For over 600 years, the Ottoman Empire stood as one of the most resilient empires in world history. Its longevity was largely a function of its pragmatic approach to governance, especially during times of crisis.

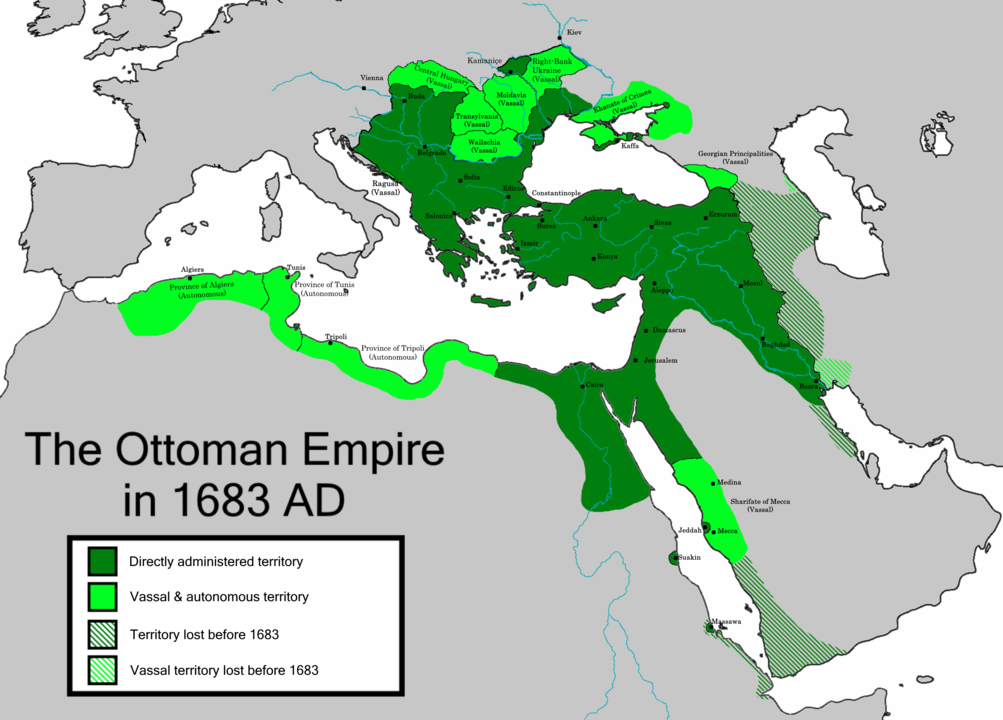

The Ottoman Empire at its greatest extent in Europe, under Sultan Mehmed IV, 1683.

Among the biggest crises that the Ottomans faced in their efforts to rule over an expansive territory that included much of the Middle East, North Africa, and southeastern Europe were those brought on by pandemics. Ottoman subjects would endure pandemics from their earliest beginnings in the fourteenth century right through their involvement in World War I, which ultimately contributed to the empire’s collapse.

As the COVID-19 pandemic focuses public attention on world governments’ handling of the current global health crisis, it is worth reflecting on how one of the most important and long-lasting empires in world history responded to some of the most devastating pandemics known to humankind. What follows is a quick overview of the Ottoman Empire’s experience with pandemics of plague, cholera, and influenza.

Plague

Early Ottoman expansion beyond northwest Anatolia, where the Ottoman state originated, occurred in the context of the Black Death, which ravaged Europe and the Mediterranean world during the early fourteenth century as part of the Second Plague Pandemic. Whether the Black Death facilitated early Ottoman expansion into the Balkans and central Anatolia by disproportionately affecting the Ottomans’ rivals remains a matter of controversy.

What is clear, however, is that, in the centuries that followed, Ottoman state formation had to contend with the reality of recurring outbreaks of plague. Ottoman expansion brought increased long-distance trade that contributed to the spread of plague within the empire by connecting people and pathogens from across the world.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the Ottomans had also developed a greater ability to promote public health, particularly by encouraging cleanliness in urban spaces, as Ottoman officials began embracing new understandings about the relationship between ecology and disease.

