For many Americans, the “rise” of China over the past two decades is primarily measured in economic terms and is seen by many as an economic threat. For many Africans, however, the rise of China has meant investments, loans, and an alternative path to economic development than the one offered by Western institutions. This month historian Ousman Murzik Kobo looks at the long-term relationship between China and Africa, examines its origins in the Cold War, and questions whether these ties with China are good for Africa or simply another form of colonialism.

For more on the recent history of Africa, please see these articles on Nile River Tensions, Politics in Senegal, the Darfur Conflict, Piracy in Somalia, Violence and Politics in Kenya, Women in Zimbabwe, and Sport in South Africa.

For more on East Asia, readers may also be interested in these Origins articles on Japan, North Korea, and Taiwan.

Over the past generation, Americans have observed China’s emergence with a mixture of excitement and anxiety. On one hand, huge new markets have opened to American companies; on the other, Chinese producers have created stiff competition.

Nowhere has China’s emergence been more dramatic than in Africa. Since 2000, China’s economic ties with Africa have increased exponentially. As of May 2012, China is Africa's largest trading partner, surpassing the United States and Europe. Trade between Africa and Beijing grew from $10 billion in 2000 to over $114 billion in 2010, and a year later it reached $166 billion. At the same time, China received about 13 percent of Africa’s global trade in 2010.

By 2010, China’s investment in Africa reached $40 billion. Although only 4 percent of China’s global investment, this figure is projected to reach 10 percent in 2030.

As a result of its intense trade with China, Africa registered 5.8 percent economic growth in 2007, its highest level in recent history. From 2000 to 2009, China also forgave poor African countries almost $3 billion in debt, more than the Western world’s total African debt forgiveness during the same period.

Some in the Western media call this bourgeoning Sino-African economic relationship a new form of colonialism. British journalist Justin Rowlatt produced a documentary for the BBC in 2011 titled “The Chinese are Coming.” Scenes in the program ranged from Chinese construction workers in Angola to Chinese poultry farmers producing genetically modified chickens (described on the program as “inflated chickens”) in Zambia, driving local poultry farmers out of business.

The catchy title and menacing themes echo dire warnings from some African academics, Western media, and policymakers about China’s insatiable appetite for land, markets, and natural resources.

As the South African Pambazuka News reminded readers in a 2006 editorial, “Almost every African country today bears examples of China’s emerging presence, from oil fields in the east, to farms in the south, and mines in the center of the continent.”

An estimated 800,000 Chinese work in Africa today. Chinese-run farms in Zambia supply vegetables sold in Lusaka’s street markets and Chinese companies have a virtual monopoly on the construction business in Botswana.

Historical precedents, including both China’s and Africa’s position vis-à-vis Western nations, provide important context for understanding the trajectory of the contemporary relationship between Africa and China.

China, Africa, and the Cold War

Explaining the historical relationship between China and Africa, Lu Shaye, the director-general of Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Department of African Affairs noted that “Sino-African ties can be traced back to more than 2,000 years ago.”

He is probably right. Archeological evidence from the ruins of ancient Zimbabwe and coastal eastern and southern Africa suggest that commercial ties existed between China and Africa before the Common Era. The Silk Trade Routes (roughly 200 BCE-200 CE) included parts of northern and eastern African coasts. And the visit of the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta to China in the 14th century provides evidence of ongoing connections between the two regions.

But the origins of the relationship between modern Africa and modern China can be located in the 1950s, when colonial rule in Africa was ending and the Cold War was intensifying.

The Bandung Conference in Indonesia in 1955, attended by most of the developing world, marked the starting point. Many attendees were young African nationalists whose core agenda was eradicating colonialism and forging a common front to safeguard the sovereignty of emerging nations against Cold War politics.

The Bandung Conference was followed by a series of conferences that culminated in the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. By this time, most of Africa had gained independence from European colonial rule and had joined the movement.

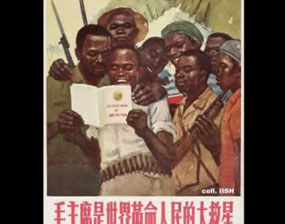

As a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and the largest member of the non-aligned group, China emerged as the de facto leader of the developing world. Although a communist nation, China declared both the Soviet Union and the U.S.-led Western powers neo-colonialists. China presented itself to the developing world as an alternative ideological partner that shared the experience of colonial domination and exploitation.

