The hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca required of all Muslims, is one of the largest and most meaningful movements of people in the world. Last year, more than two million of the devout from all over the world travelled to Saudi Arabia to fulfill an Islamic duty. Yet as historian Eileen Kane details, the hajj has been shaped by interactions with Europe for several centuries. Though we don't think of it this way, the hajj is very much a European affair.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on Islamic communities around the world: Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Religious Divide in Iraq; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; Boko Haram; Feminism in Egypt; the Alawites and Syria; Turkey’s Politics; and The Meaning of “Muslim Fundamentalist.”

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East; Women in the Mideast and North Africa; and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

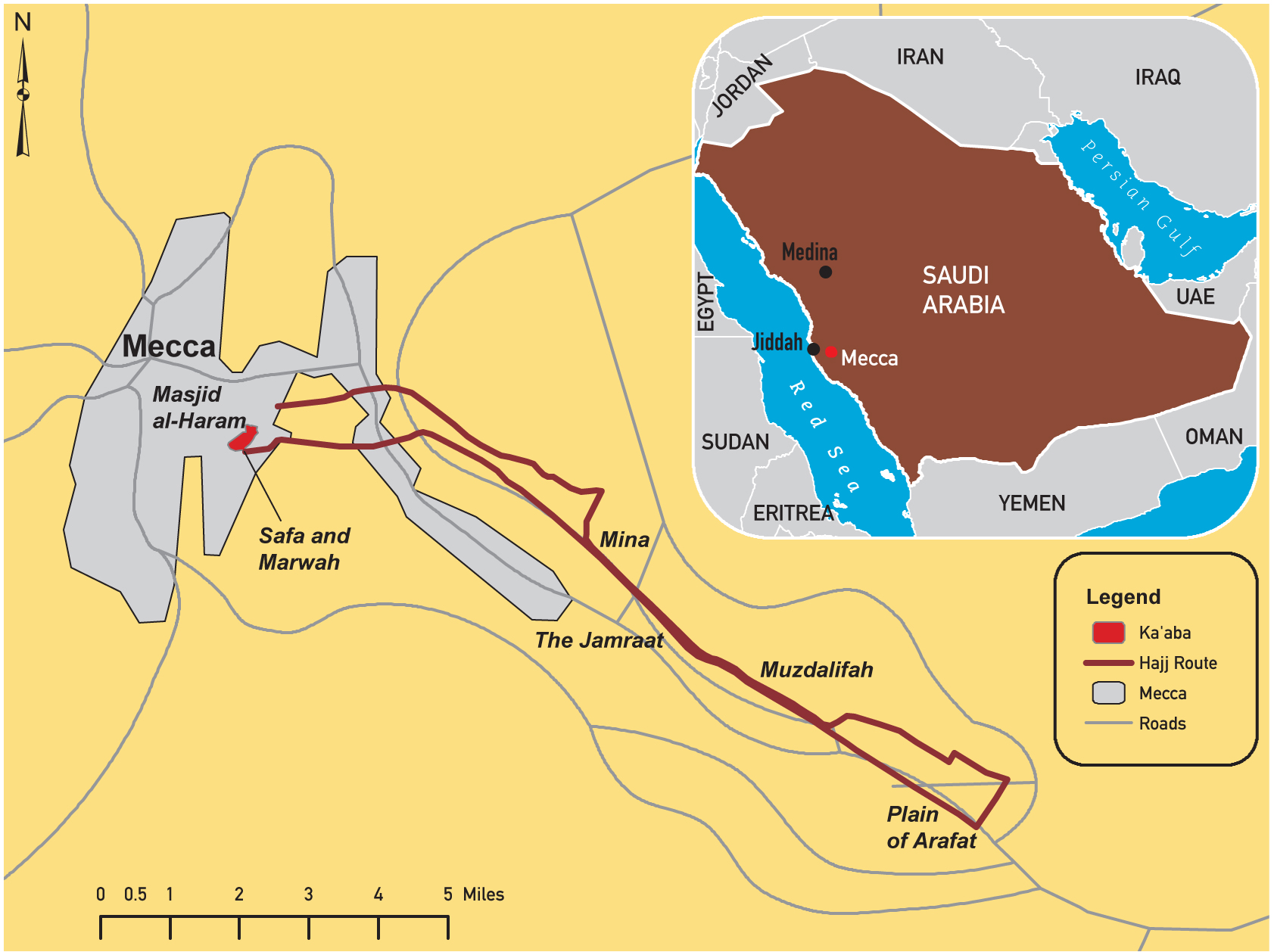

The hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, is a central ritual of the Muslim faith and one of the largest and oldest gatherings of people in the world. Pilgrims perform the hajj over three days during the last month of the Muslim lunar calendar (the date shifts every year, in reference to the Gregorian calendar).