Indeed, this earlier experience with combating plague served the Ottomans well as they entered the nineteenth century, when they faced, during the first half of the century, recurring outbreaks of plague associated with the final years of the Second Plague Pandemic.

By the end of the 19th century the Ottomans were confronted with the threat of plague once more, this time in the form of the Third Plague Pandemic, which spread much more rapidly across the world than previous plague pandemics due to modern modes of transportation, such as steamships and trains. By that time, though, the Ottomans had already developed an extensive public health infrastructure that left them well-positioned to face this renewed threat of plague.

Ironically enough, however, the existence of that public health infrastructure owed its existence less to the Ottoman Empire’s past experiences with plague and more to its experience confronting pandemics brought on by a completely different disease: cholera.

Cholera

While plague shaped much of Ottoman history over a longer period of time, the Ottoman experience with epidemic diseases in the 19th century was dominated by recurring pandemics of cholera. Cholera, unlike plague, was a completely new disease for which the Ottomans, like much of the world for most of the nineteenth century, initially had imperfect knowledge.

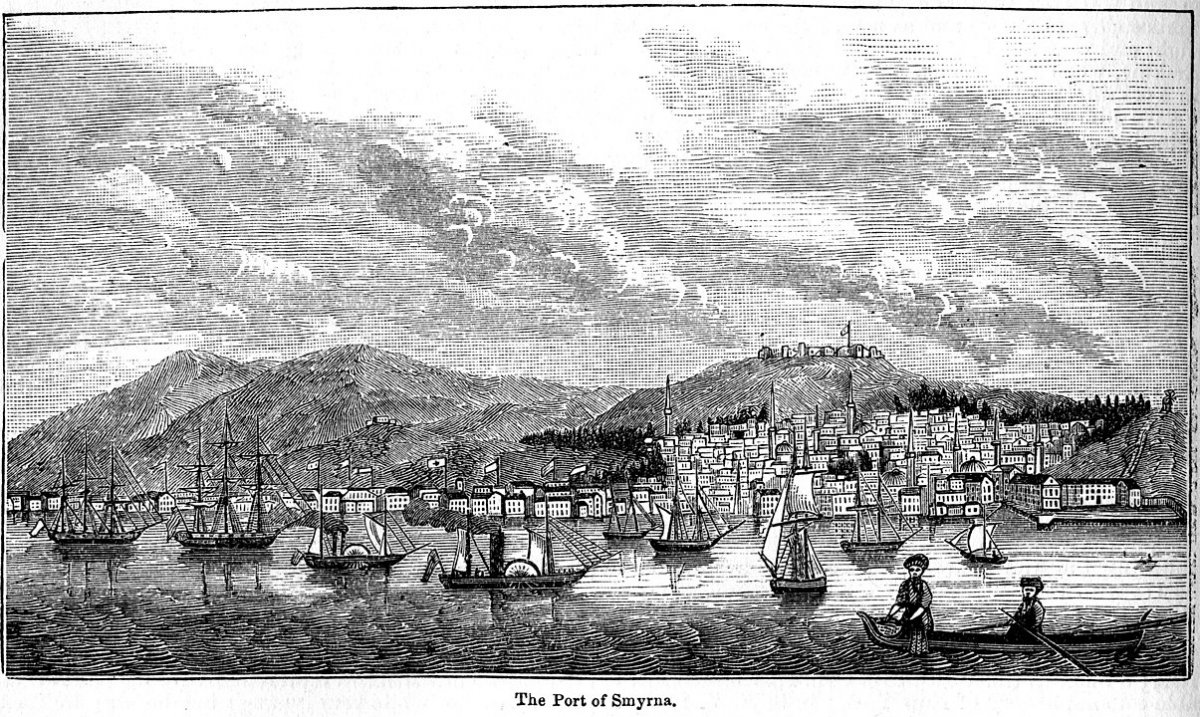

The disease, which is endemic to India, appears to have first entered Ottoman territory in 1821 by maritime routes that connected the Ottoman city of Basra to India through the Persian Gulf. Over the course of the nineteenth century, other routes of transmission quickly emerged, as commerce, migration, troop movements, and religious pilgrimage (particularly to Ottoman-controlled Mecca and Medina) created various pathways for cholera to spread within the empire.