A major refrain in China’s foreign policy statements even today is reference to the historical experience of humiliation by the West and Imperial Japan. Indeed, at the Bandung Conference, China declared its intent to help liberation fighters throughout the world, and this became the hallmark of China’s Africa policy from the 1950s to the end of the Cold War in 1990.

During this period, China offered military intelligence, weapons, and training to freedom fighters in Algeria, Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, and Namibia. Even the African National Congress and the Pan African Congress of South Africa received some support in their struggles against apartheid South Africa. This policy appealed to many young African nationalists, including Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Jamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, and King Hasan of Morocco.

Africa became a Cold War zone where China, the Soviet Union and the United States collided. The Congo Crises of 1961-1965 set the stage for Cold War politics in Africa and provide some clue to China’s interest in Africa during the first decade of independence.

Seeking for ways to compete with the superpowers for control over Congo’s copper resources crucial for military and civilian hardware, Mao Tse Tung remarked in 1964, “If we obtain Congo, we have obtained Africa. Congo is our passageway into Africa.”

China’s intention to help free Africa from the claws of colonialism was indisputable. For example, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, often considered the father of African liberation, invited Chinese military advisors to train freedom fighters from all corners of the continent between 1957 and his overthrow in 1966. Beijing also helped Ghana to secretly establish the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, which was dismantled in 1966.

As early as the 1960s, many African leaders considered China not only a political ally but also an economic partner with a development model sensitive to local cultures and conducive to the needs of societies that had limited foundation for industrialization. Despite China’s widespread famine and economic troubles during the Great Leap Forward, the Chinese model of gradual but rigorously planned industrialization appealed to many African leaders eager for development but aware of their limited technological capacity.

The “Ujamaa” (Swahili for “familyhood”) project implemented by Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, which emphasized collective farming and self-reliance, as well as Nkrumah’s plans to accelerate Ghana’s industrialization without sacrificing the agricultural sector were examples of African leaders’ attempts to emulate China. Ironically, just as the Great Leap Forward resulted in famine in China, the programs in Ghana and Tanzania resulted in severe food shortages and were subsequently abandoned.

During this era of Sino-African relations (late 1950s to early 1990s), China also offered direct economic assistance in the form of low-interest loans for public projects. The most important of these was the Tanzania-Zambia Railroad Project (TAZARA).

At a time when the world price of copper was very high, Zambia, a copper producer but a landlocked country, requested a $400 million loan from the World Bank in the late 1960s to build a railway linking the copper-producing region with the sea in Tanzania. But the World Bank rejected the project as too risky. China stepped in with a thirty-year interest-free loan and completed the project in 1975.

The TAZARA Railroad became the symbol of Beijing’s readiness to include economic activities in its relations with Africa, and served to convince Africans that China was not only a political ally but also a potential business partner capable of offering Africa what the West would not deliver.

The socialist-leaning Nyerere remarked at the signing ceremony in 1967 that “all the money in this world is either Red or Blue. I do not have my own Green money, so where can I get some from? I am not taking a cold war position. All I want is money to build [the project].”

Kenneth Kaunda, the capitalist-leaning president of Zambia, expressed his disappointment with the West more bluntly: “If the Western industrialized states do not shake off their apathy towards Africa, then the influence of the East will soon dominate the continent.” This prediction became a reality from the late 1990s. Meanwhile, China’s policy toward Africa during the Cold War remained focused on assisting the liberation of the continent from colonial rule and neo-colonial influences.

Interestingly, it was also in the course of helping African liberation that China faced its most uncomfortable diplomatic and military debacle in Africa. China had begun to establish closer relations with the United States after President Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972, and as a consequence found itself supporting Apartheid South Africa and the United States against the Soviets and Cuba in the Angolan civil war (1975-2002).

Having publicly condemned apartheid and Western imperialism for over two decades, China disappointed African leaders by unwittingly acting as the proxy for apartheid in the Angolan conflict that Chinese experts considered a stand-in war between China and the Soviet Union.

Most African countries cut off diplomatic relations with China in protest and Beijing briefly lost African support in the United Nations on the issue of Taiwan’s independence. In the end, the Soviet-backed faction in the civil war won decisively despite the massive support UNITA received from the United States, China, and South Africa—a double loss for China.

After this fiasco, China virtually retreated from Africa only to return after the Cold War—this time as a powerful trading partner.