Pilgrims carry out a specific sequence of rituals at a constellation of sites, recalling activities of the Prophet Muhammad, Islam’s seventh-century founder. Unlike other major world pilgrimages, the hajj is obligatory. In making the pilgrimage to Islam’s holiest city—Muhammad’s birthplace and the site of God’s revelations to him—Muslims fulfill one of the five pillars of their faith.

|

| Location of Mecca and the route of the hajj. |

For Saudi Arabia, the modern state that is home to Mecca, the hajj is both a lucrative industry (hajj revenues are 3% of GDP) and a mass event the kingdom must oversee at enormous cost. Last year the Saudis received about 2 million hajj pilgrims, a number kept artificially low by a quota system they introduced in the 1980s to control crushing crowds.

To manage and streamline the annual pilgrim traffic, the Saudi government has invested billions of dollars in a hajj infrastructure that includes two dedicated hajj air terminals, sanitation and health facilities in and around Mecca, as well as highways and tunnels connecting these sites.

|

| Aerial view of the Jamarat Bridge, 2009. |

Even so, last year’s hajj witnessed tragedy when a construction crane collapse in Mecca killed more than 100 and a stampede outside the city left several thousand dead.

A global phenomenon, the hajj must also be managed by the many nation-states that send citizens to Mecca each year as pilgrims. Today, the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims live everywhere. They negotiate access to Mecca through their countries of citizenship, which issue hajj visas based on the Saudi quota system. (Generally, the Saudis allot countries one spot on the hajj per 1,000 Muslim citizens.)