Faced with this challenge, over the course of the nineteenth century the Ottomans developed a vast network of quarantine stations along various ports of entry to isolate individuals who were infected or suspected of being infected with cholera. Muslim pilgrims, particularly those from British India and neighboring Qajar Iran, were regularly subjected to scrutiny and surveillance by Ottoman officials during cholera pandemics.

Pilgrims and merchants complained about Ottoman quarantines especially when they seemed ineffective at containing cholera. Frustrated European government officials (particularly those from Britain) regularly used international sanitary conferences as venues not only for airing grievances about the obstacles that Ottoman quarantines created for commerce, but for arguing for the necessity of placing Ottoman quarantine protocols under greater international scrutiny.

Despite such challenges, however, the Ottomans never fully abandoned their use of quarantines, even as they devoted considerable energy toward improving the availability of clean water within the empire once the role of water in cholera’s transmission had been definitively proven.

Cholera patients arriving in Constantinople in 1912, during the Balkan Wars.

After all, for the Ottomans, quarantines were useful for more than just disease containment: they provided the state with a greater ability to monitor the movement of people and to assert sovereignty over borders in age of increasing European meddling in Ottoman affairs.

Needless to say, though, quarantines were just as unpopular in the Ottoman Empire as they are today. People from all walks of life became quite adept at evading Ottoman quarantine measures by smuggling goods, exploiting loopholes in international sanitary agreements, and, in some cases, openly rebelling against Ottoman quarantine officials.

Influenza

The Ottomans would rely on the public health infrastructure that they developed over the course of the nineteenth century to face a new public health crisis that emerged at the tail end of their involvement in World War I: the Influenza Pandemic of 1918.

The Turkish Red Crescent First-Aid Unit during World War I.

The war itself proved to be the biggest crisis in the empire’s history and ultimately contributed to the empire’s collapse by placing incredible stress on its human and material resources. During the course of the war, the empire’s public health infrastructure was likewise put under immense stress, as a large number of doctors were attached to the military, making it increasingly difficult for the state to meet civilian medical needs.

Unfortunately, the effects of the Influenza Pandemic on the Ottoman Empire are not yet fully understood (especially outside the imperial capital). However, when influenza reached Ottoman territory (possibly from Europe), one way that the Ottoman state attempted to offset shortages in medical staff was by banning certain public gatherings and closing schools, government orders that were not always followed by Ottoman subjects, much to the frustration of state officials.

Sources for Further Reading:

Yaron Ayalon, Natural Disasters in the Ottoman Empire: Plague, Famine, and Other Misfortunes (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Isacar A. Bolaños, “The Ottomans During the Global Crises of Cholera and Plague: The View from Iraq and the Gulf,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 51 (2019): 603-620.

Edna Bonhomme, “Plague in Eighteenth-Century Cairo: In Search of Burial and Memorial Sites,” in Plague and Contagion in the Islamic Mediterranean, ed. Nükhet Varlık (Kalamazoo, MI: Arc Humanities Press, 2017), 199-220.

Birsen Bulmuş, Plague, Quarantines, and Geopolitics in the Ottoman Empire (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012)

Michael Christopher Low, “Ottoman Infrastructures of the Saudi Hydro-State: The Technopolitics of Pilgrimage and Potable Water in the Hijaz,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 57 (2015): 942-974.

Andrew Robarts, Migration and Disease in the Black Sea Region: Ottoman-Russian Relations in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017)

Gülden Sariyildiz and Oya Dağlar Macar, “Cholera, Pilgrimage, and International Politics of Sanitation: The Quarantine Station on the Island of Kamara,” in Plague and Contagion in the Islamic Mediterranean, ed. Nükhet Varlık (Kalamazoo, MI: Arc Humanities Press, 2017), 243-274.

M. Kemal Temel, “The 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ Pandemic in the Ottoman Capital, Istanbul,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 37 (2020): 195-231.

Nükhet Varlik, Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World: The Ottoman Experience, 1347-1600 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Murat Yolun and Metin Kopar, “The Impact of the Spanish Influenza on the Ottoman Empire,” Belletin 79 (2015): 1099-1120.