China’s Interests in Africa after the Cold War

At the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, both the United States and Russia abandoned their African allies, and China stepped into the vacuum. In place of the ideological and military focus of the Cold War, China concentrated on developing economic relations, not only changing the African economic landscape but also transforming Africa’s relations with the West.

There is no doubt that China perceives Africa as a market and a source of raw materials (primarily oil and precious minerals) as well as agricultural products. Let’s begin with China’s interest in African oil since China’s booming industry depends on a stable supply.

Once the largest oil exporter in Asia, China became an importer in 1993, and is projected to import more than 45 percent of its oil by 2045. As of 2007, China imports about one-third of its oil from Africa, about 13 percent of Africa’s oil exports. The United States remained the largest net importer of African crude oil.

Considering the ongoing crisis in the Middle East, China is moving ahead of the rest of the world in positioning itself to exploit Africa’s oil resources. In a January 2007 article, Esther Pan noted: “China’s voracious demand for energy to feed its booming economy has led it to seek oil supplies from African countries including Sudan, Chad, Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of Congo.” Two weeks earlier the state-owned Chinese energy company, CNOOC Ltd., announced it would buy a 45 percent stake in an offshore oil field in Nigeria for $2.27 billion.

In addition to oil, Africa supplies a wide a variety of raw materials to China. China imports about 90 percent of its cobalt, 35 percent of its manganese, 30 percent of its tantalum, and 5 percent of its hardwood timber from Africa.

China also needs Africa’s political support in its conflict with Taiwan. Among the 55 African countries, only four have not established diplomatic relations with China: Burkina Faso, Gambia, Sao Tome and Principe, and the Kingdom of Swaziland. Besides these four, most of the African members of the UN, more than one-quarter of the UN’s 193 members, generally support China against Taiwan. In order to ensure this general support, Beijing built the $200 million African Union Headquarters at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

A Different Path to Development: The Appeal of China

Africa’s ties to China entail some significant benefits for Africa, but also significant costs. First, the benefits. At a time when structural adjustment policies pursued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have hampered Africa’s investment capability, many African leaders have come to see China as a better economic partner than the West.

China has offered Africa interest-free or low-interest loans. Unlike loans from the IMF and World Bank that often carry high interest and require expensive oversight and compliance reviews, the Chinese are sensitive to the economic predicaments facing Africa and offer practical solutions.

For example, in 2004, China offered Angola a $2 billion grant for the construction of railroads, schools, roads, hospitals, bridges, public buildings offices, and fiber-optic networks. Construction was undertaken by Chinese companies. In addition, Angola received another line of credit from China that was pegged at 1.5% over 17 years.

China’s policy of canceling debt to poor countries reinforces the perception that China is more willing to help Africa than the Western world. Sudan and Zimbabwe, generally considered the worst human rights violators on the continent, each host a large Chinese economic presence.

At Zimbabwe’s 25th Independence Anniversary, Robert Mugabe said, “We have turned east, where the sun rises, and given our back to the west, where the sun falls.” The IMF and the World Bank’s conditions, and the use of loans as political tools by powerful Western nations, had opened space for China to deal quite profitably with some of the more heinous regimes of continent.

Other African leaders are attracted to China not only because of its flexibility on African projects and loans, but also because of the speed with which Chinese businesses complete projects. As one Angolan leader remarked, “When the Chinese agree to embark on a project, they get it done at the stipulated date and stipulated cost.”

Sierra Leone’s ambassador to Beijing, Sahr Johnny similarly stated: “The Chinese are doing more than the G8 to make poverty history … If a country wanted to rebuild the stadium, we’d still be holding meetings! The Chinese just come in and do it. They don’t hold meetings about environmental impact assessment, human rights, bad governance and good governance. I’m not saying it’s right, just that Chinese investment is succeeding because they don’t set high benchmarks.”

A senior manager from the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa echoes this sentiment bluntly: “If you want concrete things you go to China. If you want to engage in endless discussion and discourse you go to the normal traditional donors.” Evidently, African countries prefer China’s unconditional aid rather than assistance from the West that insists on acceptable human rights practices, economic policy reform, or democratic governance.

Beijing’s policy of “noninterference in domestic affairs” also appeals to some African countries such as Sudan and Zimbabwe that are considered “rogue” regimes because of massive human rights violations.