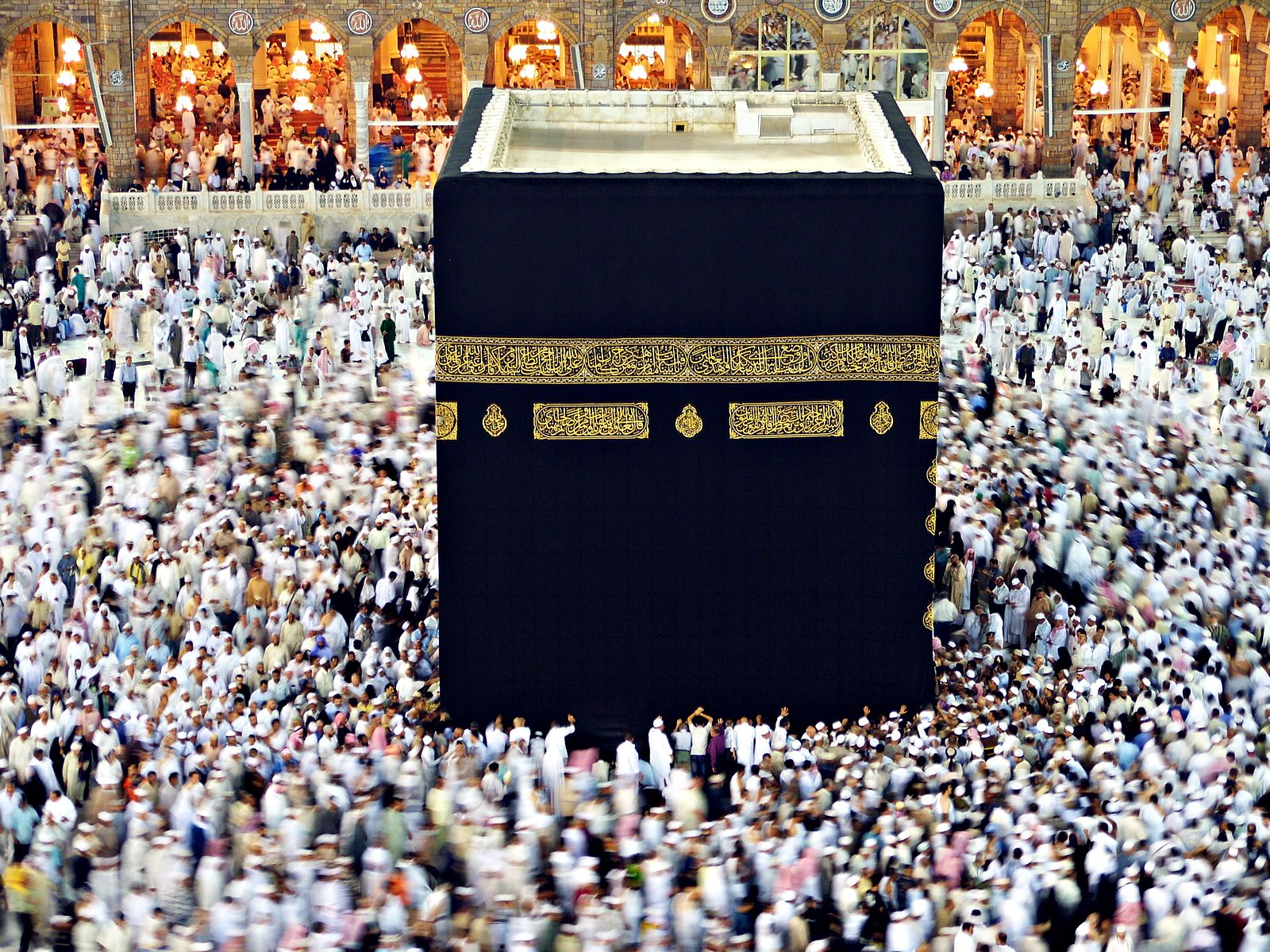

|

| Pilgrims circle the Kaaba at the Grand Mosque in Mecca, 2008. |

The process of deciding who gets a hajj visa—as well as how to ensure pilgrims’ safety, and how much states should subsidize the ritual—is complicated. In many countries, demand for hajj visas regularly exceeds supply, and there are long waiting lists, especially for those without political connections.

And, to a degree that many would find surprising, European nations are deeply connected to this annual Muslim event and have been for nearly two centuries.

At a time when mass Muslim migration to Europe is fueling divisive politics and reviving old fears and stereotypes about Islam as a conspiratorial faith that threatens “Western” ways of life, it is important to remember Europe’s earlier interest and involvement in the hajj and its role in shaping the modern history of this sacred Islamic ritual.

| Crowds travel to the Jamarat Bridge during the hajj, 2011. |

Europe as a Center of the Global Hajj

Europe today is a center of the global hajj both as a source of pilgrims and as a transportation hub.

