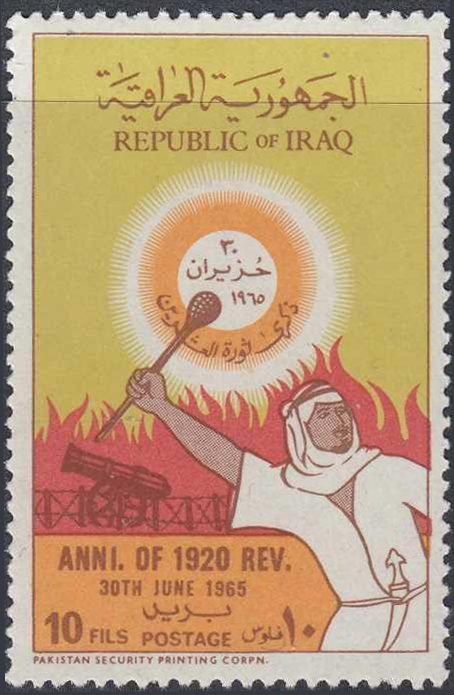

For many months in 1920, people all across Iraq rose up to fight the British military administration that had seized control of the country during the First World War. The popular uprising brought together Sunnis and Shi'is, elites and commoners, city dwellers and tribespeople. It caught the British by surprise, and changed the trajectory of modern Iraqi history.

Armed revolt broke out in the fertile plains south of Baghdad, as bands of tribespeople swept in from the desert to attack isolated British military outposts and destroy vital railway lines. These incursions continue to shape public memory of the uprising. For Iraqis and outsiders alike, the image of unexpected, violent resistance to European rule on the part of heroic mounted warriors epitomizes the 1920 "revolution."

Yet the foundation for the revolt had been laid by liberal and radical nationalists based in the cities. Together they forged a unified platform out of an assortment of patriotic and religious grievances. British officials had declared that they came as liberators from foreign oppression when they marched into Baghdad in March 1917, but three years later showed no sign of tolerating Iraqi self-government.

Nationalist leaders watched with increasing alarm as British officials tightened their grip on the country's irrigation system, food distribution network, labor conscription mechanisms, and tax collecting apparatus, making these institutions more efficient but skewing their operation to the advantage of local allies of the imperial authorities.

Towns and villages that resisted the imposition of the new order found themselves subjected to brutal punishment, most notably from the most advanced weapons technology of the day: bombs dropped from airplanes.

Popular anger at the indiscriminate use of aerial bombardment in the restive agricultural districts between Baghdad and the southern port city of Basra convinced nationalists in the capital that the moment was ripe for revolt. Oblivious to the seething rage in the southern provinces, British warplanes carried out a bombing campaign against one of the region's most influential clans in late May 1920.

Map of Iraq showing major areas of rebellion in 1920.

In the Shi'i theological and pilgrimage centers of Najaf and Karbala, senior religious scholars ('ulama) challenged the consolidation of British rule in the name of constitutionalism. Prominent figures in these two cities had supported the 1906 revolution in Iran, which had compelled the ruler to authorize elections for a constituent assembly to draft a constitution. The collapse of Iran's experiment in constitutional government motivated Iranian-born religious leaders in Najaf and Karbala to continue the campaign in post-Ottoman Iraq.

Nationalist organizations in Baghdad and Basra meanwhile stepped up their own demands that the British set up an elected representative assembly. These calls were echoed by influential Shi'i figures in the capital’s poorer neighborhoods, particularly the impoverished district outside the Kadhimiyyah shrine.

Encouraged by the positive response from Baghdadi Shi'is, a delegation of radical nationalists traveled to Najaf and Karbala to link up with proponents of constitutionalism in the country's Shi'i hierarchy. The most respected scholar in Najaf, Sayyid Muhammad Taqi al-Shirazi, issued a doctrinal edict (fatwa) calling on all Muslims to join the struggle against foreign domination.

Tribal chieftains in the region surrounding Najaf and Karbala who had recently adopted the Shi'i way of Islam immediately rallied to the call and drove British-led Indian troops out of several strategically situated southern towns. Captured soldiers were treated leniently, even as retreating British forces routinely set fire to the settlements they passed through and butchered the inhabitants.

By late July, Iraqi fighters had taken charge of most of the territory between Baghdad and Basra, aside from the pivotal city of Hilla where British commanders prepared to make a last stand on the road to the capital.