Because China also stands accused by the Western world of violating its citizens’ rights, China finds common ground with these African nations and maintains that human rights are relative, and that countries should be allowed their own definitions and practices. In fact, China has argued that attempts by foreign nations to discuss democracy and human rights violate the rights of a sovereign country.

Some Chinese and African experts maintain that Beijing's approach is not significantly different from how any other country pursues its interests. David C. Kang, professor of government at Dartmouth College, writes, “The United States is highly selective about who we’re moral about. … We supported Pakistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia—huge human-rights violators—because we have other strategic interests. China’s not unique in cutting deals with bad governments and providing them arms.”

While Western media and political pundits tend to portray China as the winner-winner in Africa, it is clear that African leaders believe they benefit from their relationships with China, at least in the short run.

At any rate, they welcome the new investment opportunities as well as the broadening of the scope of trading partners that China presents. They do not have to deal only with the West, but can now shift to an economic giant that, while potentially exploitative, understands the dilemma of a weak economy.

Finally, China’s permanent UN Security Council membership attracts African members. China uses the threat of its veto in the Security Council to counter or water down sanctions against some African countries.

In return, African countries support China when criticized in the UN Human Rights Council, and overwhelmingly support China’s rejection of Taiwan’s independence. China also seeks African support on a number of other issues such as climate change and issues concerning the World Trade Organization.

Africa’s Dividends and China’s Dominance

The growing Chinese economic presence in Africa has created concern over how China operates on the continent. Many Africans accuse Chinese companies of underbidding local firms and not hiring Africans. Chinese infrastructure deals often stipulate that up to 70 percent of the labor must be Chinese. Even non-construction projects usually involve some material and technical assistance from China.

It is worth noting in this context that 70 percent of Africa’s exports to China come from the oil exporting countries: Angola, the Republic of Congo, South Africa, and Sudan. Another 15 percent of Africa’s exports to China consist of raw materials (timber and minerals). China’s exports to Africa are mostly manufactured goods (cell phones and computers, automobile parts, machinery, textiles).

Many Western critics and African academics argue that China’s exports are killing Africa’s industrialization programs, since Africa’s industrial goods cannot compete with Chinese goods either in China or in Africa.

For example, low-cost Chinese textiles and electronics attract African consumers but these low-cost imports compete with local industries. This is classic “dumping” that often collapses local infant industries and causes massive unemployment.

The South African textile sector, for instance, is believed to have laid off 50 percent of its labor force between 1996 and 2006 as a result of its inability to compete with Chinese imports.

Citing Chinese competition as the main cause of rising unemployment, in early 2006, the Congress of South African Trade Unions threatened to boycott anyone selling Chinese products. Only after the South African government raised these concerns did the Chinese government agree to impose quotas on its textile exports in order to encourage the local textile industry to recover.

Despite these tensions, immediate mutual benefits exist. For instance, the China Road and Bridge Corporation, a state enterprise, has built low-cost but high-quality roads, sports stadiums and office buildings in many African countries including Ghana, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In Zambia, China has invested nearly $170 million in the mining sector, previously abandoned as unprofitable, and plans to build a $200 million copper smelter at Zambia’s Chambezi Mine.

In Gabon, a Chinese consortium headed by the Chinese National Machinery and Equipment Import and Export Corporation (CEMEC) has been granted sole rights to exploit huge untapped iron ore reserves and to build a railway line to connect the mines with the coast, a project that had earlier been considered too risky by Western sponsors.

Some experts also believe that China’s engagements with Africa could stimulate economic growth and induce change on the continent.

Harry G. Broadman, a World Bank economist, wrote in 2006 that Chinese firms may provide African countries with a “chance to increase the volume, diversity, and worth of their exports.” But these benefits are contingent on African governments’ consistent efforts in implementing economic reforms “of basic market institutions, investment regulations, infrastructure, and tariffs.”

China in Africa: Neo-Colonialism or New Trading Opportunities?

During her visit to Zambia in June 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton remarked, “We saw that during colonial times, it is easy to come in, take out natural resources, pay off leaders and leave ... And when you leave, you don’t leave much behind for the people who are there. We don’t want to see a new colonialism in Africa.”

The historical inaccuracy in Clinton’s statement notwithstanding (colonial rulers did not “pay off” African leaders since African leaders had no leverage that required colonial authorities to bribe them), the trope of neo-colonialism reveals Western concern about China’s extensive presence in Africa.