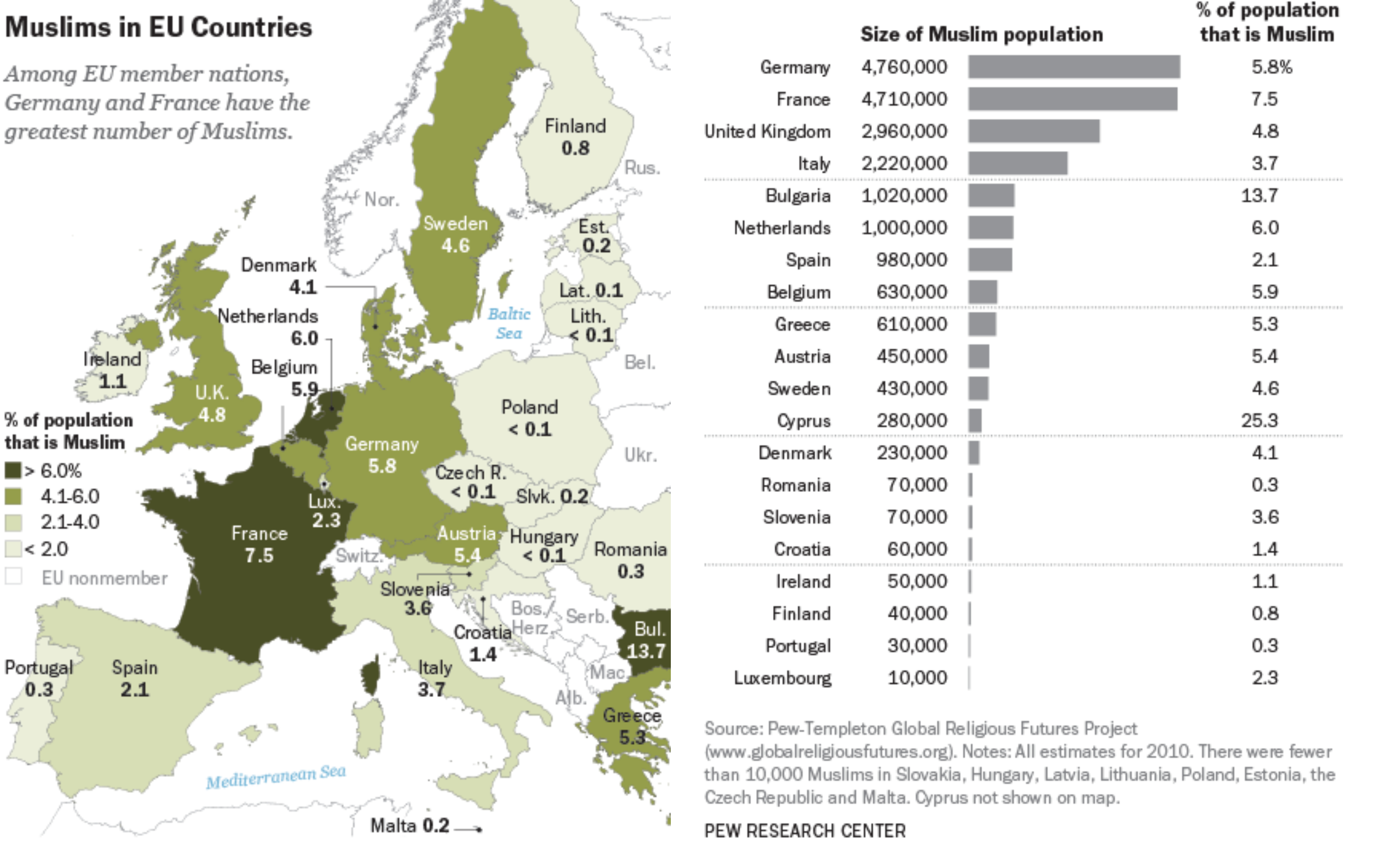

Large-scale Muslim immigration to Western Europe and the fall of communism in the east have caused Europe’s Muslim communities to grow. More than 40 million Muslims live in Europe today, representing 6% of the overall population.

At least 100,000 European citizens make the pilgrimage to Mecca annually, and their numbers are rising in line with the growth of Muslim communities in Europe, accelerated this past year by the arrival of over a million migrants and refugees from Afghanistan, the Middle East, and Africa.

In response to their integration into global hajj networks, European governments have been steadily, if rather quietly, sponsoring the pilgrimage.

Statistics on Muslim populations in the European Union.

In Britain, for instance, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2000 helped fund the British Hajj Delegation to provide consular support and medical services for its citizens on the ground in Saudi Arabia. Despite being officially secular, the French government posts a consul in Jeddah to help French nationals making the hajj. The most recent consul, a convert named Lewis Blaine, performed his job largely on motorbike, zipping around Mecca and the holy sites to assist French citizens.

Russia—which has 14 million Muslim citizens, the largest population of any European country—has perhaps done the most to support its citizen-hajj pilgrims. Since the early 2000s, under the Putin government, Russia’s Muslims have enjoyed discounted flights to Jeddah during hajj season on Aeroflot, the state airline. A state-created hajj liaison office arranges visas and transportation.

And in a new twist last year, after annexing Crimea from Ukraine, Russia offered Crimean Tatars generous hajj subsidies ($1000 per person, about a third of the cost of an economy package tour) in an obvious attempt to cultivate their loyalties toward Moscow and away from Kiev.

Launch of the British Hajj Consular Delegation, 2011 (left), and the British Hajj Delegation Clinic in Mecca, 2013 (right).

The Hajj during the Era of European Colonialism

Europe’s deep involvement with the hajj began during the era of global European imperialism.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Europe’s imperial powers had colonized much of Asia and almost all of Africa, and brought most of the world’s Muslims under colonial rule. (Of the world’s Muslim states, only Persia, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman Empire escaped European colonization.) In the decades before World War I, each of the leading imperial powers of the day—the British, Dutch, French, and Russians—ruled more Muslims in their empires than did any single independent Muslim state.

One effect of colonial domination of Muslim-majority lands was that the hajj came under European influence and control for the first time in history.