In an attempt to persuade tribespeople around Hilla to refrain from joining the revolt, British-led Indian troops launched raids into the countryside south of the city, which culminated in a counterattack to relieve the besieged garrison at the city of Kufa. The column's advance was stopped at the village of Raranjiya, where it suffered a costly defeat.

Revolt then spread to the northern farmlands around Baquba and Samarra. Anti-British fighters captured warehouses belonging to wealthy landowners, alienating the elite nationalists whose fortunes derived from estates in that region. Class-based tensions started to divide the liberal and radical wings of the independence movement.

RAF plane taking part in the British campaigns in Iraq.

At the same time, long-standing rivalries among tribal clans, a general reluctance to join the uprising on the part of residents of Baghdad, Basra and the northern city of Mosul, and British technological superiority sapped the momentum of the revolt. By late October the uprising had been crushed.

British officials reacted to the revolt by setting up an advisory council, thereby modifying the type of direct rule they had practiced earlier. Council members consisted almost entirely of well-to-do Sunnis drawn from the larger cities, leaving the Shi'i community unrepresented in deliberations over policy. Whatever administrative autonomy Najaf and Karbala had enjoyed was squelched.

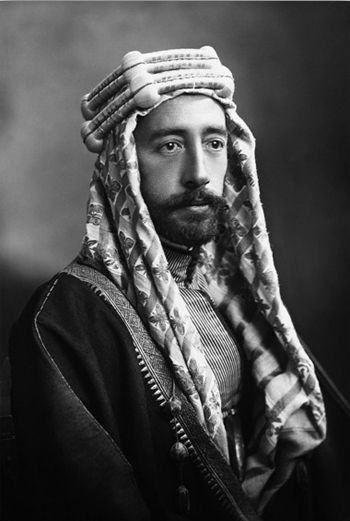

More important, the British invited a senior member of the Hashimi family of Mecca to become king of Iraq. Shi'i scholars had issued a similar invitation on behalf of the nationalist movement, but overt British patronage aligned the interests of the monarchy with those of the imperial authorities.

Over the ensuing century, the events of 1920 have been reshaped to suit shifting political purposes. Sunni-led regimes, most notably those of the Ba’ath Party era, erased the contributions of Shi'i leaders and gave credit for initiating the uprising to a secondary Sunni chieftain. Raranjiya was renamed Rustumiya, and, in the history, decisive battles were relocated away from predominantly Shi'i areas to such Sunni districts as Fallujah.

The autonomous administrations that were set up in Najaf, Karbala, Diwaniya and Baquba have been forgotten. The activities of radical nationalists in Baghdad, Basra, and Samarra remain obscure, while the exertions of local activists in the countryside go unrecognized.

Echoes of the revolt nevertheless reverberate in present-day Iraq. A radical militia that challenges the legitimacy of the post-Ba'athi order calls itself the 1920 Revolution Brigades. Widespread resentment against the permanent presence of foreign troops on Iraqi soil simmers beneath the surface.

Protests in 2019 and 2020 have called for the removal of foreign troops from Iraq.

Political alliances that span the Sunni-Shi'i divide persist, despite the U.S.-designed electoral system that rewards mobilization along sectarian lines. The legacy of the 1920 revolution points toward an Iraq that transcends external constraints and internal divisions, and emerges truly independent and united at last.

Want to Learn More?

Eli Amarilyo, "History, Memory and Commemoration: The Iraqi Revolution of 1920 and the Process of Nation Building in Iraq," Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 51, no. 1 (2015). An analysis of ideological legacy of the revolt.

Aylmar Haldane, The Insurrection in Mesopotamia, 1920 (London: Blackwood, 1922). The Classic account of British military operations.

Abbas Kadhim, Reclaiming Iraq: The 1920 Revolution and the Founding of the Modern State (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012). A recent synthesis that highlights neglected Shi'i participants.

Ian Rutledge, Enemy on the Euphrates (London: Saqi Books, 2014). A readable survey based on archival material.

Charles Tripp, A History of Iraq, third edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). A comprehensive, authoritative overview.

Amal Vinogradov, "The 1920 Revolt in Iraq Reconsidered: The Role of Tribes in National Politics," International Journal of Middle East Studies, vol. 3, no. 2 (1972). An early revision of accepted interpretations.