom. But in April 2018, Sargsyan confirmed that he would stay on as prime minister, reversing his 2014 pledge, while he demoted Karapetyan to the position of deputy prime minister. The abrupt volte-face prompted the beginning of a protest movement, led by oppositionist Nikol Pashinyan, calling for Sargsyan to step down.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in April 2018.

Pashinyan’s protest movement, known as the “Take a Step” initiative, began when he walked from the Armenian city of Gyumri to Yerevan. Students soon formed the protest’s core. Armenian political analysts expected this protest to fizzle quickly. However, it grew.

The protests soon approached the size of Karabakh Movement rallies and attracted Armenians of all kinds. Young people saw the demonstrations as a way to realize a better future, while older generations viewed it as a second chance after the Karabakh Movement failed to realize their hopes.

Sargsyan did not seem to recognize the seriousness of the situation. He had weathered protests in the past, but nothing approaching the scale of what would become known as the April, or Velvet, Revolution.

As the stalemate between Sargsyan and the demonstrators continued, public anxiety grew. Sargsyan called on Pashinyan for talks, but the latter insisted on using Sargsyan’s resignation as the basis for negotiation. Their brief meeting broke down, causing public apprehension. The government’s attempted arrest of Pashinyan only increased the intensity of the protests. Through the intervention of Karapetyan, the government released Pashinyan. Then, on April 23, one day before the annual commemoration of the 1915 genocide, Sargsyan relented and resigned from office.

Widely popular, Pashinyan then pushed to assume the position of prime minister with the aim of breaking the RPA’s monopoly on power and reforming the country’s election laws. At first, the RPA attempted to block Pashinyan’s efforts on the day of the scheduled vote.

Demonstrations in Yerevan, April 28, 2018.

They also attempted to paint Pashinyan as an anti-Russian provocateur, in the hope of soliciting support from Moscow. However, Russia, which acted with great restraint during the revolution, remained uninvolved. Pashinyan’s interviews on Russian TV and his pronouncements that Russian-Armenian relations would be “deepened” under his watch did much to reassure Moscow.

An intensification of public protest, accompanied by a general strike on May 2, forced the RPA to relent. Pashinyan secured the necessary votes to become Armenia’s new Prime Minister.

Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in 2018.

Pashinyan still faced a parliament dominated by hostile members of the former ruling elite. Limited in his ability to enact policy until fresh parliamentary elections, he endeavored to shore up his popular support by arresting several prominent oligarchs.

Pashinyan’s attempted seizure of former Defense Minister Mikael Harutyunyan and CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) chief Yuri Khachaturov were particularly upsetting to Moscow. Nonetheless, the prime minister has since developed a good working relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

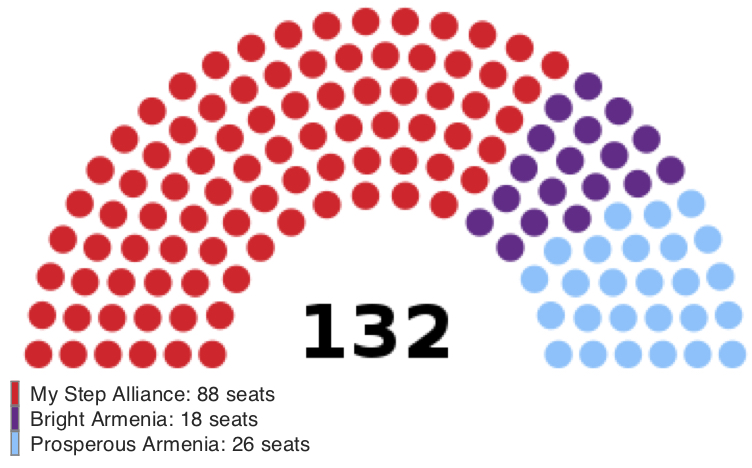

The Armenian parliamentary elections on December 9 reaffirmed and strengthened Pashinyan’s reform mandate. The Prime Minister’s My Step coalition swept the election by a staggering 70% of the vote, with Edmon Marukyan’s Bright Armenia party and Gagik Tsarukyan’s Prosperous Armenia party also entering parliament as minority parties. The biggest loser in the election was the former ruling RPA, which failed to attain enough votes to even enter parliament.

Public expectations of Pashinyan are at an all-time high, and his government will have difficulty meeting them.

There have already been public protest against the new government’s plan to scrap five ministries in order to downsize state bureaucracy. Fundamental problems such as unemployment, emigration, and poverty cannot be resolved overnight and require innovative and creative solutions.

Armenian National Assembly election results from 2018.

Nevertheless, the revolution has left an enduring mark on Armenia. Its revolution stands as an example of grassroots social change that opens the door for discussions on democratic development and economic justice throughout the region. Not only do Armenians feel empowered to make a difference, but people throughout post-Soviet Eurasia are watching developments in Yerevan with interest and a measure of envy.

For more on Armenia, see the Armenian Genocide; Nagorno-Karabakh; and Armenians, Turks, and the Genocide Question.

Leonidas T. Chrysanthopoulos, Caucasus Chronicles: Nation-Building and Diplomacy in Armenia, 1993-1994 (London: Gomidas Institute, 2006).

Gerard J. Libaridian, Armenia at the Crossroads, Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era: Essays, Interviews, and Speeches by the Leaders of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia (Watertown, MA: Blue Crane Books, 1991).

———. Modern Armenia: People, Nation, State (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2004).

Mark Malkasian, “Gha-ra-bagh!”: The Emergence of the National Democratic Movement in Armenia (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996).

Donald E. Miller and Lorna Touryan, Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Razmik Panossian, The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

Yuri Rost, Armenian Tragedy: An Eye-Witness Account of Human Conflict and Natural Disaster in Armenia and Azerbaijan, trans. Elizabeth Roberts (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990).