From its eighth-century beginnings after the birth of Islam, the Meccan pilgrimage had been performed almost exclusively under the patronage of Muslim rulers, through Muslim-ruled lands, and with the help of Muslim officials along the way. Hajj pilgrims’ ultimate destination—the Holy City of Mecca—was (and still is) closed to non-Muslims.

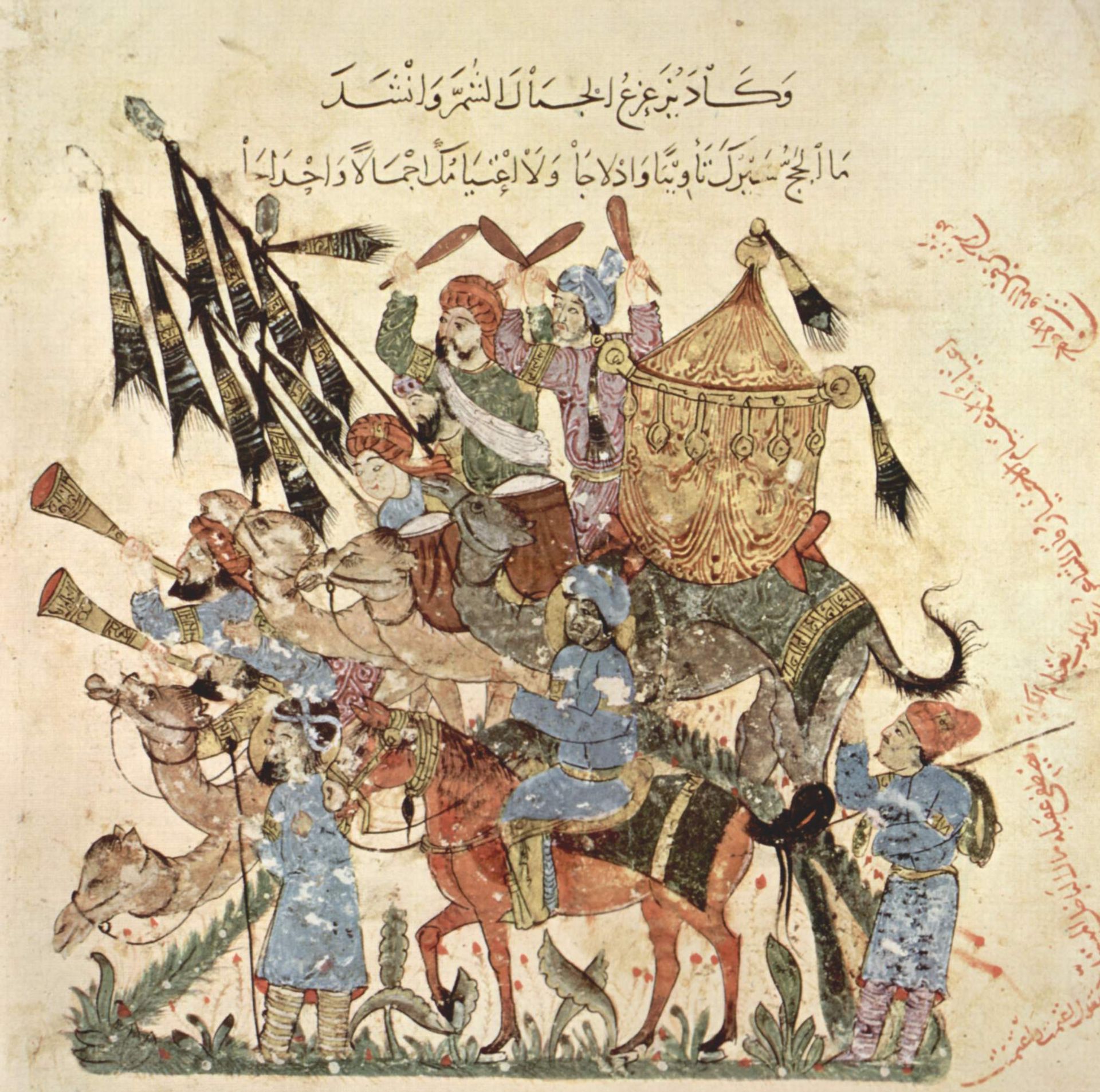

|

| Depiction of Mamluk-era caravan to Mecca by al-Hariri of Basra, 1237. |

Before the era of global European imperialism, Muslims made the Meccan pilgrimage under the auspices of Islamic empires. The Mamluk, Mughal, and Ottoman imperial governments all spent large sums to support hajj pilgrims making the long and often treacherous journey to Mecca through their empires, along land and sea routes.