Many fear that China’s investments and foreign aid to Africa are inconsistent with the generally accepted international norms of transparency and good governance. This concern is shared by many African leaders as well.

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao responded to similar accusations during a visit to seven African countries in June 2006 when he noted that, “The cap of ‘new colonialism’ should never be put on China. China had suffered about 110 years of colonialism since the Opium War in 1840. The Chinese people understand the pains brought about by colonialism and know colonialism should be battled against. This is one of the reasons that we have long been supporting liberation and revival of the African nations.”

Chinese official Lu Shaye made the point even more emphatically: “Some Westerners said China’s cooperation with African countries is a practice of ‘colonialism,’ while the African people said the West is re-colonizing Africa. Let’s see what colonialism is—grabbing resources with violence, enslaving African people, seizing land and destroying African culture. China helps some African countries build roads, bridges, hospitals and schools. We buy African resources with equivalent exchanges. China never interferes with other countries’ internal affairs, or imposes China’s culture and values, but communicates with the African countries on an equal basis. We support the African countries solving their problems independently.”

To a large extent his definition of colonialism is accurate. He is also accurate in suggesting that African leaders are much more skeptical about the intentions of Western powers in Africa than they are about China’s.

However, the mutual accusations of “neo-colonialism” reflect a growing competition between China and the United States for African resources, especially oil. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent upheaval throughout the Middle East, both China and the United States became dependent on African oil as each sought to diversify its supply lines away from the Middle Eastern crude.

The economic rivalry between China and the United States is therefore evident in Africa just as their military competition plays out in the Pacific. A report by U.S. think tanks, including the RAND Corporation, the Heritage Foundation, and the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations urge strategies to weaken China’s influence in Africa.

The AFRICOM (African Defense Force) established in 2007 is a clear example of the United States’ readiness to respond to terrorist activities in Africa. But it could also reflect attempts to reinforce U.S. military preeminence in Africa ahead of any possible Chinese military buildup on the pretext of defending Chinese economic investment.

While this potential competition may be interpreted as a new form of colonialism, it may provide African leaders with the opportunity for pitting one power against the other to maximize economic benefits. Competition between China and the West offers opportunities for Africa, but what seems lacking is African leaders’ ability to take advantage of these opportunities by developing their negotiation strategies.

The Sino-African Future

Since the China-Africa Summit of 2004, China has accelerated its relationship with Africa. This new relationship reflects China’s version of globalization. The United States perceives China’s economic expansion in Africa as a serious concern primarily because of Africa’s huge oil resources and geopolitical location.

For Africa, China offers significant opportunities but also worries. Unless African countries find ways of negotiating the complex webs of international politics, the continent will once again become a theater for imperial competition by proxy.

As a BBC commentator noted, “If there is one thing African states can learn through China, it is how to imagine their own future, explore new possibilities, and engage with the rest of the world while retaining control over the conditions of those engagements.” Or as Sarah Raine remarked in her book on Africa-China relations, the discourse is China and Africa, but the subtext is “China, Africa and the West.”

Chris Alden, China in Africa: Partner, Competitor or Hegemon? (African Arguments) Zed Books 2007

Chris Alden, “China in Africa,” Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, volume 47, Issue 3, 2005: 147-164

Deborah Brautigam, The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa, Oxford University Press, Reprint edition, 2011

Padraig Carmody, The New Scramble for Africa, Polity, 2011

Fantu Cheru and Cyril Obi (eds.) The Rise of China and India in Africa: Challenges, Opportunities and Critical Interventions (Africa Now), Zed Books, 2010

Stephanie Hanson, “China, Africa, and Oil,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 6, 2008

BS Michael and M Beuret, China Safari: on the Trail of Beijing's Expansion in Africa Cambridge University Press, 2010

Robert I. Rotberg, China into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, Brookings Institution Press, 2008

David H. Shinn and Joshua Eisenman, China and Africa: A Century of Engagement. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012

Ian Taylor, China's New Role in Africa, Lynne Rienner, 2010

Ian Taylor, “China's oil diplomacy in Africa,” International Affairs, volume 82, Issue 5, September 2006: 937–959

George T. Yu, “Sino-African Relations: A Survey,” Asian Survey, vol. 5, No. 7, Jul., 1965: 321-332