The Ottomans were perhaps the most ambitious as hajj patrons. Each year, they sponsored imperial hajj caravans along major land routes to Mecca. These were enormous affairs of people and animals, led by military escort, and included as many as 50,000 pilgrims by the early 1800s.

To secure the caravan from attacks by bandits, and organize the hajj traffic under their supervision, the Ottomans fortified desert routes linking Damascus and Cairo to Mecca, building fortresses, wells, and cisterns along them.

|

| Pilgrim camp outside of Mecca, 1889. |

The Ottomans built their elaborate and expensive hajj infrastructure for both symbolic and strategic reasons. Hajj patronage was expected of the Ottoman sultan, as imperial ruler (after the sixteenth century) of the Muslim Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina and, with this, his claim to be “protector” of hajj pilgrims and “caliph of all Muslims.”

At the same time, the Ottomans were able to station troops and officials in their far-flung Arab provinces through the hajj infrastructure that they built and the ceremonies they staged around the annual caravans. They were also able to demonstrate the sultan-caliph's power and benevolence to local subject populations, as well as foreign Muslims.

This situation slowly began to change in the sixteenth century. As Europeans pushed into the Indian Ocean and parts of Asia, they conquered Muslim-majority lands and brought long stretches of traditional hajj routes under their direct control. As European empires grew, especially in the nineteenth-century, so did their interest and involvement in the hajj.

|

| Ottoman construction of the Hijaz Railway connecting Damascus to Medina, 1908. |

By the turn of the 20th century, most hajj pilgrims who showed up in Mecca were colonial subjects. They arrived in unprecedented numbers—as many as 300,000 a year—due to the global mobility revolution that European imperialism had also brought.

Across European colonies, the introduction of railroads and steamships had transformed the Meccan pilgrimage from a small-scale ritual performed mainly by elites into a mass annual event dominated by the rural poor, who packed onto the decks of Arabia-bound steamers on third- and fourth-class tickets. Their wretchedness at the hands of greedy ship captains made headlines in Europe, and provided the moral scandal at the heart of Joseph Conrad’s 1900 novel Lord Jim.

Sponsoring the Hajj

Having inherited a hajj tradition with their colonial conquests, Europe’s imperial powers had to decide what to do with it.

In the mid-nineteenth century, as hajj traffic between European colonies and Mecca began to grow, colonial officials were essentially of two minds about the hajj. At a time of growing anxiety about burgeoning Islamic political movements as a threat to empire, and fears of the hajj as a spreader of cholera and other infectious diseases, some suggested banning the hajj.

This was especially true after 1865, the year a massive cholera outbreak in Mecca became a global epidemic, spread far and wide by dispersing crowds of hajj pilgrims. After this epidemic—which killed more than 200,000 people worldwide in cities as far away as New York City—the European powers convened the first in a series of conferences that identified the hajj as a sanitary and security threat to empire. But attempts to ban the hajj proved impossible: as a pillar of Islam, and a duty for Muslims, the hajj could not be easily banned or stopped.

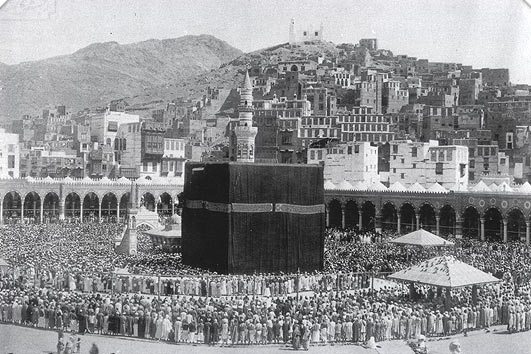

|

| The Grand Mosque and the Kaaba, 1907. |

Increasingly, as European control of Muslim populations grew over the nineteenth century, colonial officials began to see potential benefits in sponsoring rather than restricting or prohibiting the hajj. In the early 1800s, colonial officials began to experiment with hajj patronage as a way to win the support of recently colonized Muslim subjects, while also monitoring their contacts with Muslims from other parts of the world.

In the Russian-ruled Caucasus, tsarist officials in the 1840s started subsidizing hajj journeys for local Muslim elites they were trying to integrate into the emerging Russian administration. Similarly, in French West Africa in the early 1850s, the colonial government offered to pay for the hajj trips of select “friends of the colonial regime,” as part of a broader effort to advertise the toleration of French colonial rule.

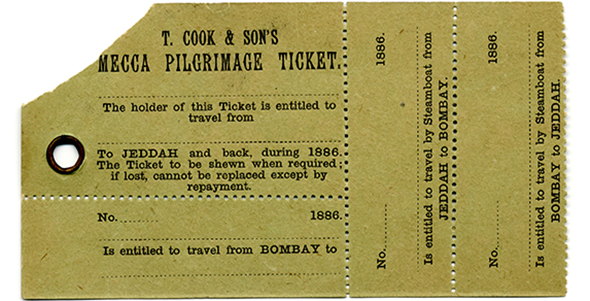

By the end of the nineteenth century, and for various reasons related to the desire to preserve empire and cultivate Muslim loyalties, all of the European powers began to sponsor the hajj. They subsidized travel between their colonies and Arabia during hajj season, opened foreign consulates along routes to Mecca, and passed new laws to protect pilgrims from physical harm and financial scams.

|

| 19th century British hajj ticket granting travel from Bombay to Jeddah. |

By the eve of World War I, European empires were involved in virtually all aspects of the hajj. Most Muslims would have found it impossible to make the Meccan pilgrimage in this era without interacting with European officials.

In Jeddah, the Dutch had set up a multi-service “Hajj Bureau.” The British ran a medical dispensary out of their consulate, run by the vice-consul, a Muslim doctor and British subject from India. And European doctors and nurses staffed the two main quarantine facilities set up to screen hajj pilgrims in El Tor (at the bottom of the Sinai peninsula) and on Kamaran Island (in the Red Sea).

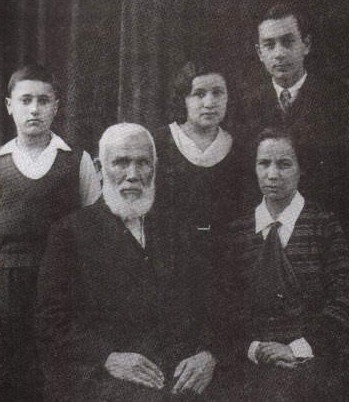

|

| Abdürreşid Ibrahim and his children. |

By sponsoring the hajj, European colonial powers were not simply trying to control it or contain the problems it created as a mass, annual movement of people. Instead, they were seizing an opportunity created by imperial conquests to tap into and co-opt the hajj, a global Islamic network, as a mechanism of imperial integration and expansion.

Through sponsorship, they sought to turn the hajj into an instrument of imperial integration. This was part of the broader process underway across European empires over the nineteenth century through which colonial governments institutionalized Islam and Islamic practices to advance their own imperial agendas.

European involvement in the hajj shocked many Muslim observers, who did not expect to be greeted in Ottoman Arabia by Europeans. Abdürreşid Ibrahim, the pan-Islamic intellectual and activist from Russia, was surprised when he showed up at the Kamaran quarantine station in 1908 and was greeted at the door of the disinfection building by a Christian woman. “Aren’t we in Ottoman territory?” his equally stunned travel companion asked him, to which he replied, “I don’t know.”

Europe and the Hajj, Lessons from the Past

In many ways, the hajj as we know it today bears little resemblance to its early twentieth-century counterpart. Airplanes long ago replaced sea and rail travel and transformed the itinerary of the hajj from a multi-site, months-long journey into a rapid, direct journey between home and Mecca.

A time traveler from 1900 would barely recognize Mecca: the Saudis have bulldozed Ottoman-era buildings and holy tombs around the city to make space for new shopping malls and luxury hotels. And today’s hajj crowds number in the millions, not the hundreds of thousands.

|

| Construction surrounding the Grand Mosque in Mecca, 2010. |

And yet, in an interesting parallel, the hajj today has again become a European phenomenon, as a result of global events and processes connected to European imperialism. Post-colonial migrations since the mid-twentieth century, the result of various push and pull factors, have brought millions of Muslims from former colonies to the European continent.

At the same time, the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the 1990s—hailed by many as the belated collapse of the last of the European empires—also freed millions of Muslims from state-mandated atheism and brought about a resurgence of Islam in Russia and surrounding former communist states.

Major European airports are now hubs along global hajj routes. In the days leading up the scheduled hajj rituals in Arabia, at airport departure gates in London, Berlin, Paris, and Moscow, crowds of Muslim pilgrims gather and pray before boarding flights bound for Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport.

Pilgrims arriving by ferry to Jeddah Port, 1957 (left) versus the contemporary Hajj Terminal of the King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah (right).

As today’s European states grapple with their own inheritance of a hajj tradition and how best to manage it, history can offer lessons as well as cautionary tales. The history of how Europe’s imperial powers embraced hajj patronage as part of their broader efforts to integrate Muslim populations in their empire has resonance today.

The case of the Russian Empire is perhaps most relevant to the situation of today’s European states. For the British, Dutch, and French empires, the hajj was largely an external issue, located in far-away overseas colonies, and not a domestic matter. Russia was different. A land-based empire, Russia had large Muslim populations living inside its borders, and hajj routes that cut through its central Slavic-speaking lands and busy Black Sea ports, and so it had both internal and external interests in the hajj.

For Russia, then, the hajj was not a matter limited to faraway regions and populations, invisible at home and separate from domestic issues. Instead, it was a highly visible, mass, annual event that happened largely within the empire’s borders, and was bound up with domestic issues such as state revenues, identity politics, and the integration of Russia’s 20-million-strong Muslim population (about 15% of the empire’s overall population in 1900).

In the early twentieth century, Russia struggled to reconcile its historic identity as an Orthodox Christian empire with the reality of its large and increasingly mobile Muslim populations, whose loyalties, it feared, may have belonged to the neighboring Ottoman sultan, not the tsar.

Many Russian officials wanted to restrict the hajj for many reasons. But how could they do this without appearing to intervene in Muslim practice and violate religious freedom? Conversely, how could they extend patronage to the hajj without upsetting the Russian Orthodox Church and losing its crucial institutional support for the regime?

Many of these same questions confront European officials, including in Russia, as they struggle to manage the hajj and accept it as part of their evolving national cultures. These are not so much new questions as old ones, rooted in Europe’s colonial past and made urgent for the European powers during the first wave of globalization in the late nineteenth century.

By exploring Europe’s overlooked, ambivalent, and complex role in the history of the hajj, we can begin to see that present-day discussions of Islam in Europe have a deeper history, and that perceptions about Muslims today are in many ways colored by stereotypes and prejudices refined in the late nineteenth century.

For instance, many European colonial officials in the early 1900s feared Mecca was a center of clandestine, conspiratorial, and anticolonial plotting. But no great anticolonial revolt was ever plotted in Mecca. And firsthand accounts by more than one Pan-Islamic activist reveal how disappointed they were by hajj pilgrims’ indifference to politics. Abdürreşid Ibrahim, a leading Pan-Islamic thinker and activist, lamented that he was unable to engage the simple, pious Muslims he met in Mecca in political discussion.

It remains to be seen how Europe will adapt to its new and growing role as a center of the global hajj. The context today is very different, and yet there are lessons to be drawn from history. The European embrace of hajj patronage was certainly opportunistic and imperialistic; the aim was to protect empire and, by accommodating Islam, subdue and integrate Muslim colonial subjects.

At the same time, there was a certain optimism to this policy that we should note: European officials did not simply fear Islam and its global dimensions, exemplified in the circular migration of Muslims between the colonies and Mecca. In the Russian case especially, there was a widespread belief that the Islamic inheritance of the hajj offered opportunities, not just dangers, and could be remade, not just suppressed, into a Russian tradition.

Today the hajj raises difficult questions for European nations that seek to reconcile national, secular identities with a need to respect the religious freedom of large and growing numbers of Muslim citizens, while also developing new strategies for integrating these citizens into the nation.

Bianchi, Robert R. Guests of God: Pilgrimage and Politics in the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Kane, Eileen. Russian Hajj: Empire and the Pilgrimage to Mecca. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Lecocq, Baz and Gregory Mann. “Between Empire, Umma, and the Muslim Third World: The French Union and African Pilgrims to Mecca, 1946-1958,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 27/2, 2007.

Peer, Basharat. “Modern Mecca: The Transformation of a Holy City,” The New Yorker, April 16, 2012.

Peters, F.E. The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Robinson, David. “France as a Muslim Power in West Africa,” Africa Today, 46, 3/4, 1999.

Slight, John. The British Empire and the Hajj, 1865-1956. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Taglicozzo, Eric and Shawkat M. Toorawa, eds. The Hajj: Pilgrimage in Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.